If you make your business the reading of books on the church, you’ll find that some Christian voices love to talk about the universal church, while others love to talk about the local church.

People on both sides will resist that characterization: “No, no, I talk about the local/universal, too.” But I’m referring to emphases, something measured in sermon minutes, column inches, and exclamation points.

Based on his new book, The Church: A Theological and Historical Account, Gerald Bray is inclined to the first camp. Broadsides against denominational distinctives and theological “hair-splitting” abound, especially in the book’s later prescriptive pages. For Bray, the greatest threat against the church today is disunity.

I, however, am someone whom Bray would probably characterize as one or two clicks too sectarian. And, well, I guess I’d say that one man’s hair-splitting is another man’s trim.

Yet it’s a good book, so I’m not sure how to respond other than to give you two review articles for the price of one. Bray deserves an overview, but I also want to identify the larger spectrum that distinguishes people like him and me, as well as the potential for danger on each side. Doing so, I think, will help any readers know what kind of book they are picking up with The Church, as well as for being fair to Bray and upfront about my own biases.

Theology + History

So article one—the overview. Does The Church belong in the systematic theology section or the church history section of the seminary bookstore? Yes.

The Church: A Theological and Historical Account

Gerald Bray

It reads like a history book, moving era by era through 2,000 years of church history. Chapter 1 negotiates questions of Jewish and Old Testament origins. Chapter 2 considers the New Testament church. Chapters 3 to 6 travel through the persecuted, imperial, Reformation, and post-Reformation church.

Yet the book’s purpose is doctrinal and prescriptive. Fundamentally it’s a doctrine-of-the-church book—what the seminary folk call an ecclesiology. Chapters up to the Reformation each conclude with a subsection summarizing lessons for a doctrine of the church. Chapters thereafter explore how the ecclesiology of Christendom then splintered like a river moving though a delta beginning with the Reformation. The final chapter (ch. 7) offers recommendations for formulating our doctrine and church practice moving forward.

At each step of the way, Bray, an Anglican minister and seminary professor at Beeson Divinity School, uses the four classic marks of the church—one, holy, catholic, and apostolic—for developing his ecclesiology. Before the Reformation, for instance, the mark of unity was viewed in institutional terms, and the mark of apostolicity was thought to depend on a succession of bishops. At the Reformation, unity became spiritual and apostolicity doctrinal.

Before the Reformation, the mark of unity was viewed in institutional terms, and the mark of apostolicity was thought to depend on a succession of bishops. At the Reformation, unity became spiritual and apostolicity doctrinal.

All together this means that the reader will acquire a doctrine of the church less like someone reading a chemistry book—with formal definitions followed by carefully outlined sections and subsections—and more like someone enjoying an evening-long conversation on a new topic. Along the way, you will encounter useful historical facts: Who was Cyprian? What is canon law? Where do the ideas of the Mass, penance, and purgatory come from? Why are Protestants especially confessional? Yet these facts are marshaled to introduce conversations in ecclesiology: Is the church the new Israel and Israel the Old Testament church? How did the Reformers view the relationship between church and state? What is the holiness of the church?

What Was the Reformation About?

At the Reformation, Protestant theologians became self-conscious about doing a doctrine of the church, Bray says, pressed as they were by the need to define their organized life together in contradistinction to Rome and (fairly quickly) to each other. Bray even suggests that the doctrine of the church was “at the heart” of the Reformation (165), which is a claim that a more “sectarian” Protestant like myself can read in one of two ways. Does he mean that the gospel itself was not at stake in the Reformation because both sides still had it (then I disagree), or does he mean that a doctrine of the church presupposes a particular gospel so that mentioning one is mentioning the other (then I agree)? I’m not sure.

In fact, let me camp out on this point for a moment since I think it’s illustrative of something larger. The book as a whole is strangely—deliberately?—quiet concerning the status of Rome and whether or not Catholics and Protestants are united in gospel fellowship. Indeed, this is one risk of blending historical and doctrinal idioms. It’s not always clear where the historian ends and the theologian begins. Bray the historian treats Roman Catholicism as one more stream in the Christian tradition—which makes sense, historically and descriptively speaking, just as one might refer to Mormon or Jehovah’s Witness “churches” for purely empirical reasons. But what does Bray the theologian think about Rome? That’s not clear. He expresses his disagreements with the office of the papacy, and he remarks that Rome has “departed from apostolicity” in a number of its innovations like the perpetual virginity of Mary (241). But would he also say that Rome has departed from the apostolic gospel?

Our Most Urgent Test

I’ve taken time to drive down this side street because it helps to situate The Church on a larger spectrum between ecumenicalism and sectarianism and illustrates the book’s driving concern.

When Bray looks out on the landscape of everything that calls itself Christian, what concerns him most is denominational disarray. Insisting on our own denominational distinctives is partly to blame: “Where Christian unity is least in evidence is at the level of denominational structures and ministry” (226). Too many of us—and here I think Bray means Baptists like myself and conservative Lutherans—employ confessions of faith that “claim to be based on New Testament but that in fact goes beyond Scripture by insisting on particular positions (regarding baptism, for example)” (241; see also 224). But the Westminster crowd shares the blame, too. Their theologians know that “their confessional positions are too rigid and exclusive,” forcing them to defend “beliefs that they know are of secondary importance (at best).” Yet they continue to do so because of “the fear of many conservatives that once a change is introduced to a historic statement of faith like the Westminster Confession, it’s impossible to know where the alterations will stop” (241–42).

Across the board, then, “Conservative Protestant theologians . . . have all too often taken refuge in an exaggerated denominationalism that artificially revives 16th- and 17th-century debates or indulged in hair-splitting controversies” (237). Again and again through the book’s final chapters, Bray treats unity as the primary value by which various questions and trends are judged. The topic of women’s ordination has been unfortunate, for example, because it “struck another blow against church unity” (245).

The solution, for Bray, is to push toward a deeper understanding of the unity and catholicity Christians have in the gospel:

Whether Protestants, and especially evangelicals, can rise above the difficulties and find a new and deeper understanding of the catholicity of the gospel that embraces a complete theological and social vision is uncertain, but . . . it is the most urgent test that they currently face.

He believes our Christian witness in the contemporary world depends on it (237). Insofar as these types of concerns animate Bray and The Church, you can understand why, when it comes to Rome, he’s quiet.

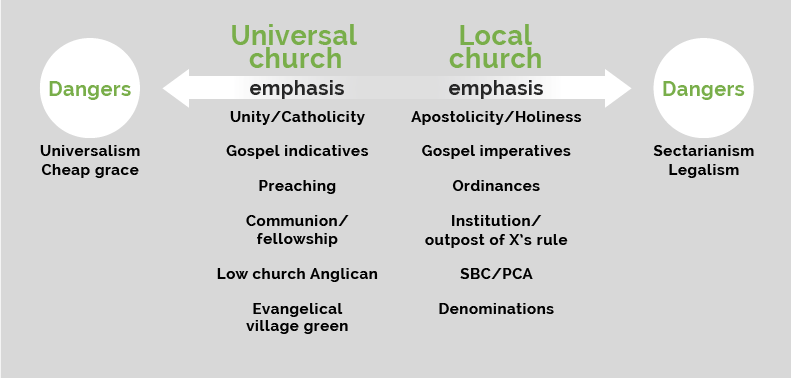

Emphasizing the Universal or Local Church: A Spectrum

Which brings us to a second article. Bray’s quiet over Rome and disdain for distinctives helps us to see a larger spectrum among evangelical voices. For our purposes here, let’s assume everyone on the spectrum is an evangelical Christian who affirms the same gospel. On one side are those who emphasize the universal church; on the other side are those who emphasize the local church.

Christians on the universal-church side tend to use their column inches and exclamation points on unity in the gospel and the catholicity of the church—those two marks. That is to say, they lean in an ecumenical direction. They’re impatient with the topics that make Christians argue, like church polity, as well as the denominations which represent those disagreements. They stress the importance of Bible preaching, teaching, and discipleship, while their lessons on local church ordinances tends to be broad, open, and non-specific. They may put in a plug for the local church and its discipline, recognizing churches are instrumental for Christian sanctification: “It will help you grow!” But it’s never the main point of the book or the Sunday school lesson and can feel like lip-service. (For instance, Bray devotes a section in his last chapter to recommending church discipline, yet he offers no positive instruction. Instead he uses the entire section to criticize how discipline has always been used, 220–21.) In their healthiest forms, the universal church-ers do a good job of putting first things first and focusing everyone’s attention on what’s essential to salvation. In their least healthy, they devolve toward soteriological universalism and cheap grace.

Christians on the local-church side spend more Sunday school lessons and blog posts on the gospel call to holiness and faithful apostolic doctrine—those two marks. They, too, talk about what’s essential to salvation—the gospel—but they’re more scrupulous (too scrupulous, the first group would say) about defining the gospel. Not only that, they acknowledge that issues dividing Christians like church polity are not essential for salvation, but they assert that these matters remain important for preserving the gospel from one generation to the next and are biblically commanded. The risk, of course, is that they can forget the more fundamental gospel unity they share when they’re arguing in comment sections over secondary matters. They emphasize the importance of the local church in the Christian life not just for instrumental reasons but for imperatival ones: Jesus commands it. They talk about preaching or formative discipline, too. But they’ll be more rigorous in their explanations of the ordinances and their practices of corrective discipline. Left unchecked, this side of the spectrum devolves toward sectarianism, parochialism, stridency, an unhealthy independence, and legalism.

The universal-ers talk about the indicatives of the gospel. The local-ers do too, but also a bit more about the imperatives of the gospel.

The universal-ers tend to define the church as a fellowship or mystical communion (to borrow a category from Avery Cardinal Dulles). So Bray writes, “The church, whatever else it may be, is still at heart the community of those who have been born of the Spirit of God” (216). Local-ers tend to define it as an outpost of Christ’s rule or as an institution (Dulles’s category again). So I’ve repeatedly called the local church an “embassy” (see Political Church [review]), and tend to define it in institutional language, like this: “A church is a group of Christians who jointly identify as followers of Jesus through regularly gathering in his name, preaching the gospel, and celebrating the ordinances” (Understanding the Congregation’s Authority, 38).

The universal-ers are more likely to think of themselves as “evangelical.” The local-ers are more likely to think of themselves as Baptist, Presbyterian, or Lutheran.

That said, different denominational traditions tend to veer one way or the other. Evangelical (low-church) Anglicans tend to emphasize the universal; Southern Baptists and members of the Presbyterian Church in America emphasize the local. To some extent, we could divide Christian publishers and conferences here, too.

The universal-ers are more likely to draw their spiritual nourishment from the so-called evangelical village green (books, blogs, conferences, music-fests). The local-ers draw from their own church or its denominational supports.

It’s tempting but probably not accurate to say that universal-ers employ parachurch ministries where local-ers don’t. Instead, the universal-ers tend to use parachurch ministries that risk replacing what the local church does (e.g., various campus ministries). The local-ers tend to use parachurch ministries that directly support the work of the local church (like denominational structures), but in the process risk depriving themselves of the resources of the larger body of Christ.

Striking a Balance?

Now, this spectrum is merely a heuristic device and doesn’t do complete justice to either side. Nearly everyone knows both sides are needed. Yet I don’t think it’s a stretch to say the emphases of some writers are further to the left or the right on this spectrum. Bray and I, who I trust share the same gospel, are probably one or two clicks apart, me rightward, he leftward. All of us, of course, think that we strike the right balance. Bray thinks he’s balanced. I think I’m balanced. Mark Dever and Christopher Wright think they’re balanced.

The fact is, all of us could do better at submitting fully to the Word of God, do better at embracing the gospel indicative and gospel imperative, do better at being the church-as-Spirit-filled-community and church-as-outpost-of-Christ’s-kingdom-rule. I do like the balance Dever strikes when he recommends keeping the fences between different denominations clear and low, and shaking hands over them often. Give me 9Marks with its local church emphases as well as The Gospel Coalition or Together for the Gospel with their universal church affirmations.

But Is the Bible Normative for Polity?

My anecdotally informed sense is that different evangelical tribes tend to come down at different places on the spectrum. Generation also seems like a factor (another hunch). I’d say evangelical Boomers and older Xers swung leftward on the spectrum from their fundamentalist parents (I have no statistics to back that up). But some younger Xers and Millennials have been pushing rightward.

To try thinking theologically, I would say at least one crucial question pushes you leftward or rightward on the spectrum: do you think the Bible provides morally binding norms for church governance or structure? That is, does it tell us whether we should be congregationalists, presbyterians, or episcopalians?

The universal-ers, often, argue that the Bible has few if any binding norms for how we structure our churches. Bray again:

- “The evidence of the New Testament is not sufficiently detailed to allow us to re-create an authentically ‘biblical’ church to the exclusion of any alternative . . . the New Testament never gives us a detailed outline of the way any particular congregation was structured” (42; also 222).

- We should therefore “pause when trying to use the New Testament as a model for our common life today” because “it is impossible, on the basis of what we know, to build a complete church structure out of the evidence of what we have” (50).

- “We can no longer re-create anything resembling the earliest Christian congregations” (239).

Most low-church evangelical Anglicans—best I can tell—acknowledge that the episcopacy is not biblical but an early church innovation that has proven useful over the centuries. So we might as well stick with it. They are, in that sense, historical pragmatists.

Local-ers, on the other hand, believe that church polity is simply a subcategory of ethics generally—call it social ethics. And unless you want to argue that none of the ethical norms of the New Testament transfers to today, then we have to do more careful hermeneutical work to determine which of the Bible’s ethical and polity norms bind us and which do not.

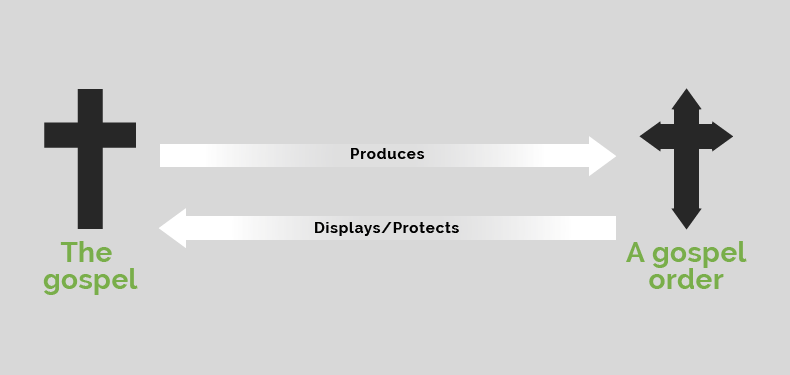

Contrary to Bray, I’ve therefore written, “Certain matters of organization are elastic and context dependent, but the fundamentals of church order are inextricably tied to the gospel faith” and are biblically prescribed (Don’t Fire Your Church Members, 15). Our gospel order (by which I mean a church’s governing structures) grows out of our gospel faith. And the Bible is sufficient for both the gospel and the gospel order that displays and protects that gospel.

Like this (from Understanding the Congregation’s Authority):

This virtuous cycle, in fact, can be placed on top of the spectrum above.

How does one’s stance on this question push you leftward or rightward? If the Bible does give moral norms for what makes a church a church and how it must be governed, then every Christian must submit to these biblical structures. If it doesn’t, our attachment to the local assembly loosens. It will be driven less by the Bible’s imperatives and more by our prudential sense of what’s good for us spiritually. If any church structure will do, then, strictly speaking, no structure will do—so long as the purposes of structure are accomplished. If you can get your church-y spiritual needs (for fellowship, instruction, worship, and elder-like coaching) met outside the local church, why not? The real drama of Christianity, it would seem, belongs to the self-governing Christian. We’re all free agents.

(In all likelihood, Bray does think some matters of church structure are biblically required, like, Do elders have any authority? Should churches discipline? Which means he risks being inconsistent when he argues against a New Testament pattern.)

This isn’t the place to jump into the conversation about whether or not the Bible determines our church order. But this difference between Bray and me is why I conclude with a “yes” to reading his book if you’re looking for a good history of ecclesiology, and “no” to reading it if you’re looking for a doctrinal and ministerial path forward for evangelicals.

Wonderfully, Bray and I both affirm that our membership in the local church isn’t finally a matter of instrumentality or imperatives. Our call to join ultimately roots in the gospel indicative. We join churches, Bray says, because it’s “an essential part of the identity of individual Christians” and our “primary community” (249). That is, we join churches not only because it’s good for us or even that we’re commanded, but because it’s what we are—members of Christ’s body and family. Praise the Lord!