“Send me 100 men skilled in your religion,” Kublai Khan wrote to the pope about 700 years ago. If they were convincing, he said, “I shall be baptized, and then all my barons and great men, and then their subjects. And so there will be more Christians here than there are in your parts.”

But Pope Gregory X, unable to see the future, only sent two. Neither made it Khan, whose territory at that point stretched over one-fifth of the globe’s inhabited land.

That was the “greatest missed opportunity in Christian history,” David Barrett and Todd Johnson wrote in World Christian Trends.

Khan was also interested in Buddhism, and Tibet was a lot closer than Rome. By the end of the 13th century, Khan had translated Buddhist teachings into Mongolian, restored and built Buddhist monasteries, and appointed a Buddhist to the new position of “state preacher.”

Today, Buddhism is Mongolia’s most-practiced religion (55 percent, according to Pew Research Center), followed by the unaffiliated (36 percent) and a smattering of Muslims and folk religions.

About 2 percent of the country’s nearly 3 million people are Christian, which seems small until you consider that when Mongolia opened up after communism in 1990, it was statistically zero..jpg)

Mongolian Christians are slippery to count; estimates have ranged as high as 85,000. But the best guess—landed on the most often, including by the national census—seems to be closer to 40,000. When the Mongolian Evangelical Alliance (MEA) trimmed off the non-evangelicals—like the Russian Orthodox and Roman Catholic—it came up with 30,000 evangelical Christians. There are around 500 or 600 churches, most of them members of the Mongolian Evangelical Alliance, and multiple Bible schools and seminaries.

“Many, many people heard the gospel, and there was an explosion that happened,” said Peter Station, a Southern Baptist worker in Mongolia who asked to use a pseudonym. “So much so, that it was said that it was easier to count Mongolia’s sheep than its Christians.”

And for the most part, those Christians are being trained well. Observers point to the solid theology of early missionaries, along with education and a tight rein on Christian media, for helping Mongolian Christians largely avoid the tendency toward prosperity gospel that other countries with similar characteristics—new to the gospel and sitting on a history of spiritualism—have fallen into.

They’re also eager to share the gospel. Mongolia has sent out more than 20 long-term and numerous short-term missionaries over the last two decades—mostly to surrounding nations, according to Joint Christian Services International, a 24-year-old partnership of Christian organizations in Mongolia.

“They’re quick to share the good news,” Station said. “They take to heart the missionary calling to ‘conquer’ the world for Christ.”

Opening Up

Christianity moved into Mongolia the minute democracy opened the doors. Some missionaries were literally standing at the border.

“I spent a few years in northern China waiting for Mongolia to open up,” said missionary Sharon Luethy, who went in to teach English and would eventually write a curriculum on the Mongolian language. She remembers walking into Mongolia for the first time: “There was nothing in the world to prepare you for something like that.”

The country’s change in governance was remarkably calm; after 70 years of Soviet-sponsored communism, it only took three months of peaceful protests for the government to step down in early 1990.

The economic switch was harder. Ninety percent of Mongolia’s trade and investment was with the Soviet bloc, according to Columbia University history professor Morris Rossabi. “The result was tremendous unemployment, inflation, tremendous poverty.”

“It was like walking on the moon,” Luethy said. “Everything was state-run and -controlled. The TV was black and white, and only got a couple of stations. The state radio was piped into your house. It was so much like the Soviet bloc.”

Luethy began teaching English and Christianity in a country where nobody knew either. Some say there were only four Christians in the country of about 2 million when she arrived.

“Everyone was very, very nationalistic, and, except for some young people, very closed to Christianity,” she said. Religion had been banned—sometimes brutally—under communism, and when permission was granted again, most returned to their Buddhist roots.

The young people interested in Christianity were really young—those who first came to Christ were in middle school and high school, Luethy said.

“That was a massive spark,” she said. “A couple of them became believers and led their friends to Christ. Then they would tell their friends.”

With uncanny good timing, United Bible Society released a Mongolian translation of the New Testament two weeks after the country’s first free elections. The literacy rate under communism was 97 percent, and while there wasn’t a run on Bibles, Mongolians who did get one were able to read it.

That’s an unusual beginning, said Kwai Lin Stephens, executive director of Joint Christian Services International. In most areas of the world, the gospel arrived before literacy.

“It made it a lot easier to teach and learn,” she said. “The people could read the Bible for themselves. You would hear of Christians who read the whole New Testament within three months of becoming a believer.”

Right on the Bible translation’s heels, Campus Crusade for Christ (now Cru) swarmed in with the Jesus film. Evangelists would often pair the two, showing the movie and then handing out copies of the Bible.

“The effect of the dual use of the Jesus film and the New Testament . . . cannot be underestimated,” Hugh Kemp and Bayarjargal Garamtseren wrote. “They have been instrumental in hundreds of Mongolians becoming Christians.”

By 1993, the number of Christians was estimated at 2,000. Fifteen years later, estimates reached 8,000 to 10,000. Almost 10 years later, the numbers have grown to 30,000.

Education and the Prosperity Gospel

Nobody is arguing that Mongolia’s theology is perfect. Christianity is relatively young—churches are just becoming multigenerational as those middle- and high-school Christians age—and the country had no history of Christian tradition.

“A lot of times in the West, we forget how much our heritage and the modeling and resources we’ve had help to train us,” said Mark Wood, director of Mongolia’s Kingdom Leadership Training Center, which provides diplomas and degrees in Christian leadership. Many Mongolians don’t understand that ideas can be “heterodox” or “heretical,” he said. “Many don’t even have that category.”

With its biblical illiteracy and base of spiritual shamanism, Mongolia has all the characteristics of a country that should fall hard for the prosperity gospel, said Tom Terry, former president of Mongolia’s Christian television station.

And there is definitely an “undercurrent” of it, Terry said. A few prosperity gospel preachers have held events, some of Joyce Meyer’s materials are available in Mongolian, and she appears on public television.

But overall, the prosperity gospel has not flourished like one would expect.

Part of the reason was the solid theology of those first missionaries, Stephens said. “Another thing that was unique, when compared to other central Asian countries, was Mongolia’s Bible education.”

The Ulaanbaatar Bible School was started by Presbyterian Daniel Lam in 1992, offering two-week training courses every other month. Three years later, it began offering full-time training as Union Bible Theological College; today, students can earn bachelors degrees and master of divinity degrees.

The school has more than 600 graduates, and was followed into Asia Theological Association accreditation by the Mongolian School of Theological Education by Extension and Mongolia Trinity Bible College. There are a half-dozen others: the Assemblies of God have graduated 200 from Mongolia Bible School since 1994; the Lutheran Bible School began around 2010; and the Christian and Missionary Alliance’s Kingdom Leadership Training Center has graduated 34, enrolled another 40, and become accredited—all in the last seven years.

In the 600 or so churches in Mongolia today, more than 400 leaders have some level of formal Bible training, Stephens said. (Ten of the leaders have their doctorate of ministry, 48 have a masters, 138 have a bachelors degree, and 215 have certificates.) Many laypeople have earned degrees as well, she said.

“For a small church population, Mongolia has quite a high number of trained people,” she said.

They’re trained enough to have a throw-down, decades-long argument over how to correctly translate the Word for God. Some use “Burhan,” the Mongolian term for deity. But “Burhan” is also used for Buddha, so others prefer terms like “Lord of the World.”

But Southern Baptist missionary Eileen Swarr, who also uses a pseudonym, said God has used even that painful argument.

“There has been widespread ‘discussion’ since the mid ’90s on biblical terms, including the terms used for God,” she said. “This has kept many Mongolian leaders pursuing Biblical knowledge and theology. There is now a group of Mongols translating the Scriptures from the original languages.”

Media and the Prosperity Gospel

The quick move by local pastors and churches into deeper theological education probably played a big role in tamping down on the potential growth of the prosperity gospel, Wood said. “Another reason [it] did not spread so easily is that Mongolians are very practical people and saw that the prosperity gospel just didn’t work.”

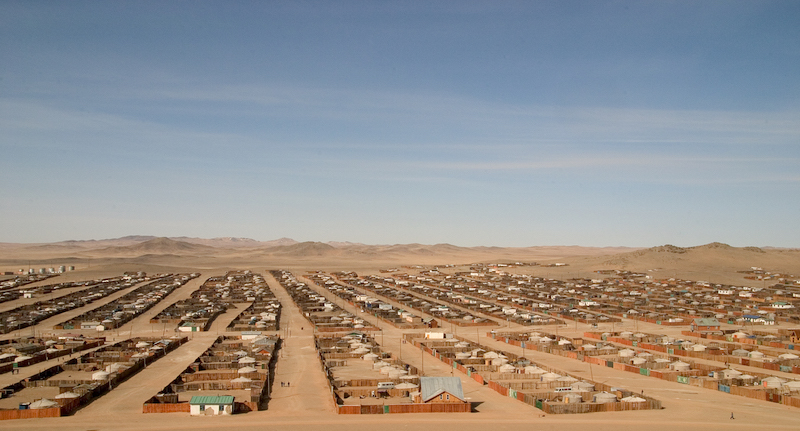

Christian television and radio also helped. Mongolia is one of the world’s most sparsely populated countries—there are only 1.9 people per square kilometer. Perhaps because of that isolation, Mongolians tend to turn the TV or radio on whenever they’re home.

Eagle TV—a partnership between Mongolian businessmen and the South Dakota evangelical nonprofit AMONG Foundation—began broadcasting Christian programming and independent news in 1994.

In the 2000s, Eagle TV aired Bible movies—think the ’80s and ’90s flicks on Abraham, Jeremiah, Peter, and Paul—and Third Millennium seminary curriculum. Now it reaches about 200,000 subscribers through satellite dishes and major cable networks, and offers more than three hours of Christian programming a day. None of it is prosperity preaching.

“We didn’t define what prosperity theology was or attack who was teaching it, but we focused on core elements of Bible study and history,” said Terry, who led the station from 2002 to 2012. It’s impossible to count “how many eyeballs” were watching, but with only four television stations on the air in 2002, “we had a big audience no matter what it was.”

The prosperity gospel has also been largely kept off radio airwaves. The Far East Broadcasting Company began broadcasting as WIND FM from Ulaanbaatar in 2001; today it has 10 stations. Indigenously produced shows include counseling against having an abortion, how to escape alcoholism, and advice on strengthening families, said FEBC USA president Ed Cannon.

FEBC Mongolia also offers panel discussions and debates with local people, and preaching from local pastors or favorites like Charles Stanley.

“FEBC concentrates on finding indigenous, top-of-the-line, theologically sound pastors,” Cannon said. “We could make a lot more money putting on prosperity preachers, but we’re not about to do that.”

Growing Oak Trees

Spreading Christianity in a country with no history of the gospel is hard, long work. It can be discouraging to see the growth of Christians slow, or to watch them stumble into cults or muddy theology..jpg)

Added to that, life in Mongolia—where the average winter temperature is -13ºF, street crime is common, and many are isolated—is hard.

But the work is crucial, partly because of the country’s continued strategic importance, Wood said. Seven hundred years ago, if those 100 monks would have made it to Kublai Khan, “the land “from Syria into Iraq could’ve been Christian.”

Today, Mongolians can travel freely in the East; they don’t need visas to cross into places like Russia, Kazakhstan, or the Philippines.

And their nomadic history means Mongolians don’t mind the travel or the boldness required to be a missionary, Luethy said. “They have reached out to neighboring countries . . . [and] possibly thousands have come to faith outside the country.”

That’s encouraging to missionaries who labor on in Mongolia, teaching Bible classes, translating Scripture and resources, and caring for the sick, the orphaned, the hungry. They’re taking the long view.

“We’re finding it takes us about 75 to 100 years in one place to really establish a national church,” Wood said. “In the West, we think we can rush maturity, can bring about a national church in seven years and then be on to the next country.”

Not so, he said.

“People ask, ‘What are you doing in Mongolia?’” he said. “We are growing oak trees. Right now they are saplings. But 150 years from now, we hope we’ll see acorns on the branches.”

Free eBook by Tim Keller: ‘The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness’

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

In Tim Keller’s short ebook, The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path To True Christian Joy, he explains how to overcome the toxic tendencies of our age一not by diluting biblical truth or denying our differences一but by rooting our identity in Christ.

TGC is offering this Keller resource for free, so you can discover the “blessed rest” that only self-forgetfulness brings.