Last year in Chicago, hundreds of young black men took out their guns and shot each other.

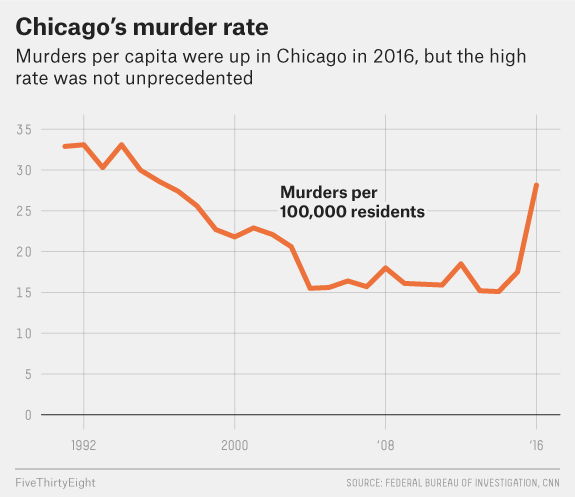

The city saw 762 murders, more than New York City (334) and Los Angeles (294) combined, and far higher than its 2015 tally of 485. Much of the violence was driven by gang activity on the South and West sides of the city; three-quarters of the perpetrators—and victims—were young black men.

Some speculate the rising violence was caused in part by a police force weakened after a video of a white police officer shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times. In August, arrests were down by a third and stops were down by 80 percent from 2015, 60 Minutes reported.

Some speculate the rising violence was caused in part by a police force weakened after a video of a white police officer shooting 17-year-old Laquan McDonald 16 times. In August, arrests were down by a third and stops were down by 80 percent from 2015, 60 Minutes reported.

Others point to longer-range reasons, including the unintended consequences of tearing down high-rise projects around 2011, which dispersed the gangs that gathered there. Even moving imprisoned gang leaders to out-of-state correctional institutions—a decision meant to cut off their communication with the street—backfired when street leadership became “chaotic and out of control.”

But in the middle of the chaos, black pastors are making a difference. Reaching out to neighborhoods, feeding the hungry, and running programs for kids, the black church is salting the city.

One of those pastors is David Washington, who prays with people and hands out school supplies on streets he knows well. He grew up in the violent South Side neighborhood of Roseland; in fact, he used to run a gang and sell drugs there.

Now, six months into planting a church in Roseland, Washington is drawing on his past to chart a way for the future.

“David has the indigenous credibility and outside resources needed to lead,” said David Swanson, Washington’s director of church planting in the Evangelical Covenant Church (ECC) denomination. “He is doing amazingly well.”

Washington’s entire story—from his almost unbelievable conversion to the bold way he takes God to the streets—is “an extension of God’s grace,” Washington said. “It saved my life.”

Growing Up Dangerous

The fifth of six kids, Washington was “claimed” by one of the largest street gangs on Chicago’s South Side in third or fourth grade. By the time he was in sixth grade, he was throwing up gang signs for the Gangster Disciples and disrespecting other gangs. In high school came the fighting and drug dealing.

“You grow up fast,” he said. “Even today, it’s the younger ones—the 14-, 15-, 16-year-olds—who are quick to kill someone to make a reputation. The older ones fall back and let the younger one take the rap.”

At home, Washington’s family was “more church attenders than practicing believers.” The more involved he got with the Disciples, the less he went to church. And the less he went to church, the more his mother and father attended, “seeking God to save me.”

But by the time he was 19, Washington was spending more than $100 a day on a severe drug addiction. A leader, or first chief, of the Gangster Disciples, Washington was targeted for death by more than one rival gang. Even worse, he was on trial for both armed robbery and also an unlawful use of a weapon, facing a possible 15-year sentence.

Saved

The day before Washington was due in court to plead guilty and be sentenced, his gang threw him a party.

“It was a going-away party,” he said. “But when you do that kind of time, you’re not sure you’re ever coming home because of what you may have to survive in the system. So it was pretty much a farewell party.”

Heavy with thoughts of his own mortality, Washington looked around the room.

“I was looking at these people, who I thought were my brothers—people I’d be willing to go to jail for, to give my life for—and God revealed to me that this party wasn’t really about me, and none of them really cared about me,” he said. “I could see guys trying to get with my girlfriend.”

So Washington left. He went home.

“I had this experience of looking at myself in the mirror and saying, ‘You threw your whole life away for nothing.’”

Agnostic at the time, Washington struck a deal with God. “If you’re up there, if you hear me, I tried everything I can think of. It’s time to try you. You’re the only one that can get me out of this situation. If you exist, if you can get me out of this situation, I will read my Bible. I will do what it says to the best of my ability. I will not claim my gang.”

Agnostic at the time, Washington struck a deal with God. “If you’re up there, if you hear me, I tried everything I can think of. It’s time to try you. You’re the only one that can get me out of this situation. If you exist, if you can get me out of this situation, I will read my Bible. I will do what it says to the best of my ability. I will not claim my gang.”

But, Washington told God, “if you can’t get me out of there in 12 months, you don’t exist.”

The next day, Washington’s parole officer didn’t show up to court. Neither did the arresting officer. Nor did the victim—a rival gang member.

The judge dropped Washington’s charge for unlawful use of a weapon and lowered the second to simple robbery. Then he sentenced him to one year of intensive house arrest probation, followed by two years of probation and around 200 hours of community service.

“I was convinced God was real after that,” Washington said. “And once convinced, there was no turning back. I gave God everything I had.”

Scared and humbled, Washington went home. And one of the phone calls he got was from a pastor at Salem Baptist Church, asking him if he’d like to go to a men’s retreat.

“It changed my life,” he said. He became close with pastor Harvey Carey, and ended up serving his community service at Salem.

“They hired me afterwards,” he said. “I never went back to doing drugs.”

But he did go back to the gangs. Or, at least, he tried.

Back to the Gangs

Washington wasn’t afraid of what his gang would do to him if he didn’t return to them. In fact, they ended up running from him, he said with a laugh.

“I began to go to the same people I used to lead and tell them, ‘I gave my life to Christ. This is real. I’m pleading with you to come out of this,’” he said. “I became real preachy, to the point where when they saw me coming down the street, by the time I got to the corner, everybody would be gone.”

Not everyone ran. Some of his friends left the gang, and together formed a rap group that would preach and minister with the Salem youth group in hard communities across the country.

“We’d hear about a party, and we’d go,” Washington said. They prayed around a strip club, in parties with machine guns present, on the streets of neighborhoods in cities like Atlanta, Dallas, and New York.

It was the 1990s, when crime rates were even worse than now. But thousands came to Christ, Washington said. “When we went to Atlanta, in one week I by myself—through just walking and talking with people in groups—I led 250 to the Lord. If our goal was to win 1,000 people to the Lord, we always exceeded it.”

Carey gave Washington more and more responsibility. “I literally trusted him with our entire youth [group]. Every time I gave him the opportunity to lead in any way, he’d hit the ball out of the park.”

“He’s very radical,” said David Sutton, a fellow pastor in the nearby Englewood neighborhood. “His fearlessness carried over into his [Christian life].”

From Gang Leader to Church Leader

Washington spent the next 15 years at Salem, doing everything from prison ministry to outreach to youth ministry. He went to Moody Bible Institute, and when he finished there, he got his master of divinity from North Park Theological Seminary.

“Seeing him—a very streetwise guy—become a scholar was the most unbelievable thing,” Carey said.

Washington spent 9 years at Oakdale Covenant Church, the largest African-American congregation in the Evangelical Covenant Churches of America.

“He truly has a holy boldness,” said Sutton, who worked with Washington on staff there. “[His youth group] did radical things like having an evangelism outreach at night, and many people came to Christ. . . . We had a Bible study, and under his leadership it doubled, maybe tripled.”

Then God led Washington to head home to Roseland to plant a church. In August, Kingdom Covenant Church began formally meeting.

The Roseland neighborhood is poor—per capita income is less than $18,000, and nearly 20 percent of households live below the poverty level. More than 17 percent didn’t graduate from high school; the same percent are unemployed.

Roseland also didn’t escape the violence, reporting 85 violent crimes in December alone. In early October, 21-year-old Adrianna Mayes was killed in front of her 1-year-old daughter. Two weeks later a 23-year-old man ran to the train station after being shot. In December, a 53-year-old man was shot and killed while shoveling snow.

“And then there are school children coming to school in [cold weather] with no coats, hats, or gloves,” Washington said. “The emotional side of this has been really difficult for me sometimes. You feel like, ‘Can we really make a difference here?’ I wrestle with that sometimes.”

Washington has certainly been making a difference. Six months in, his church plant is drawing around 70 people a week—“more than what I’d expected at this time,” he said.

Backwards

Washington is a planner, and after lots of study, he planted his church backwards, focusing first on the programs and then on setting up the Sunday worship. Though it wasn’t traditional, it has worked well, Swanson said. “To be credible in a neighborhood like his, you have to be visible, and that means you have to be on the corners praying with people.”

Kingdom Covenant works with those in prison and those getting out, helping them to provide for themselves and their families. The congregation passed out school supplies in the fall; they handed out candy, tracts, and prayers on Halloween.

“Some of the little things you’re doing are reaching out to people and causing them to be connected to the church,” Washington said. “The preaching is on a level where everyone can get it, but we’re also helping people to be missional, to understand that we’re the answer to many of the problems we see. We can’t just say, ‘I wish someone would do something.’ We’re not a large church. We don’t have a lot of resources. But we can do what we can with what we have.”

Washington is, in a sense, bilingual. “He speaks street and he speaks church,” Carey said. “He’s starting his church on the streets because that’s where he was won.”

That credibility and platform allow him to create salt and light in an urban ghetto.

“Imagine gang guys, who know their best friends, uncles, and little sisters have been murdered. They live in constant awareness of death, and no one cares about them,” Carey said.

“[Washington] has said, ‘I am staying in the ghetto, and letting the ghetto know it’s not bad.’ He’s not coming in like, ‘I’m coming to be somebody to redeem you.’ He’s saying, ‘I know what it’s like, but let me show you the love of Jesus.’”

That angle makes Washington a unique candidate to be used by God, Carey said. “I think he will become an apostle to the gang community without trying to be.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.