This is part of TGC’s 2020 Read the Bible initiative, encouraging Christians and churches to read together through God’s Word in a year. Subscribe to our daily newsletter and podcast (Apple | RSS | Stitcher), and join our Facebook group.

Is the Trinity in Genesis 1? The answer is a straightforward “yes.” Because God is Father, Son, and Spirit yesterday, today, and forever, the holy Trinity is present on every page of holy Scripture, including Genesis 1.

Though affirming the presence of the Trinity on every page of Scripture is easy, discerning the mode of the Trinity’s presence in various passages of Scripture is more complicated. If older readers of Genesis 1 were more likely to fall prey to overinterpretation (seeing more of the Trinity than a particular passage attests), contemporary readers are more likely to fall prey to underinterpretation (seeing less of the Trinity than a particular passage attests).

Hidden Presence in the Old Testament

We begin with the larger question of how the Trinity is present in the Old Testament. According to Lutheran theologian Johann Gerhard, the Trinity is present in Genesis 1 “in a manner of revelation appropriate to that time.”

The self-revelation of the Trinity in Scripture unfolds according to a twofold economy. There is that which comes before Jesus’s appearance in the flesh (the self-revelation of the Trinity in the Old Testament) and that which comes after Jesus’s appearance in the flesh (the self-revelation of the Trinity in the New Testament). The contrast between these two forms of revelation is not absolute. It’s not that the Trinity is absent in the Old Testament and present in the New Testament. The contrast is relative. Both testaments are modes of the Trinity’s presence, but they are different modes of the Trinity’s presence. The Trinity is “hidden” in the Old Testament and “manifest” in the New.

The presence of the Trinity in the Old Testament, like a treasure hidden in a field (Matt. 13:44; Col. 2:2–3), is a “hidden presence,” one we can only fully appreciate in light of the Trinity’s “manifest presence” in the New.

Hidden Presence in Genesis 1

With this clarification in place, we’re better prepared to address our question: how is the Trinity present in Genesis 1 “in a manner of revelation appropriate to that time”? Genesis 1 exhibits at least three traces of the Trinity’s hidden presence. These traces provide essential building blocks for the full edifice of Trinitarian revelation manifest in the New Testament.

1. Genesis 1 exhibits several instances of subject-verb disagreement.

In Genesis 1:1, the plural noun “Elohim” (“God” in the ESV) is joined with the singular verb “created”: “In the beginning, [Elohim] created the heavens and the earth.” The pattern is repeated in Genesis 1:27: “So [Elohim] created man in his own image, in the image of [Elohim] he created him; male and female he created them.”

These examples of subject-verb disagreement seem to be intentional on the part of the author. What is he emphasizing? That God alone created all things by means of his singular agency. Creation wasn’t the work of a committee of heavenly beings partnering together. God alone created heaven and earth, without any guides (Isa. 40:13–14) or helpers (Isa. 44:24; Jer. 10:12; 27:5).

Creation wasn’t the work of a committee of heavenly beings.

In emphasizing this point, Genesis 1 provides the first and fundamental building block of trinitarian theology: monotheism. One God created all things, rules all things, and directs all things to himself. Apart from monotheism, belief in the Trinity would be a form of polytheism. Only in the context of monotheism is faith in the Trinity faith in one God in three persons.

2. Genesis 1 includes God’s Word and Spirit within God’s singular agency.

The preceding examples teach us that God alone created heaven and earth. They also help us appreciate the place of God’s Word and Spirit within God’s work of creating.

According to Genesis 1, God’s Word and Spirit are the means whereby God produces, forms, and fills all things. God speaks creatures into existence (Gen. 1:3, 6, 9, 11, 14, 20, 24, 26). God names the various creatures he brings into existence (Gen. 1:5, 8, 10). And God blesses the creatures he brings into existence (Gen. 1:22, 28). Along with God’s speech, God’s Spirit is also active in the work of creation, hovering like a mother bird (Gen. 1:2; cf. Deut. 32:11) over the unformed, unfilled world God produced, ready to endow it with life, energy, intelligence, and fullness by means of his life-giving presence (Ex. 31:3; 35:31; Num. 24:2).

In identifying God’s Word and Spirit as the means whereby God produces, forms, and fills all things, Genesis 1 includes God’s Word and Spirit within God’s singular agency. To say that God creates by his Word and Spirit is another way of saying that God creates by himself and not by the agency of another (Ps. 33:6–9; John 1:3; Rom. 11:36; 1 Cor. 8:6; Col. 1:16; Heb. 1:2).

Whatever distinctions Scripture later reveals between Elohim, his Word, and his Spirit, they should not be taken as distinctions between the one God and something that is not God. They should be taken as distinctions within the one God himself.

Genesis 1 doesn’t yet indicate the full significance that the names “Word” and “Spirit” will have for trinitarian theology. The full significance of these names only comes with the appearance of the Word made flesh and the outpouring of the Spirit at Pentecost. Nevertheless, by including God’s Word and Spirit within God’s singular agency, Genesis 1 puts another fundamental building block of trinitarian theology in place. Whatever distinctions Scripture later reveals between Elohim, his Word, and his Spirit, they should not be taken as distinctions between the one God and something that is not God. They should be taken as distinctions within the one God himself.

3. What about those plurals?

As noted above, Genesis 1 repeatedly identifies God by the plural noun “Elohim.” Some biblical commentators have taken this plural noun as an indication of God’s tripersonal fullness. Still others have taken God’s plural self-address in Genesis 1:26 (“Let us make man in our image, after our likeness”) as an indication that the work of creation is the work of one God in three persons. Are these plural forms also signs of the Trinity’s hidden presence? Let’s focus on Genesis 1:26.

God’s plural self-address in Genesis 1:26 is sometimes explained as an example of the so-called “royal we,” an idiomatic expression whereby a king addresses himself in plural form. Others see it as an example of God addressing the heavenly assembly of angels (Job 1:6; 2:1). Both explanations are unlikely. The first lacks evidence of being an idiomatic expression in the Ancient Near East. The second contradicts the overarching message of Genesis 1 and Scripture as a whole. When it comes to God’s work of creating, God does not enlist the help of angels, which at best serve as an accompanying chorus (Job 38:7). God alone acts by means of his singular, sovereign agency: “I am the LORD, who made all things, who alone stretched out the heavens, who spread out the earth by myself” (Isa. 44:24).

What, then, should we make of the riddle of God’s plural self-address in Genesis 1:26? As Robert Jenson somewhere observes, God’s Word and Spirit are the only candidates Genesis 1 actually presents as potential objects of God’s plural self-address in Genesis 1:26. This observation notwithstanding, a conclusive judgment remains difficult to reach.

The difficulty of arriving at conclusive judgments when interpreting Old Testament revelation of the Trinity should not surprise us—and need not bother us—if we are sensitive to the twofold economy of scriptural revelation of the Trinity. The riddles of Old Testament revelation of the Trinity are only resolved by New Testament revelation of the Trinity.

Genesis 1 Sets the Stage

Traces of the Trinity’s presence in the Old Testament provide precious building blocks for the full edifice of trinitarian revelation that follows in the New. Genesis 1 introduces us to the main character of the scriptural drama: the one God who rules all things by his Word and Spirit. Genesis 1 sets the stage on which the scriptural drama unfolds: the world produced, formed, and filled by the triune God. And Genesis 1 introduces us to the main object of the triune God’s sovereign self-commitment: the creature made in God’s image.

In doing so, Genesis 1 serves the main purpose of holy Scripture, which is to promote union and communion between the holy Trinity and the people created, redeemed, and perfected for himself.

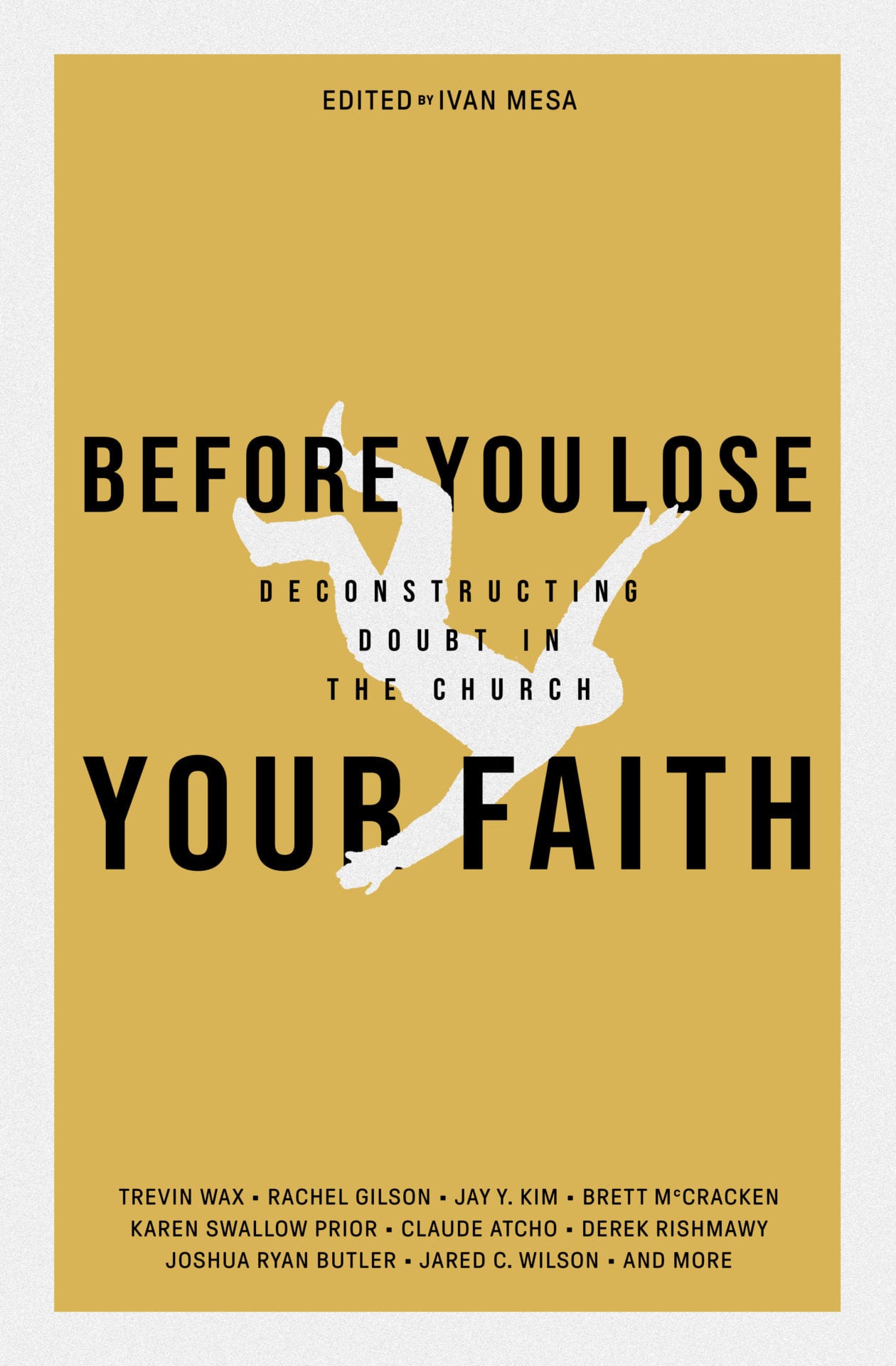

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!