Whenever the topic of George Whitefield comes up in my classes, I always have to tell the students, “I know it looks like you’d pronounce his last name White-field, but it is pronounced Whit-field.” Therein lies the reason why Whitefield, the greatest evangelist of the 18th century, also has one of the most misspelled names in history. In one of the odd accidents of English pronunciation, Whitefield’s name was not pronounced the way it is spelled. Thus from the beginning of his public career, people have been misspelling Whitefield’s name as “Whitfield.”

I see it all the time on social media. On Twitter, there are on average multiple tweets per day where his name is misspelled. (Figuring this out is made slower by the fact that one of America’s most prominent quarterback trainers is named—you guessed it—George Whitfield. I do not know if he’s named for the evangelist.)

One of the first misspellings of Whitefield’s name came in one of his first published sermons. In 1737 in London, a publisher produced an edition of what would become one of his signature sermons, The Nature and Necessity of the New Birth, but misspelled his last name. After that, most publishers were clued in to the correct spelling as he became arguably the most famous man in Britain and America during the mid-1700s.

But misspellings continued to pop up occasionally. Sometimes the name would be spelled correctly on the title page but wrongly within a publication. A 1771 Boston edition of John Wesley’s memorial sermon for Whitefield misspelled the name on the title page. (Ironically, Whitefield died in the Boston area in 1770. When word arrived in London, Wesley gave a memorial sermon at Whitefield’s Tottenham Court Road chapel, and the text of it made its way back across the Atlantic, where it was published in Boston, with Whitefield’s name misspelled.)

It appears that misspellings of his name became more common after Whitefield’s death in 1770. They started to appear in some significant publications, such as Olaudah Equiano’s remarkable slave narrative of 1789. There was also a different person named George Whitfield who worked in John Wesley’s book business and who appeared in Wesley’s will, which could have added to the confusion.

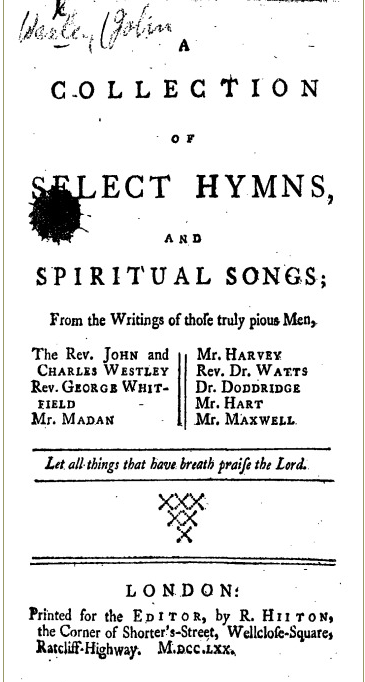

Another important reason for the chronic misspellings of Whitefield’s name in print was that spelling and editorial standards were, in general, lower in the 18th century than today. Thus a lot of misspellings of names and words showed up in a variety of publications. A notable accomplishment on this front was a hymnal (see image) that managed to misspell both Whitefield’s and the Wesleys’ names on the title page!

Learn more about Whitefield (hopefully with his name spelled correctly in every instance) in my 2014 Yale University Press biography of him.