I eagerly read Gregory Coles’s Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity as soon as I received it. In some respects, Coles and I have a lot in common: we’re both Christians who have a same-sex orientation but believe that we honor Jesus best by denying that desire. In other respects, our lives are incredibly different. He’s male; I’m female. He grew up in the church and overseas with a full-throttled, homeschooled evangelical upbringing; I grew up as an atheist in America. Later he lived in culturally conservative places in America, while I’ve always been enmeshed in bicoastal liberality.

Despite those differences, I deeply resonated with his description of his attractions: how natural they are, how unthinkable to change them. He uses a thought experiment for straight people that I’ve often employed with friends: Imagine being told by the church that you must feel sexually aroused by your best same-sex friend. It’s effective—it helps straight Christians understand how intractable orientation can feel.

Failed by Christians

Exercises like these are necessary because the church has often failed people struggling in this way—by encouraging revulsion toward gay people and suggesting they must become straight to fulfill God’s command. Coles has been mistreated by some Christians, and he describes what it was like to grow up feeling ashamed of the feelings that well up within him. He was closeted for a long time.

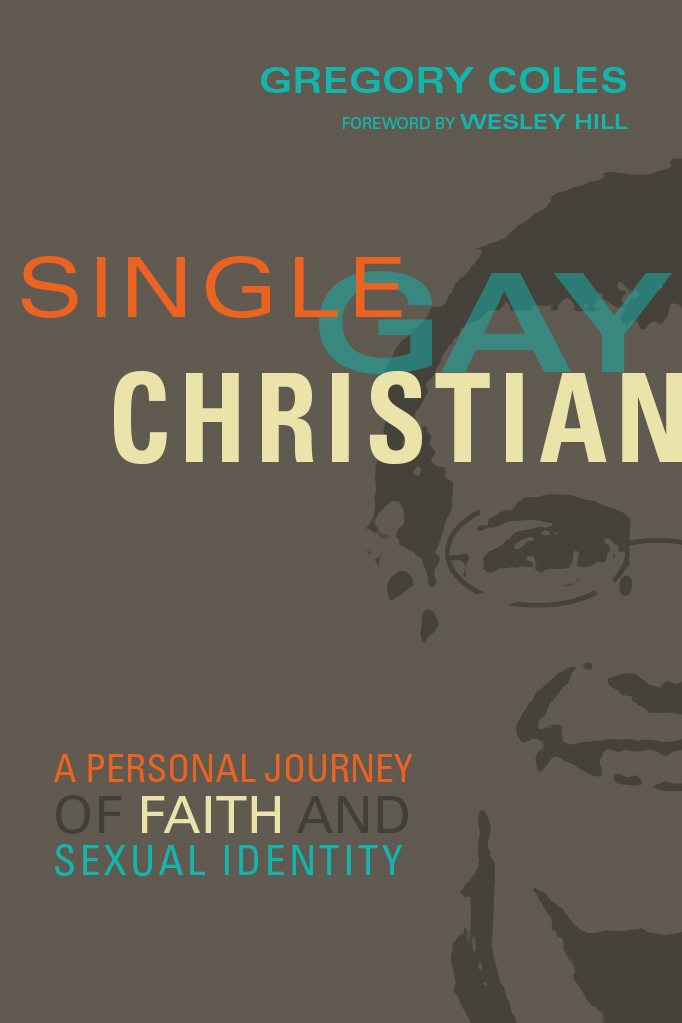

Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity

Gregory Coles

Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity

Gregory Coles

This is hard for me to fathom, since I never experienced shame about my feelings. They arose before I became a Christian, and when I entered the church, I learned that while my attractions were a part of the fall, their persistence after my rebirth didn’t condemn me. I never had to wonder what people would think of me, since everyone has always known I’m attracted to women and has treated me well. If anything, I’m sometimes treated like a hero among conservatives for becoming a Christian, when I certainly don’t deserve it.

Because of those different experiences, Coles and I diverge on label preferences. We both aim for honesty and clarity, which I find heartening. He, however, balks at the term “same-sex attracted” due to its connection with the ex-gay movement. He prefers “gay” because it doesn’t gloss over what he experiences, even though he’s aware that in the church it can carry the connotation of one who acts on their desires. I’ve never preferred “lesbian” for myself, because it seems to encompass far more than the simple attraction I feel. I actually like “same-sex attracted”; I don’t feel, like Coles, that it makes my orientation a passing phase.

Need for Clarity

There is so much that I loved about this book. Coles and I agree on what the Bible says about sexuality, and he writes about his choice of obedience with grace and good humor.

But the one place where I felt disappointed was the section beginning on page 108, where he leaves space for this to be an agree-to-disagree issue—where we could “share pews with people whose understanding of God differs from ours” (109)—and compares it to the disagreement about modes of baptism. He writes, “[I]f I’m honest, there are issues I consider more theologically straightforward than gay marriage that sincere Christians have disagreed on for centuries” (108).

Of course sincere Christians disagree on baptism, but on that question there are arguments on both sides that make sense of the Bible as a whole. By contrast, Scripture’s witness on sexuality is painfully clear. Rather than hold out the possibility that the Bible might be okay with homosexual relationships—which I believe is likely to damage those in the thick of same-sex desires—I’d rather affirm in the strongest terms that God is clear, and plead that his Word be read.

If we allow the new affirming view as a valid option for the Christian, even if inferior to the traditional view, I believe, with Don Carson, that we make a disastrous pastoral and theological move, because we end up allowing some of those who claim Christ to persist in sin.

We see Coles begin down this path a bit when he compares a same-sex married Christian to a straight, sexually impure Christian woman. He lines up theologically with the second woman, but then asks, “But whose life is most honoring to God? Who really loves Jesus more? Who am I going to see in heaven?” These questions are beside the point. Why should we ask which professed believer loves Jesus more? We don’t need to compare these women’s sins; we need to plead with both to repent and move forward in obedience.

He moves on from this comparison by saying, “Other people’s hearts are none of my business” (110). And that’s where my heart broke. Let me explain why.

Coles ends that episode with a call to Romans 14:4: “Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another? It is before his own master that he stands or falls. And he will be upheld, for the Lord is able to make him stand.” Yes and amen, let’s live that Scripture. But we also need to live Hebrews 3:12–13: “Take care, brothers, lest there be in any of you an evil, unbelieving heart, leading you to fall away from the living God. But exhort one another every day, as long as it is called ‘today,’ that none of you may be hardened by the deceitfulness of sin.”

These verses plead for us to care about how sin destroys our brother and sister’s heart. How can that be none of our business?

It took a lot of courage to write this book, and I admire Coles for that. I’ve prayed more than once for his spiritual protection. And I would even encourage people to buy and read this book, as the core of it is moving and helpful. But I wish our generation as a whole would show courage in clearly calling out sin, and exhorting each other to flee it—all types, all kinds.

Related:

- Can We ‘Agree to Disagree’ on Sexuality and Marriage? (Trevin Wax)

- Why Can’t the Church Just ‘Agree to Disagree’ on Homosexuality? (Kevin DeYoung)

- A Two-Minute Clip on Homosexuality Every Christian Should Watch (Sam Allberry)

- You Are Not Your Sexuality (Sam Allberry)

- Isn’t the Christian View of Sexuality Dangerous and Harmful? (Sam Allberry)

- How Can the Church Help Those Battling Same-Sex Attraction? (Sam Allberry)

- What Christians Just Don’t Get About LGBT Folks (Rosaria Butterfield)

- Why Is God’s Sexual Ethic Good for the World? (Jackie Hill Perry, Sam Allberry, Rosaria Butterfield)

- How Celibacy Can Fulfill Your Sexuality (Sam Allberry)