The first time Shurlyn Williams left her abusive boyfriend, she didn’t go far enough.

“I was still around,” she said. “And I had our daughter. I was like, ‘I’m not going to talk to him anymore,’ but he’s a good dad.”

She gave him another shot, but about four months ago, he hurt her again. This time, she took her three children (ages 3, 1, and 8 months) and moved about 30 minutes away.

She didn’t do it alone. Williams was connected with Better Together, an organization that provides crisis care for children before foster care is needed.

But along the way, Better Together staff wondered if they could get to families even sooner.

“We found families were hurting because of spiritual and material poverty,” director of strategic development Leah Hughey said. “From the beginning, our focus has been on working with churches to create solutions to messy social problems that many people have written off as unsolvable.”

After all, “Jesus doesn’t look at any problem and say, ‘Well, that’s a pickle,’” she said. “He says to obstacles, ‘Get out of my way.’ . . . What if Jesus looked at poverty and said, ‘Church, go take that hill’?”

Better Together wanted to give it a shot. Looking for a way to connect large numbers of people with employment, they figured they’d try a job fair. But they’d hold it at a church.

“It was a spaghetti-against-the-wall idea,” Hughey said.

It stuck. When the first one in 2016 went well—and then the second—news began to spread. In the past two years, Better Together has hosted more than 60 job fairs, all with local churches. More than 13,000 people have come looking for employment.

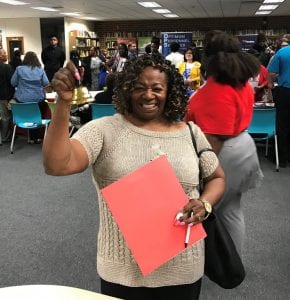

One of them was Williams, who was offered positions at Jimmy John’s, Wendy’s, and La Solera restaurants. She picked Jimmy John’s because it was down the street from her new place. Two months in, she was promoted to assistant manager. Now she’s saving for a car—“I’m working very hard to get to where I need to be.”

“The most encouraging thing I’ve ever done in ministry—in terms of my own soul—has been to preach the gospel in the Middle East,” said pastor and TGC Council member Thabiti Anyabwile, whose Anacostia River Church hosted a Better Together job fair last May. “A close second was the job fair. It was one of the most life-giving things I’ve had the privilege to be able to do, in part because of the hope that was transferred and shared in the sense of measurable differences in people’s lives.”

Moving Upstream

Jay Harris pastors The Ville Church in Jacksonville, Florida. The church sits in an area that leads the city in poverty, unemployment, infant deaths, and homicide.

“Economically, it’s hard,” Harris said. “You can’t get anywhere, and there are no jobs. . . . It’s hard to proclaim Jesus and look past these things.”

In Anyabwile’s Anacostia neighborhood in Washington, D.C., a third of people live in poverty. The median household income is a little more than $24,000; nearly half of the children live in poverty (49 percent). Around 13 percent of people there were unemployed in 2017, nearly three-times that of the rest of the country (between 4 percent and 5 percent in 2017).

Our focus has been on working with churches to create solutions to messy social problems that many people have written off as unsolvable.

“In poor, inner-city neighborhoods, jobs aren’t located where the people live, so most of our folk are looking for vanishing entry-level work,” Anyabwile said. “That entry-level work has long moved out to suburbs and other places where if you don’t have transportation, you’re spending two hours on a bus to get to work. Add in kids and a household, and it’s a tremendously demanding life.”

If you take seriously the Bible’s injunction that if a man doesn’t work, he doesn’t eat (2 Thess. 3:10), or that if a person doesn’t provide for his household, he has denied the faith (1 Tim. 5:8), then “employment ought to be high up the list of ministry responsibilities for people in the local church,” Anyabwile said.

He preaches about it. And he sees churches offering food pantries, helping with utility or rent bills, and providing cars to those who don’t have one.

That type of benevolence is “80 percent to 90 percent of what churches do,” he said. “It’s not wrong, but it’s downstream. Gainful employment changes all of those things. If people are working, they are enjoying the dignity of work. If they’re earning a competitive income, they’re able to take care of food and clothing and housing needs. Some of our effort needs to be back upstream.”

Handing Out Hope

The Ville is a relatively new church (planted in 2012), with about 90 regularly attending adults.

“As our church membership grows with the people from the community, financial sustainability is a struggle,” Harris said. The church lives from tithe check to tithe check, selling clothing online to bring in extra income.

So when Hughey told Harris about Better Together’s job fair, he was all in. It was a way to help the community without the financial outlay of starting a food pantry or a car program.

“We have participated in three so far,” Harris told TGC. Better Together is “breathing life into these people’s lives. For me, it’s a dream come true.”

Because it’s not just a hand up for the unemployed. It’s also a tangible way for the church to stretch out.

The local church is the location and anchor for Better Together’s job fairs. (Sometimes a couple churches do one together at a community center or one of their buildings.) While Better Together works behind the scenes to gather employers, the church is responsible for passing out fliers and putting up posters to alert the community.

“We combined it with our regular door-to-door evangelism work,” Anyabwile said. “When we first extended the leaflet, the response was stiffness and ‘I don’t want what you’re selling.’ Then we said, ‘Hey, we’re having a job fair,’ and the person’s whole countenance would change.”

“Job fair?” they’d ask him. “Where is it? When is it? Can I get two of those?”

“The sense of hope was palpable,” Anyabwile said. “Some people would say, ‘I’m a returning citizen. I have a record. Can I come?’”

When he told them “we have employers who hire people with a background,” their faces “would light up. . . . I’ve never done anything in the community that triggered so much hope and optimism as this job fair.”

After doing it a few times, The Ville has an email list of participants it can alert, asking them to come and bring any family or friends who need jobs.

“Over 450 people came” to the last one, Harris said. “We had a line around the block.”

How to Hold a Gospel-Centered Job Fair

“Even employers were like, ‘This is the most humane job fair I’ve ever experienced,’” Anyabwile said. They told him, “We’ve never had as many job seekers do basic things like shake my hand firmly or look me in the eye while they talked to me.”

That wasn’t an accident. On the way in, Better Together takes job seekers through stations where pastors welcome and pray for them. Volunteer church members teach them a few interviewing skills. And more volunteers offer to coach them through the experience.

It’s not just a hand up for the unemployed. It’s also a tangible way for the church to stretch out.

Better Together teaches volunteers to gauge ability and interest, perhaps through conversations such as, “Here’s the list of companies here today. Have you heard of any of them before? Oh, you have a cell phone with Verizon? Do you like to talk on the phone? Do you think you might like to be a customer service person for Verizon?”

Volunteers can also help entertain young children while mothers interview. They can give feedback on what a job seeker can do differently in the next interview. They can help job seekers explain a felony conviction. (Be honest about the past and hopeful about the future: “I’m ready to work hard and jump onto a new path in life.”)

Some job seekers need more help than others. One “serial job coach” comes to every job fair and only helps about three people all day. “He gets to know them, he gives them his cell number, and he keeps in touch with them,” Hughey said. “He tells them, ‘I go to church here. I sit in this row. Come with me on Sunday.’”

On the Spot

Better Together also works with employers. At first, some would just send a person to stand by a booth and hand out a flier with the company website on it.

“It’s been a slow process,” Hughey said. “But we have moved employers to be more of a one-stop campaign. We keep urging them to take one more step in the hiring process than they did last time.”

That means sending a manager who can actually make hiring decisions. It means adding computers so online applications can be filled out right there. (One church had a computer lab on site; it worked so well for online apps that Better Together tries to bring computer labs to each location.)

Better Together likes it best when companies make job offers on the spot. “This was significant for us,” Hughey said. “In cities with transportation constraints, it can be expensive to come here for fingerprinting, and here for this interview, and here to pick up a Social Security card, and then back here. It’s incredible how many hours it takes someone in poverty to take one of those trips.”

On-the-spot job offers also give the whole room something to celebrate.

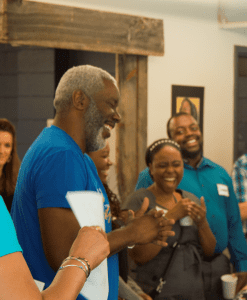

“We have a simple bell—the first one I bought was a Santa bell on clearance at Party City,” Hughey said. “We put it on a stand, somewhere visible. Then when you get a job offer, you ring the bell.”

Hughey has seen people come in moving slowly and not making eye contact who later ring the bell with “tears streaming down their cheeks. . . . The whole room stops—even if they’re in the middle of an interview—and clap and cheer and whistle like it was a touchdown at the Super Bowl.”

Justine Wilk is a director of operations for Premier Kings, a large Burger King franchisee in the Southeast.

“This was the first time I’d ever really participated in a community job fair,” she said. “I tried to have job fairs at the business and hadn’t gotten anybody to show up. For me, this was really eye-opening. It really is a community effort. This organization isn’t doing it for the businesses, but for the community. That’s the difference.”

Wilk has been to “at least eight” Better Together job fair in the Jacksonville area. She’s hired around 25 managers and around 40 staff employees.

Some employees she’s been able to depend on and promote; others she’s had to let go. Overall, though, Better Together job seekers “stay longer and come in with a better attitude,” she said. Maybe that’s because they were already motivated—after all, they cared enough to go to a job fair. Or maybe it’s because Better Together tries to give as much help as it can, even after the fair.

Social Services

Better Together staff like to fill up their job fairs with people from the church—pastors who hang around the “opportunity bell” to hear stories, 80-year-old ladies who come to pray in front of the wall covered in post-it-note prayer requests, and those volunteer coaches. The hope is to introduce job seekers to people who want to love them, help them, and introduce them to the gospel.

Some job seekers are already involved with Better Together’s family services arm. For example, Williams’s daughter was hosted by a Better Together family during her first domestic-violence incident. Afterward, case coordinator Selena Hinsdale kept in close touch, helping her find a home to rent and tugging her along to the job fair. (“I can’t get rid of her,” Williams laughs.)

Better Together would like to help more people in that type of situation. As Wilk noticed, not everyone is ready for a job. Some need childcare. Some need transportation. And some need training on how to dress and how to interact with customers and how to show up on time every day.

“We experimented with having a job club for six to eight weeks after job fairs to catch people who got a job and need retention training,” Hughey said. “We also wanted to keep supporting those who didn’t, so they didn’t feel demoralized. But we have not had the interest from job seekers we would have expected.”

So Better Together focuses on including booths for local organizations—the food pantry, the homeless shelter, the pro bono legal counseling, the pregnancy center. Eventually, they’d like to strengthen the hosting church’s ties with local nonprofits as a way to tighten the support around each job seeker.

“The needs in an underserved community are always spiritual and physical—they’re multifaceted,” Hughey said. “Mom and Dad and Junior and Grandma all need something. It’s different and messy. For us to say, ‘All you need is a job, young man,’ is missing all that.

Reclaiming Work

“Work was created before the fall,” Hughey said. “There’s something intrinsically good about it. We were created in the image of a God who works.”

The goodness of work—even if it isn’t your “passion”—is borne out in statistics. People who are chronically unemployed are more likely to abuse substances, become depressed, and commit domestic violence.

There is also inherent goodness in bringing together two different populations.

“Every time I’m at a job fair, I see employers from the suburbs talking to girls with babies on their hips and young men with teardrop tattoos,” Hughey said. “I think of how foolish it was in the days of Jesus when people said that nothing good could come out of Nazareth, because the Savior of the universe did.”

Today, “there’s almost a theology of reclaiming what is holy” in these job fairs, she said. “There isn’t an inch of this planet God didn’t create and call good—not an inch that doesn’t cry out for Christ’s return, that’s not going to be fully restored in eternity. And so Brentwood and Jacksonville are going to be restored. Anacostia is going to be restored. That process is happening right now, because we live on the other side of the cross.”

Doing restoration work is like watching “an atomic bomb of hope going off in the community,” she said. “The church is saying out loud, ‘Jesus loves this place.’”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.