My high school history courses emphasized big themes and simple explanations for cause and effect. Those classes were designed to give some sense civilization formed in the Fertile Crescent, why the Roman Empire fell, and the way punitive reparations contributed to Hitler’s rise. In this model, the distance between history and our daily lives seems like an uncrossable ditch. History in textbook format can quickly become a tool for political activism that distorts the past and empowers evil.

I also experienced history more personally growing up. I spent numerous summer days wandering a musty brick building, looking at glass cases of old buttons and arrowheads as my grandmother, the curator of the county historical museum, helped visitors look up where ancestors had lived and were buried. For me, history always had more to do with cemeteries and censuses than textbooks and political triumphs. That approach to history is more consistent with the messy reality of a fallen world, but it doesn’t do much to inspire grand political movements.

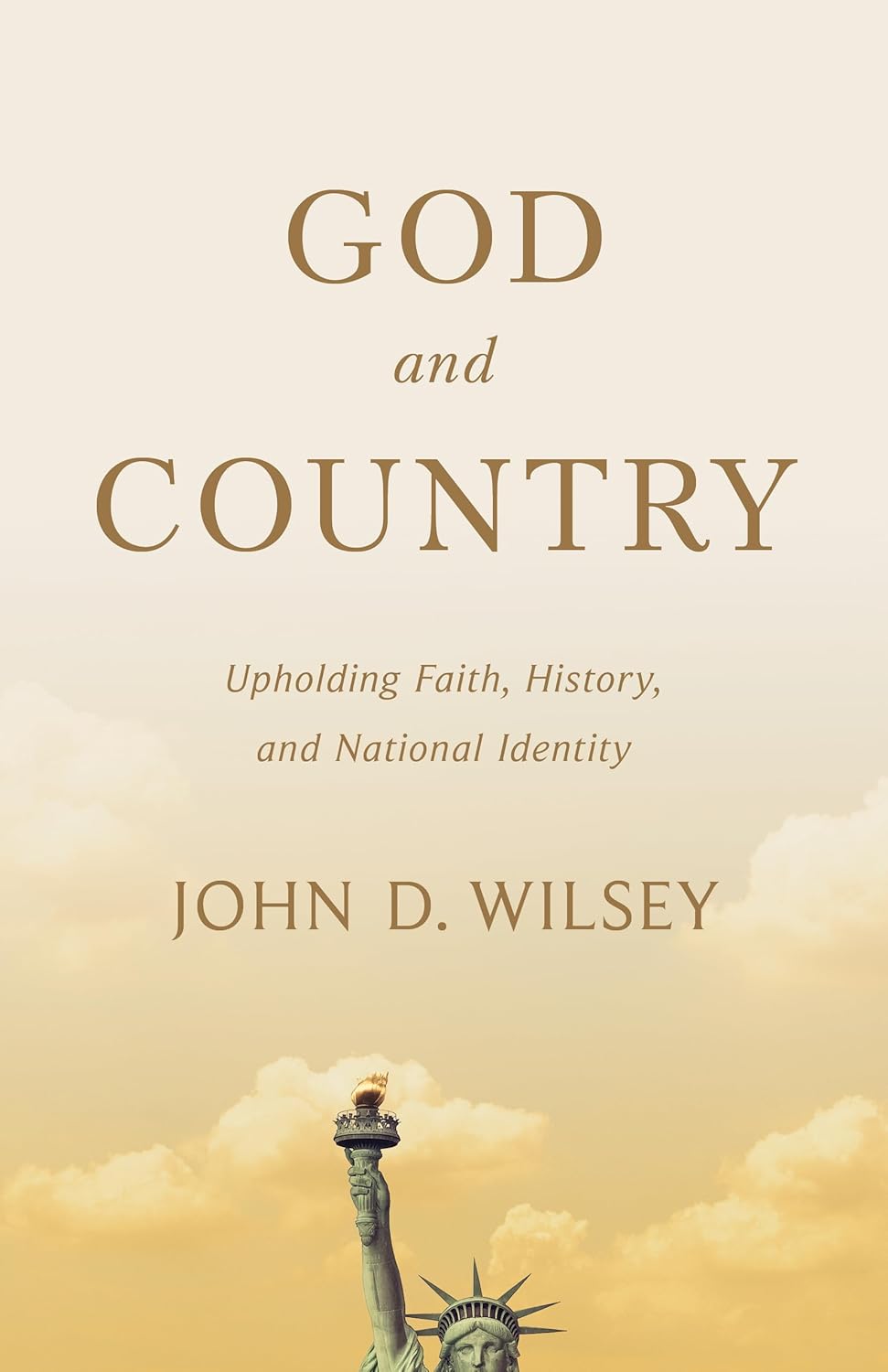

In God and Country: Upholding Faith, History, and National Identity, John Wilsey, professor of church history and philosophy at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, argues that a virtuous approach to history helps us love our nation while recognizing its flaws. Along the way, he shows that since Christianity is a uniquely historical religion, we should have a special interest in rightly handling history. This is an engaging and encouraging book for those seeking to faithfully navigate between political extremes.

God and Country: Upholding Faith, History, and National Identity

John D. Wilsey

God and Country: Upholding Faith, History, and National Identity

John D. Wilsey

Is nationalism always a threat to Christian faith? In God and Country: Upholding Faith, History, and National Identity, John D. Wilsey argues that nationalism is a complex phenomenon with varied expressions, some dangerously opposed to Christianity, others potentially compatible with a biblical worldview. Wilsey demonstrates how nationalism can become a surrogate religion, even cloaking itself in Christian language, and illustrates that this danger isn’t confined to one side of the political spectrum.

Christians as Historians

History matters for Christians because our religion is uniquely historical. As Wilsey notes, “If the Bible is historically wrong, then we have nothing to rely on for the truth of Christianity but the heart” (34). This is why Christians must embrace a virtuous approach to history.

For example, amid a vigorous theological debate about the Trinity and the person of Jesus Christ, the Council of Nicaea zoomed in on the historical facts surrounding Jesus’s death. “For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate” comes just a few lines before the declaration of Christ’s resurrection and ascension to heaven. Theologically, it doesn’t matter which Roman official ordered Jesus’s execution, yet millions of people repeat that historical fact every week as they recite the Nicene Creed in gathered worship.

But facts alone aren’t the substance of history. “History is our interpretation of the past based on the artifacts that are left over,” argues Wilsey. “The facts of what happened in the past are there, but we make sense of those facts differently as time and circumstances advance” (8). Christians need to become virtuous historians. We need to apply virtues like faith, hope, love, wisdom, and justice to our treatment our neighbors from another age so we can give them the respect they deserve.

Wilsey shows that, in reality, every Christian is a historian of sorts. As we wrestle with the copious evidence for Jesus’s bodily resurrection, we interpret the value of eyewitness testimony against our own uncertainty. More significantly, as we consider the facts recorded in Scripture and in extrabiblical sources, we need to come to grips with our culture’s distorted view of time.

Reckon with Time

Loving our ancient neighbors is often challenging because we live in a largely ahistorical age. As Sarah Irving-Stonebraker argues, “The premise underpinning the idea that our lives are a matter of self-invention is that there are no enduring stories shaping our identities and providing normative direction to public life.” We experience a timeless, eternal now filtered through the silicon rectangles in our hands. This will only get worse as AI animations of historical figure blur the boundaries between past and present.

Every Christian is a historian of sorts.

At the root of a Christian approach to history is recognizing the goodness of time. Time was created by God and has meaning. Wilsey observes, “God’s purpose for time was for it to be measured and that the standards for measuring time would be predictable, knowable, and permanent” (34). Thus, studying history is as much an exploration of God’s good creation as staring through a microscope.

Time gives us a sense of our place in the world. One of the defining attributes of prison life is to be “sequestered from the public, outside the flow of the world’s identifying and unifying narratives” (47). When we lose a sense of time, it robs our lives of a sense of meaning.

I’ve experienced this reality when living for months underwater on a submarine. Children had been born, a World Series had been won, and my wife had started a new job. Yet my memory of that time was confined to a relentless cycle of 18-hour, sunless days inside a steel tube. Those months are hard for me to fit within the rest of human history.

A right understanding of time is essential for Christians because it enables us to understand the ancient truths preached from our pulpits each Sunday. Peter wasn’t just a character in the Bible; though he lived long ago, he was a real man who feared death and heartbreak of failure. The events in our Bible really happened in time and space to people who (with one exception) lived as sinners in a sinful world.

Virtuous Historians

As Americans recognize the 250th anniversary of our nation’s founding, temptations abound to fixate on the legitimate evils in American history or uncritically celebrate the Christian character of many of our founders. Wilsey is critical of both extremes.

A key point of God and Country is that a virtuous approach to history helps us avoid the ahistorical perspectives of anti-American cynicism and Christian nationalism. “Being an American means being part of a great tradition,” Wilsey explains. “America is not perfect, but America is the greatest champion of human freedom in history” (155). No history, much less that of our nation, can be accurately represented by a black-and-white framing.

Good history requires a biblical perspective on humanity. We all have mixed motives, a tendency to be selfish, and the potential to do great evil. One day, our lives will be summarized by the dash between the dates on our headstones. Neighbor love requires us to treat the dead—some of whom we’ll meet in eternity—as complex people living in confusing times rather than as two-dimensional caricatures.

Good history requires a biblical perspective on humanity.

A virtuous approach to the past requires us to “begin our reading of history by reading ourselves.” After all, Wilsey argues, “How we think about the people, events, and ideas of the past is directly connected to the kind of people we are and aspire to be” (132). That means the way we handle the sinful actions of slave-owning founding fathers needs to reflect an understanding of our status as simultaneously righteous and sinners.

This book is well written and deeply personal. It’s an excellent introductory volume on the method of history, particularly for American Christians. Though graciously articulated, Wilsey’s argument is unlikely to convince deeply invested critics on either side. Nevertheless, God and Country equips Christians to love their country without worshiping it and to critique its sins without despising its gifts.