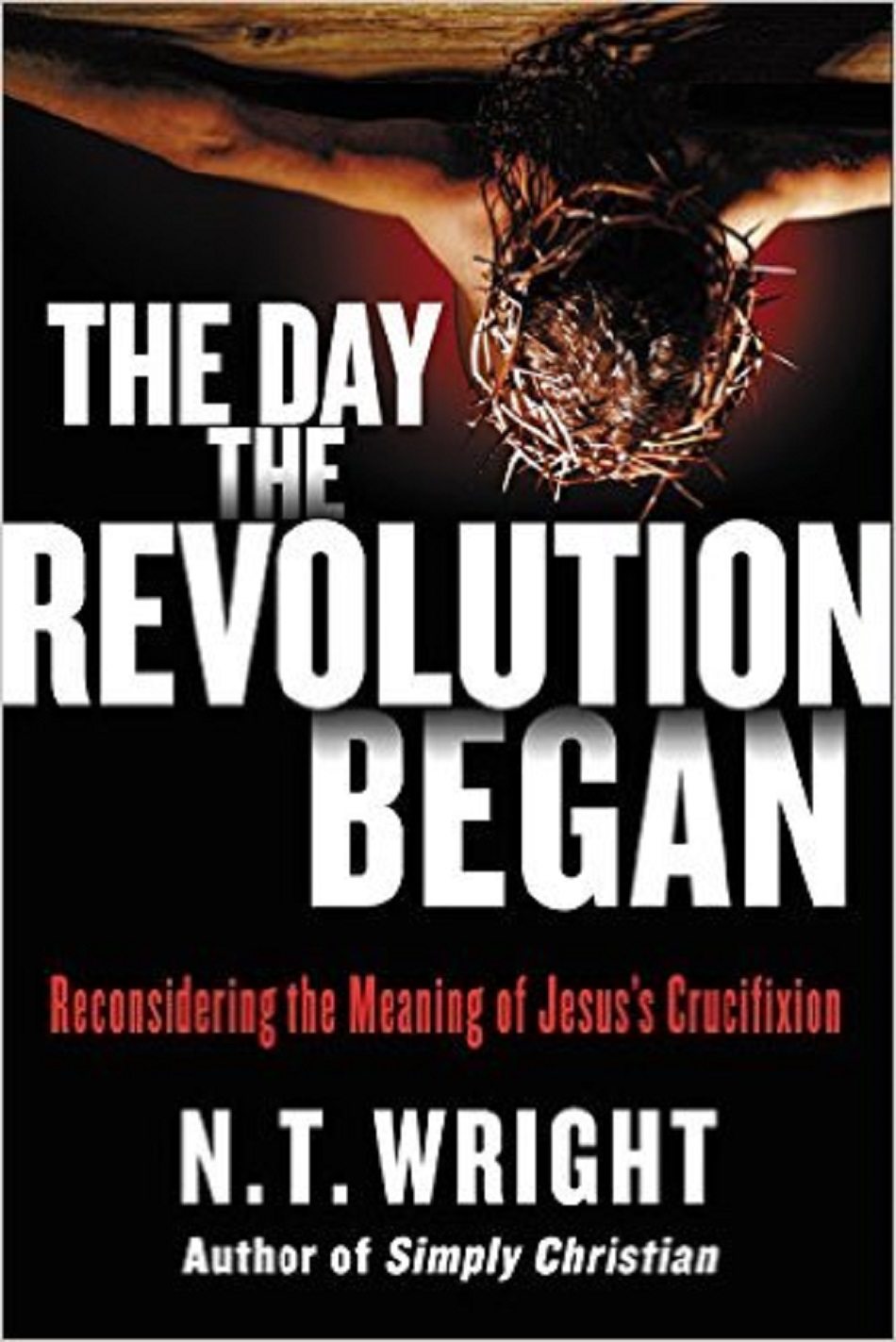

The early Christians turned things upside down with a seemingly ridiculous announcement of a revolution through the crucifixion of a Jewish teacher, such that “by 6 p.m. on that dark Friday the world was a different place.” But the church has tamed this radical message, domesticating it to the powers he came to subvert.

The burden of N. T. Wright’s latest book, The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion, is to unpack those two claims.

The traditional presentation of the gospel—e.g., the “Romans Road”—has little contact with the story the apostle is telling in that famous epistle, Wright argues. Abstracted from the story of Israel, the gospel becomes reduced to “Jesus bore God’s wrath in your place so you could go to heaven when you die.” That old-time religion had some legitimate pieces of the puzzle, but it didn’t put them together properly. Consequently, evangelicals have moralized the problem (sin merely as violations of a code), paganized the solution (an angry Father punishing his Son), and platonized the goal (going to heaven when we die). Wrigth identifies this misunderstanding of the basic plot of the Bible the “works-contract.”

Instead of this works-contract, Wright offers what he calls the covenant of vocation. The relationship God established with Adam and Eve was indeed a covenant, but it was commission to rule, subdue, and fill the earth as God’s viceroy, or royal official. So rather than the problem being reduced to “sin”—understood as a legal infraction—the tragedy goes much deeper. Sin is a symptom of idolatry. When we turn from worshiping the true God, we surrender the authority God has given us to the idols—the powers and principalities of darkness. But the covenant of vocation resumed with the calling of Abram, promising a worldwide family. Through Israel—a new Adam—God would save the world. And although the nation, like Adam, failed in this vocation, God was faithful to his covenant. Even in exile, Israel was promised God’s presence. He would return to Jerusalem and rebuild the ruins himself. Jesus is both the God who fulfills the covenant and also the true Israel in and through whom he will do it. Idolatry is the plight, victory over the evil powers through the forgiveness of sins in Christ’s cross is the solution, and thus God restores us to our vocation as prophets, priests, and kings here and now. What did the first Christians have in mind when they spoke of Jesus “dying for our sins in accordance with the Bible” (1 Cor. 15:3)?. The answer is: “A revolution had been launched.”

Anyone familiar with Wright knows he’s a master storyteller. In that regard, The Day the Revolution Began may be his best, especially for a popular audience. But more than a good narrator, Wright is steeped in the world of Jesus and Paul, bringing decades of scholarship to the task. Still more, the story he tells is vital for us to hear; he exposes the wider redemptive-historical canvas that challenges tendencies to domesticate the gospel to a platonized eschatology focused on the salvation of the individual believer from this world rather than the redemption of all believers with this world.

The story [Wright] tells is vital for us to hear.

I agree with a lot in this book. I agree with the basic gist of Wright’s critique and with much of his own proposal. That response might surprise some, including the author, with whom I’ve enjoyed spirited and edifying discussions of the manuscript. My differences lie at the point of certain details. That said, they are significant.

The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus's Crucifixion

N. T. Wright

The Day the Revolution Began: Reconsidering the Meaning of Jesus's Crucifixion

N. T. Wright

On the Gospel, the Reformers, and Idolatry

I’ve argued there are at least two major “Gentile” distortions of the gospel: (1) our kingdom-building through the gradual moral education of the human race (liberalism) and (2) God’s rescue of souls from the body and the wider creation. If our understanding and telling of the gospel could be true even if there’d never been an Abraham or people of Israel, then it’s a different gospel story than the one we find in the Bible.

Wright and I were raised in similar evangelical backgrounds. One of the most liberating paradigm-shifts for me in encountering Reformed theology was its world-embracing outlook and the way it approached the Scriptures as an unfolding drama of creation, redemption, and consummation—over against a crudely “platonized” notion of escape from “the late, great planet earth.” With the story of Israel at its heart, this biblical-theological approach contrasted with interpretations that moralized the sub-plots (e.g., “Dare to be a Daniel”). Detaching them from their overarching plot, these texts were often mined for their direct application to me, without going through Christ as the climax of God’s covenant with Abraham. I committed sins, of course—violations of God’s commands. But it wasn’t as clear to me that my sins were the fruit of a deeper problem: a sinful condition, much less idolatry. Idolatry was something other people did, in strange countries and religions, more than something to which I was prone.

We can’t deny there are popular presentations that mangle the gospel by representing the cross as the site of “divine child abuse.” I’ve even noticed in certain recent hymns something verging on a wrathful father punishing a faithful son as a “whipping boy.” The one who bore our sins is none other than God himself. But in an effort to defend the substitutionary atonement against a tsunami of criticism, evangelicals have sometimes exaggerated the penal aspect and reduced Christ’s work to vicarious substitution alone.

In an effort to defend the substitutionary atonement against a tsunami of criticism, evangelicals have sometimes exaggerated the penal aspect and reduced Christ’s work to vicarious substitution alone.

When I was growing up, salvation was definitely “going to heaven when I die.” Of course, we believed in the resurrection of the body and life everlasting, but it was a little confusing: Are we saved by death or by resurrection? It was liberating to learn that Christ was the beginning (firstfruits) of the new creation; that, united to him in his circumcision-death, everything that happened to him has happened, is happening, and will happen to me; and that my salvation is wrapped up in the redemption of a people—the Israel of God—and a place, the renewed creation where righteousness dwells. It makes a big difference in our daily living whether we think It’s all going to burn or whether we think The whole creation longs to be liberated from its bondage and share in the freedom of the children of God (Rom. 8:21).

War Against Idolatry

The Reformation itself involved a wholesale attack on idolatry. Martin Luther emphasized that idolatry was the heart of the sinful condition, even in his Small Catechism, in defining the Ten Commandments: “We should fear, love, and trust in God above all things.” In fact, the definition of the other nine commandments begins in each instance with the same clause: “That we should fear, love, and trust in God by . . .” In his Treatise on Good Works, Luther says all sins are, at root, a violation of this first commandment prohibiting idolatry. It’s difficult to understand the Reformation at all if not as a war against idolatry. In his treatise on The Necessity of Reforming the Church, John Calvin noted that idolatry was “the sin on account of which God so often punished the chosen people . . . the temple was laid in ruins . . . and his covenant people, from whom Christ was to spring, were . . . driven into exile.”

It’s difficult to understand the Reformation at all if not as a war against idolatry.

Wright acknowledges that Calvin recognized the covenant of vocation as the calling of priests to serve his purposes in Christ the high priest. Both Luther and Calvin gave wide berth to the aspect of Christ’s death as vanquishing the evil powers to which we’ve surrendered our authority and worship. A raft of terrific evangelical and Reformed scholarship has appeared in recent decades that continues the earlier trajectory—for example, Greg Beale’s work on the temple (including the motif of “a kingdom of priests”) and idolatry (We Become What We Worship). Richard Lints’s Identity and Idolatry [review] also comes to mind.

Further, it’s difficult to square the wholesale criticism of the tradition as diverting attention from our vocation as a kingdom of priests with the historical fact that the Reformation recovered the doctrine of vocation and turned believers outward to love and serve their neighbors through their callings in the world. Indeed, Luther’s distinction between passive and active righteousness (basically, justification and sanctification) has much in common with the major thrust of The Day the Revolution Began. And Wright’s concluding chapter is a masterful invitation to embrace a theology of the cross, being immersed in the gospel through preaching and sacrament, and engaging in cruciform witness and service in our worldly vocations.

Nobody likes a caricature, least of all those whose view is included in one. A caricatured critique of Wright’s account might go something like this: The story isn’t about Jesus coming back to kickstart the Sinai covenant again so that human beings can join him in his vocation to improve the world. Suffice it to say I think that Wright, in his passion for overturning distortions deeply rooted in popular piety throughout the history of the church, gives the false impression that Dante and D. L. Moody represent the best of biblical eschatology. There’s no place for exceptions in patristic sources. And Wright asserts that in their reaction against purgatory the Protestant Reformers gave the right answers to the wrong questions, as if they were obsessed with purgatory. (It’s worth mentioning that Luther himself let go of purgatory only gradually, long after his initial teaching on justification.)

As with his earlier criticisms of the Reformers’ teaching on justification, Wright frequently offers large assertions in the place of careful and informed statements of their views. Nevertheless, I agree with his judgment concerning the view he critiques.

On Israel, Justification, and Imputation

There’s nothing in my summary of his view to which I take exception. In fact, I’ve told this story (not as masterfully) and read this story in many places. I only differ on a couple of details, but those details are important. But first, agreement. Although the narrative is presented as if it were discovered for the first time, I think it’s fair to say The Day the Revolution Began puts crucial pieces of the puzzle together in a unique way. Aside from repetitive and sometimes annoying contrasts with a crassly reductionistic “works-contract,” Wright makes a solid case for the covenant of vocation.

The tragedy of the fall consists not in the violation of an arbitrary rule, but in the deeper mutiny it represents. For me, the most illuminating point of the book is Wright’s treatment of this treason as handing over God-given authority to false gods and powers. This point is made here and there in classic Reformed treatments, but (at least in my reading) not with the emphasis and centrality that Wright shows. Of course, it’s a major theme in the theology of the Christian East, but here it’s given a more biblical-theological set of coordinates.

This sets up the argument for Israel (beginning with the covenant with Abraham) as the means of God undoing idolatry and restoring the priestly vocation of his image-bearers. Although the nation also failed, like Adam, Jesus is the true Israel who fulfills the vocation, bears the curse, and by bringing forgiveness releases us from the thrall of the demonic powers. It’s not as if the curse is an arbitrary punishment added to the consequences of sin; the curse is the consequence of rejecting God for idols. When Jesus bears our curse, it’s not simply that he’s bearing punishment—in the sense of certain blows determined arbitrarily for certain crimes—but that he’s assuming upon himself the consequences of Israel’s and the world’s idolatry, which include condemnation and death.

I highlight “simply” since this is a hallmark of Wright’s treatments, including his work on justification. Sometimes I wonder if he trades one reductionism for another. In some places we read that sin (and therefore salvation) isn’t simply this or that, but in other places the impression is given that it’s not this or that at all. It’s salutary if he’s suggesting we shouldn’t reduce the cross to propitiation and propitiation to punishment for sins (335–39)—although I suspect someone who finds revolting any notion of God having any wrath, with its attendant ideas of condemnation and judgment, will still have trouble with Wright’s construction.

However, it wasn’t clear to me what he was actually affirming with regard to propitiation itself. While helpfully expanding our conception of the curse as more than penalties for violations, the argument left me wondering whether God was really in Christ reconciling the world to himself. I had trouble finding anything about God’s objective judgment not only on sin but also on sinners, which would require propitiation. I assume Wright would want to affirm that the curse isn’t an impersonal force or mere effect of idolatry, but a divine sanction imposed for covenantal treason. If so, however, I remain eager to hear what he thinks that might be.

That said, my impression is Wright has somewhat moderated his own view of justification. Deuteronomy makes clear, he observes, that in covenant justice God punishes his people, hence the exile (304). In Romans 3:21, dikaiosynē theou means “God’s covenant justice,” and sinners are “freely declared to be in the right [dikaioumenoi], to be members of the covenant, through the redemption which is found in the Messiah, Jesus” (305). So God’s righteousness condemns as well as saves; it’s not only God’s covenant faithfulness or our covenant membership, but also a verdict God declares now over all who are in Christ through faith. Wright even emphasizes that this justification is the verdict of the final judgment rendered in the present, which seems different from arguments elsewhere distinguishing a present justification by faith and a future justification according to works.

Jesus, the last Adam and true Israel, has freed us from bondage to the powers, to which we surrendered our authority in idolatry, since he died for our sins and declared us to be in the right.

Wright repeats his frequent wariness of “imputation,” but it’s difficult to understand how he can affirm an idolater can be freed from the curse by the forgiveness of sins through Christ’s blood and declared righteous without concluding this is something like a crediting or imputation. Somehow Christ’s death is the basis for the ungodly idolaters having their sins forgiven and being declared in the right. And it’s all in God’s faithfulness to the covenant with Abraham, in spite of Israel having turned its back on the oath it swore at Sinai, which Wright seems to regard (like most covenant theologians) as in some sense a republication of the original covenant of vocation. Jesus, the last Adam and true Israel, has freed us from bondage to the powers, to which we surrendered our authority in idolatry, since he died for our sins and declared us to be in the right. This is God’s promise to Abraham and through Israel of a worldwide family. Jesus has fulfilled the worldwide vocation of Israel.

If this is an accurate summary, then it’s not only consistent with but central to traditional covenant (federal) theology. “The traditions of reading against which I am arguing,” he explains, “have done their best to exclude the idea of the covenant with Israel from Paul’s thought at this key point [Rom. 3:24–26]” (307). Despite the bogeyman of a “works-contract,” however, classic federal theology turns on that connection between Adam, Israel, and Christ.

On this point as on others, it’s difficult to know exactly how sweeping Wright’s claim is. The stated thesis is that the “works-contract” narrative has a moralistic anthropology, paganized soteriology, and platonized eschatology. That depiction hardly leaves much room for negotiating. Nevertheless, the sharp “not at all” contrast turns out in various places to be “not simply.” He says,

The usual “Romans road” reading of the letter assumes that the only point Paul is making between 1:18 and 3:20 is that “all humans are sinful.” This then leads us to the “works contract”: we are moral failures; we need to get “right with God” if we’re going to get to heaven; Jesus dies in our place; the job is done. And at one level this is better than nothing. The glass may be one-third full. But something vital has been left out, like a cocktail without the all-important shot of bourbon. You can still drink it. Some important flavors are really there. But the intended meaning, the real “kick” to Paul’s argument, is missing. . . . “Sin,” then, is not simply the breaking of God’s rules. It is the outflowing of idolatry. (307–08)

A consistent use of this more nuanced way of framing the contrast throughout would have been helpful.

At the risk of being annoying, I have to say this interpretation of the “covenant of vocation,” at least as summarized here, is identical in the main elements to classic covenant (federal) theology. In fact, it fills in the outline of Wright’s narrative with rich detail. The covenant God swore to Abraham is decisive in this story, as is the covenant Israel swore when it was constituted a nation at Mount Sinai. Everything else Wright proposes as the fulfillment of God’s covenant faithfulness in Christ, ending the exile and sending out his redeemed people in the power of the Spirit for the greater conquest, is part and parcel of traditional covenant theology in the Reformed tradition.

Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven

Finally, I have some questions about Wright’s solution to the “platonized” eschatology. Here as well, his criticisms of the whole Christian tradition are sweeping, encompassing the Reformation as well. However, these same critiques have a long history in Reformed theology. Luther pledged to put Origen “back under the ban” for his Platonic speculations, and no one emphasized more than Calvin the significance of Christ’s glorified humanity as the guarantee we will be raised bodily to share in a renewed creation. Harman Bavinck, Geerhardus Vos, Herman Ridderbos, John Murray, Meredith Kline, Richard Gaffin, and others showed me the differences between Plato and Paul. In fact, some, like G. C. Berkouwer, overreacted against “Platonism” by denying the intermediate state altogether—which Wright, happily, is careful to avoid. But what do we do with the passages that teach, explicitly or implicitly, a distinction between heaven and earth?

Ever since Augustine, teachers have wisely refused to speculate about the whereabouts of heaven. There’s no literal chair the Father sits on, with the Son at his side, they typically argued. Rather, the heavenly throne symbolizes God’s sovereign authority over his creatures. Nevertheless, David was comforted that he would see his dead son again: “I shall go to him, but he will not return to me” (2 Sam. 12:23). Where was he going to go? Jewish theologian Jon Levenson has demonstrated that the intermediate state (the soul going to heaven upon death) was a widespread belief prior to any Hellenizing influence. “God is in heaven and you are on earth” (Eccl. 5:2). Are Wright’s claims about “going-to-heaven-when-you-die” as foreign to the mind of a Second Temple Jewish person somewhat overstated? After all, the lawyer’s question to Jesus, “What must I do to inherit eternal life” (Luke 18:18) was probably not provoked by his reading of the Timaeus. Is there an argument that makes allowance for assumptions of heaven—and going there—other than Plotinus’s “ascent of the alone to the Alone”?

Jesus spoke of coming from heaven and returning there, preparing a place for us, and told the thief, “Today you will be with me in paradise.” As Wright notes in passing, Paul taught the intermediate state clearly, especially in 2 Corinthians 5. No one was more insistent than the apostle that the resurrection of the body is our ultimate redemption, but he also believed in “going to heaven when you die.” As with the other stark either/or contrasts, on this question I’d like to hear more nuance and engagement with the passages our grandparents found comfort in on their deathbed along with the hope of resurrection.

Facing squarely the biblical teaching of the believer’s soul going to heaven when they die actually provides the backdrop for the ultimate hope of resurrection in a restored creation. After all, it’s called the intermediate state.

Facing squarely the biblical teaching of the believer’s soul going to heaven when they die actually provides the backdrop for the ultimate hope of resurrection in a restored creation. After all, it’s called the intermediate state. For that reason, we’re all the more stunned by the announcement in Revelation that the boundary between heaven and earth will be erased. Since Wright seems to affirm the intermediate state, the “not simply” (going to heaven when you die) once again seems more appropriate than the more absolute “not at all” type of contrast he implies in many places.

Worth the Read

Bearing these caveats in mind, I found The Day the Revolution Began exhilarating and stimulating. The last two chapters are especially stirring in their vision of a church shaped by the cross, avoiding both triumphalism and despair.

Even if one judges that Wright recoils from premillennialism only to veer too closely to postmillennialism, his defense of an inaugurated kingdom is enough to cheer the heart of any amillennialist.

Even if its provocations strike one as reactionary at times, they should be allowed to strike home nonetheless. If they’re sometimes overcorrections, perhaps they may be allowed at least to correct our distortions, exaggerations, and reductions.

Editors’ note: Join us in Indianapolis next April to learn more about the Reformation’s relevance to various areas of life and ministry. Our 2017 National Conference—“No Other Gospel: Reformation 500 and Beyond”—will celebrate the Reformation’s 500th anniversary and feature more than 50 talks from 65 speakers. Browse the list and register soon!