Historical biopics or docudramas that chronicle a period of American history where blacks are unjustly oppressed are difficult to imbibe. American period pieces involving the history of Africans and their subjugation by Anglos seem to always promise to conclude hopefully. They remind us of the sins of our fathers and remind us the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. In each film the protagonist arrives at a moment of lucidity, garners courage from the depths of their beautiful soul, and rises triumphantly from the unjust oppression, culminating in the final act of “sticking it to the man.”

This often solicits rancorous cheers from moviegoers. Yet I’m often immediately discouraged because much of what is hopeful and triumphant in the film only proves to be a mirage once I leave the theater. Somehow I leave more discouraged and sure that our world will never truly change.

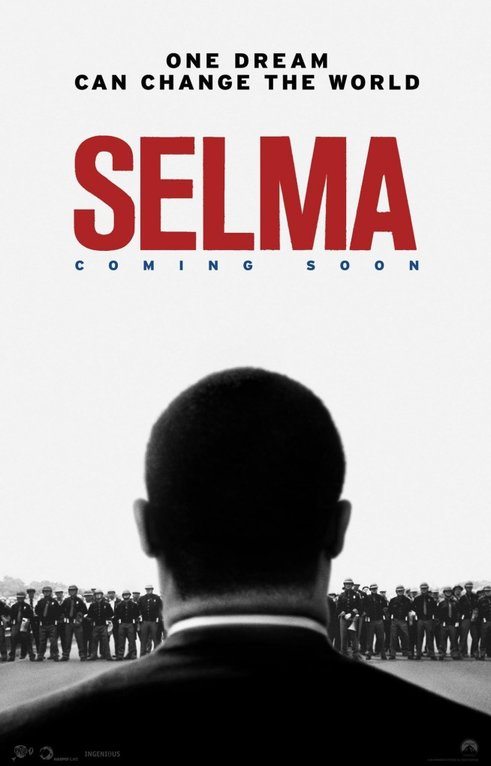

But Selma is different. I left this movie hopeful.

Raw and Honest

Selma does not cower away from the physical and emotional brutality of the struggle for African American voting rights in Selma, Alabama, during a three-month period in 1965. By concentrating on this historical vignette, Selma shines. Rather than approaching this biopic as a quest to compile the highlights of a venerated figure’s life, Selma director Ava DuVernay focuses on a tiny window of history that changed history. SCLC uniforms (black suits, white shirts, and thin black ties) and scarred stoic faces juxtaposed against the pressed and unkempt uniforms of police officers and state troopers as they clash throughout the film in raw and ugly dispute.

Further, Selma does not cower from exposing the moral failings of Dr. Martin Luther King. While the impact of Dr. King’s leadership of the Civil Rights movement is magnanimous and will rightly reverberate into history, he suffered from the common condition of profound creaturliness. This fellowship with mere mortals is a surprising strength of the film. Dr. King appears, well, human.

Selma

Ava DuVernay

Throughout Selma he’s tired from long nights, distracted by threats to his family, fearful for the lives of the faithful, and doubtful concerning the ultimate end of the movement—a side of “Doc” we seldom see in grainy microfiche. The film tastefully addresses his smoking habit, his insatiable appetite for food, and his covert sexual promiscuity. Raw and honest, DuVernay portrays a terrestrial Dr. King who is pedestrian at worst and valiant at best—all the while honoring him as a towering historical figure worthy of remembrance.

Selma’s Soldiers

As much as this movie is about Dr. King, it’s even more about the people of the movement. Selma is Jimmy Lee Jackson and Viola Liuzzo. It is John Lewis, Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, and Diane Nash. It is Cager Lee and Jonathan Daniels. Selma is first names: Coretta, Bayard, Mahalia, J. Edgar. Selma is evil finding a face in the Bull Connor-esque county sheriff Jim Clark and Alabama governor George Wallace. It is the dubious and spurious “help” of Malcom X. Selma is the acronyms LBJ and MLK. Yes, Selma is about voting rights, civil rights, and social justice, but it is primarily about the people who aided in the denaturing of America. It is a tale of their struggle, their uncertainty, their brotherhood, and their fellowship.

Selma climaxes on the battleground of the Edmund Pettus Bridge. A King-less mass of people, led by Hosea Williams and John Lewis, solemnly marches across the rusting hulk as hauntingly beautiful gospel music fills the scene. You’re immediately hurled into slurred staccato images of terror, punctuated by Billy clubs violently impacting faces and a steady saturation of tear gas clouding your vision—while Jim Clark leads the cavalry of officers against the unarmed and helpless civil rights infantry. Crowds of people running in terror from those who lack vision of humanity in the souls they torment. Edmund Pettus’s pavement quickly runs red with the blood of these social justice martyrs. Raw and honest.

Selma feels bygone. It feels familiar. Somehow this film captures both the tenuous fight for freedom of years gone while simultaneously singing a contemporary aria that daily crescendos. One cannot but notice this film coinciding with the continued unrest in Ferguson, Cleveland, and New York. Names like Jimmy Lee, Viola, and Jonathan are replaced with those such as Tamir, Eric, Rafael, and Wenjian. The SCLC war room boasts a multi-ethnic presence. A sea of colorful faces fight for freedom. “Blackness” alone is not the primary color of the civil rights movement—nor of Selma for that matter. Oneness is the color of the movement. The film doesn’t merely pit blacks against whites as much as it places those who fight for justice in stark opposition to the systemic powers aiming to thwart its work. Selma feels bygone. It feels familiar.

Ultimately the band of protagonists arrives at moments of lucidity, garners courage from one another, rises triumphantly from the fog of death and tear gas, and “sticks it to the man.” Is this simply another historical drama that leaves the audience discouraged because of the world into which they re-emerge? Not so much.

Our History

Selma is much more than Black history. It is American history. It is our history. Within all of us we understand the fight and struggle for change in order to make a better life for those who will come after us—even if that means that we won’t live to see that change. Selma is not a movie for African Americans. It’s a movie for all Americans.

We are not the sum total of the sins of our fathers and forefathers. The film closes with a song titled “Where Do We Go From Here?” Should Dr. King have lived to see today he would smile at the fruit of his labor and yet still don his SCLC uniform and resume his labor. But when he’d look around at those whose arms are linked with his, he would find an ever-growing throng of colorful faces continuing to sing, “Precious Lord, take my hand, lead me on, let me stand.” And when I walk out of the movie theater, I see this. I see work yet to be done. I see setbacks. I see progress. I see change.

I left Selma hopeful.