Twenty-seven-year-old Saolomon Mouacheupao grew up in a family that went to church. But after he came to faith as a high school sophomore, his first impulse was to stop attending.

“I felt disenfranchised with church,” he said. “It didn’t really do much for me. . . . When I got saved in my bedroom, I started reading these books and started listening to these sermons on my own. And for the first month and a half, I remember being like, ‘I don’t ever need to go to church again. I have learned more about the Bible by myself here than I ever have my whole life.’”

Mouacheupao was listening to pastors like David Platt, Matt Chandler, Francis Chan, and Mark Driscoll. But soon, the pastors he was listening to by himself convinced him that he needed to be with other Christians.

“Pretty immediately, I started serving in my local church—I went to a real small church, of about 125 people,” he said. “My youth group was like 20 kids. My youth pastor gave me opportunities to lead small groups. I even got to teach a couple of times. I taught kids Sunday school, fell in love with serving, and almost immediately started asking myself if God wanted me to be a pastor.”

Mouacheupao’s return to church mirrors a larger trend in his generation. From England to Norway to the United States, more young people—especially men—are making a personal commitment to Jesus and attending worship services. This fall, MDiv enrollment at seminaries was up “for the first time in many years,” according to the Association of Theological Schools (ATS).

Mouacheupao is one of those students, the first wave of Gen-Z pastors to enter ministry. They’re proving to be a more complicated generation than their parents—the relatively pragmatic and self-reliant Gen X.

In general, today’s young church leaders are unusually well-informed and excellent researchers, according to their mentors and teachers. But they also have fragmented attention and weaker reading and writing skills. They want the deep roots and accountability of denominations, but they’re also skeptical of authority. And while they’re eager to be influencers, they have less confidence than other generations did at their age.

“The majority of Gen Z has some major issues,” said Jake Baur, a 26-year-old intern at Capitol Hill Baptist Church. “But those who are aware of the problems are shining. There’s a wide pool of thoughtful people who love the Scriptures and are aware of the world’s agenda, the anxieties of our generation, and the dangers of social media and phones. They’re doing everything they can to follow the Lord and his ways. We have a lot of people coming out of our generation who are really going to cling to God’s Word and love others.”

Why Are You the Way That You Are?

A decade or two ago, the pastors Mouacheupao found online were the young part of the Young, Restless, and Reformed movement. As they discovered historical Reformed theology, they enthusiastically explained it in their churches, books, and conferences.

These men, who were among the last members of Gen X and the first of the millennials, “worked their tails off, no matter what,” said Blair Waggett, director of pastoral internships, apprenticeships, and residencies at the Summit Church in Durham, North Carolina.

They had to, because another hallmark of ministry in the early 2000s was doing hard things and going to hard places. This was the cohort rushing to plant churches (one of the hardest jobs in ministry) in city centers (one of the hardest places for evangelism).

After a while, the generational vibe shifted. When the “least-parented, latchkey” Gen X got married, they had smaller families and were more involved parents. Their kids, primarily Gen Zers, were the first to grow up with smartphones and social media. Their experiences, socializing, and education were increasingly monitored or digital.

As a result, the bottom end of the millennials and top end of Gen Z were slower to drive, date, or work than previous generations of teenagers, psychology researcher Jean Twenge found. “The developmental trajectory of adolescence has slowed, with teens growing up more slowly than they used to,” she said.

As this group entered young adulthood, the trend continued—they were slower to get married, have children, and buy houses than previous generations at their age. In 2025, only 6 percent of Gen Z employees were aiming for a leadership position at work. Nearly 40 percent of young workers weren’t interested in being promoted at all.

The same shift could be seen at church. While enrollment at evangelical seminaries didn’t exactly dip, the number of students aiming at MDivs—the degree most preaching pastors get—began to drop in 2017.

“I had a lot of friends who wanted to go into counseling,” said Mouacheupao, who was at Moody Bible Institute from 2017 to 2020. “I think there was a fear of having authority, or of being perceived as wanting authority.” (When he was a junior, three of his friends staged an intervention, worried that his complementarian views were going to hurt future congregants.)

That trend reflects the culture, in which male authority figures, from bosses to police officers to politicians, have often been seen as toxic. It also likely stems from COVID-19, which increased mental health issues and highlighted the difficulty of pastoral work.

“Anxiety is definitely another reason [for fewer pastoral students],” Baur said. “You get told how hard pastoring is. And we’re a generation that’s just constantly lacking self-confidence.”

But lately, the vibe has begun to shift again.

“I’m still involved at Moody, and it seems like there’s been an uptick of guys who want to enter into pastoral ministry, even from the time I was there five years ago,” Mouacheupao said.

He’s right. In November, the ATS reported that for the second consecutive year, more of its schools had grown than declined.

“This is an interesting development,” wrote ATS senior director and COO Chris Meinzer. “Overall MDiv enrollment is up, and the growth is widespread.”

More than half of schools—including 58 percent of evangelical schools—reported increases in MDiv enrollment.

So who are these students?

Spiritually Serious but Scattered

When I asked older leaders to describe Gen Z, they all began with the same observation.

“Gen Z leaders floor me [with] how spiritually deep they are,” Waggett said. “They’re tenacious about getting after it in their spiritual walk. Does that create a completely infallible leader? No. But it does create a leader that is deeply connected to the body of Christ and the work of Jesus. It’s so exciting.”

At Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS) in Jackson, dean of students Charlie Wingard is equally enthusiastic.

“When I take them as a whole, they are spiritually mature,” he said. “They’re very earnest. They want to learn about ministry, and they want to serve the Lord faithfully. I’m also an assistant pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Jackson, and I know the Sunday school classes for the Gen Z age group are full—and they’re full of young men and women who are serious about Christian discipleship. They want to form solid Christian families. Many of them are at both morning and evening services.”

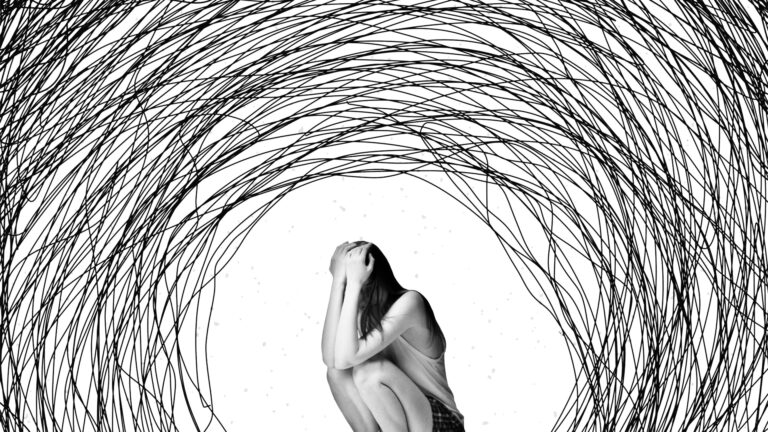

The desire for spiritual depth and disciplines is a natural reaction of an “overstimulated, underformed, undertraditioned generation that is in need of anchoring to something more than the immediate moment,” said 28-year-old Lakelight Institute associate director Glenn Wishnew. “Gen Z often feels addicted to their phones and purposeless or aimless in their daily lives.”

Their screen-shortened attention span makes prayer, Bible reading, and paying attention in church more difficult, he said. But those practices are also their lifeline out of the chaotic, ever-changing, infinite scroll.

Gen Z’s serious Christianity is also a result of having instant access to the most and best theology that humanity has produced.

At University Reformed Church in Lansing, Michigan, pastor Jason Helopoulos noticed the men in his ministry training program love prayer, expository preaching, and the local church.

“They’re also very concerned about what I’d call experimental religion or experiential Christianity,” he said. “They understand you have to have sound doctrine—that’s not lost on this generation. Maybe because they’ve seen too many hucksters.”

Skeptical of Authority but Longing for Connection and Accountability

Gen Z doesn’t wonder long about most things: Is this an orthodox view of blessing? Is that a real Charles Spurgeon quote? Did the Bible really say that?

“One of the beautiful things about Gen Z is they’re pushing me to be sharp,” Waggett said. “I have to have the newest, most thoughtful thing—cause they’re ChatGPTing me while I’m teaching them.”

Waggett’s students fact-check him in real time, instantly catching when he misquotes someone, misstates a fact, or misses an analogy. Their access to information means they’re quickly able to spot a fake. But it’s also a liability.

“My generation has no concept of good biblical authority,” Baur said. “Any concept we have of authority is negative. I see in people my own age, and in my youth group students, that there’s not any trust for your pastor until he proves himself trustworthy. There’s probably not any trust for the Word of God until it proves itself trustworthy. And there’s a disposition of skepticism toward any truth claim until it can be defended.”

That mistrust has been exacerbated by the extensive media coverage of public figures’ misdeeds.

“In some sense, the church has said, ‘We don’t ever want to be like those people who were mean and cruel with their authority, so we’ll just be nice to everyone,’” Baur said. “But that taught people the church doesn’t have authority in their lives, and church authority is not only a good thing but a biblical thing. If we’re constantly doubting the church has authority in our lives, we’re never going to allow it to shape or transform us in the ways it could.”

Baur struggles with this distrust himself, especially when it comes to institutions like denominations.

“I don’t think I’ll end up as part of a formal denomination,” he said. That’s partially because he’s seen liberal leaders pull mainline denominations further left than their more conservative laity likely wanted to go.

But he also sees the value in a denomination’s ability to provide accountability, community, and deep historical roots. That’s attractive to a lot of Gen Z—see the growing popularity of high-church, liturgical traditions.

“When I was at Moody, there was a trend toward becoming Anglican or Catholic or Eastern Orthodox,” Mouacheupao said. “That’s still true now. I have a pastoral intern who’s at Moody right now, and a lot of his floor is Anglican.”

Highly Structured but Keeping All Options Open

Part of the draw of highly liturgical traditions is that Gen Z is “tired of making stuff up on [their] own,” Mouacheupao said.

Gen Z has been given more choices—from their coffee flavor to their gender—than any previous generation. But they’re also growing up with more parent-arranged playdates, coach-arranged activity schedules, and standardized test–arranged academic curricula.

“When I was growing up, I had very little in the way of adult supervision on almost anything I did outside of school,” said Wingard, who was born in 1957. When he played ball on a playground, there wasn’t an adult in sight. During long weekends or spring break, Wingard and his high school friends often headed on camping trips, always without grown-ups.

“There were so many things I recall doing without the supervision of adults,” he said. That gave him confidence—as he watched his dad pastor a church and thought about going into ministry himself, he wasn’t “intimidated about having to figure out on the fly how to do the work of ministry.”

He also didn’t have to figure out which denomination he’d join—he’d be a Presbyterian, like his dad.

It’s different now. Baur grew up in an Evangelical Free church, is doing an internship at a Southern Baptist church, and will probably enroll at the predominantly Presbyterian RTS.

At the same time, young men are looking for a structured way to step from school to the pulpit. In the last 10 years, Summit, University Reformed, and a host of other churches have launched ministry training programs to supplement seminary education.

Interest in the programs “has really increased,” Helopoulos said. “It’s a late-bloomer generation. There’s a maturation process that just seems to take a little longer. More than anything, there’s a lack of confidence I haven’t seen in previous generations.”

Insecure but Wanting to Influence

One benefit of an internship or residency is that it gives young men a chance to build their confidence by doing real-life ministry, Helopoulos said.

“We want to give them real opportunities to test their gifts and to say, ‘The Lord can work through me and is working through me,’” he said. “They need a stable church where they can fail a little bit and be encouraged, pick the ball right back up, and go after it again.”

This is important for a generation that has been trained, through experiences like the pandemic and cancel culture, not to take risks. “We are not bold,” Wishnew said.

Internships offer a slower way to step into ministry that’s both structured and offline.

“Some seminarians get the impression that the lasting influence they’re going to have in the churches they serve is through podcasts or social media,” Wingard said. “Some students think this is a place they need to invest their time. I tell them over and over that it takes you away from face-to-face interactions with people.”

The theological debates happening online aren’t productive for most people, he said. “I’m not sure the average pastor can accomplish much through it.”

Helopoulos agrees.

“You can start a podcast or a social media account, and you can say all kinds of inflammatory things, and you can get all kinds of followers,” he said. “But the reality is, those drift away if you don’t keep up that kind of mantra.”

Not only that, but the confidence gained by dunking on someone online is fleeting and hollow.

“There’s a real benefit to going through processes and institutions that, over time, engender right confidence,” he said. “Not hubris, but a right confidence of what you’ve been called to—confidence that you have some ability to serve the church well.”

Gen Z: More Addicted to—but Fighting Harder Against—Distraction and Pornography

Confidence isn’t the only thing Gen Z is losing to their phones.

“The average 20-year-old right now is absolutely addicted to their phone and addicted to social media,” Baur said. “We have not proven ourselves able to handle phones at all.”

This shows up in almost everything, from academics to entertainment.

“Many of them come out of academic environments where they’ve not been required to read and write as much as we would like,” Wingard said. To help, RTS has introduced writing labs.

“Another challenge they face—and we all face—is distraction,” he said. “Students come to me and say, ‘I don’t know if I can stay in seminary. I’m studying eight hours a day and going to class. I just don’t know if I can hang on.’ And my first response is always, ‘Let’s talk about that eight hours. Have you put your phone away? Are you trying to deal with text messages and emails and other notifications? Are you checking sports scores or looking at news feeds?’”

They are.

He tells them, “You’re not studying eight hours a day. Every time you break your concentration, you have to take time to get back on subject. Turn off the alerts on your computer. Consider even working with a pad and pencil if you must. And when you get home, concentrate on your spouse and children. Put away your computer. When you relax by watching a football game or a movie, don’t carry your phone with you. Enjoy the moment, truly relax, and then come back to your studies refreshed.”

And put your phone away when you’re doing ministry.

“We have had a couple of different guys where we’ve had to say to them, ‘When you are in a meeting, or when you’re with the staff, or you’re sitting in and listening to the session, your phone needs to be put away,’” Helopoulos said. “That’s a temptation for all of us—something we all have to work on. This is one of the things that can greatly affect your ministry. If the person before you doesn’t feel like they have your attention—that is one of the quickest ways to undo ministry effectiveness.”

Another way to hamstring your ministry is to outsource your thinking to AI.

“AI doesn’t merely give you answers, but also the way by which you get the answers,” Baur said. “You can ask it a very abstract, deep question and get both an answer and an argument. We were struggling with argumentative thinking before AI. It’s not going to be helpful to have something thinking for us.”

It’s tricky, because the better AI gets, the easier it’ll be to hide that you’re using it to do your work. At RTS, Wingard prefers to give some of his exams on paper.

“Sin always wants to be hidden,” Baur said. An easy place to hide it is in your pocket.

That’s one reason pornography use has skyrocketed, he said.

“Porn is so ubiquitous now in the lives of young men that it’s almost assumed they’ve had some history with it,” Helopoulos said. “In the Presbyterian ordination process, each presbytery examines candidates. We’ve made it a requirement to ask, ‘Are you using porn? Do you have a history of using porn?’ And in the last number of years, we’ve found that wasn’t sufficient.”

Now they ask, “What type of porn have you been observing?”

Answers can range from none to violent porn to bestiality, he said.

“Sin always wants more, and keeps digging you deeper and deeper unless it’s mortified, unless it’s killed,” he said. “It’s jettisoned by the grace of Christ. We’re not just fighting porn, but all the deeds of darkness and our Adversary’s desire to derail us and turn us away from the goodness and glory of Christ.”

Gen-Z Christians know that.

“This generation, from what I see, is fighting porn harder than anybody else,” Waggett said. “They’ll tell you what they’re doing. They want humility and accountability and a deeply spiritually formed life. So at the same time they have the most monumental struggle not to get into porn, they’re also monumentally struggling to fight it.”

Thinking Faster and Working Slower

While Gen Z’s attention is racing from one thing to the next, making them feel busy, their outward pace of life is slower. This shows up in later marriage and childbearing but also in other areas.

“They’ve really resided in this idea of rest and Sabbath,” Waggett said. “Sometimes I have to say to them, ‘Yes, but from our rest, we work—because we are designed for it, and because it’s a response to the gospel.’”

Sometimes that desire for rest or work boundaries can come across as laziness, Waggett said.

“But 9 times out of 10, what we perceive as laziness is just a misunderstanding of what is needed,” he said. “They’re not lazy. They’re coming from a generation that had a really challenging situation with COVID-19, and that wasn’t taught all the necessary soft skills and leadership mentality that comes with ministry.”

Wishnew is a little more direct about his own generation: “An idol of psychological comfort and safety is threaded through secular and Christian Gen-Z folks. Work-life balance, suspicion of corrupted institutions, life under COVID-19—all that falls under the safety rubric, in my opinion.”

The best thing to do is to talk with Gen Z, model good leadership, and walk with them as they learn, Waggett said. “Help them become who we know God has designed them to be.”

Future Is Bright

Gen Z is a study in contrasts—they’re used to unprecedented choices but also unprecedented structure. They’re exposed to more porn but are fighting it harder. They have more knowledge but are less skilled at offline communication.

Despite the incongruity, Wingard said, “I have a very optimistic view about what’s going to take place in the coming years. We are getting outstanding students. I listen to students in the preaching lab, and almost every week, from every student, I hear earnest expositions of God’s Word. I am listening to people who have wrestled with the text. One of the things that gives me a sense of anticipation of what’s going to take place in the future in our churches is the quality of the sermons I’m hearing in seminary.”

And maybe this generation—moving slower, fighting sin, desiring depth—is a perfect fit to pastor, teach Sunday school, or lead a youth group for those coming behind them.

“When I was doing youth ministry, I saw so much hunger in those kids for going deeper in the faith,” Baur said. “The constant complaint of students I ministered to was ‘We have deeper questions than we feel like are being answered right now.’”

Gen Z can do that, Waggett said.

“Gen Z leaders deeply desire authenticity,” he said. “They want community. They want feedback. They’re unbelievable. When we teach them about walking with integrity and humility, walking in open honesty with a community—Gen Z wants that anyway. It’s almost a layup in that respect.”

And increasingly, they’re getting ready to take responsibility. Sometime after Mouacheupao finishes his MDiv at Southern, he hopes to take a lead pastor role.

“I believe in the church,” he said. “I love the church. God wants to save lost people. Jesus is going to build his church. Those are all the things that drive me, the reasons that I get excited.”

Free eBook by Tim Keller: ‘The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness’

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

In Tim Keller’s short ebook, The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path To True Christian Joy, he explains how to overcome the toxic tendencies of our age一not by diluting biblical truth or denying our differences一but by rooting our identity in Christ.

TGC is offering this Keller resource for free, so you can discover the “blessed rest” that only self-forgetfulness brings.