“I will be your God, and you will be my people.”

This divine statement tells the story of the whole Bible and expresses the heart of God’s covenant with us. In this relationship God calls us to be committed to righteousness in every area of life: “Be holy, for I am holy” (Lev. 11:44).

Righteousness is a relational, covenantal term. It means to do right by the other party in the covenant. God always does what is right, and therefore we—those saved and set apart to him—should also always do what is right. Unrighteousness, on the other hand, is simply a failure to do what is right.

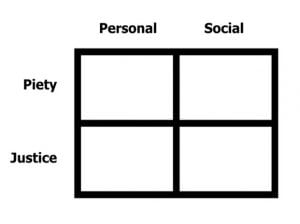

Window of Righteousness

Righteousness has four dimensions:

- Piety. Doing what is right according to God in a narrow sense that involves devotion and ceremony: “Live . . . in the flesh no longer for human passions but for the will of God” (1 Pet. 4:2).

- Justice. Doing what is right toward your fellow image bearers. I’m aware that ultimately to do right to people is to do right before God. For example, “Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world” (James 1:27). However, for the sake of our discussion, I’m thinking of justice in a narrow sense here.

- Personal. Living rightly before God as an individual: “offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, dedicated to God and pleasing to him” (Rom. 12:1).

- Social. Living rightly before God as a corporate community, namely, as the body of Christ: “Carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ” (Gal. 6:2).

If we pair these dimensions in all possible combinations, we get four manifestations of righteousness: personal piety, social piety, personal justice, and social justice. This can be illustrated by the Window of Righteousness. Think of this four-paned window as a picture of how the gospel plays out in individual lives and society.

The Bible itself clearly covers the whole window, and when we do theology we should do likewise. Therefore, when the body of Christ is fully functional, all four panes will be engaged. Unfortunately, for a long time most of us in the evangelical community have been functional on one pane—personal piety. This means we’ve neglected 3/4 of the gospel’s implications in this four-fold framework.

This neglect skews our perception of righteousness and leads us to see social piety, personal justice, and social justice as outside the scope of God’s work. Consequently, we’ve tended to let other people lay claim to the other dimensions of the biblical witness—and even redefine them for purposes contrary to the gospel.

This has made our ability to function in those dimensions even more difficult for us. Such is the case with “social justice.” Thus, when the subject of social justice comes up, the knee-jerk reaction is often “I don’t want to have anything to do with that”—giving us further justification for neglecting it.

If we in the body of Christ let unbiblical understandings of “social justice” prevail, then the social justice commanded by God in Scripture will remain unmet. Social justice is a biblical concept, and we must make a clear distinction between true social justice and today’s distortions of it.

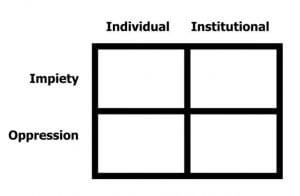

Window of Unrighteousness

The window of unrighteousness is the photographic negative of the window of righteousness. The four dimensions are:

- Impiety. When a person sins and suffers his or her own consequences.

- Oppression. When a person sins and forces others to suffer the consequences, or when he or she imposes their sin on someone else.

- Individual. Face-to-face intentional sin.

- Institutional. Sin that is woven into the structure and social fabric of society. It’s sin that doesn’t need the intention or the consciousness of the sinner to have effects on its victims.

As in the first window, if we pair these dimensions in all possible combinations, we get four manifestations of unrighteousness: individual impiety, institutional impiety, individual oppression, and institutional oppression. This can be illustrated by the Window of Unrighteousness. Think of this four-paned window as areas of life needing Christian discipleship.

Similar to our truncated understanding of righteousness, we tend to fight the battle against unrighteousness primarily on the upper left-hand pane—individual impiety. This means that we’ve withdrawn from 3/4 of the task of Christian discipleship.

This withdrawal has opened the door for others to redefine and corrupt the other three manifestations of unrighteousness—turning them into monsters we want to avoid. But these manifestations belong in the cross-hairs of a fully functioning church.

As in the case of the first window, we must make a clear distinction between the biblical concept of unrighteousness and today’s distortions of it. We must take back how unrighteousness is framed.

Observations About Both Windows

If we can learn how to be the body of Christ, then we can learn to engage and fully address both windows. Some of us are better at personal piety than social justice, and vice-versa. Others of us are better at uprooting institutional oppression than individual impiety, and vice-versa. But every act of righteousness needs to be incorporated into the larger project of justice in God’s kingdom, and every expression of unrighteousness needs to be addressed. There’s no righteousness in the land if the people have an “A+” in biblical personal piety and an “F” in biblical social justice.

As a body, we need to learn to undertake and address these diverse manifestations of righteousness and unrighteousness together. If we work together as a body, we can almost completely cover both windows. “If one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together” (1 Cor. 12:26).

Each pane of the window depends on the support of the other three panes. If one pane is removed, the integrity of the whole window is compromised. The removal of each additional pane further degrades the window’s integrity, and the last pane left will be so stressed that it will reach a breaking point.

I suggest that this is the current state of the American evangelical witness. We focus primarily on the upper-left-hand pane of each window, but much of the rest of the window is broken. Yet we cling to a sense of satisfaction that we got a 100 percent in less than 25 percent of the project. We’re not helping or participating in the bigger picture. Rather than trying to reduce our witness to a single pane, we must work together as the body of Christ to pursue this bigger picture of righteousness and address this bigger picture of unrighteousness.

To glorify God, we must be wise in our theological efforts. To succeed we must be like the men of Issachar, who “understood the times, and knew what Israel ought to do” (1 Chron. 12:32).

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.