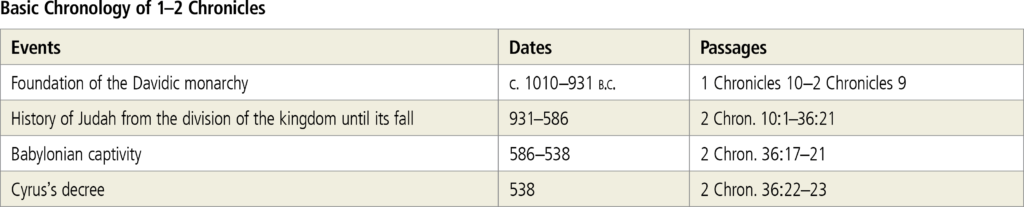

The Babylonian campaign against Judah, which began in 605 B.C. under Nebuchadnezzar, climaxed in the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple in 586 and the deportation of many of its leading people to settlements near Babylon. The conquest meant the overthrow of the Davidic monarchy and the end of Judah as a nation-state. Babylon, in turn, fell in 538 B.C. to the Persians under Cyrus II. The Persians followed a more benign policy of permitting the exiled people groups to return to their lands (now provinces in the Persian Empire) to rebuild their cities and reestablish their religious practices. Groups of exiles from Judah, including priests and civil leaders, returned in 538 B.C., but the temple was not completely rebuilt until 516. This initial restoration was followed by those who returned in 458 B.C. with Ezra, who came to reestablish the Law of Moses as the rule for the community’s life, and Nehemiah, who arrived as governor in 445 to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem.

Chronicles was most probably composed in this period, or some years afterward. Judah, as the historical heir of Israel, had been reconstituted in the land, with the temple rebuilt and functioning in Jerusalem. Yet it was a community much reduced in strength and numbers, occupying only a small portion of the land compared to the preexilic kingdom. The people of Judah were subject to foreign overlords, living in the midst of a mixed, and sometimes antagonistic, population. In many ways their conditions in the land were still characterized by exile rather than restoration (see Ezra 9:6–15; Neh. 9:32–36). The questions of Israel’s place in God’s purposes and the meaning of his ancient promises to David were pressing ones.

With such questions in mind, the Chronicler wrote to commend a positive prescription for the spiritual and social renewal of his community. He presented an interpretation of Israel’s past, drawing mainly on the books of Samuel and Kings. He recast and supplemented those books in many ways, not only to show how the nation’s unfaithfulness to God had led it into disaster but also to point out how its faithful kings and people had experienced God’s blessing. These episodes were evidently intended to encourage a similar response in the hearer. The exhortative character of Chronicles is pronounced, especially in the speeches of the kings and prophets. Those recorded speeches rhetorically address the people and priests of the Chronicler’s present, the historical heirs of preexilic Israel.

The Chronicler’s narrative method is clear and explicit. He recounts the history of Israel and the Davidic monarchy down to the exile primarily as a matter of “seeking God” or “forsaking him,” and sets out the consequences that flow from that choice for the king and people. To seek God means to orient one’s life toward him in active faith and obedience, to be diligent in fulfilling the commands of the Mosaic law, to oppose idolatry, and especially to support and participate in the authorized worship of the temple (see 1 Chron. 10:13; 13:3; 15:13; 16:10; 22:19; 28:9; 2 Chron. 1:5; 12:14; 14:4, 7; 15:2, 4; 16:12; 17:4; 18:4; 19:3; 20:4; 22:9; 26:5; 30:19; 31:21; 34:3). Those who seek God experience his blessing, typically in the form of large families (1 Chron. 14:3–7; 2 Chron. 11:19–21; 13:21; 24:3), building projects (1 Chron. 14:1; 2 Chron. 8:1–6; 11:5–12; 14:6–7; 17:12; 26:2, 6; 27:3–4; 32:5, 29–30; 33:14), riches and honor (1 Chron. 14:2, 17; 29:2–5; 2 Chron. 9:13–14, 22; 26:8, 15), military strength and success (1 Chron. 5:20–22; 14:8–16; 18:1–20:8; 2 Chron. 8:3; 13:13–18; 14:9–15; 20:20–26; 25:11–13; 26:4–8; 27:5–7; 32:20–22), and peace for the land (1 Chron. 22:18; 23:25; 2 Chron. 14:4–7; 15:15, 19; 17:10).

The converse is to forsake God, which includes apostasy and idolatry, the neglect and abuse of the temple and its institutions, despising the word of prophets, and egregious violence (see 1 Chron. 28:9; 2 Chron. 12:1, 5; 13:10; 21:10; 24:18). God’s punishment for forsaking him and his law includes defeat and despoiling by foreign enemies (1 Chron. 10:1–7; 2 Chron. 12:2–4; 21:8–11, 16–17; 24:23–24; 25:17–24; 28:5–8, 16–21; 33:10–11; 35:20–24; 36:5–19), sickness and death for disobedient individuals (1 Chron. 2:3; 10:13–14; 2 Chron. 16:12; 21:12–15, 18–19; 22:7–9; 23:14–15; 24:25; 25:27; 26:16–21; 33:24; 35:23–24), and, finally, forfeiture of the land and exile for the people (1 Chron. 5:26; 9:1; 2 Chron. 36:18, 20). The basic concepts represented by “seeking God” or “forsaking” him are, of course, also expressed by a broader range of phrases (“to serve God with a whole heart”; “to do what is right [or evil] in the eyes of the Lord”; and esp. “to be unfaithful”; see ESV Study Bible note on 1 Chron. 2:3–8).

Just as important as the exhortation to faithful seeking, if not more so, is the message of forgiveness and restoration to God through sacrifices of atonement and humble prayer. The Chronicler is insistent that from beginning (1 Chron. 2:3, 7) to end (2 Chron. 36:14), Israel is a sinful people that fails to reverence God in his holiness as they should. That sinfulness extends even to David (1 Chron. 21:1), who best exemplifies for the Chronicler what it means to seek God. Yet God in his mercy provides the way back to himself. The temple stands where David repented and offered sacrifice. It is designated by God as the instrument of his forgiveness and the point at which the consequences of sin may be reversed (2 Chron. 7:12–16). This emphasis on repentance explains one of the notable differences in presentation and purpose between Chronicles and Kings. The Chronicler would certainly agree with the writer(s) of Kings that figures such as Rehoboam and Manasseh were notorious sinners whose disobedience divided the kingdom and led to its fall. But the Chronicler also uses them as examples of repentance and personal recipients of God’s grace.

The destruction of the kingdom of Judah and the exile of its people are duly explained as the consequence of Israel’s persistent unfaithfulness and its rejection of the prophetic summons to repentance (2 Chron. 36:16). But the ending of Chronicles—Cyrus’s decree to return and rebuild the temple (2 Chron. 36:22–23)—takes the reader full circle to the beginning: a representative core of God’s people has once again been gathered to the land and to the temple in Jerusalem, their daily round of worship standing in continuity with the preexilic days (1 Chron. 9:2–34). The Chronicler has shown how Israel’s fall occurred, how such a disaster may be avoided in the future, and how all who belong to Israel may be gathered and consolidated as God’s people. At the center stands the temple, the symbol of Yahweh’s constant will to forgive and restore his penitent people who “seek his face” in prayer (2 Chron. 7:14). The restored temple testifies to the permanent continuance of God’s covenant promises to David. Holding fast to those promises, and supporting the temple institutions that testify to them, is Israel’s road to greater blessing and restoration.

A key question in discerning the Chronicler’s purpose has to do with the promise to David of a permanent dynasty (1 Chron. 17:12–14; 2 Chron. 6:16–17; 13:5) in an age when the Davidic monarchy had long since ceased to function. Some commentators believe that the Chronicler envisioned a return to something like the preexilic kingdom, with a descendant of David once more enthroned in Jerusalem. Yet nothing in the book allows it to be tied so directly to the political circumstances of postexilic Judah. Alternatively, it has been argued that the Chronicler saw the temple and its priestly institutions as the heir to these promises, replacing the defunct monarchy in the theocratic rule of the religious community. Against this is the fact that the Chronicler goes to great lengths to show that the monarchy and the temple are separate pillars of God’s rule in Israel, and that the Davidic house has been preserved through great danger (see 2 Chronicles 21–23, esp. 2 Chron. 23:3) and down into the Chronicler’s day (1 Chron. 3:17–24). Moreover, the Davidic dynasty is connected with God’s own throne and eternal kingdom as the instrument of God’s rule over Israel (1 Chron. 28:5; 2 Chron. 9:8) and therefore has a transcendent character compared to “the kingdoms of the countries” (1 Chron. 29:30). For these reasons, it seems clear that the Chronicler understood the Davidic line to be a focus of hope for the future, although he has not specified what this hope entails. This can be called an implicit messianism, a hope that will bear fruit in the appearance of Christ. The Chronicler’s eye, however, is directed more to what his own community may become in the interim: he envisions “all Israel” (not only Judah but all the tribes) as once more possessing the land, living according to the Law of Moses, and worshiping at the temple.