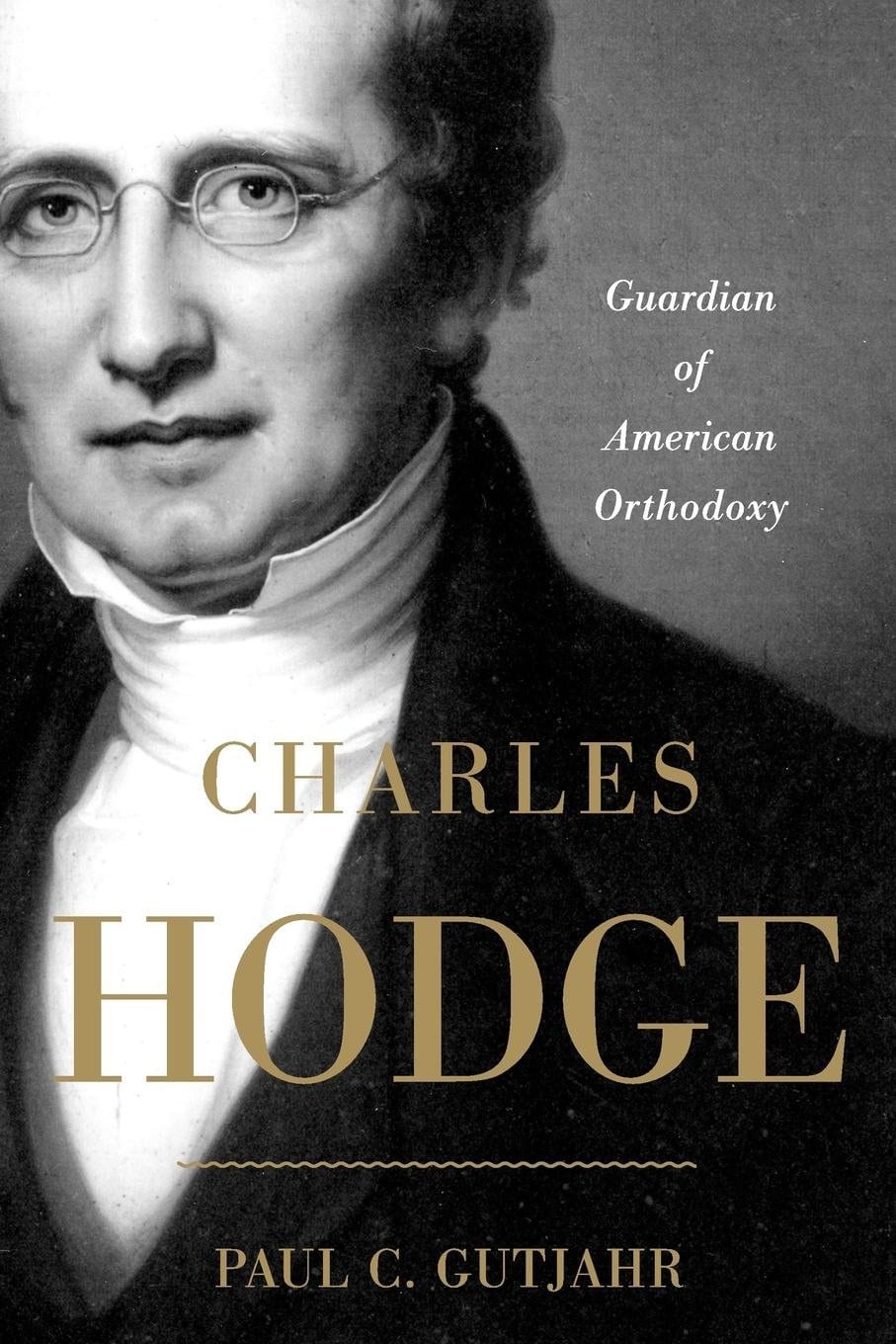

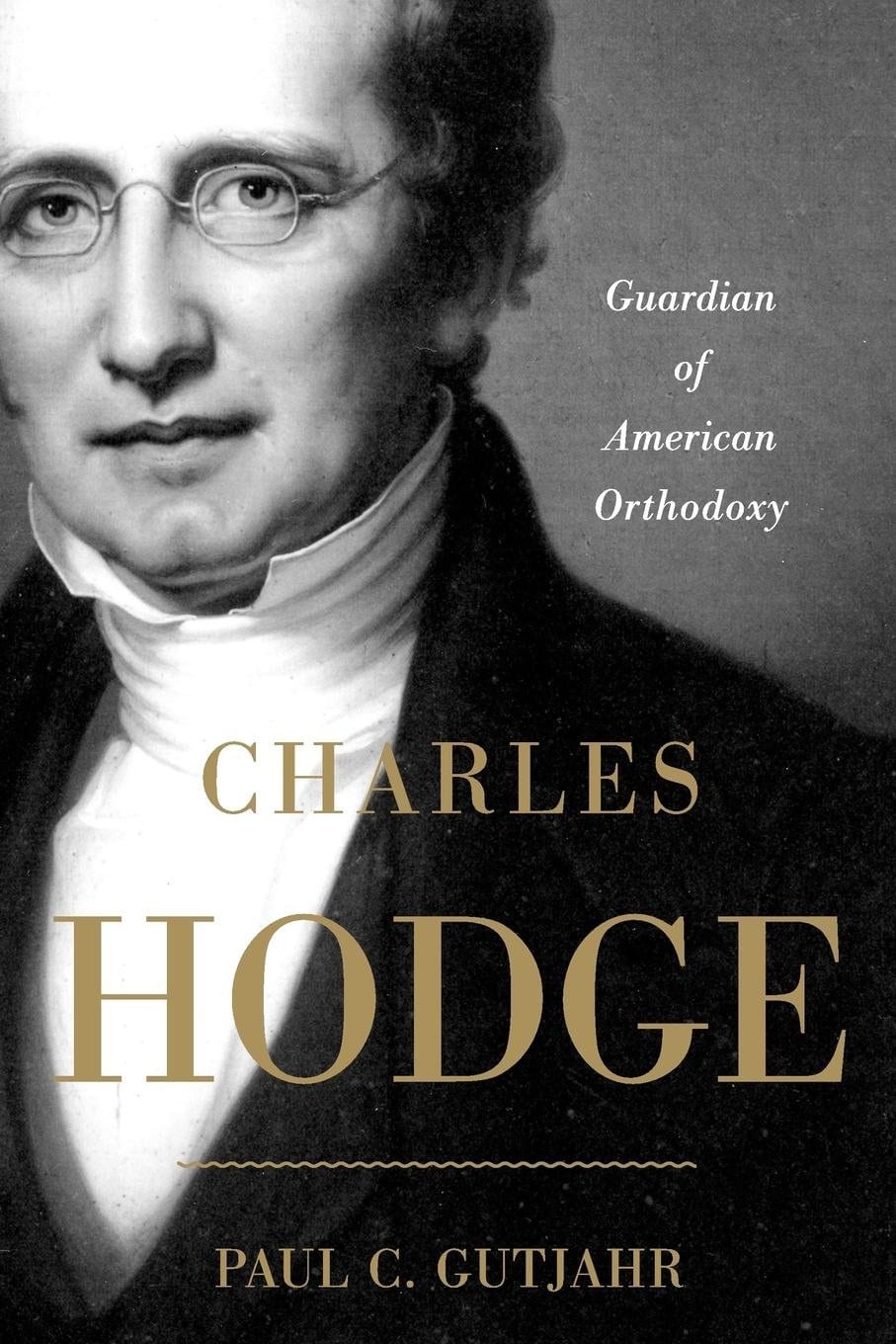

Charles Hodge is a name familiar to many but a man known to few. As a pillar of orthodoxy in an era of theological modernity, Hodge was a dominant figure in 19th-century America. But in the last century his legacy has been reduced to mixed reviews of his three-volume Systematic Theology. Paul Gutjahr, associate professor of English at Indiana University, has the potential to fill this informational lacuna with Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy.

Hodge’s 21st-Century Context

To set the context of this biography, it is important to realize how Hodge has become a whipping boy for contemporary theologians. On the evangelical left John Franke, in Beyond Foundationalism, speaks pejoratively of Hodge’s scholasticism and rationalistic foundationalism. He overlooks the way Hodge’s commitment to Scripture differs from Cartesian foundationalism, and how this churchman sought to unite theology and practice, as in his popular devotional, The Way of Life.

Simultaneously, on the evangelical right, Kevin Vanhoozer, in The Drama of Doctrine, charges Hodge with de-dramatizing Scripture and wrongly attempting to create an “epic” theology that reduces the Bible to a collection of propositions. Yet he too overlooks the fact that Hodge was a New Testament exegete before he was a systematician. In short, while many have taken shots at Hodge, few have gotten to know the man behind the “storehouse of facts” approach to theology.

This is why Paul Gutjahr’s book is so important. Now after a decade of research, his magnificent biography, Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy, opens to the rest of us a view of this erudite and affectionate theologian.

Repairing Misconceptions

Broken into eight sections, one for every decade of Hodge’s life, Gutjahr manages to synthesize large and often weighty subjects into short chapters. Moreover, since Gutjahr depends almost entirely on primary resources—personal letters, classroom notes, journal entries, etc—the book reveals much of Hodge’s personal life. Still, while it warmly introduces Hodge, the book is not hagiography.

Gutjahr points to Hodge’s strengths, while also exposing his weaknesses. He is fair in his treatment of Hodge’s views on slavery, pointing out his nuanced understanding. However, Gutjahr shows greater bias as he represents Hodge’s view on men and women. Gutjahr blames Hodge’s extensive study of Paul and his patriarchal mentors for his own view that men are superior to women. However, this term (superior) is Gutjahr’s, not Hodge’s. Gutjahr describes Hodge in complementarian terms, and judges that his view makes men superior. In my estimation, this appraisal says more about the egalitarian views of Hodge’s biographer than of Hodge himself (251–55).

Gutjahr follows Hodge to Europe as the uncertain young theologian takes two years to improve his academic calling. Leaving his family behind, Hodge journals about all of his experiences. Encountering some of the most prominent (read: liberal) scholars of his day, Hodge remained steadfast in his commitment to Calvinist orthodoxy. Gutjahr attributes this to his steadfast constitution, but one wonders if there is not something more. Is Hodge’s consistency merely the reactive product of his childhood’s vacillations? This is Gutjahr’s supposition. Or is it more the case that Hodge is a man committed to the never-changing Word of God?

Charles Hodge: Guardian of American Orthodoxy

Paul Gutjahr

Charles Hodge (1797–1878) was one of nineteenth-century America’s leading theologians, owing in part to a lengthy teaching career, voluminous writings, and a faculty post at one of the nation’s most influential schools, Princeton Theological Seminary. Surprisingly, the only biography of this towering figure was written by his son, just two years after his death. Paul C. Gutjahr’s book is the first modern critical biography of a man some have called the “Pope of Presbyterianism.”

Returning to Princeton more confident in his academic abilities, Hodge set to the work of teaching a full load, producing commentaries, and writing theological journal articles. From these works, it is evident that the Scriptures were his stabilizing force and also the source of much controversy. For instance, his commentary on Romans was a concerted effort to respond to the deficient views on imputation posited by Moses Stuart and Albert Barnes (Barnes’ Notes). Still in print today, Hodge’s commentary on Romans, evinces the kind of scholar Hodge was—erudite, articulate, and exegetical.

While teaching, writing, and editing the Biblical Repertory, Hodge did not neglect his church. Gutjahr covers much of the turbulence of 19th-century Presbyterianism through the life of Hodge, and shows how many of the motions Hodge made in the general assembly failed. Though revered, he was not able to keep to peace when tensions arose between Northern and Southern Presbyterians over slavery. Later, when the Presbyterian Church sought reunion, Hodge stood opposed because of the theological compromise this would entail.

More Influential than Acknowledged

Gutjahr’s presentation of Hodge is informative and stimulating. Commendably, with only a few exceptions, he lets Hodge’s voice be heard. Gutjahr helps the reader understand the context of Hodge’s life, and thus he supplies a close and comprehensive picture of this eminent Christian, theologian, professor, and churchman.

Not leaving Hodge in the past, Gutjahr concludes by noting the significance of Hodge’s legacy for the church and academy. Recognizing that Hodge conjoined orthodox Calvinism and Scottish Common Sense Realism, Gutjahr points to the way he influenced future generations. He posits that the content of his theology was carried on in places like J. Gresham Machen’s Westminster Seminary and James P. Boyce’s Southern Seminary. Gutjahr also asserts that Hodge’s “scientific” methodology prepared the way for evidentialists such as E. J Carnell and Josh McDowell, while his theological method was carried on in the systematic work of Lewis Sperry Chafer.

Unfortunately, these connections are asserted in brief and not substantiated, leaving the reader to wonder if these assertions would survive scrutiny. Either way, they will challenge students of Hodge to ask how the light of this man’s life has illumined the theological landscape since his death, for it is evident from reading this biography that his influence was larger and more positive than most contemporary theologians acknowledge.

In the end, Gutjahr’s work is a rare combination. It matches well-researched scholarship with an easy reading style. For pastors or professors who have consulted Hodge’s Systematic Theology, Gutjahr has provided an illuminating book on the life of this theological giant. Just the same, for those who have never read Hodge, Gutjahr’s book is a persuasive invitation to become friends with this “Guardian of Orthodoxy.” As it concerns research, this book provides a portal for seeing firsthand the people and the debates of 19th century. In this way, it is an important read for historians examining American Presbyterianism. Even if you’re just looking to read a really good biography about a man whose life has much faithfulness to consider and imitate, Gurjahr’s book is a wise selection.