Genre

Ephesians exemplifies the genre of the NT epistle, with its salutation (including sender, recipients, and greeting), thanksgiving, exposition, exhortation, and closing (including final greetings and benediction). The main argument of the letter is punctuated by several prayers and an interior benediction (Eph. 3:20–21) that marks the transition from doctrinal affirmations to practical exhortations. Chapter 2 takes the form of a spiritual biography, in which Paul recounts the saving work of Christ in the life of every Christian, and especially in the lives of Gentiles who are now included in the one new people of God. In chapter 3 the apostle takes an autobiographical turn as he testifies about his calling to the Gentiles and his prayers for the Ephesian church. The paraenesis (series of moral exhortations) consists mainly of instructions for household conduct, both for the church as the household of faith and for individual believers in their domestic relationships. The famous description of the complete armor in the last chapter is an extended metaphor. Paul also catalogs the blessings of salvation in a lofty and exhilarating lyrical style.

Ephesians finds its central unity in the work of Jesus Christ and in the community of people (both Jews and Gentiles) who are corporately united in him. The strong opening statement of praise and the absence of any theological polemics make Ephesians pervasively positive in tone. The clear division of the epistle into two halves of nearly equal length (namely, the doctrinal section in chs. 1–3 and the practical section in chs. 4–6) also provides a strong sense of structural unity.

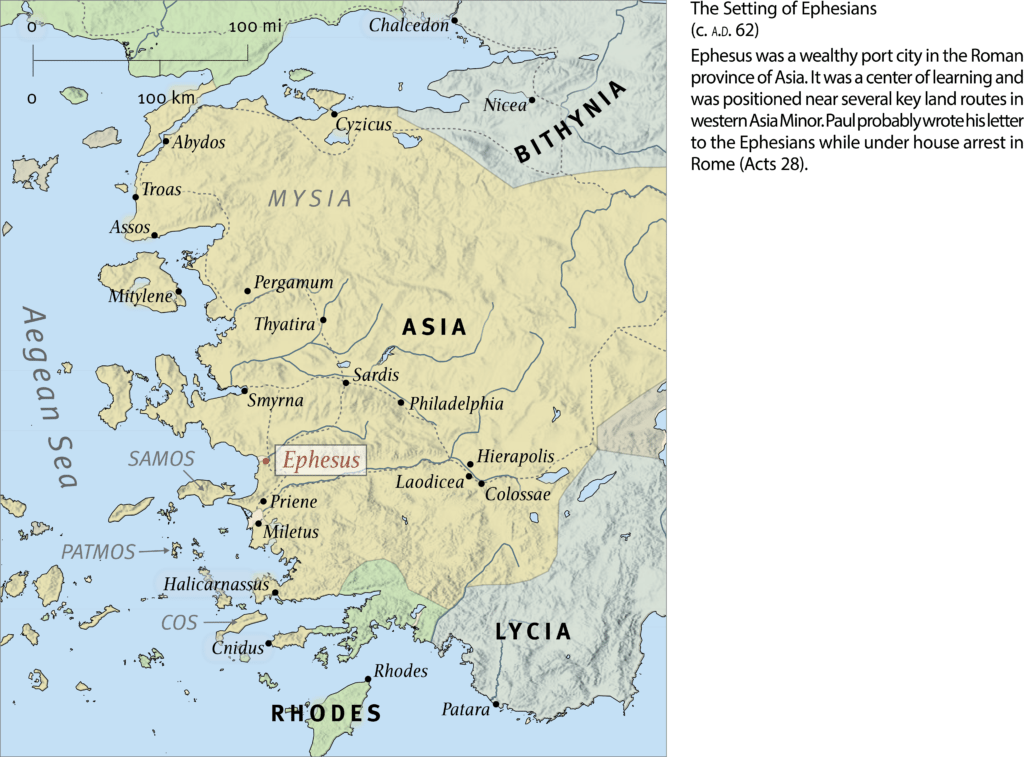

Setting

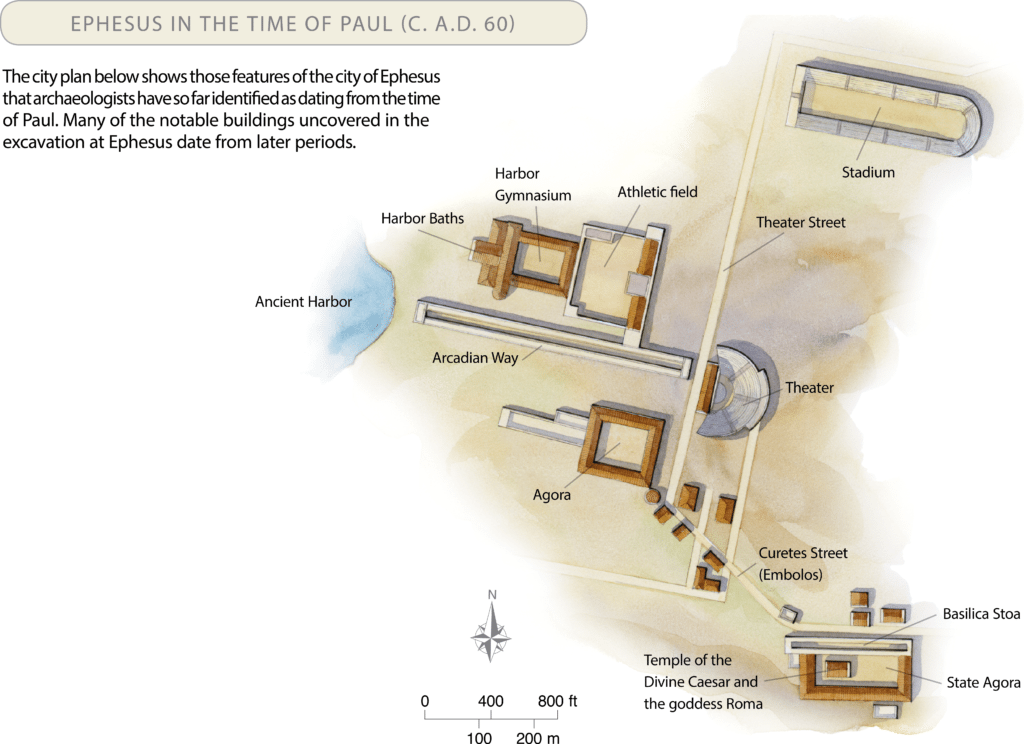

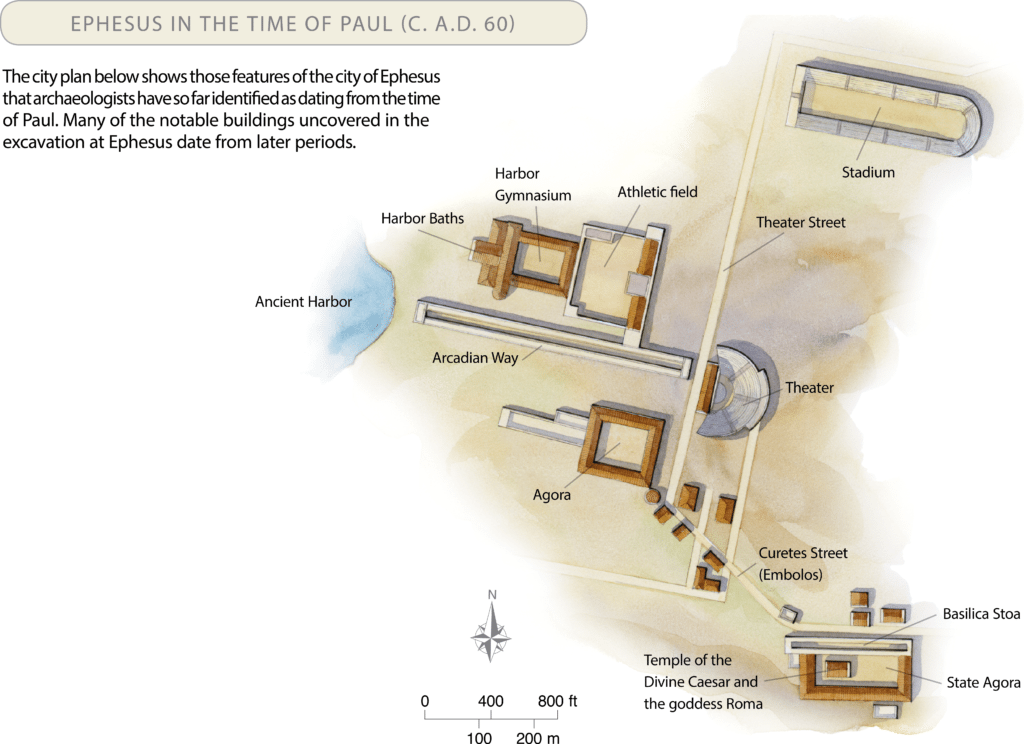

An important port city on the west coast of Asia, Ephesus boasted the temple of Artemis (one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world). Just a few decades before Paul, Strabo called Ephesus the greatest emporium in the province of Asia Minor (Geography 12.8.15; cf. 14.1.20–26). However, the silting up of the harbor and the ravages of earthquakes caused the abandonment of the harbor city several centuries later. Today, among the vast archaeological remains, some key structures date from the actual time of the NT.

The grandiose theater, where citizens chanted “great is Artemis of the Ephesians” (Acts 19:29–40), had been enlarged under Claudius near the time when Paul was in the city. It held an estimated 20,000 or more spectators. The theater looked west toward the port. From the theater a processional way led north toward the temple of Artemis. In the fourth century b.c. the Ephesians proudly rebuilt this huge temple with their own funds after a fire, even refusing aid from Alexander the Great. The temple surroundings were deemed an official “refuge” for those fearing vengeance, and they played a central part in the economic prosperity of the city, even acting at times like a bank. A eunuch priest served the goddess Artemis, assisted by virgin women. Today very little remains of that once great temple beyond its foundations and a sizable altar, although the nearby museum displays two large statues of Artemis discovered elsewhere in Ephesus.

Other archaeologically extant religious structures include a post-NT temple of Serapis and several important imperial cult temples. Before Paul’s day, Ephesus had proudly obtained the right to host the Temple of the Divine Julius [Caesar] and the goddess Roma. The city later housed memorials to the emperors Trajan (A.D. 98–117) and Hadrian (A.D. 117–138); and it possessed a huge temple of Domitian (A.D. 81–96), which may have been constructed during the time the apostle John was in western Asia. Luke testifies to Jewish presence in Ephesus (Acts 18:19, 24; 19:1–10, 13–17), and this is confirmed by inscriptions and by literary sources (e.g., Josephus, Against Apion 2.39; Jewish Antiquities 14.262–264).

Civic structures during the time of Paul included the state agora (marketplace) with its stoa, basilica, and town hall. This spilled out onto Curetes Street, which contained several monuments to important citizens such as Pollio and Memmius. Curetes Street led to the commercial agora neighboring the theater; this large market square could be entered through the Mazaeus and Mithradates Gate (erected in honor of their patrons Caesar Augustus and Marcus Agrippa). Shops lined this agora and part of Curetes Street. A building across the street from the agora has frequently been called a brothel, although some have questioned this. On the way to the Artemis temple from the theater, one would have passed the huge stadium renovated or built under Nero (A.D. 54–68).

The wealth of some residents of Ephesus is apparent in the lavish terrace houses just off Curetes Street. Later inscriptions mention a guild of silversmiths and even give the names of specific silversmiths (cf. Demetrius the silversmith, mentioned in Acts 19:24). However, as in most Roman cities, many people would have been in the servant class, and others would not have claimed much wealth. By the end of the second century (after the NT period) many other monumental structures were added, including some important gymnasia and the famous Library of Celsus. Remains of the giant Byzantine Church of Mary remind one that this former pagan town later hosted an important church council (the Council of Ephesus, A.D. 431).