In this lecture, Don Carson examines John 3:1–21 to discuss the complexity of the gospel, emphasizing its transformative nature. Carson critiques the view that the gospel is merely a gateway to discipleship and highlights the importance of being born again. Carson explains that new birth involves supernatural transformation, grounded in God’s love and action.

He teaches the following:

- The gospel: good news about what God has done in Christ’s cross and resurrection

- The historical context of the Reformation and the Great Awakening

- Nicodemus’s significance as a Pharisee and a member of the Jewish council

- The new birth as a miraculous, supernatural transformation, not just a change of mind

- Why Jesus could speak authoritatively about the new birth

- How Jesus’s crucifixion parallels the bronze snake in Numbers 21

- Why Jesus’s unique revelatory claim is central to understanding the gospel

Transcript

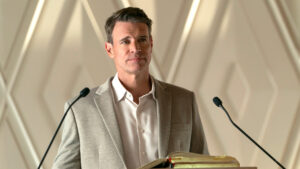

Don Carson: It’s an enormous privilege to be with you for this regional conference of The Gospel Coalition. I’m sure many of the other pastors who work with me on the Coalition’s council would love to be here with me, but you’re stuck with me for the day!

The topic that has been given to me is.… What is the Gospel and How Does it Work? If you had asked me to talk on that subject 15 years ago, I would have said, “Everybody knows what that is. Give me a break!” But about 10 years ago, some of us started asking students at the seminary where I teach and in churches and so on, just asking open-endedly, “What is the gospel?”

We heard the most amazing variety of answers! “The Bible says that the gospel is ‘Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ.’ ” Is that the gospel? That’s something that you do to respond to the gospel, but is it the gospel? Don’t you have to make some sort of distinction between what the gospel is and how you respond to it?

“Jesus says, ‘The first and most important commandment is, “Love God with heart and soul and mind and strength.” And the second is like unto it: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” ’ That’s the gospel.” Is that the gospel? How do you know? Why or why not? “Well, the gospel is all about salvation, which is about getting ready for eternity. It’s also about social justice.” Is that the gospel? Why or why not?

It suddenly struck me that we have a whole lot of people who use gospel words, but they don’t mean the same thing. In theory, we believe we’re all talking about the gospel and saying how wonderful it is, but we mean very different things by it. We’re using the same words, but we’re like ships passing in the night. We’re on different pages.

The gospel is, first and foremost, news. It’s good news, but it’s news. What do you do with news? You announce it. That is to say, the gospel is news about what God has done and is doing. In the Bible, it is, first and foremost, what God has done in Christ, supremely focused on his Christ and resurrection and all that springs from that. It is what God has done and is doing. What you do with news is announce it.

Now, granted that that’s what the news is, there are important ways to respond to it. That’s part of the preaching of the gospel, all right, but you still want to distinguish between what God has done that you’re now announcing and talking about and the entailments of how it should be lived out. There is a distinction between the two.

Otherwise, if you move immediately to the entailments of how it should be lived out, then every “gospel” message turns into mere moralizing. Then it’s indistinguishable from any other kind of moralizing religion, except you throw in a few “Jesus” words and things like that. So I am persuaded that one of the most fundamental things that we have to do today is to recapture accurately, holistically, and comprehensively what the gospel is.

Moreover, in some of our circles (we come from a variety of denominations, I’m sure) the gospel is a fairly small thing. Even when we get that it’s bound up with news about who Jesus is and what he’s done, it’s a small thing that tips us into the kingdom. It gets us saved. Then after that, you have your discipleship courses.

You have your training patterns: how to be happy though married, 16 ways to bring up nasty little kids, how to be more sanctified than you really are, and all those sorts of things. There are lots and lots of these courses with wonderful titles. Then throw in some courses on Christian leadership and so forth. So the gospel is the little thing that tips us in, and then all the life-transforming stuff comes along in our discipleship courses afterward. We’ve bought into that.

But when you look at how gospel, the word itself, is used in the New Testament, one of the things that strikes you, especially about Paul, is that gospel is not the little category that gets you in and discipleship the big category. Instead, gospel is the big category. It’s focused on Jesus and what he’s done, what God has done in Christ, supremely in the Christ and resurrection, no doubt. But it is the big category that does all the transforming work. The gospel is “the power of God unto salvation,” not the little thing that tips us in.

So part of our business is to work out, from the New Testament itself, all the different things that the Bible says the gospel does, how it does it, and why it does it. There’s no way we’re going to get to much of that today; there just isn’t time. But in three of the four addresses, especially, I want to talk about central things bound up with what the gospel is in the New Testament. Even when the word gospel isn’t used, it’s a focus nevertheless on what God has done to reconcile men and women to himself and all that that means, what it looks like, and what we ought to be teaching and preaching and announcing.

We’re going to begin with the new birth and what it means to be born again. Historically, it’s worth remembering that in the history of the church, people have sometimes focused on one aspect of the gospel or another, depending on the debates that were going on at a particular time. For example, at the time of the Reformation, in the sixteenth century, a lot of the debates turned on what justification is, how men and women are reconciled to God. We’ll come to that one in the second installment today.

But at the time of Whitefield and Wesley, the time of the so-called Great Evangelical Awakening in the eighteenth century, there was much more emphasis on being born again. Whitefield is said to have preached on John 3 three thousand times. Mind you, he often preached five times a day, so you could run up those numbers pretty fast!

When Whitefield was asked, on one occasion, “Why do you go around preaching, ‘You must be born again’ all the time? You go someplace, and all you say is, ‘You must be born again. John 3. You must be born again.’ Why do you keep emphasizing that?” He would say, “Because you must be born again.” Somewhere along the line, we need to see how it is so integrated into the understanding of what the gospel is, and into the understanding of what Jesus has done, that it becomes central to our life and thought.

But before the day is out, I want to list some other elements to the gospel so that we don’t restrict our thinking of what the gospel is to being born again or to justification. There is a comprehensive vision in all of this that we need to catch a glimpse of, and I hope that you will see more of that before the day is out.

I’m old enough to remember when the Datsun automobile underwent a name change. Most of you aren’t old enough to remember that, but I remember it. The parent company, Nissan Motors, decided that Nissan would become the base name for its cars. Here in North America, one of the advertising ditties that captured the entire marketplace for about six months was, “The born-again Datsun.” Born-again Datsun? It underwent a name change.

About the same time (it followed by some months), people started using born again in a variety of political contexts. A Republican became a Democrat or vice-versa, and then you’d hear little speeches about “He’s a born-again Republican” or “She’s a born-again Democrat” or whatever. This basically meant a change in political affiliation.

One of the things you still hear today, sometimes, is born-again Christians, which can be a mark of approbation (“Oh yes, I’m a born-again Christian”) or a mark of sneering condescension (“There are Christians, and then there are born-again Christians”). In this sense, they’re somewhat to the right of Attila the Hun; they are disgusting fundamentalists and are not to be trusted. They’re born-again Christians. Christians are all right; you can barely put up with them, but born-again Christians are just a bit over the top!

So what does the expression mean? It’s one of those expressions, a bit like gospel itself, that has come to mean so many different things depending on the context. It’s worth taking a while to figure out what it means. As far as we know, Jesus was the first person to coin the expression. What is very clear is that when he used it, the person that he was discussing matters with didn’t have a clue what it meant either. And he wasn’t a twit! He was a professor of divinity.

What we’re going to do is work through John 3:1–21 and observe the following: First, what Jesus says about being born again. Second, why Jesus can speak about being born again with such authority. Third, how Jesus brings about this new birth. And fourth, why Jesus was sent to bring about this new birth. I’m going to begin by reading John 3:1–21.

“Now there was a Pharisee, a man named Nicodemus, who was a member of the Jewish ruling council. He came to Jesus at night and said, ‘Rabbi, we know you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him.’ Jesus replied, ‘Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born again.’ ‘How can anyone be born when they are old?’ Nicodemus asked. ‘Surely they cannot enter a second time into their mother’s womb to be born!’

Jesus answered, ‘Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and the Spirit. Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit. You should not be surprised at my saying, “You must be born again.” The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit.’ ‘How can this be?’ Nicodemus asked.

‘You are Israel’s teacher,’ said Jesus, ‘and do you not understand these things? Very truly I tell you, we speak of what we know, and we testify to what we have seen, but still you people do not accept our testimony. I have spoken to you of earthly things and you do not believe; how then will you believe if I speak of heavenly things? No one has ever gone into heaven except the one who came from heaven—the Son of Man. Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him.

For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but to save the world through him. Whoever believes in him is not condemned, but whoever does not believe stands condemned already because they have not believed in the name of God’s one and only Son.

This is the verdict: Light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil. All those who do evil hate the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed. But those who live by the truth come into the light, so that it may be seen plainly that what they have done has been done in the sight of God.”

This is the Word of the Lord.

1. What Jesus says about the new birth

What did Jesus say about being born again? We’re introduced to Nicodemus. We’re told that he was a Pharisee and a member of the Jewish ruling council. Politically, Rome was the regional superpower, but it tried to organize things so that local political entities had their own governance underneath the superpower.

In Israel, that meant the Sanhedrin: the Jewish ruling council made up of 70 or 72 leaders. This was the supreme court, the judicial body, the legislative body, and the executive body. It had all of the authority under the Roman power. Moreover, it brooked no separation of church and state. The law, after all, under which they operated was, at least in theory, the law of God, given in the Bible itself. So those who sat on this council were astonishingly important in terms of political power in that small country.

Moreover, of the people who sat on that council, some were from the priestly class, some were merely aristocrats with a lot of money and clout, and some were people like Nicodemus. They belonged to a party that was theologically more adroit and more learned. Pharisees often had a reputation for being more informed theologically. They were seen as pious, disciplined, and politically, socially, culturally, and theologically conservative. They were orthodox in their beliefs.

On top of that, when you read down in chapter 3, verse 10, Nicodemus has the moniker “Israel’s teacher.” Jesus said, “You are Israel’s teacher.” That is probably a title, something like Grand Mufti or Regius Professor of Divinity. He was really up there. So in addition to being a Pharisee, Nicodemus was a learned instructor.

In those days, somebody reached that sort of status only if he had memorized the entire Old Testament in Hebrew plus a body of oral tradition about twice as long again. The apostle Paul certainly would have done that, for example, just as part of his training. It’s hard for us to imagine, because we’re not a memorizing sort of culture, but that’s the kind of man Nicodemus was.

He comes to Jesus at night, and he asks a question. One of the things you learn about John’s gospel is that John is capable of writing with enormous evocative sensitivity. When he says that Nicodemus came to Jesus at night, why does he mention that? What’s the point? Is it just because he’s interested in the time of day?

Some have speculated that maybe it’s because Nicodemus, for all of his clout, is a bit embarrassed to come to Jesus, a kind of regional itinerant preacher from Galilee, so he sneaks in at night when nobody is around to watch. I don’t believe it for a moment. When Nicodemus does show up elsewhere in this book, he doesn’t really care what people think. He’s not afraid of public opinion.

Moreover, it’s not how John uses his symbolism. John is a very symbol-laden writer. One of the things you discover very quickly about John’s propensity for symbol-laden talk is that he loves to use light and darkness, day and night. Even at the end of this section, what do we read in verses 19 and following? “This is the verdict: Light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil.” Do you see? He’s still using day and night.

Or later on, those of you who read your Bible regularly will recall that on the night Jesus is betrayed, eventually Judas Iscariot is dismissed and John comments in the text, “He went out. And it was night.” Undoubtedly, temporally it was nighttime. It was after dark. But John is saying more than that. He’s not just looking at his watch, drawing a conclusion. Judas went into the darkness of night.

So Nicodemus is already labeled here. He comes to Jesus at night. He’s in a fog. He doesn’t really see clearly. He thinks he does. In fact, his opening comment, as we’ll see, makes a claim about what he sees. “Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher who has come from God. For no one could perform the signs you are doing if God were not with him.” There are some admirable things in Nicodemus. He is the Regius Professor of Divinity, but he approaches Jesus with a certain amount of respect.

Rabbi literally means my teacher. Now rabbi wasn’t a category with legal clout like reverend, who is “revved up,” who has been ordained. That came about in the second century. In the first century, it was merely an honorific. Nevertheless, for all that he’s Regius Professor of Divinity or the ancient equivalent, he approaches Jesus, an itinerant preacher from Galilee, with a certain amount of respect. There’s something commendable about that.

But then Nicodemus makes a certain kind of claim. “We know that you are a teacher who has come from God.” We? Who is the we? Oh, people have speculated all kinds of things. We Pharisees? That doesn’t work; there are all kinds of Pharisees who disagreed. We, my students and I? But there’s no mention of students in the context. No, this sounds like a slightly pompous overtone. A little farther on, we’ll see that that is really the way you have to take it. A little farther on, it comes back to haunt Nicodemus, as we’ll see.

“Rabbi, we know … we’ve looked into this matter, and we know … that you are someone special.” There are a lot of faith healers out there, in every generation, that are charlatans or that play with psychosomatic diseases. “But you are doing miracles of quite a different order of things.” Later on in this book, one will be highlighted in that regard: a man born blind who is enabled to see (John 9).

Has anyone ever heard of a healing of a man born blind? Congenitally blind, now being made to see? “We know you are someone special, a teacher sent from God. Because the miracles you are doing are a cut up. They’re not your run-of-the-mill faith-healer-type miracles. These are spectacular. We have come to the conclusion that you are sent from God, we have.”

How does Jesus respond? One of the hardest things to get right is to follow the flow of the argument from verse 2 to verse 3. Jesus responds, verse 3, “Very truly I tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God without being born again.” Now how do you make the leap from Nicodemus’s question to Jesus’ response?

People have suggested all kinds of things, as if Nicodemus would have asked his question this way, “We know that you are a teacher sent from God, because no one could do these miracles unless God were with him. So tell us, therefore, are you really the promised Messiah who is going to bring in the kingdom or not? Is that who you are?”

Jesus reply is then, “Well, the real issue is not whether I bring in the kingdom but whether you get into the kingdom, whether you see the kingdom. So back in your face! The question is not really who I am but, rather, whether you’re going to get in.” But if that’s the way we’re to understand the connection between verses 2 and 3, there are two things that follow.

A) Jesus is really gloriously rude.

He’s one of these people who can’t wait for you to finish your question before he’s giving the answer. It would have been nice to allow dear ol’ Nicodemus to actually say what he was going to say before Jesus interrupted him and gave the answer that told Nicodemus he was wrong!

B) One of the things you discover throughout John’s gospel is that, again and again and again, no matter what the question is that is brought up, Jesus tends to bring things back to himself.

So there’s a Sabbath issue, in John 5, for example. Are you allowed to do certain things on the Sabbath? Jesus doesn’t say, “Well, let’s have a little discussion about the meaning of the Sabbath in the law.”

What he says, instead, is, “Listen. My heavenly Father works on the Sabbath and I, too, am working. I have the same rights as he does.” This suddenly raises the whole issue from being a Sabbath issue to being.… Who is the Messiah? It all focuses on him. Jesus is constantly bringing things back to himself. Whereas, on this reading of the connection between chapter 3, verses 2 and 3, what Jesus is doing is putting the attention away from himself on whether or not Nicodemus can get in. It’s not a very likely connection.

No, I think the connection is something much more straightforward. Nicodemus has approached Jesus and has said, “We claim to see certain things. We see by this powerful display, this set of miracles that are so above the run of faith healers and the like, that this really is a mark of God.” That is, a mark of God’s power, a mark of God’s reign, a mark of his authority, and a mark of his inbreaking, powerful, transforming rule.

Jesus replies, “My dear Nicodemus, you don’t see a thing. You think you see the reign of God. You think you see the kingdom of God, but I have to tell you, no one can see the kingdom of God unless they’re born again. You might see a miracle, but you really don’t see the kingdom of God. You don’t see God actually operating, actually working. You don’t see it at all. You’re still blind as a bat. You’ve just seen the miracle, but you don’t actually see the reign of God unless you’re born again.”

Then Nicodemus replies in verse 4, “How can anyone be born again? How do you climb back into your mother’s womb and be born?” Some think Nicodemus is just being literalistic. Jesus is speaking in some sort of metaphorical way. He doesn’t expect us to climb back in our mummy’s tummies. Nicodemus is too thick to understand the metaphor, so he answers in literalistic terms.

But you don’t get to be Regius Professor of Divinity in ancient Israel without being able to spot the odd metaphor now and then! That is really assigning a stupidity to Nicodemus that is really singularly unlikely. Nicodemus was not a fool. It may be that he heard that Jesus was promising too much. Most conservative Jews in Jesus’ day longed for the coming of the kingdom. They longed for the coming of the messianic, Davidic King. When he came, he would restore Israel’s greatness, turf out the Romans, and there would be righteousness prevailing in the land.

In this light, Jesus now can be understood to be saying that we need something more than that. We need new men and women, not new institutions. We need new lives, not new laws. We need new creatures, not new creeds. We need new people, not mere displays of power. But how do you generate new people?

Most of us, I suggest, in this room, have felt the pressure and wished, at some point, we could start over, at least in some part of our lives. Do you ever wake up in the middle of the night and have some sort of flashback about some time when you were so stupid or when you did something so ugly or so embarrassing? You sort of break out into a cold sweat in the half-dawn between being awake and being asleep. You wish to God you could go and live that bit over again. Am I the only one who has experienced this?

That’s just embarrassment at the horizontal level. Imagine someone actually beginning to feel embarrassed like that before God. You wish you could do things over. Or as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, an English Romantic poet, said, “And ah for a man to arise in me; that the man I am may cease to be!” Most of us have felt that that if we have any sort of moral sensitivity at all, haven’t we?

Or the poet John Clare said, “If life had a second edition, how I would correct the proofs.” Of course, truth be told, if life had a second edition, we’d muck it up just as badly the second time around, but we’d like to think, at least, that we’d correct the proofs! We’d probably invent a whole new set of ways of mucking up the page.

I think that Nicodemus understands that Jesus is talking about transformation. (“You people, you have to start over. It has to be transformationally different.”) Most of the Jewish expectations of the dawning of the kingdom talked a lot about the power of the king in transforming the entire order and structure of things and establishing righteousness. It did not talk about being transformed internally, changed from the inside. They didn’t think in those terms.

Now Jesus is promising too much. You can no more be transformed than you can crawl back into your mum’s uterus, come out again, and try again a second time around, hoping that maybe things will be better! But Jesus doesn’t back down. He says, “Very truly I tell you, no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and the Spirit.” What does that mean?

I have to tell you that there have been quite a lot of different suggestions. Some have thought that water refers to baptism, so unless you are baptized and somehow endued with the Spirit, you can’t get in. But Christian baptism has not really been instituted at this stage. At the beginning of chapter 4, the next chapter, Jesus distances himself just a wee bit from baptism. Although people were being baptized in Jesus’ name, it wasn’t Jesus doing it. By and large, it was his disciples. Jesus is at least distancing himself a little bit from the rite that was just beginning to develop.

Others think this is talking about two births. You have to be born of water (the first birth), and then you have to be born of Spirit (the second birth). So water might refer to the amniotic fluid in the sac. We still use the expression of the “water breaking.” Once the water breaks, then the birth follows in due course, whether quickly or slowly, but first of all, there has to be the breaking of the water. That’s natural birth. Then after that comes spiritual birth.

You have to be born twice. First of water, then of Spirit. But in all of the ancient world, I have not found any source in Jewish or Greco-Roman literature that speaks of natural birth as being “born of water.” I’m not sure that anybody would have picked that one up quite that way, for another reason that I’ll give you in about two minutes.

Others have suggested that water is a symbol for semen. So again, you have to be born of water (that is, physical birth), and then you have to have a kind of spiritual life force as well. The same thing has to be said: I have not found any references in ancient literature to being “born of water” as being a reference to male semen.

There’s something more important than that. Compare verse 3 and verse 5 in your Bible. Stick your finger on both verses, and take out the common bits. Now our translations are a bit different, but you’ll get the idea right away no matter what translation we’re using. So verse 3 says, “Jesus replied,” and verse 5 says, “Jesus answered.” That’s the same, so take it away.

“Very truly I tell you” and “Very truly I tell you.” Take it away. That’s the same. Okay? “… no one can see the kingdom of God” in verse 3 and “… no one can enter the kingdom of God” in verse 5. A small change. They’re parallel. There’s a small difference in emphasis. Bracket them out for the time being.

“… without being born again” in verse 3, compared to verse 5: “without being born of the water and the Spirit.” Now you cannot help but see that verse 3’s being born again is parallel to being born of water and the Spirit. In other words, being born again in verse 3 embraces being born of water and the Spirit. Being born of water and the Spirit cannot be two births. The parallelism between verse 3 and verse 5 shows that that being born of water and the Spirit is precisely what is meant by being born again.

Then the final bit of evidence, before we conclude what this means, is from verse 10: “You are Israel’s teacher, and do you not understand these things?” What is it, then, that Jesus expects Nicodemus do have understood? What’s he holding him accountable for? What’s the knowledge base that he has that should have given him a better understanding of what Jesus was talking about? Well, he was an expert in what we call the Old Testament. He was an expert in Jewish Scripture and tradition.

You then ask yourself, “Okay, where does the Old Testament speak of new birth?” The short answer is that it doesn’t, at least not explicitly in those terms. But the Old Testament does bring together water and Spirit quite a number of times. It is always in the context of transformed life. One of the most stunning of these passages is Ezekiel chapter 36, verses 25 and following, where, in the context of the promise of a new covenant, God will come, and he will sprinkle their hearts with clean water and pour out his Spirit upon them.

In other words, the water symbolism is bound up with cleansing. The talk of the Spirit is bound up with power for transformation. It’s as if Jesus is saying, “You will be cleaned up and transformed. That’s the kind of new birth I’m talking about. Nicodemus, you should have understood that because these are your Scriptures.”

Moreover, it’s not just there. You find similar concatenations of water and Spirit elsewhere in the Old Testament and many, many passages that promise transformation from God. Read, for example, what Joel has to say, picked up by the apostle Peter in Acts 2. Sometimes they do so even without talking about water and Spirit.

Nevertheless, the promise of the new covenant in Jeremiah 31, six centuries before Jesus, promises a time when God will write his law on their hearts, and “they will all know me from the least to the greatest.” This is a transformation from within, a notion of inbreaking power that transforms men and women, not just breaks in a new political order, a new Davidic king.

“Nicodemus, you haven’t been focusing on the right things. You cannot really see the kingdom, you cannot really enter it unless you yourself are transformed by this new birth, which is characterized by water and Spirit.” That is, a cleaning up and a powerful, internal transformation. Then Jesus gives two illustrations to unpack it just a wee bit.

1. “Flesh gives birth to flesh, but the Spirit gives birth to spirit. You should not be surprised at my saying, ‘You must be born again.’ ” (Verses 6 and 7)

That is, if you really are going to transform people, they must have a new origin. Pigs give birth to pigs. Snakes give birth (well, through eggs) to snakes. Sea otters give birth to sea otters. Whales give birth to whales. Rhinoceroses give birth to rhinoceroses. Like produces like. We human beings generate more sinful human beings. That’s what we do.

So to transform us, we must have power from God. We must have something from the Spirit. It’s what Paul talks about in 1 Corinthians 2, where he says, “The natural human being does not understand the things of God.” It’s another world. It’s another order. We just don’t grasp those things until the Spirit of God opens our minds and hearts so that we are enabled to see them. “You must be born again.” Then there is another illustration …

2. “The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit.” (Verse 8)

As I’m sure most of you here know, the word for wind in both Greek and Hebrew is also the word for Spirit: ruach in one and pneuma in the other. “The wind [the Spirit] blows …”

So maybe Jesus and Nicodemus are on a street corner in Jerusalem. It’s dark. A little push of wind starts flapping some of the large sycamore leaves that are hanging from the trees, or a little dust ball dances down the street. Jesus says that when you see the effect of this wind, you don’t say, “Oh, there’s a high in the Arabian Peninsula. Is it cyclonic or anticyclonic? Which way is it going? Is this produced by differential heating of the earth’s surface? Or is it caused by something else?” They knew even less about meteorology in those days that we know today!

You watch the sycamore leaf blowing in the tree. You might not have a whole explanation for wind, but you can’t deny the effect. Then Jesus says, “So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit.” What that means is that you may not be able to give a detailed breakdown of the mechanics of new birth, but you can’t deny the effect. I just can’t stress how important that is. We finally come to my first point: what Jesus says the new birth is about.

When people start talking today about conversion, what do they mean? You can convert from Hinduism to Islam, from Islam to Christianity, from Christianity to Islam, from being a secularist to being a Christian, from being a Christian to becoming a secularist. Conversion in that sort of context merely means a change of mind. That’s all it means. It’s a change of mind and, therefore, with it, a change of allegiance.

But in the Bible, that’s not conversion. Conversion entails genuine, God-given, powerfully transforming, miraculous, supernatural interposition. God is doing something. He pours out his Spirit so that people are transformed. Even if you don’t understand the mechanics, you can’t deny the effect.

There are, in churches in America, lots and lots of people who claim to be “born-again” (because they’ve signed a card or gone forward or whatever they’ve done; they’ve been “processed”), but their lives are indistinguishable from the lives of people who aren’t Christians all around … in terms of their vocabulary, their use of time, their goals, what they think about, what they dream about, what they look for in a mate, what they want to do with their pocketbook, and so on.

If they are indistinguishable from any friendly neighborhood pagan, but they’ve been “born again,” then I have to tell them that they haven’t been. Because this text says the new birth is so transforming that you see the effects even if you can’t explain the mechanics. “So it is with everyone who is born again,” Jesus says. Conversion, in the New Testament, though it involves a change of mind, is not merely a change of mind. It is a work of God. It is new birth. That is why Whitefield kept saying, “You must be born again.”

Muslims will tell you that, for them, conversion does not involve a supernatural transformation in the heart or life. What it involves is a decision of will. That’s it. You decide to confess one god, Allah, and Muhammad as his prophet, and to come under certain fundamental rules bound up with what Islam is. That’s a willed thing. In fact, strictly speaking, whether you actually believe this with your whole heart or not is not the first and foremost consideration. The first and foremost consideration is that you make a choice to go in this direction.

It’s true that when you become a Christian, there is a willed choice being made, but it is a willed choice that is, itself, grounded in the transforming work of God. That is conversion. It’s what God is doing. It’s good news about God. “I tell you, Nicodemus …” And I tell you. “… you must be born again. So it is with everyone who is born again.”

Well, this is way beyond Nicodemus, and he asks, “How can these things be?” That is what earns the rebuke of verse 10. In other words, religion (that is, biblical religion from the perspective of the Lord Jesus himself) is not merely one activity or just a matter of making a decision or the like. Rather, it involves a miraculous, supernatural, new origin bound up with the Spirit of God that cleans us up and transforms us.

Out of this comes the change of life that works out in terms of doing good to neighbor, being concerned for justice, and all the rest. Those things are the entailment of new birth. That is, we have a different way of looking at people. We have a different set of priorities. We don’t see suffering in exactly the same way anymore because we’ve been born again. But it starts, not by doing those things; you can do those things without being born again. It starts with being born again. It starts with new birth: this act of God that cleans us up and transforms us.

I know that there is always a danger in talking about salvation and conversion in those terms because then some people, especially those with sensitive consciences, start looking inward. They start saying, “Yes, but have I been transformed enough? Where’s the real evidence that I’ve been transformed? I made a profession of faith. Maybe I’m one of those people who, like those at the end of John 2, trusted in Christ, but Jesus does not commit himself to them because he knows what is in their hearts. He knows that they’re not really genuinely converted at all.

Do I have enough evidence in my life that I can really, truly say I’ve been born again? Maybe I won’t really know until the last day.” So you live all your life in fear. That can happen too. But this passage isn’t over yet. We have a little farther to go before we try to answer that question. For the moment, however, this is what Jesus says about the new birth.

2. Why Jesus could speak so authoritatively about being born again. Verse 11 to 13

Very truly I tell you, we speak of what we know, and we testify to what we have seen, but still you people do not accept our testimony.” Just pause there for a moment. Have you noticed Jesus’ first-person plural? “We speak of what we know …” Why? Is Jesus associating himself with his disciples? “My disciples and I, we speak of what we know.” Read the rest of the chapter, and you discover that the disciples are still pretty clueless.

Then you read the end of the previous chapter, and you see that they are very clueless! Jesus says, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it again.” John comments, “Well, the disciples didn’t have a clue what was going on at the time, but after he had risen from the dead, then they remembered his words, understood the Scriptures a little better, and saw what he was actually talking about.”

At the time, however, they were probably muttering under their breath, “Deep, deep. He’s at it again. More enigmatic instruction. We’ll understand someday. Just press on.” So there’s just no way that it makes any sense whatsoever, in the context, for Jesus to say, “My disciples and I, we know what we’re talking about.

Others of more liberal persuasion say that this proves that John is not being historically accurate. They say that what the we refers is to Jesus and the disciples decades later in the history of the church. That is, “We Christians understand what we are talking about, and you Jews who are still in the synagogues don’t have a clue.” In this view, Jesus associates himself with Christians. What that means, of course, is that this is not historical. That is, John, the writer, has all of his dates wrong. It’s anachronistic. You can’t believe this historical witness.

But one of the things that is very clear in John’s gospel is that he’s constantly making a distinction between what the disciples understood back then and what they understood only later. That is made very, very clear 16 times in John’s gospel. So why you think you should muff it here, I’m not quite sure. He’s very capable of making the distinction between what they understood back then and what they understood only later.

No, I think, once again, John is being wonderfully sensitive. There’s Nicodemus. He approaches Jesus and he says, “Ahem. Rabbi, we know that you have been sent from God because you’re doing pretty spectacular miracles.” Jesus says, “My dear Nicodemus, we know one or two things too, we do.” I think that it is a subtle rebuke, using Nicodemus’s own category, to prick the pompousness of his pretensions.

The evidence for that is that, immediately, then, in verse 12, Jesus reverts to the first-person singular. He uses the first-person plural just long enough to get the point across then takes the knife out. He says, “I have spoken to you of earthly things …” Notice the I now, first-person singular. “… and you do not believe; how then will you believe if I speak of heavenly things?”

Earthly things? The earthly things in question have to be the new birth. That’s all that Jesus has commented about. The new birth itself is an earthly thing. Not that it has its origin on earth, but this is where it takes place. It takes place in our lives here on earth. This is not some highfalutin metaphysical speculation about the nature of the Trinity or something like that. This is what takes place in the lives of ordinary human beings here on earth.

It’s as if Jesus is saying, “I’ve talked to you about that, and you can’t swallow that. Supposing I tried describing for you the glories of the throne room of God? How would you cope with that? You’re finding it so hard to believe this? But you know, Nicodemus, I could tell you about that, but if you can’t believe this, how on earth are you going to believe that? But the reason I could tell you about that is …”

Verse 13: “No one has ever gone into heaven …” That is, to check things out, see what God is like, see what his promises are, get all the correct interpretations of the Bible, figure out what the new birth is, and so on. No one has ever gone into heaven to check it out and then come back and give a report. “… except the one who came from heaven—the Son of Man.”

Do you see what this means? Jesus grounds his entire teaching on the new birth on a claim of unique revelation. Jesus does not present himself as one religious philosopher amongst many. “Well, you know, study some Buddha, and study some Muhammad. Make sure you understand who Krishna is in the Hindu pantheon, and then study a bit of Jesus. We’re all really saying the same things, you understand.” No, he is insisting that his insight into these matters is absolutely and utterly unique because he is the only one who has come from the very presence of God.

What is presupposed is the incarnation of the first chapter, the prologue of John’s gospel. “In the beginning was the Word …” God’s self-expression. “… and this self-expression was with God …” God’s own fellow. “… and this self-expression of God was God.” God’s own self. “The Word became flesh …” He became what he was not. He became a human being. “… and lived for a while, tabernacled amongst us for a while. And we have seen his glory.”

It’s as if Jesus is saying, “Don’t you understand, Nicodemus? No one has been up to heaven to sort of check it out. The reason I can speak so authoritatively about these matters is precisely because I’m the only one who has actually come from heaven.” When you commend Christianity, when you start talking about the gospel, you never advance your case a little better by ducking this revelatory claim.

It is at the heart of it. Sooner or later, people will divide around it. They will see that there is coherence, credibility, honesty, and integrity. They will see that Jesus really is unique, and they will bow before him in worship. Or they will say, “I just don’t believe it. The guy is a megalomaniac. I cannot stand this stuff.” And they will turn and walk away. Crowds will divide around Jesus, around Jesus’ uniqueness, around Jesus’ unique claims to revelatory authority.

I can’t tell you anything finally authoritative about the new birth: how it works, why it works, how it’s grounded, what it does.… I can talk a little bit about my experience, but that is so ethereal … unless I’m actually repeating what Jesus says, who speaks out of a revelatory base. He is from God, one with God, and comes and speaks what he knows.

Our task, at that point, is not to evaluate him but to listen. Once we’ve come to grips with who he is, our task is not to pick and choose what we like about him but to fall before him and say, as Thomas later in the book, “My Lord and my God!” and learn from him.

There are various ways that world religions claim to know something about the divine: mysticism (some personal, immediate contact with God), reason (so that you can sort of reason your way to God), or revelation (God discloses himself to us). Now the Bible certainly wants us to use our reason, and the Bible certainly talks about us knowing God personally, but, at the end of the day, the ground for everything is not our experience of God, nor is it how we’ve reasoned ourselves to God. It is, rather, the way God has disclosed himself to us. It’s a revelatory claim.

3. How Jesus brings about this new birth

Verse 14 and 15: “Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him.” What this presupposes, of course, is that Jesus knows that Nicodemus (and John knows that his readers) will remember the Old Testament story in question.

It’s not too surprising when Nicodemus has memorized the whole thing, but for John to recount this so briefly, without giving more of the details, shows that his envisaged readers were people who understood something of the Old Testament as well. They knew the basic storyline. This, of course, is a summary of what takes place in Numbers 21:4–9. Let me read that paragraph.

“They …” That is, the ancient Israelites, now having escaped from Egypt and now in the desert years before they enter the Promised Land. “… traveled from Mount Hor along the route to the Red Sea, to go around Edom. But the people grew impatient on the way; they spoke against God and against Moses, and said, ‘Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? There is no bread! There is no water! And we detest this miserable food!’ Then the Lord sent venomous snakes among them. The snakes bit the people, and many Israelites died.

The people came to Moses and said, ‘We sinned when we spoke against the Lord and against you. Pray that the Lord will take the snakes away from us.’ So Moses prayed for the people. The Lord said to Moses, ‘Make a snake and put it up on a pole; anyone who is bitten can look at it and live.’ So Moses made a bronze snake and put it up on a pole. Then when anyone was bitten by a snake and looked at the bronze snake, they lived.” That’s it. That’s the whole account.

Jesus, now, to ground what he says about the new birth, says (verses 14 and 15), “Just as Moses lifted up the snake in the wilderness, so the Son of Man must be lifted up, that everyone who believes may have eternal life in him.” What is going on? Because on the face of it, that’s not the first Old Testament text that I would think about. It’s not where my mind would gravitate if I were suddenly trying to explain the grounding of the new birth. Is it where you would go?

Moreover, the story is a bit odd, isn’t it? Try and explain that to your secular friends! A bronze snake in the desert; look at it, and you escape the venom from a snakebite? Bizarre! More supernatural stuff. It is, plainly, meant to be a supernatural account or an account of the supernatural. But then pause for a minute and read sympathetically. Just read sympathetically. What is it that Jesus sees as the parallel between what happened then and what happens now? What is it that Jesus is getting at?

In the Old Testament, God had released the people from slavery and bondage, and he was taking them to the Promised Land. He provided them with the food that they needed. He gave them manna and, in due course, he gave them quail. They had enough to eat. He guaranteed that their shoes didn’t wear out. In this semi-arid region, from time to time, God provided water miraculously. They did have enough. It wasn’t an ideal situation, but they were no longer slaves and were on their way to the Promised Land.

But at various points, the people just rebelled against this. They started dreaming nostalgically that at least when they in Egypt, they might have been slaves, but they could get their garlic! They could actually have herbs a little more often. It wasn’t just manna, this disgusting food. “I’d like to have some garlic with my manna, you know?” Pretty soon, it builds up into a full-blown anarchic rebellion against not only Moses but against God.

It’s part of the general biblical pattern of how quickly we become disaffected with God. We don’t want to suffer anything, don’t want to endure anything, and don’t want to persevere. We’re like little kids who live only in the “Now!” Try to explain to a 3-1/2-year-old, “Dinner is in 10 minutes; just wait.” “Now!”

You cannot explain any notion of delayed gratification to a 3-1/2-year-old. “Now!” The Israelites are like that in the desert. Eventually, their childishness, their criticism of Moses and of God just becomes anarchic rebellion once more. “We know better than God.” God says, “All right, do it your way,” and he sends them the snakes to punish them.

Eventually, the people cry for help. The help that God provides is instruction to Moses to cast a figure of a snake in bronze and stick it up on a pole. All you had to do to be released from the poisonous venom was to look at that God-ordained snake. That’s it. God provided the judgment, and God provides a solution.

It’s not as if you had to go out and do 50 push-ups under the barking order of a Marine sergeant. It’s not as if you had to compete a half-marathon to prove that you were actually repentant, that you were going to be more disciplined. It’s not as if you had to take some whips and start flagellation. No, you looked at the provision that God himself had made, and the result was, frankly, a flat-out miracle.

Now you look at what’s taking place in Nicodemus’s time. “What people need,” Jesus says, “is this transformation from God. They need new birth. That’s what gives eternal life.” Do you see how verses 14 and 15 run toward eternal life? New birth starts a course of things that issue in eternal life. That’s what it produces. The one who has eternal life looks to another being put up on a pole.

I’ve said before that John loves to speak allusively of things. He uses this expression lifted up four times in his gospel, and in every occasion, it’s talking about Jesus finally being lifted up in crucifixion. He’s not stoned to death. He’s not decapitated. He is lifted up, the provision that God has made. People turn to him and, instead of death, gain life: eternal life out of what God has done. It is, quite frankly, a flat-out miracle. It’s new birth. That’s the parallel. It’s profound.

But we rip through those Old Testament texts, note that this is a bit of a strange miracle, and press on to something that is a little nicer, like, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” We don’t see what’s actually going on: God providing the only answer there is. It’s received simply by looking to it and receiving what God has provided.

So this new birth that Jesus is talking about comes about, finally, not by screwing up your stomach muscles to believe what you don’t really believe, not by turning over a new leaf, and not by signing a pledge. No, in the first instance, it is grounded in what God has done. He has sent his Son to be lifted up on another pole: a wretched cross outside the city of Jerusalem on a disgusting hill called the place of the skull. Those who look to Jesus there have eternal life, as they put their faith in him.

4. Why Jesus was sent to bring about this new birth

Verse 16. “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” This is God’s provision, and it’s a provision that was granted out of God’s love for the world.

We need to think about this notion of world. What leaps to your mind when you hear the word world? When you say, “God so loved the world,” does that mean God’s love must be so wonderful because God is so big, big enough to love this whole world? But in John’s thinking, the word world is not really associated with bigness.

In two or three places, it’s a neutral word that doesn’t mean an awful lot. For example, in the last two verses of John’s gospel, we’re told that it’s a big place that holds a lot of books. We’re told that if everything that Jesus had done had been written into books, then the world itself would not be big enough to contain them. Fair enough. It’s a big place that holds a lot of books. I rather like that usage, myself.

But the word world shows up almost a hundred times in John’s gospel, and almost always it means the moral, sentient order in rebellion against God. God made the world, but the world did not recognize him. The world is the bad place. When I was a boy, in Christian circles we still spoke about worldliness. We don’t talk much about worldliness anymore, but when I was a boy we did.

“Never drink, smoke, swear, or chew, and never go out with girls that do.” Now that wasn’t the sum of all worldliness, but it was pretty close! Today we don’t talk about worldliness anymore, and in any case, if that’s what worldliness is, it’s pretty shallow, besides being pretty male-oriented too.

No, worldliness is much more profound than that. Worldliness, in John’s usage, is the entire moral order against God. It is men and women doing their own thing independently of him. So already in the prologue, in the opening verses, John writes, “He came to the world that he himself had made, but his own world did not recognize him. He came to his own people, and his own people did not recognize him.” That’s the world. Do you see? But “God so loved this world that he gave his Son.”

Picture John and Susan, walking along one of the beaches of California. It’s a warm evening. They’ve kicked off their sandals. They’re walking hand in hand down the beach. There’s a lovely breeze coming in off the Pacific, ruffling their hair. The sun is setting in the west. John turns to Sue, and he says, “Sue, I love you.” What does he mean?

It could mean quite a lot of things. It could mean nothing more than that his hormones are hopping, and he wants to go to bed with her forthwith. It could be. But if we assume, for a moment, that there’s a modicum of accountability and decency, let alone Christian principle, in the chap, then the least he means is something like this:

“Susan, in my eyes, you’re absolutely wonderful. The way the sun glints in your hair, the beauty of your eyes.… Your smile just captures my heart absolutely. Your personality is wonderful. I love being with you. I just feel so free and complete when I’m with you. You’re absolutely wonderful. I can’t imagine life without you.” In other words, when he says, “I love you,” in part, isn’t he saying, “I find you lovable”?

He does not mean, “Susan, quite frankly, your halitosis would scare off a herd of rampaging elephants. Your hair is so greasy that you could oil an eighteen-wheeler. Your knees remind me of a crippled camel. You have the personality of Genghis Khan. But I love you! I love you!” That’s not what he means, is it?

Now our text says, “God so loved the world.” What does he mean? Does he mean, “World, world, you’re so lovely in my eyes? I cannot imagine eternity without you. The wit with which you address me, the glory of your guitar playing.… When you worship me, I just feel so complete. World, world, I love you, and that means that you’re very lovable.”

I’ve read some Christian psychology books that argue exactly that way. The world must be really wonderful because God loves us. Good grief! That’s exactly wrong! Morally speaking, the world is the world of the crippled camel knees, the personality of Genghis Khan, the greasy hair, and the halitosis! Morally speaking, that’s who we are, and God loves us anyway! Not as a mark of how wonderful we are but of the kind of God he is.

“God so loved the world that he gave …” His second best? No. John’s gospel keeps reiterating that in eternity past, the Father loved the Son, and the Son loved the Father. There is a unity of love in the Godhead that we can barely glimpse. It surfaces again in the great High Priestly Prayer of John 17. It shows up in John 5 and John 3 and John 14. It’s spectacular.

God, the Father, loved the Son from all eternity and loved this disgusting, rebellious, anarchic, halitosis world so much that he gave the Son he loved. That’s why Jesus becomes the figure lifted up on the pole. It’s not just that Jesus loves us. His Father loves us and sends his Son, and the Son is committed to doing his Father’s will. That’s why we experience new birth when we turn to him. It’s all grounded in what God has done. This is the gospel. It’s the good news of what God has done. That’s what we’re announcing. That’s what we’re proclaiming.

“… that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” For the alternative, as the last verse in the chapter makes clear, is the judgment, the wrath under which we already rest. “Whoever believes in the Son has eternal life, but whoever rejects the Son will not see life, for God’s wrath remains on him.” Listen, you must be born again. Let us pray.

Open our eyes, Lord God, to see the glorious, exclusive self-sufficiency of our dear Lord Jesus, how he alone can speak so authoritatively in human context because he comes from above. He knows the throne room of God. From eternity past, he was God’s own fellow and God’s own self. In the fullness of time, he became flesh and lived for a while among us.

We thank you that he came not only to instruct but to be lifted up on a pole … our substitute, our death, our curse … so that all who believe in him may be saved. We thank you that this transforming, cleaning, powerful new birth is grounded in what he has done. We ask, Lord God, for the clear-sighted spiritual vision to see Christ afresh and to truly, continually believe. For Jesus’ sake, amen.

Join The Carson Center mailing list

The Carson Center for Theological Renewal seeks to bring about spiritual renewal around the world by providing excellent theological resources for the whole church—for anyone called to teach and anyone who wants to study the Bible. The Center helps Bible study leaders and small-group facilitators teach God’s Word, so they can answer tough questions on the spot with a quick search on their smartphone.

Click the button below to sign up for updates and announcements from The Carson Center.

Join the mailing list »Don Carson (BS, McGill University; MDiv, Central Baptist Seminary, Toronto; PhD, University of Cambridge) is emeritus professor of New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois, and cofounder (retired) of The Gospel Coalition. He has edited and authored numerous books. He and his wife, Joy, have two children.