Note: There’s a high probability that this article will not be of interest to you personally. I hope, though, that it will be of use/encouragement to someone you do know, so even if you skip it (and I don’t blame you if you do) please consider passing it along to them.

One of my vocations is to be a generalist. Yet I almost missed my calling because I didn’t realize it was something God would call me to be.

Over the years I had frequently heard friends and colleagues who felt a call to become a specialist; not once had I heard someone say he was called to be a generalist. So I decided to become a specialist, too, and pursue a PhD in history.

I lasted a semester before dropping out.

I lasted a semester before dropping out.

It was only after experiencing what appeared to be a failure that I was finally able to recognize what I should have known all along: God had always been calling me to be a generalist, a person whose interest, aptitudes, and skills are applied to a variety of different fields.

It may seem peculiar that some of us could be called by God to pursue dozens or even hundreds of subjects in order to develop what will be, at best, a superficial understanding of each. Perhaps the strangeness of the idea stems from the assumption that the path of the intellectually oriented generalist parallels that of the intellectually oriented specialist. But what if instead of being akin to the vocation of an academic, the generalist is called to be like an artist?

Knowledge-Seeking as Performing Art

The first art forms developed by humans were likely to have been performing arts, artistic expressions such as acting, mimicry, singing, or dance performed in front of a live audience.

The audience for such art forms, however, doesn’t necessarily have to be our fellow humans. The performance may be for God, as a form of worship. The psalmist wrote about dance as worship—“Let them praise his name with dancing” (Ps. 149:3)—and in 2 Samuel 6 we find King David “dancing before the LORD with all his might.” When we enter the other side of eternity we may find the greatest works of art were those performed solely for a Trinitarian audience.

What if the generalist is summoned to a similar performance? What if we generalists are beckoned to seek knowledge not as a means for some other end but simply as an act of performance before our Creator?

This is not to say that the knowledge gained cannot be used for practical purposes or in service of our neighbor. But viewing knowledge-seeking as a performative act done for God and before God frees us to treat it as a form of ongoing artistic worship. Just as David performed for God with leaping and dancing (2 Sam. 6:16) we are free to seek truth, knowledge, and understanding in a variety of areas as a way of glorifying him.

Art of Generalism

So what would generalism (the practice of studying many different things rather than specializing in one subject) as a Christian art form look like? In his book Art and the Bible, Francis Schaeffer offers four criteria for judging a work of art that I believe would be applicable here: (1) technical excellence, (2) validity, (3) intellectual content, and (4) the integration of content and vehicle.

Technical excellence — Because we are “interested in everything” we generalists are often sloppy and haphazard in our collection and incorporation of knowledge and understanding. We often flit from one subject to another, rarely taking the time to process what we’ve learned or fitting it into a broader framework.

But just as flailing our limbs does not make a dance a work of art, flailing from one topic to another does not make knowledge-seeking artistic worship. We need to develop a type of “choreography,” a system that provides a structure from which creative expression and technical excellence can emerge. (See the addendum below for an explanation of my own quirky system.)

Validity — “By validity I mean whether an artist is honest to himself and to his world-view,” Schaeffer says, “or whether he makes his art only for money or for the sake of being accepted.” If it’s to glorify God as a work of art, generalism cannot be pursued as a means of impressing others with our erudition. For the Christian generalist, the pursuit of knowledge is a performance for God, not an act of pedantry to impress our peers. The validity comes in performing not for the applause of others but for the approval of our divine patron.

Intellectual content – The work of the generalist is to study God’s revelation of himself and his creation. As Francis Bacon wrote, “There are two books laid before us to study, to prevent our falling into error; first, the volume of Scriptures, which reveal the will of God; then the volume of the Creatures, which express His power.”

All truth is God’s truth, but it is in the first book that we find God’s most perfect revelation. Whatever knowledge we find in the second book must be reconciled with what is found in Scripture. As Schaeffer reminds us, “The artist’s world-view is not to be free from the judgment of the Word of God.” (I’d say that the reading of Scripture and study of theological topics should compose at least half of the study undertaken by the Christian generalist.)

The integration of content and vehicle — “For those art works which are truly great,” Schaeffer says, “there is a correlation between the style and the content.”

What does it mean, in the context of knowledge-seeking as a performing art, for generalism to have style and content? I suspect for each individual generalist, the answer will be different. The most I can offer on this point is an explanation of how I am trying to answer the question in my own vocation.

The stage for our performative art is our own minds—which God can see even more completely than even we can (Jer. 17:10)—and the content is our thoughts. What turns generalism into an art (or at least one major “style” of art) is “sublime pattern-matching,” seeing the interconnectedness of God’s creation in a way that impresses our minds with a sense of awe and veneration of his grandeur and power.

God takes delight not in the discovery of the patterns of his revelation (which, of course, he already knows) but with the way that the process leads us to childlike worship. It is the process that leads us to continuously repeat the prayer of the 17th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler: “O, Almighty God, I am thinking Thy thoughts after Thee!” It’s the pursuit of knowledge and discovery as a way to glorify our Redeemer by becoming increasingly enchanted by his majesty.

Addendum: I would prefer to point you to an example that effectively illustrates the system and process—the “choreography”—that is needed for generalism as an “art form.” But because I can’t think of any good examples I’ll share my own process instead.

Unfortunately, my methodology is eccentric and extreme and likely not to be of much help. It’s designed to fill in the gaps that resulted from my rather poor formal education and to serve as an ongoing, autodidactic remediation. To be perfectly honest, I’m a bit embarrassed to even talk about it (which I’ve never done before with anyone). But I bring it up in the oft-chance that it will give you some idea of how to develop your own process that will make you a more God-honoring generalist.

In keeping with the “knowledge-seeking as artform” metaphor, the “work of art” I’m attempting to create for God is a collage, an artwork made from an assemblage of different forms that creates a new whole. For lack of a better title, I’ll call this work the “Framework.” Here’s how I go about putting together the Framework.

The Core: My Propædia

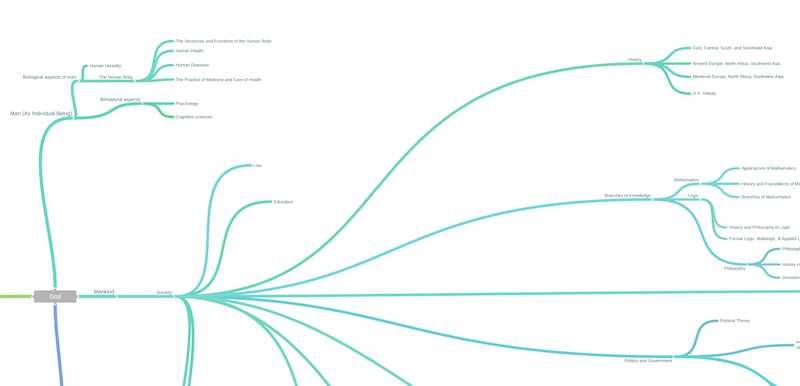

The core of the Framework is a mental version of a Propædia. The original Propædia was designed by philosopher Mortimer J. Adler as a topical organization of the contents of the Encyclopædia Britannica. My own version is a modified (and slowly expanding) model of the major topics and themes of God’s revelation, both general and special.

The image below is a segment of the “mind map” of my own Christianized Propædia. (Click here to see a full PDF version. NB: The “special revelation” section hasn’t been fleshed out yet.)

The purpose of this map is threefold: (1) To create a taxonomy of subjects that I can eventually transfer into my head to serve as the core of The Framework, (2) to provide a structure to help me see which topics I need to learn more about, and (3) to help me see a broad overview of God’s works and areas of creation to inspire awe and worship.

The Instruments: Mental Models

“What is elementary, worldly wisdom?” Charles Munger asked. “Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form.”

You may never have heard of Charles Munger (though you likely know his business partner: Warren Buffett, the most successful investor in the world), but he’s outlined some helpful insights for generalists about the need for mental models. I won’t go into detail here about what mental models I think are important, but I recommend reading Munger’s speech to get an idea of what they are and why they are necessary for developing a “latticework of theory.”

The Process (Part 1): Reading

While knowledge-seeking includes the consumption of a variety of media—podcasts, videos, graphs—the primary source, I believe, should be the reading of texts, primarily books. Every night after my wife goes to bed, I set a timer for an hour and a half and read books. I’m a fairly slow reader but in 1.5 hours I can usually read 50-60 pages of text.

I wish I had the temperament to read a single book straight through, but I don’t. Instead, I usually read 15-20 pages from 5 of 6 books a night. I don’t recommend that approach because I’m sure it’s less than effective. But sometimes you have to use whatever method works for your personality, even if it’s less than ideal.

Whether reading on ebook or print, I take notes and highlight text for the “capture” stage (see part 3).

The Process (Part 2): My Reading List

My reading plan is designed to compensate for my ignorance and weakness. Because of my lackluster education, I just don’t know as much as I should at this stage of my life (age 46). So I have to do a lot of remedial reading in topics that I should have learned about long ago.

My weakness is that I’m easily distracted by the “new” (even when the “new” is something old). I read a few chapters of a book and then discover something else that I also want to read. To keep from having piles of random, half-read books, I’ve developed an elaborate reading plan.

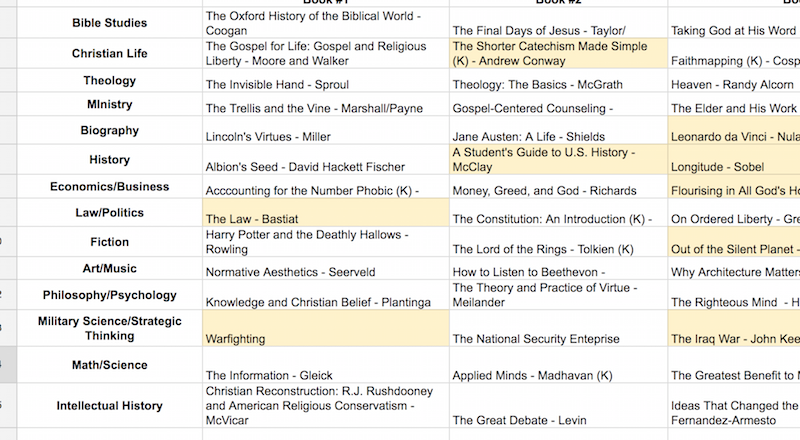

My current plan contains 57 books and is designed to last about six months (assuming I can keep the pace of 100 pages a day). I created a spreadsheet (using Google Sheets) and have three books in each of the following categories: Bible Studies, Christian Life, Theology, Biography, History, Economics, Law/Politics, Classics, Fiction, Art/Music, Philosophy/Psychology, Military Science/Strategic Thinking, Math/Science, Intellectual History, Conservative Thought, Writing / Practical Skills, and “Big Ideas.”

I have a semi-rigid rule that I can’t add a new book to a category until I’ve cleared two books from that area (either by completing them or choosing to abandon them entirely).

After I complete a book I add it under a new tab that contains all the category headings. This helps remind me to process the notes I made in these books for the “capture” stage.

The Process (Part 3): The Capture Stage

About once a week (usually on the weekend) I go through and add the notes from my recently completed books to my “capture” tool—Evernote. I use my Propædia as a general outline and tag my notes under whichever topic is most fitting.

The Process (Part 4): The Review

It doesn’t do me much good to create mental models, read for several hours a week, and take extensive notes if I don’t actually get the knowledge to stick inside my head. And if I didn’t have a deliberate process for retention my brain would be empty. (I can read a book and, within days, literally forget that I’ve even read the book—much less remember anything I read.)

To aid in retention I try to spend 20 to 30 minutes a day reading the notes I’ve put into Evernote. By doing it every day, I eventually read the same material several times a year. The daily review of information through spaced repetition makes it much easier to retain some of what I’ve read and learned.

Because I have the Evernote app on my smartphone, I’m usually able to do this in the “downtime” of my day, such as when I’m waiting in line.

The Composition: The Pattern-Matching

Each of these previous steps is merely the process of collecting the materials. Because all steps are dedicated to God, they are all essential parts of the process and performance of worship.

Still, the creation of the composition, The Framework, requires an additional step. That occurs when I put the pieces into the mental framework and think about them in a way that leads to the “sublime pattern-matching,” e.g., seeing the interconnectedness of God’s creation in a way that impresses my mind with a sense of awe and veneration of his grandeur and power.

This step distinguishes the dedicated generalist from the typical specialist. And, at least for me, it’s also the step that is the most difficult and elusive.

I can spend months putting the materials of the collage in place and never have that “aha moment” of seeing how it fits together. But when those moments do come it is like this image in the illustrated guide to PhD where the boundary gives way. No one will see it or even know about that moment but God and me—but it makes it all worthwhile.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.