Can Christianity be made respectable?

Should the impulse to make it respectable be faulted?

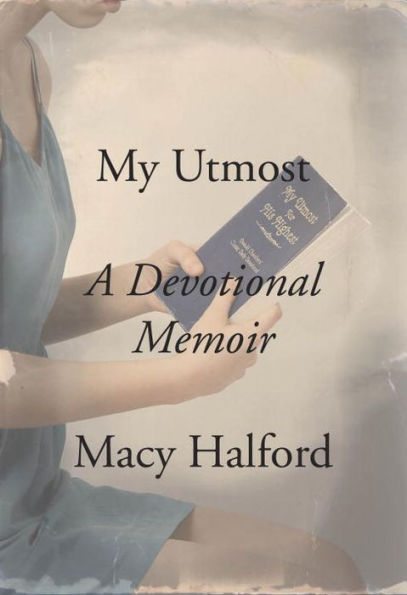

Those are my lingering questions after finishing Macy Halford’s My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir, a spiritual memoir that traces the biography of Oswald Chambers and the legacy of his words.

My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir

Macy Halford

Christian Respectability?

Respectability—in Halford’s circles of Barnard friends, New Yorker colleagues, and the “mountaineer” with whom she falls in love in Paris—is not something easily granted to Christianity. At its most suspicious, evangelical identity implies that people have failed to “grow a brain” (as one colleague puts it). Nevertheless, if anyone can parlay the evangelical experience into the otherworldly realms of urbanity, it might be someone like Halford—with educational and professional pedigree as well as occasional fondness for cigarettes and cocktails. To boot, she writes the book from France.

Even if there are “as many evangelical Christianities as there are evangelical Christians,” Halford’s experience seems as normative as the evangelical experience gets. She grew up in the Southern Baptist heart of America, where she attended First Baptist Church of Dallas, pastored by the likes of W. A. Criswell, elected SBC president in 1968 with apologies for his formerly “blind” embrace of segregation, and Robbert Jeffress, whose defense of Donald Trump (“I want the meanest, toughest, son-of-a-you-know-what I can find”) aligns him with the conspicuous white evangelical vote in the last election.

Halford’s mother and grandmother who raised her model a sincere, everyday faith. Her church does the real job of caring for its members. She wants to emphatically say she has traveled far from that place and those days. And yet, for all the distance she puts between her evangelical childhood and her cosmopolitan adulthood, her story doesn’t reject her upbringing or the influence of Oswald Chambers’s daily devotional—even when it’s reported George W. Bush also reads it religiously.

Halford attempts to translate faith for the outsider, to interpret her own faith story, and to make Christianity a little more credible—all through My Utmost for His Highest, both its words and its author. It was “a book my intellectual friends and colleagues would appreciate, if they were only made aware of it,” and Halford wonders if it wouldn’t “make evangelicals a bit more respectable in their eyes?”

In many regards, Chambers is fit for his task. He commends open-minded inquiry: “Always make a practice of provoking your own mind to think out what it accepts easily.” He reads Dickens and Darwin, Nietzsche and Wilde. His is an active, emotional, devout faith—not blind, passive, uncritical, or cold.

Bridging the Gap

When Halford aims to make Christianity respectable, I understand her impulse. Her “liberal,” “pluralistic,” “globalized,” “democratic,” and “commercial” circles are my circles, too. Six years ago, I moved from Chicago to Toronto with my husband and five children. On one hand (and fewer than four fingers), I can count the number of Christian families at my children’s entire school. The churches in my city are being torn down in favor of towering condominiums. My children’s youth group numbers less than ten. When I mention my Christian faith in casual conversation with neighbors and school friends, I’m met with tacit suspicion, as if I’ve just admitted a deeply cherished belief in unicorns. The safest religion in this city is the most nominal one.

Seeking respectability—in the way I think Halford and I intend—is not about moderating the unequivocal and exclusive claims of the gospel or denying our essential “otherness” as Christians. There is an immovable stone of stumbling that no amount of intellectual gravitas can lift (cf. 1 Cor. 1:23). Rather, it is about finding ways to bridge the gap of unnecessary misunderstanding, something that must happen if friendship is to continue—and with it, witness. As Halford writes, “You ask me why I’m in Paris, and why I’m religious. . . . The better question might be why I’m religious in the way that I’m religious, and not in another way.”

If we seek respectability, it’s only to ensure that if anyone stumbles, it’s over Christ they have fallen—and not, as one important example, our politics.

Attempts at respectability are efforts to waylay unfounded suspicions that end conversation before it’s even begun. In other words, if we seek respectability, it’s only to ensure that if anyone stumbles it’s over Christ they have fallen—and not, as one important example, our politics.

Halford’s My Utmost reads like this kind of deliberate attempt at sustained conversation between evangelical “insiders” and their skeptics. The book is well-poised for this cultural moment that has been readied for evangelicals: to say what the gospel really means and what we’re really about. And maybe we’d find more Macy Halfords in newsrooms like The New Yorker if we reminded young people that all work—not just vocational Christian service—is consecrated to the glory of God.

Chambers Redux

Early in his life, Oswald Chambers toyed with becoming a painter. At one point, he was convinced of his calling to art. In a letter to a friend he wrote:

My life work as I see it, my eternal work, is, in the Almighty strength of God, to strike for the redemption of the aesthetic kingdom of the soul of man—Music and Art and Poetry, or rather, the proving of Christ’s redemption of it. . . . As far as my limited knowledge goes, our Master and Savior has no representative to “teach, reprove, and exhort,” and an ambition, a longing has seized me and seized me so powerfully that it has convinced me of the need.

This artistic calling, for various reasons, was never realized, and Chambers entered the ministry. Maybe Halford is taking it up instead.