The urgent-care clinic in Dallas opened at 9 a.m. But when The Gospel Coalition reporter got there at 9:15 a.m., it was closed.

The walk-in-only clinic, which can accommodate about 45 people a day, was already full. Patients had lined up before the doors opened, and the staff counted in the men, women, and children who could be seen that day.

“If we kept the doors open, it wouldn’t end,” medical manager and lead clinician Ryan Martin said.

The free clinic is less than five years old, a partnership of Watermark Community Church and Questcare Medical Services (a network of physicians).

“For years, one of the top three vocations represented here [in Dallas] has been folks in the healthcare arena,” said Jeff Ward, Watermark’s director of external focus. “I’d get a lot of doctors and nurses and medical professionals who’d say, ‘I’m happy to serve a snow cone in other service opportunities, but I’d really love to use my [medical] skill set.’”

I’m happy to serve a snow cone in other service opportunities, but I’d really love to use my [medical] skill set.

He’d direct them to community clinics run by nonprofits, but “we faced challenges such as lack of patients, supplies, or training.”

At the same time, access to healthcare was “a huge problem,” Ward said. Texas has the highest number—and the highest percentage—of uninsured people in the country. The state is home to 4.5 million of the nation’s 28.1 million uninsured.

The more Watermark worked in the lower-income areas of Dallas, the more it ran into the same problem.

Smaller issues like infections can “compound into emergencies” when families can’t afford healthcare, clinic director Christy Chermak said. “All of the sudden, illness isn’t the only issue they are facing, but also missed work and significant financial setbacks.”

Then Matt Bush, a physician who belongs to both Watermark and Questcare Medical, came to Ward with an idea. What if the two partnered on a charity clinic—one that offered both physical help and also spiritual guidance?

“He was leading the staffing at a city hospital just down the road from us, and said that a large percentage of folks coming through the doors were unfunded,” Ward said. “They were using the emergency room as their primary healthcare vehicle.”

Bush thought a low-cost or free clinic could handle the minor injuries, infections, and diseases that cost the hospital—and the patients—millions to take care of through the emergency room.

So in 2013, Questcare Medical and Watermark gave it a shot. They set up the QuestCare Clinic in a densely populated (90,000 people within a two-mile radius), almost entirely unchurched (95 percent), underresourced (98 percent of elementary school students get free or reduced lunch), dangerous (fifth-highest violent crime rate in the city) neighborhood. (Best part: It’s just five miles from the church building.)

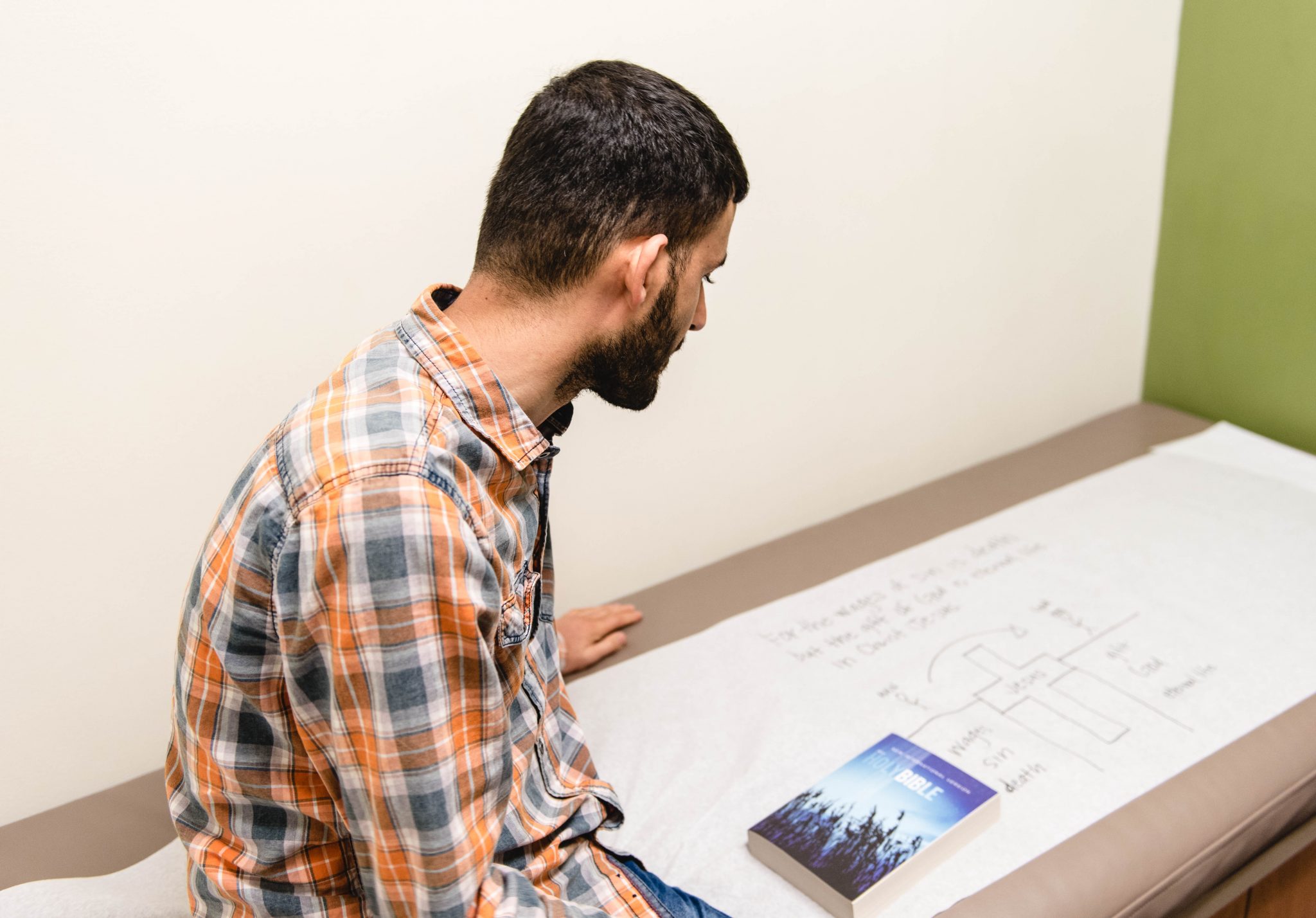

QuestCare’s name is on the sign, but the Watermark presence is impossible to miss. Most of the six full-time staff and 175 volunteers attend the church. Behind the receptionist’s desk is a desk for the pastoral care volunteer—QuestCare always has someone dedicated to spiritual and biblical support on hand. Each examination room is stocked with Bibles, which patients are encouraged to take home. And the flags next to each exam room door, indicating whether a patient has been seen, include one for spiritual engagement.

“It’s amazing to see what a prime opportunity it is,” Ward said. “People are already acknowledging brokenness in their life. They’re ready and open to ask questions, to hear counsel, to be offered solutions.”

At least once a week, QuestCare has seen a patient profess faith in Christ.

Last year, QuestCare’s staff saw almost 10,000 patients. They figure they’ve saved local hospitals $5 million and saved patients more than $24 million. They’ve handed out thousands of Bibles, prayed with tens of thousands of patients, and drawn the Romans Road over and over again on tissue-paper bed rolls. At least once a week, QuestCare has seen a patient profess faith in Christ.

It’s not light work—many of the patients are refugees, and all are under-resourced. Opening up spiritual conversations can be as draining as it is invigorating. And having to turn away people who need help never gets easier.

“Daily, we seek the welfare of our city by meeting the physical and spiritual needs of those in our own backyard,” senior pastor Todd Wagner said. “People from all different faiths, ethnicities, and socio-economic backgrounds are loved and cared for in the name of Christ. It has also allowed us to engage city leaders and healthcare professionals with the idea that God wants to use the local church to redeem brokenness in every facet of society.”

Patients

When Mina, her husband, and their two children arrived in Dallas from a southeast Asian country, they had $2,000, a visitor’s visa, and a desperate desire to stay. (Mina isn’t her real name.)

“I was so worried,” she said. She had reason to be—her Muslim family was violently strict, and had beaten Mina for her interest in Christianity.

Determined not to go back, Mina enrolled her son in public school. The administration asked her for a sports physical, but she knew she didn’t want to go to the local hospital. She’d been there already, for an infection in her son’s foot, and was charged more than $600.

The school gave her a list of free clinics, and she chose QuestCare.

“When we entered, I felt a very warm welcome,” she said. “They were all very friendly. I cannot explain it—I don’t have the words. They were all very sweet.”

The staff noticed her anxiety, and after several visits she was willing to tell them her story. It was the first time she had openly talked about the abuse and violence she had seen leveled against those who believed in Jesus.

“I think I’m in the right place. Can I trust you with this?” Mina asked, knowing her family was still a target.

She absolutely could. Chermak connected Mina to a member at Watermark, who connected her to a legal team that is helping her with immigration. Mina and her husband now have jobs and an apartment, and the children are in school. Best of all, they embraced the gospel and are now members at Watermark.

“She’s one of those stories that keeps us doing what we’re doing,” said Chermak, who keeps a photo of Mina’s baptism—done at Watermark in 2016—in her office.

Another patient is a refugee from the Middle East who fled after being jailed for speaking out against Islam. He made his way to Dallas, and a school nurse referred him to QuestCare when he came down with a cold. One of the staff drew the Romans Road on the examination-table paper and gave him a New Testament. Two months later, he came back to the clinic to tell them, “It has to be Jesus.”

Liana Banales, a nurse on staff, was at the front desk when a woman called in, looking for abortion services. Instead, Banales offered to direct her to a local pregnancy center. Through a week’s worth of back-and-forth phone calls, Banales prayed and advocated for—and eventually won—the life of the child.

But the patients aren’t the only ones with good stories.

Volunteers

“I was serving in the children’s ministry when I started hearing at church about QuestCare,” Watermark member Paige Delgado said. The hospital and ICU nurse thought, Maybe this would be an even better place to use my gifts.

When Bush and Ward built QuestCare, they intentionally left room for volunteers to fill key staff positions, wanting church members—not paid staff—to serve the city. But that approach came with challenges.

“When I came in 2015, we had the typical volunteer culture,” Chermak said. People were relaxed about how often they worked and what time they showed up.

“We cleaned the slate,” she said. They let go of all their volunteers, then asked them to re-apply if they could commit to four-hour (or more) shifts twice a month (or more). They aren’t kidding—if volunteers don’t show up, they’ll be getting a call.

“It’s a chance to shepherd your people on what commitment means, on your ‘yes’ being yes,” Chermak said.

Reliability “shifted drastically” after the new expectations were put in place, she said. “We’ve found that the more we raise the bar and set high expectations for our team, the more likely they are to exceed them.”

One of those “high expectations” is asking volunteers to engage spiritually in every room.

“It’s our goal to start a spiritual conversation with every patient that comes through our door,” Chermak said. “Just like in Matthew 10:12–14, some conversations go farther than others. It is not our job to force something, but to see what God is already doing in that patient’s life and encourage them in their next steps on their faith journey.”

It’s our goal to start a spiritual conversation with every patient that comes through our door.

That can be scary for volunteers uncomfortable with sharing the gospel.

“I love to be a nurse—that’s easy,” Delgado said, recalling her initial thoughts on volunteering for QuestCare. “But don’t make me evangelize. I don’t feel comfortable talking to people about that.”

She remembers Martin telling her, “Go discharge that patient and pray for her.”

“I was like, ‘What? You’re crazy,’” Delgado said. But she did it.

Delgado made it through the conversation without passing out, throwing up, or dying. So did her patient.

“It hit me—I can do it,” she said. So she tried it again. “It took a year before I started to feel comfortable, like maybe I’m equipped to do this. It’s a lot of opening your mouth and trying.”

Now she’s the full-time operations manager at the clinic, and trains volunteers on how to share the gospel with patients.

“Medical personnel are good at asking questions [about physical problems], at being detectives,” Martin said. He’s doing the same thing, only spiritually. “I’m digging into conversation, and then I can shift a little and say, ‘Tell me more about that,’ or ‘Tell me a little more about yourself.’ If I see some anxiety or stress, I can ask about that, and then all of a sudden they’re crying and telling me everything.”

It isn’t always smooth.

“I’ve messed up so many times, and put my foot in my mouth,” he said. “But you have to practice—have to do it, just like anything else.”

He remembers one nurse who came out of an exam room with hands shaking. She had just shared the gospel with a patient for the first time.

The nurse became one of their most faithful volunteers, and “now she’s doing it at her hospital,” he said.

Which is the frosting on top—not only does the clinic address the physical and spiritual needs of under-resourced patients, it also inadvertently trains medical volunteers to offer that same holistic care at their places of employment.

Evangelism

Not everybody wants a spiritual conversation, and that’s fine, Martin said. By now, he’s grown practiced at being able to tell who is spiritually open and who isn’t.

Most are, he said. Research bears this out: 50 percent to 90 percent of patients want to be asked about their religious beliefs. (Understandably, the desire goes up as the diagnosis worsens.)

Watching God connect volunteers with patients is one of the best parts of the job, Chermak said. For example, one volunteer has experienced a rough patch in her marriage. On the days she serves, “it feels like patient after patient is experiencing the same thing,” Chermak said. “This volunteer gets to sit across from them and say, ‘Hey, me too. Let’s talk about it.’”

The same thing often happens with languages, she said. Texas resettled 84,000 refugees between 2002 and 2017, more than any other state but California. In 2016, more refugees moved into Dallas-Fort Worth than any other metropolitan area in the country.

More than half of QuestCare’s patients were born outside of the United States (56 percent); the clinic has logged visits from citizens of 118 of the world’s 195 countries. (They stock Bibles in eight different languages.) Some of the volunteers speak Arabic or Farsi or Amharic, and it seems like the days they’re working often see an increase in patients who speak the same, Chermak said.

“When I first started, I pitched the idea to change our tagline to ‘this place is crazy,’” Chermak joked. “I told friends if they needed a reminder that God was still in the business of crazy adventures like we read about in the Gospels, all they needed to do was come hang out with us for a day.”

Finances

QuestCare’s clinic is clean and well-constructed, with brightly colored walls, an X-ray machine, and a stockpile of medical supplies. They even have two dental rooms (volunteer dentists come in once a week).

It’s a clinic that should’ve cost around $400,000 to build. But it didn’t.

“With construction, we had another chance for the body of Christ to use their gifts,” Chermak said. Watermark has around 7,500 members, among them architects and electricians and HVAC experts who donated labor and supplies.

The clinic’s operating costs this year are about $740,000. Most of that comes from Watermark (the clinic makes a budget request each year), Questcare Medical (the physicians group donates “significantly”), and private donations. None of it comes from insurance or government funding.

QuestCare asks patients for a $10 donation, if they can afford it. (“We want them to know they have a say in what’s happening here,” said Chermak, who has read When Helping Hurts.) The average patient donation is $7; last year, that netted the clinic $79,000.

Medical City Hospital, which is four miles away, has been supportive, supplying the X-ray equipment and a translation service, and referring more than 700 patients a month to QuestCare. So has the city—a city council member was the one to guide them to their location.

It’s easy to see why. QuestCare is the only nonprofit drop-in urgent-care clinic around, and Chermak estimates the services they provide have saved patients—who otherwise might have hit the emergency room without insurance—more than $24 million in hospital fees. They’ve saved the hospital—which eats about $250 each time an uninsured patient comes through on an urgent care matter—about $5 million.

Watermark

It’s impossible to tell how many of QuestCare patients make their way over to Watermark.

“I’ve heard stories of women showing up to children’s church with our discharge papers, saying, ‘Somebody told me to come here,’” Chermak said. “Recently, a coworker told me someone in the membership class mentioned the clinic was their first touch point with Watermark. We hear of things like that happening all the time.”

Some patients are already Christians. In fact, Ward once bumped into a church planter in the clinic lobby.

“He said, ‘This is a real blessing for us, because we don’t have any benefits through our planting organization,’” Ward said.

Secret Sauce

When QuestCare first hung its shingle back in fall 2013, patients were not lined up 30 deep before 9 a.m. Only about 5 to 10 people found their way in each day.

“That’s back when I would check somebody at front desk and then call them back and then treat them,” Martin said with a laugh. “I was always changing hats.”

Beyond passing their name around to local schools, other low-income clinics, and some local apartment buildings, they haven’t advertised. Word of mouth—and the cold and flu season—have been the biggest magnets.

But by the end of 2016, the staff “saw the writing on the wall that we’d max out our facility,” Chermak said. On May 21, they’ll open a slightly smaller clinic 20 miles away in Plano, an area with far fewer low- or no-cost healthcare options and—critically—a Watermark campus.

There’s no “secret sauce” to reaching the 30,000 people QuestCare staff have served over the past four and a half years, Chermak said.

“The reason we’re seeing God do these things is it’s his church sitting across from those patients.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.