Last month, Jonathan Haidt—professor of social psychology at New York University’s Stern School of Business, ethnically Jewish, politically left-leaning, and religiously atheist—stood on the main stage of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU) conference.

“I was born to be the sort of person who is opposed to your mission,” he told about 1,200 college leaders.

“Within two years of my bar mitzvah, I started calling myself an atheist. And not just an atheist, but one of those atheists that sees religion—Christianity especially—as the opponent, as the enemy, because they believe creationism and we scientists believe in evolution.”

Several things changed his mind, Haidt said. Not to convert to Christianity—he’s still an atheist—but to drop his hostility toward it.

“I got my first teaching position at the University of Virginia,” he told the CCCU. UVA draws students from all over the country, but especially from the western and southern parts of the state.

“I had never met evangelical Christians, growing up in New York and going to Ivy League schools,” Haidt said. (He received a BA from Yale University and a PhD from the UVA, then did postdoctoral work at the University of Chicago.) “Of course they were there, but they weren’t as ‘out’ as they were at UVA.”

Haidt’s Christian students “radiated a kind of sweetness, a kind of warmth and gentleness and humility that I hadn’t seen before,” he said. “It was really lovely.”

He saw the same “warmth and openness and love” from evangelical churches he visited as part of a class on moral communities. “It was really beautiful, and it touched my heart. And when your heart is open, then your mind is open.”

As one who studies morality, Haidt was also impressed with the Bible (“among the richest repositories of psychological wisdom ever assembled”) and with the actions of Christians (“religious conservative Americans are . . . more generous with their time and money [than secular Americans]”).

“I started realizing that the scientific community at that time . . . was really underestimating and misunderstanding religion,” he said.

Haidt’s charming introduction softened the room, but his academic work got him the invitation. Haidt has been earning accolades in the public square for some time—he was named one of the top 100 global thinkers by Foreign Policy in 2012 and one of the top 30 world thinkers by the British Prospect Magazine in 2013.

He’s been studying and writing about morality and religion since graduate school, penning The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom in 2006 and The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion in 2012.

It was The Righteous Mind—“the most important book in years,” Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission president Russell Moore once tweeted —that caught the CCCU’s attention. Haidt’s book is laced with evolutionary explanations, but it’s not hard to see the design in what he has discovered.

The book is laid out in three parts. First, Haidt argues that people make most of their decisions emotionally rather than logically. Second, he posits that political conservatives have twice as many foundations for morality (six) as liberals (three). And third, he explains the “hive mentality,” or the way humans operate optimally in groups. (That’s why religion—a prime way that people belong to one another—has been good for society, he writes.)

For these reasons, Haidt explains, politically liberal and conservative people can talk right past each other, each amazed and appalled at the “immorality” of the other.

The Righteous Mind debuted at number six on The New York Times bestseller list, and got good reviews from almost everybody. “Liberals like it!” exclaims the book’s website, which includes segments of 32 reviews. “Conservatives like it! Libertarians like it! The British Right likes it! The British Left likes it! Non-partisans like it! Scientists like it! Religious intellectuals are . . . interested in the book!”

And it’s true that Christians have been a bit slower to warm up to Haidt’s ideas.

“Jonathan Haidt is an unlikely source of inspiration for evangelical Christians, given the fact he’s a secular Jew and a political centrist with certainly some liberal inclinations,” said TGC editorial director Collin Hansen. “But for me, at least, his message came at exactly the right time.” (Listen to Hansen’s 2012 interview with Haidt.)

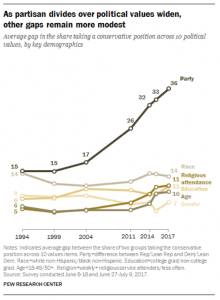

Since then partisan differences in America have only widened, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. And President Donald Trump, it seems, is more of an effect than a cause. The growing gap on a variety of values—government regulation of business, welfare, corporate profits, race issues, immigration, homosexuality, environmental regulations, and military strength—was happening long before 2016.

That change is making politics a lot less friendly. Almost half of both Democrats (44 percent) and Republicans (45 percent) view the other party “very unfavorably,” a “dramatic” increase since the 1990s, Pew stated.

The 2016 election turned the media spotlight onto that gap, and also onto white evangelicals, who are struggling with their own partisan conflict. While most white evangelicals have been Trump’s staunch allies, many leaders have been outspokenly opposed.

“It’s been a challenge in the last decade to see divisions within the church as well as within the broader political conservative world, not to mention disagreements we have with each other across the political aisle or theological spectrum,” Hansen said.

To have Haidt’s window into that division is a gift, he said.

“In the Reformed tradition, we have an appreciation for all truth as God’s truth, and a belief that common grace can help even people who are not regenerate to be able to help advance some truth,” Hansen said. “And I think that’s the case with Haidt.”

Haidt uses “so many interdisciplinary strands of research, from biology to psychology,” to provide a convincing, holistic approach, said Wheaton College political science professor Amy Black. “It was revealing to me about human nature.”

“It’s important for both secular and religious people to read what he has to say,” said Redeemer City to City chairman and TGC vice president Tim Keller. “Jonathan Haidt is a secular thinker with a deep appreciation for religion and a fair-minded assessment of faith’s importance in society.”

Disordered Affections

Meeting evangelical students wasn’t the only experience that changed Haidt’s views on religion.

In the early ’90s, he spent three months in India on a Fulbright fellowship, watching women serve men in silence in a “sex-segregated, hierarchically stratified, devoutly religious society.”

As a 29-year-old liberal atheist, he struggled with this culture, but only for a few weeks.

“I liked these people who were hosting me, helping me, and teaching me,” he wrote in The Righteous Mind. “Wherever I went, people were kind to me. And when you’re grateful to people, it’s easier to adopt their perspective.”

Haidt began to open to their interpretation of reality—where men weren’t oppressors of helpless female victims but all were part of an interdependent family, where “honoring elders, gods, and guests, protecting subordinates, and fulfilling one’s role-based duties were more important” than personal autonomy and equality.

In this, Haidt is his own example of the “rider and elephant” analogy, which he introduces in The Happiness Hypothesis. If our emotions are like an elephant, reason is a rider perched on top. Most of our decisions are gut reactions, our intuition as strong and unwieldy as an elephant. Our reasoning comes later to justify our decisions, and only through hard work can the rider get the elephant to switch directions.

Haidt isn’t the first to argue that emotions usually trump reasoning.

“I find [Haidt’s work] to resonate strongly with what we see in the Gospels themselves, of how Jesus relates to people, of a Pauline understanding of the will and the affections,” Hansen said. “We’re not primarily rational beings who array our arguments against one another until one side or another prevails, but we are profoundly driven by our emotions, our passions, our affections, and ultimately our intuitions.”

Those intuitions are “powerfully shaped by our experiences, our locations, our tribal instincts, and which audiences we want to play to and be accepted by,” Hansen said. “So if you go into pastoral counseling, and evangelistic conversation, or an apologetic defense of the faith and assume all you need to do is prevail in the battle of ideas with this other person, you’re not likely to succeed.”

But people try it all the time, both in the religious and political spheres. That’s because giving emotions their due has fallen out of favor, a casualty of the Enlightenment and the growing estimation of scientific logic and reasoning.

Too far out of favor, Haidt would say. He and others have “shifted the framework,” said Wheaton College political science professor Kristin Garrett. She changed her dissertation topic to morality and politics in part because of The Righteous Mind, and teaches Haidt’s work to her students at Wheaton.

She’s trying to show them that Christians should change how they argue—not to manipulate, but to be more strategic, she said. “You can make the same argument in a different way that sheds light on a lot of areas.” (For example, showing an ultrasound to a pregnant mother could make the same pro-life argument in a far more effective way than a list of developmental milestones.)

“We should also think about the ways we’re shaping our minds and habituating our virtues, because our heart reactions matter,” she said. “We need to recognize not just the importance of reason and thought but also the deeper things as well—our visceral, heart reactions.”

Garrett does this by posting Bible verses around her home and office, being mindful of the music she listens to, and praying—in short, by ordering her affections.

But as we’re making our gut moral judgments on issues, so is everyone else.

Moral Foundations

“[A]n obsession with righteousness . . . is the normal human condition,” Haidt writes. He told the CCCU, “Human beings evolved to be religious. It’s in our nature. . . . There is a God-shaped hole in the heart of each man.”

It’s a remarkable, even Augustinian statement for an academic atheist.

“If there is a God-shaped hole in everyone’s heart, regardless of how it came about, then it matters how that hole gets filled,” he told the CCCU. “If you fill it with a community that values service and decency and responsibility and caring for your family and caring for others . . . then things will go well for those people and for the community and for the country.”

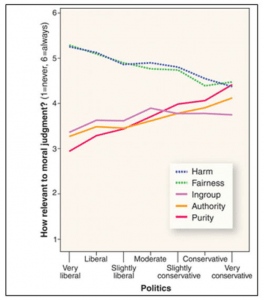

He’s alluding to his moral foundations theory—or the six different values he believes are common across time and cultures:

- Care/harm (We want to help those who are hurting, and punish those who are cruel.)

- Fairness/cheating (We want to work with people who won’t exploit us, and shun cheaters.)

- Liberty/oppression (We are sensitive to—and don’t like—attempts to bully or dominate.)

- Loyalty/betrayal (We reward those who are trustworthy, and avoid or hurt those who betray us.)

- Authority/subversion (We keep order by forming social hierarchies.)

- Sanctity/degradation (We give certain objects—say, a crucifix or a communion chalice—what Haidt calls “irrational and extreme value,” which serves to bind us together socially.)

Using multiple surveys, Haidt found that political liberals don’t give much credence to the last three.

Even in the first two, which conservatives and liberals both hold highly, the interpretations cause fractures. While both parties prize care, they disagree on crime (Should we focus on rehabilitating criminals or on protecting victims?) and abortion (Do we prioritize the mother or the child?). And while both prize fairness, liberals tend to value a fair division of resources, while conservatives value a fair opportunity to earn those resources.

No wonder it feels like the right and left are talking past each other.

“American politics is set up perfectly for this battle of self-righteousness from the left and the right,” Hansen said. “One thing that’s really helpful to remember is that Christians are not the only people with moral convictions. We cannot treat our neighbors as if they are amoral, in part because our neighbors believe us to be immoral.”

The #MeToo movement is a clear indication that our culture is not becoming less moral, but prioritizing differently, he said. “Haidt helps us to recognize that we can’t be content to touch on one or two moral realms we find compelling. We must press deeper into empathetic understanding of others to realize there are other realms of reality we often underplayed or ignored or even acted against.

“For Christians, that means driving relentlessly into the Scriptures to encounter the full moral spectrum of the perfect God-man, Jesus Christ,” he said. Hansen’s 2015 book, Blind Spots: Becoming a Courageous, Compassionate, and Commissioned Church, was inspired in part by Haidt.

Haidt’s reflections also show the importance of civility, Black said. That’s really important as followers of Christ, “who want to treat everyone as people made in the image of God. We don’t have to share their views, but we need to take them seriously and respect where they’re coming from.”

But listening to one another and being kind, while helpful, doesn’t completely solve the difficulty between liberals and conservatives. Because each side is fighting not just for its values, but also for its tribe.

Created for Community

“Hiving [living in community] comes naturally, easily, and joyfully to us,” Haidt wrote in The Righteous Mind.

But drawing lines to create inclusion also creates exclusion—being close friends with some people means you aren’t close with others, joining one church means you aren’t a member elsewhere, living in one country means you aren’t a citizen of another.

And that “we are not them” reality means our gut reactions—our elephants—are always leaning toward our community and away from others. So when a political or theological issue crops up—say, the environment, or immigration, or infant baptism—we’re wired to agree with our clan right off the bat, and then look for reasons to support that decision. (Alan Jacobs also explores this theme in his recent book How to Think: A Survival Guide for a World at Odds [20 quotes | interview].)

That realization “has been extremely helpful for me—especially during recent political turmoil—to understand why people so easily change their minds about individual characters or policy positions or ideological priorities,” Hansen said. “People are not primarily rational actors basing decisions off intellectual convictions, but in fact they have deep tribal instincts formed in an essential dichotomy where we find our own virtue and righteousness in condemning another group.”

This message caught the attention of Biola University president Barry Corey. Over the last few years, he and other CCCU leaders have been advocating to the California legislature that faith-based colleges should not be forced to change their standards on sexual identity, such as housing based on biological gender and standards on marriage as between man and a woman.

“As we’re going through a lot of the dynamics in California, I realized that I needed to spend more time with influencers outside of our circles who could help us understand what we were doing and how we could do things better,” Corey said.

One of those people is Evan Low, chair of the LGBT caucus in the state assembly. “How can we do things better?” Corey asked Low. “We aren’t changing our core, but we’ve probably made some mistakes along the way. How can we do better?”

The two visited each other’s work places multiple times, eventually coauthoring a piece in The Washington Post on their unlikely friendship.

Haidt is another advocate, Corey said. (The two met face-to-face a year ago, making it the first time Haidt sat down with the head of a Christian organization.) “His research bears out that religious organizations are actually doing good for our society. Instead of graduating bigots, we’re graduating people who make a contribution to society for the good.”

Haidt is “increasingly becoming one of our nation’s public intellectuals,” Corey said. “He is trusted academically. . . . He’s an unlikely ally, but he’s been a great ally.”

Be a Bridge

CCCU president Shirley Hoogstra is also looking to Haidt to be a bridge.

“It’s one thing for Christians to say, ‘Boy, Christian higher education is really a valuable asset to the democracy,’” she said. “It’s another thing for persons who are not likely endorsers to say, ‘Hey, I’ve studied this from outside of the Christian commitment perspective, and I’ve come to my own objective belief that Christian higher education—or religion broadly—is very valuable to society.’”

When she asked Haidt if he’d consider speaking at the conference, he was eager to accommodate.

“He asked me, ‘How can I help your people?’” she said.

So she asked him to teach Christian college leaders how to be better communicators with those outside of the faith, just like Corey is trying to do.

“If we want to be the very best at executing on the Great Commandment and the Great Commission, we then have to equip ourselves with our best possible tools,” Hoogstra said. “And understanding how thoughtful non-Christians think about the things we know are important helps us be better communicators.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.