It broke Larry Konneman’s heart when First Baptist Church of Ellisville near St. Louis, Missouri, split in 1993.

“It was the worst time in my church life—ever,” said Konneman, who started coming around the church when he was 16 years old, chasing a girl who went there. He caught her, and after the two went to college, they moved back to the area and the church.

“The division split families and lifelong friendships,” he said. “It was so difficult. People that I had grown up with, loved and laughed and cried with—we ended up on opposite sides of a divisive situation. It was awful.”

It was. The 800-member church split directly in half, 400 leaving with the pastor and 400 staying behind.

The new congregation started meeting in a nearby school, eventually moving five miles down the road and putting out a sign that said West County Community Church (WCCC).

And for 23 years, the two congregations stayed that way.

Ellisville stabilized around 450 people. They cultivated strong small-group Bible studies and pressed into missions, taking more than 50 overseas trips. They also grew older, hairs graying as the carpets faded and facilities became outdated.

The attendance at WCCC moved up and down, their larger number of younger families more prone to transition. They started an award-winning Christian school, began a vibrant Upward Sports ministry, launched numerous women’s neighborhood Bible studies, and built a beautiful facility.

And then one day in late 2016, Konneman’s pastor had some news.

“I’ve been approached by West County Church,” Ryan Bowman told Konneman and the other leaders. “They want to talk about the possibility of a merger.”

Konneman’s mouth fell open. “Are you kidding me?”

Bowman wasn’t. And Konneman, though he “just didn’t see any way it could be possible,” didn’t want to hurt Bowman’s feelings.

“Well, it won’t hurt to talk,” he said—the universal way of letting someone down.

So the leaders of the two congregations talked. And they prayed. And they asked their congregations what they thought.

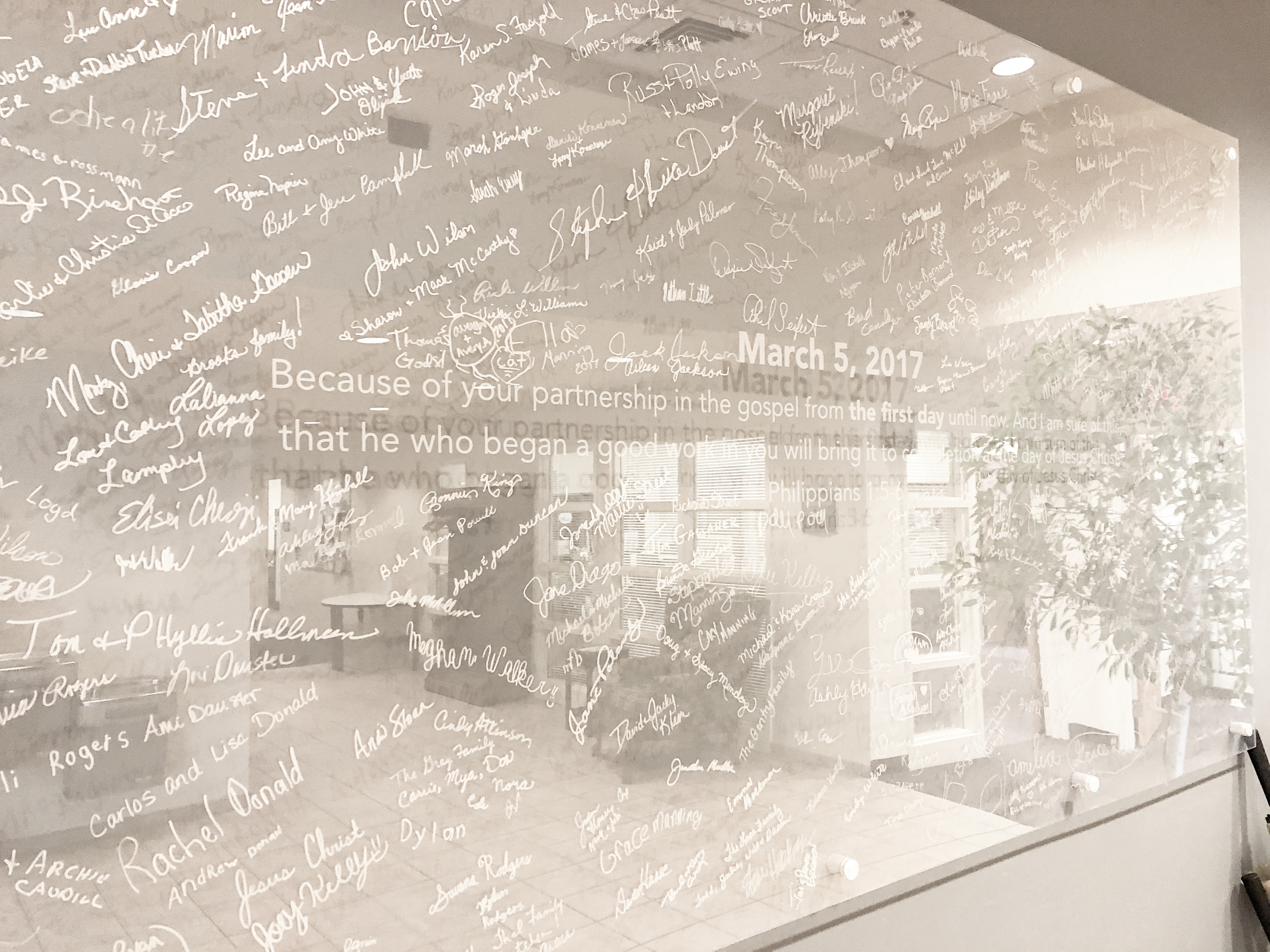

And in 2017, the two congregations held their first worship service as a brand-new, unified church.

“I’ve been in the St. Louis area all my life, and have never seen this happen,” said Jim Breeden, who was working as director of missions at the St. Louis Metro Baptist Association and helped with the merger. “I’ve never seen a church split reconnect . . . but it was clear from the first meeting that it was of God.”

First Baptist Church of Ellisville

Oddly enough, this wasn’t Bowman’s first crack at church reconciliation.

“My first congregation out of seminary had been through a split,” he said. “We actually had a reconciliation service between the two churches.”

They didn’t merge, but did both offer forgiveness for things that had happened. (Both churches had new pastors, and “I’d gone to seminary with the other pastor, so that made it easier,” Bowman said.)

He pastored for nearly 11 years in the United States before moving to Greece. There he spent five years as an International Mission Board missionary, providing humanitarian aid to the flood of refugees from North Africa and the Middle East.

“I don’t know any other pastor with a bigger heart,” said Konneman, who led the search committee that called Bowman in 2014. By then, Ellisville was 55 years old and starting to show its age. The buildings were frayed and out of date, and there were more members in their 90s than in their 20s.

“We needed to update basically everything we had,” Konneman said.

That wasn’t an easy sell; after all, few of the members would use a new nursery or preschool classroom. “I know you’re a senior, and you won’t see anything from this,” Konneman, who was 63, told them. “But we need to do it for our families,” and for those they wanted to draw in.

The congregation agreed. So Ellisville’s leaders talked to architects and builders. They raised questions and reviewed quotes. They asked for and pledged money. The first phase would cost more than $1 million; Ellisville approved it.

But just before they could get started, Bowman remembered WCCC.

West County Community Church

Just down the road, the WCCC congregation kept the same pastor but went through attendance “cycles, up and down, over the years,” said Pieter Barnard, who became an elder in 2015. In 2016, the WCCC pastor moved out-of-state, leaving around 120 members.

“The church was really struggling financially,” Barnard said. “I can’t remember how many meetings we had—sometimes the three elders met twice a week.”

“What should we do?” they asked each other. “How can we keep this church alive?”

Turns out, there’s a lot you can do to get by. WCCC elders lined up pastors to fill in on Sundays; later, they hired an interim. When staff members left, they left the positions empty. (Three or four church ladies volunteered to cover the office in shifts.)

Instead of a colorful, multi-page bulletin, WCCC printed a simple order of service in black-and-white. When one of the air conditioner units broke, it was never repaired. When contracts for servicing equipment ran out, they weren’t renewed. And the $90,000 annually given to support the Christian school was cut back to $8,800.

“We never thought about closing the church,” Barnard said. One reason was they didn’t want to shut down the Christian school, which had about 125 students. Another was the facilities. WCCC has a beautiful newer building on 29 acres, with sports fields, a pond, a full school, and a separate building for the youth group.

“I know the church is the people, not the buildings,” Barnard said. But he also recognized the blessing of having a beautiful worship space. “We wanted to use it.”

Barnard and his fellow elders thought about becoming a multisite campus of a larger church, but weren’t crazy about preaching on a screen. They thought about merging with another struggling church. (Barnard read Better Together: Making Church Mergers Work and found it “very helpful in framing what might be the right approach.”) They even identified their last resort—handing the church building over to the St. Louis Metro Baptist Association for them to replant in.

It was impossible to know what to do. So WCCC went for a walk.

Jericho Walk

It might’ve been the children’s director who suggested the idea.

“Every night we met and walked around the building, praying together,” said Stephanie Little, who was then the director of women’s ministries at WCCC. About 60 people would show up to walk slowly in pairs, praying out loud as they circled the building. Every lap had a focus—often it was repenting of pride or asking for unity.

Joy came out of the heartache. But there was also joy in the midst of it.

“It was the first time in my life I’d experienced something like that,” Barnard said. “It was amazing.”

They’d circle seven times, then end by all praying together. But unlike the Israelites at Jericho, they didn’t stop after seven days. They kept going for weeks, then months.

“It was a great time to keep everyone focused on the Lord, because there were so many unknowns and so many scary things,” Little said. For children and others itchy for something to do, the physical movement was helpful.

“Joy came out of the heartache,” she said of the merger. “But there was also joy in the midst of it.”

Obvious Potential

It’s a little hard to tell who approached whom. The first moves were tentative, and there were some third-party, can-you-tell-him-if-he-asked-me-out-I’d-say-yes phone calls.

But it’s not hard to find the connection point.

When Bowman moved to Missouri, he and his wife started looking for their boys’ first American school experience. They both liked WCCC’s Christian school.

“We were quickly told, ‘Hey, don’t you know what church runs that school?’” Bowman said. “But we put our boys there anyway. We felt it would be a good environment for them, and we thought it would be okay.”

And it was okay. It had been 21 years since the split—many people had moved away; of those still there, the pain was more muted and emotions more settled.

The Bowman family started to get to know the WCCC people involved at the school. Bowman’s wife became a substitute teacher. His kids settled into their classes. And while chaperoning a school field trip, Bowman had a great time chatting with soon-to-be WCCC elder Barnard.

“I started wondering what it would look like to see the two churches reconciled,” Bowman said. He wasn’t thinking about a merger—he’d never heard of a split church getting back together—but a reconciliation like his old church did.

And then he was thinking about a merger. Because WCCC had young people, a newer building, small staff, and dwindling finances. And Ellisville had an older congregation, buildings that needed $6 million in renovations, a full staff, and a healthy budget.

“To a pragmatist, what’s not to like?” Konneman said.

To Bowman the reconciler, the potential was obvious.

‘Broken Pieces Put Back Together’

Bowman mentioned something to a school board member, who mentioned something to Barnard. He spoke to his fellow elders, who officially approached Ellisville. When Konneman heard the idea, he was “completely shocked.”

In many ways, the journey would be harder for Ellisville. An older, more stable congregation, they had more people who remembered the split. They hadn’t been looking to merge with anyone—in fact, they were on pace to spend millions remodeling their space. And they’d be the ones to leave their building—the place where they were baptized, where they’d gotten married, where they’d watched children grow, where they’d buried friends. It would be their kitchen equipment and stained glass windows auctioned off, their building sold and torn down.

“I just didn’t see it,” Konneman said. “I didn’t understand it. I wasn’t in favor of it.”

Neither was Jim Breeden from the local SBC association, who had been helping WCCC think of options. He’d been an area pastor when the original church split, so he knew the history. He could see incompatibilities in the more traditional Ellisville and more contemporary WCCC. And he’s not crazy about church mergers in general, because “I always like more churches rather than fewer churches.”

But Bowman had seen the vision. “What started primarily around a stewardship dialogue—what’s the best use of these resources?—quickly changed into a gospel-centered dialogue of not only reaching the community but also exemplifying restoration,” he said. “The gospel is seeing broken pieces put back together. That’s the redemptive story.”

Breeden remembers one of the church leaders telling him they believed God might be restoring what had been broken. “It was like the Spirit of God just prodded my heart,” he said. “I thought, Oh, my, I don’t want to be opposing that.”

He mediated the first meeting between their leadership boards, where it helped that none of the WCCC leaders had been around for the split.

“They were all people I liked immediately,” Konneman said. “I could tell they were sincere and loved the Lord.”

By the end of the meeting, he was in tears. “I never dreamed God would bring us around the table like this,” he told the room.

“In my spirit, I thought, It’s a done deal,” Breeden remembers. “This is going to happen.”

Maybe. But nobody had run it past the people yet.

‘Are You Kidding Me?’

“Are you kidding me?” a surprised Little said when her husband, a WCCC elder, told her they were talking about merging with Ellisville. (A few miles away, Konneman’s wife was saying the exact same thing to him.)

But it didn’t take long to see that “this is what we’d been praying for,” Little told TGC. “When you walk through such heartache, you’re looking for God’s heart. And his heart is always reconciliation and unity—our whole theme as we prayed around the building was unity because we had been so fragmented.”

This would be unity pressed down, shaken together, and running over. “It was the biggest answer to unity we could ever see,” she said.

At Ellisville, “some people were very excited about the prospect—they were looking at the shiny new buildings,” Konneman said. “But there was also a lot of hesitation.”

It wasn’t so much the re-joining that was hurting their hearts. It was leaving their home church and the location God had originally called them to. And it was working past old anger and faded pain to get to the hard goodness of reconciliation.

“The feeble chicken part of me wanted to tell people about the new campus and how nice it was out there, instead of looking at it from the way God was looking at it,” Konneman said. “It took a while for that to settle in on me—that we were healing a broken fellowship.”

In December 2016, more than 80 percent of Ellisville’s congregation voted to merge; half an hour later, WCCC’s vote to join them topped 90 percent.

“But it’s one thing to vote on a piece of paper,” Konneman said. “It’s another thing to live it.”

Healing a Broken Fellowship

The first service the newly restored (and not yet named) Fellowship of Wildwood held in the WCCC campus felt both good (a full sanctuary in a beautiful space) and bad (nobody felt at home).

“For me, it was the best feeling,” Barnard said. “Worshiping together with so many more voices, seeing so many people—for me, it was amazing.”

Others felt out of place, either in an entirely new place or with an overwhelming number of unfamiliar faces. “Some would tell me that it didn’t feel like home yet,” Bowman said. “While others would tell me that it didn’t feel like home anymore.”

Eventually, about 15 to 20 percent of the people would leave. Others complained. “Ryan’s door was always open,” Konneman said. “He discussed the same tired subjects over and over and over again. I’d say, ‘Ryan, how many hours have you worked this month?’ He has such the heart of a shepherd. He will not close his door.”

There were missteps. “Bringing our Awana ministries together was so hard,” Bowman said. “Theirs was on a Wednesday night; ours was on a Sunday night. I felt like it would be a nice olive branch to say, ‘Even though we’re the larger ministry, let’s move it to their night.’ But it did not work.”

The entire first year, the two congregations bumped into each other—over the preschool, over the music teams, over the small groups.

“People would come and share the difficulty, and we’d say, ‘We’re going to keep trying to keep on,’” Little said. “One of the hardest parts was having to wait through the building of shared history.”

“It took more than a year for a lot of the emotions to process,” Bowman said. “But having that first full year done—we could look back to last year’s VBS or women’s banquet or advent and say, ‘How did we do it last year?’ And instead of looking at Ellisville or WCCC, we were looking at our own new history as Fellowship of Wildwood.”

He knew things were at a turning point about 12 to 18 months in, when “I was forgetting who was part of which original church.”

Konneman, who had been teaching unity in his adult Sunday school class, said the same thing. “It feels like home now. I’m completely at ease.”

’Look What God Has Done’

The Fellowship of Wildwood sold the old Ellisville church building and property. With the proceeds, they paid off their combined debt and even put some money in the bank. They support missionaries at home and abroad. (“That was something quite a few of us in WCCC really wanted to do, but there were never enough people or resources to do it,” Barnard said. “It’s amazing that’s not a problem anymore.”)

They’ve grown to around 550 in weekly attendance, with both a full nursery and full senior-adult Bible studies. They’ve started sports ministries in the school gym and soccer fields. The schoolchildren have gotten in on the widows’ ministry. And under a new youth pastor, the youth group is growing.

The whole story “is a confirmation of prayer,” Barnard said. “Sometimes you pray and wonder if God really hears you because nothing is happening. But look what God has done here.”

Part of the fruit “has been to see God working in ways that none of us had anticipated,” Bowman said. “‘Beyond what we could expect or imagine’ wasn’t on my radar. But we’re seeing God do something new and unique—something we’re able to look back on and say, ‘None of us could have humanly orchestrated this.’”

“It’s a miracle of the Lord’s,” Little said. “That’s the way we see it, even now.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.