Last month, 50 people were charged with scheming to get students into elite universities. While some of the charges involved falsifying student athletic abilities, most revolved around the standardized achievement tests nearly every college student takes: the ACT and SAT.

Some parents paid for false learning-disability diagnoses, which gained their children extra time to take the exams. Others paid “a really smart guy” to take the tests for their children or to doctor wrong answers. Still others provided copies of their child’s handwriting along with their bribe, so a proctor could write a better fake essay on the student’s behalf.

The admissions scandal—which snared celebrities such as Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman—was the largest ever prosecuted in the United States. And it raised a lot of questions about those tests.

“Is the College Cheating Scandal the ‘Final Straw’ for Standardized Tests?” The New York Times asked. The Washington Post wondered the same thing: “Is it finally time to get rid of the SAT and ACT college admissions tests?”

Probably, says Jeremy Tate, co-creator of the four-year-old Classic Learning Test (CLT). But not because of the cheaters.

Tate has been working in the college admissions arena for years. He’s watched the test—and the public schools it was built for—move farther away from education’s historical aim of cultivating truth, goodness, and beauty.

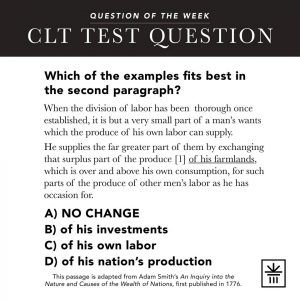

When the SAT was revamped in 2016, Tate was frustrated enough to co-create a new test. The CLT pulls from authors like Augustine, John Calvin, G. K. Chesterton, and Flannery O’Connor, among dozens of other classic thinkers. (Though the test isn’t specifically Reformed, or even Christian, the author of the initial pilot test is Presbyterian.) It also asks students to solve math problems not by memorizing formulas but by applying logic—testing aptitude instead of accomplishment.

This spring, more than 10,000 students took the CLT. More than 150 colleges—mostly Christian liberal-arts colleges—are now accepting those results.

“It has the potential to be a real disruptor to the system,” said Keith Nix, who heads Veritas School in Richmond, Virginia, and sits on the boards of CLT and the Association for Classical Christian Schools. That’s the same language philosopher Charles Taylor uses, and in some senses, the new test has the same aim.

Taylor says disruptions can jar our modern “buffered” selves—which have mentally closed the door against transcendence—into remembering spiritual reality. In the same way, the CLT pushes against enlightened humanism and puts the focus back on the transcendence of the human soul along with the capabilities of the human mind.

And that disruption, if it continues to grow, could affect the whole system.

Standardized Tests

In the 1800s, the passage of students from high school to college—generally something only wealthy white males were able to do—was a chaotic mess. Every high school had its own curricular standards for graduation, and every college had its own admissions examinations.

In an attempt to organize the system and to make college more accessible, 12 colleges banded together in 1900 to administer the first College Entrance Examination Board test. For the first 15 years, the test covered subjects such as Latin, Greek, French, history, and physics. Students were asked to translate passages of Cicero and to “describe a method of finding the specific gravity of a solid heavier than water; of a liquid.”

A few years later, a Harvard professor used an IQ test to help the military—which was looking for officer candidates—sort more than a million World War I recruits. Impressed, the College Board developed a version for high-school students. It became the first version of the SAT.

A few years later, a Harvard professor used an IQ test to help the military—which was looking for officer candidates—sort more than a million World War I recruits. Impressed, the College Board developed a version for high-school students. It became the first version of the SAT.

The exam was thought to be foolproof in a couple ways. First, since the reading sections in particular were regarded as “probably non-coachable,” it would be impossible to cheat. And second, since aptitude and ethnicity were thought to be linked, it would keep higher education off-limits to those who weren’t white.

Neither turned out to be true, but the test did begin to standardize admissions. For the next 60 years, the SAT grew in popularity, mainly due to lack of competition and skyrocketing demand. In the late-1800s, just 1 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds attended college, rising to 15 percent after World War II, then to 35 percent in the 1960s. By 2016, nearly 70 percent of high-school graduates enrolled in college.

But they didn’t all take the same test. Over the years, the math section was taken out, tested separately, and put back in; analogies came and went; the antonym section was reduced and then changed to multiple choice. In 1959, the SAT’s monopoly was broken by the Academic College Testing (ACT), which judged mastery—or what a student had learned in high school—rather than aptitude.

Popular perception is that the ACT is easier; by 2012, more students were taking it than the SAT. Together, the tests have become an enormously lucrative industry. In 2017, the SAT’s Educational Service earned $1.4 billion and ACT Inc. brought in $353 million—not including the billions spent on outside test-prep services.

As the two fought for market share, they began looking more and more alike: The ACT added a reading section and optional essay like the SAT; the SAT dropped analogies and added charts and graphs, similar to the ACT.

And both keep adjusting in order to mirror the changing curriculum and standards of K-12 schools.

That’s exactly the problem, Tate says.

Common Core

Tate spent a couple of years teaching in New York City before he went to seminary. (He wound up taking classes at both Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia and also Reformed Theological Seminary in Washington D.C.)

“Through RTS, I became enamored with the way education was called ‘formation’ for much of church history,” Tate said. “It had to do with cultivation, with shaping your heart and mind.”

Tate learned that modern educational theory was largely influenced by atheist and secular humanist John Dewey in the early 1900s. Dewey’s theory that education is fundamentally pragmatic—a way to prepare students for useful careers—changed the course of learning in America.

Tate learned that modern educational theory was largely influenced by atheist and secular humanist John Dewey in the early 1900s. Dewey’s theory that education is fundamentally pragmatic—a way to prepare students for useful careers—changed the course of learning in America.

After graduation, Tate didn’t become a pastor. Instead, he began working with schools on SAT prep. So he was watching closely when, in 2015, College Board president David Coleman announced a major overhaul to the SAT.

Coleman was one of the main architects of Common Core, the state benchmarks for reading and math in grade school and high school. (Tate’s not a fan: “Common core is anti-fiction, anti-classic literature, anti-philosophy.”) Its emphasis on utilitarian skills shows up in the SAT’s “practical, more realistic” math scenarios and the trading of classical literature for passages in social studies and science. In one sample test, students read from Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome (written in 1911), Richard Florida’s “The Great Reset” about the economic recession (2010), Ed Yong’s “Turtles Use the Earth’s Magnetic Field as Global GPS” (2011), and a speech by Congresswoman Barbara Jordan on impeaching Richard Nixon (1974).

Observers noted that the new SAT was “a lot more like the ACT,” aiming to test mastery over aptitude.

The idea is to “be more fair” by “rewarding students for what they learn in the classroom,” Tate said. “But which classroom? A Jewish classroom? A Montessori classroom? A classical Christian classroom? They’re talking about public schools. Everybody has to be assessed by public-school standards.”

The idea is to “be more fair” by “rewarding students for what they learn in the classroom,” Tate said. “But which classroom? A Jewish classroom? A Montessori classroom? A classical Christian classroom? They’re talking about public schools. Everybody has to be assessed by public-school standards.”

That’s a problem, because “I was seeing consistent themes of always censoring any Christian or theistic authors,” he said. “In addition, they were censoring any ideas that would possibly be offensive to a student. So you end up with meaningless content—you end up with passages about penguins, because no one says, ‘I had a bad experience with a penguin that is going to trigger me.’”

He hated it. “I thought maybe I could offer test prep for a different test,” he said. “I started researching who was making a new test and found that nobody was doing it.”

He wondered if he could do it himself, and called up nearly a dozen college admissions counselors. They told him that they’d love a different test, but that making one would be nearly impossible. The creators of the SAT and ACT spend years—and millions—painstakingly testing each question that’s included.

Tate didn’t have millions, and he didn’t have years. But he did have an idea motivating enough to attract a “strong and enthusiastic” team.

Classic Learning Test

Tate asked his crew to write questions on the best passages of literature, philosophy, and religion. They added questions that would test mathematical reasoning—such as metaphors and logic puzzles—along with math skills and knowledge.

“On the CLT, the passages to be read came from great works of Western literature, as well as classic novels and essays,” wrote homeschooled senior Olivia Dennison, who took the test in 2017. “It was obvious . . . that the goal of the CLT was to cultivate truth, beauty, and goodness in a student. It was a fun test. It made me excited for the future of testing. The required passages were works that I had either read, or that I would read on my own time. Instead of the ACT passage I read where an author remembered how much fun he had on the beach as a child, the CLT included writings from Boethius and C. S. Lewis. I even answered questions about a scene from The Picture of Dorian Gray.”

“On the CLT, the passages to be read came from great works of Western literature, as well as classic novels and essays,” wrote homeschooled senior Olivia Dennison, who took the test in 2017. “It was obvious . . . that the goal of the CLT was to cultivate truth, beauty, and goodness in a student. It was a fun test. It made me excited for the future of testing. The required passages were works that I had either read, or that I would read on my own time. Instead of the ACT passage I read where an author remembered how much fun he had on the beach as a child, the CLT included writings from Boethius and C. S. Lewis. I even answered questions about a scene from The Picture of Dorian Gray.”

Dennison’s experience is what the test creators were going for—and, for the most part, are achieving. Ninety-three percent of Veritas students said it was a “more satisfying experience” than taking the SAT, Nix said.

The CLT is meant to be a throwback to the days of the Founding Fathers, when education “was aimed, most fundamentally, at making a person more fully human,” Tate wrote.

It’s also a step into the future, especially given the steady growth of the neo-classical education movement.

Classical Advantage

The CLT is not a perfect solution; for example, it doesn’t solve the racial inequality in education. And students of any race who have studied classically have an advantage.

That’s not new—classical students, on average, already do pretty well on the ACT and SAT. “Our little schools exceeded by 60 to 100 points the average of prep schools on the reasoning component of the SAT between 2000 and 2015,” said Association for Classical Christian Schools president David Goodwin.

But in order to keep doing well as the tests change, “we’d have to change our curriculum to Common Core, which we don’t want to do,” he said. That’s why the CLT has him “jumping up and down.”

“I want a test that can measure verbal and quantitative reasoning—that will be the test that will accurately reflect what we do,” he said.

The first CLT was administered in 2016, and the content wasn’t the only difference students noticed.

“When you take the SAT, you go to a testing location—usually an unfamiliar, factory-like school—and sign in as a number,” Nix said. “Then you go through three or four hours of testing that you’re told will determine where you’ll go to college, which will determine your whole life. You take it under a tremendous amount of pressure. And then you wait a month to see how you did.”

The CLT is administered on the students’ own campus and takes just two hours. The results are delivered the same day.

“It makes the experience smaller,” Nix said. “It puts things in perspective.”

Because the test is just one part of an imperfect admissions process—an overhyped part, some argue. In fact, a growing list of colleges—including the University of Chicago and Wake Forest University—are going test-optional.

“In a perfect world, I wouldn’t want the CLT to exist, because I think that education is fundamentally a humane exercise, and the best way to assess anything is person to person,” Goodwin said. “I’d rather have the schools put forth their best graduates to the best colleges, who accept them on the word of the schools. That keeps education from being a grade.”

Nix is also skeptical of grades; his school just did away with them for grammar school.

But he acknowledges “if it’s a good standardized test, then it’s a helpful check-and-balance on the quality of what you’re doing. If we have a great books list, but the way we’re teaching it doesn’t help kids read classic texts and do some good thinking and demonstrate understanding, then we need to know that.”

Goodwin likes a Luke 6:40 model of education, where a teacher reproduces himself in his students. “I don’t think a test can measure that—not the CLT or the SAT. But the redemptive power of the CLT is it gives us headroom to do education well without being pulled into the vortex that is coming.”

It may do even more than that.

Teaching to the Test

It only took a year before large high schools like Veritas were administering the CLT. At the same time, Hillsdale College had completed a yearlong vetting process, and Wheaton statistics and psychology professor John Vessey “did most of the research on the psychometric properties of the CLT to establish that it was just as reliable and valid as the SAT or ACT to use in college admissions decisions.” (He told TGC, “I believe it to be an excellent alternative.”)

“When Hillsdale endorsed it as a superior test over the SAT and ACT, things were different from that moment on,” Tate said. By 2018, the number of high-school test takers had grown to 10,000. More than 150 colleges now accept the results, including Wheaton College, Baylor University Honors College, Biola University, and Cedarville University.

The test’s rising popularity could be a harbinger.

“Our goal long-term is to go mainstream,” Tate said. “If we can get to 60,000, then 80,000, then 100,000 students, it’s hard for anybody to stay on the sideline.”

If you’re looking to fill seats, as more colleges are, then accepting CLT test scores sounds like a good idea. Nearly a quarter—22 percent—of CLT test-takers don’t take any other standardized test.

“This is already happening,” Tate said. “We’ve gotten a handful of schools on board who aren’t missionally aligned.”

Tate loves that. Because he knows that teachers teach to the test. So it follows that making a good test—with questions about great texts, ethics, religion, and logical reasoning—will encourage teaching to those standards.

“The CLT has the potential to be a real disruptor,” Nix said.

Kimberly Thornbury, vice president for strategic planning at The King’s College in New York City, uses the same language. King’s was one of the first places to accept the CLT on applications.

“This seems like a strategic disruptor,” she said. “Taking CLT scores is a small way we can take leadership in changing curriculum or affirming a K-12 curriculum we think is going to help.”

Classical Renewal

“There’s a fun classical Christian education revival going on,” said Kirk Vander Leest, who sits on the board of both the CLT and the Society for Classical Learning. (In April, he’ll join the CLT staff.) “CLT is a huge part of that.”

Like the original college entrance test, the CLT is organizing and setting the bar for schools, thought leaders, and curriculum providers. The 2018 CLT Summit “was the first time we could get much of the classical Christian leadership into the same room,” Nix said.

And “it does raise the standard on classical Christian schools that have big aims but might not be executing as well as brochure might advertise,” said Nix, who was nervous to get his school’s results. “I was like, ‘I think we’re doing a good job, but how will we do?’” (Veritas placed first in the nation in CLT scores this spring.)

“Tests are so important to how we think about what an education is for and how we assess it,” Classical Academic Press CEO Chris Perrin said. “So if the CLT could perform a similar role—be an important kind of culminating test but be aligned with the curriculum of the great books, great conversations, great ideas, mathematics—this would just help create a kind of energy, drive, and focus for the entire renewal. And indeed, it’s showing itself to be doing that right now.”

That’s exciting for parents, teachers, and administrators who see education as more than utilitarian.

“Our Lord can act—and does—in 10,000 different ways,” Vander Leest said. “We feel this is a movement of his kingdom and his people and for his church. That’s why we’re in this.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.