Virtually every day some media story tells us what “evangelicals” believe—usually what they believe about some political issue. I have become convinced that many of these stories are simply unreliable. The primary reasons that they are unreliable are (1) the difficulty in getting solid polling data on any subject, (2) unclear definitions of “evangelicals,” and (3) ideological biases against “evangelicals” among pollsters and reporters.

Observers have noted that ever since the advent of cell phones, reliable polling has become ever more difficult. Polls routinely get no more than a 10 percent response rate. Some academic experts (including colleagues of mine at Baylor) have begun to despair about using polls to gather reliable information about anything at all. FiveThirtyEight gave a good, balanced overview of the problems in polling four years ago. The problems have only gotten worse since then.

The second issue is that many polls depend upon self-identification to determine who is an “evangelical.” Some polls do use other means of determining who an evangelical is, such as church affiliation. But typically, pollsters simply ask a person if they identify as an evangelical. If the answer is yes, then that person is taken to have “evangelical” views about Donald Trump’s latest antics, or whatever the topic is. This is highly dubious. For instance, if you ask more probing questions, it turns out that significant numbers of these “evangelicals” do not go to church.

In many cases, we have no idea how many of these “evangelicals” read the Bible regularly, have been born again, or share other hallmarks of historic evangelicalism. As I have argued repeatedly, I suspect that large numbers of these people who identify as “evangelicals” are really just whites who watch Fox News and who consider themselves religious.

To be fair, many polls do explicitly break out white voters from blacks, Hispanics, and others. And if my hunch is correct, it would be worth investigating how the term “evangelical” became a code term for a kind of nominal Christianity in America. But the fact remains that “evangelicals” are usually an indistinct mass in these stories.

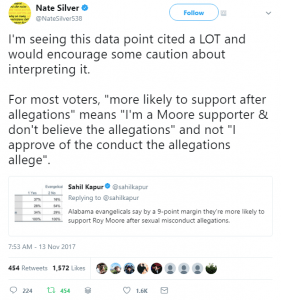

Finally, the news media love stories on “evangelical” hypocrisy. A perfect example was a recent story which suggested that many “evangelicals” were more likely to support GOP Senate candidate Roy Moore because of allegations of inappropriate sexual conduct and dating of minors.

Anyone who thought about this for a second should have been incredulous. Would anybody tell a pollster that allegations that a candidate had sexually abused minors would make them more inclined to support that candidate? Nate Silver called out this silly interpretation on Twitter:

Whoever these “evangelicals” might be, they’re obviously saying that they don’t believe the charges against Moore, and they’re sticking by their man in the face of “fake news.” (I’m not trying to defend Moore here, I’m just suggesting that the power of the “fake news” theme gives Moore’s defenders a ready response against the explosive charges women have made against him.)

But this is part of the fundamental problem with polling: there are so many possible meanings left open by the way a question is framed, the context in which it is asked, the person responding, and the reporter interpreting. The media will undoubtedly keep using such statistics, because reporting on polling is such a popular staple in all forms of news media.

Before you read a story and despair about the state of evangelicalism in America, pause for a second. The reality about evangelicals may indeed be bad and disheartening. But are polls supplying reliable information about “evangelicals” and their beliefs?

Sign up here for the Thomas S. Kidd newsletter. It delivers weekly unique content only to subscribers.