Was Peter crucified upside down? Did Thomas make it to India? Were all of the disciples except John martyred? If such questions have ever crossed your mind, After Acts: Exploring the Lives and Legends of the Apostles will interest you. Even if they haven’t, it’s still worth exploring the traditions surrounding the closest witnesses to the life and ministry of Jesus.

Dozens of books have been written on the lives and legends of the apostles. Perhaps the most popular is The Search for the Twelve Apostles (Tyndale, rev. ed., 2008). One Amazon reviewer claims, “All other books on the apostles will be judged against this one.” That may be true, but I see three distinctions that set After Acts apart from the rest.

Three Distinctions

First, After Acts examines traditions on the 12 apostles but also includes Luke, Mark, Mary, and Paul. Books on the apostles often ignore Mark and Luke, but Litfin carefully considers what we need to know about them since they wrote two of the Gospels. While little evidence backs the popular claims that Mark was dragged to death by a horse in Egypt and that Luke’s bones remain in Italy today, sufficient testimony confirms their authorship of their respective accounts.

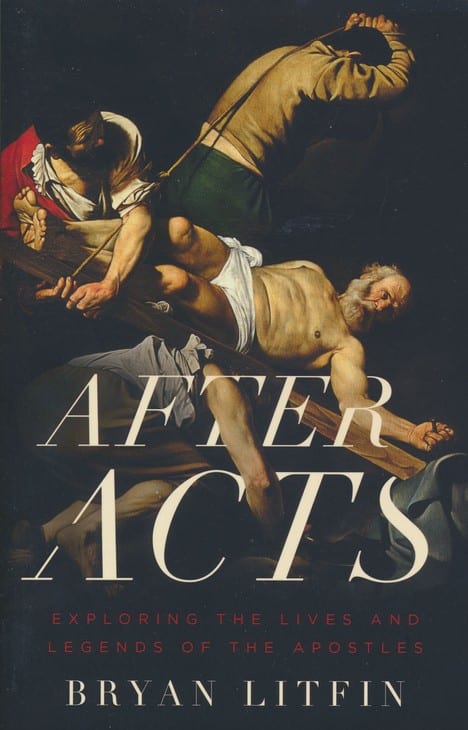

After Acts: Exploring the Lives and Legends of the Apostles

Bryan Litfin

After Acts: Exploring the Lives and Legends of the Apostles

Bryan Litfin

Second, Litfin includes helpful life lessons throughout his book. For instance, he begins the section on the “other apostles” by noting that some people never receive credit in this life for their work, but this doesn’t mean they’re unimportant. Litfin writes:

Even some of the apostles were like this—such as Andrew, who isn’t highly celebrated today, but who led his brother Peter to Christ and changed the world as a result. Just because you aren’t famous doesn’t mean you don’t count. (125)

Amen.

Third, and most importantly, After Acts is based on careful and critical history. Litfin, professor of theology at Moody Bible Institute, approaches the question of the apostles’s fates as a trained historian. Rather than blindly following later legends, he skillfully examines the evidence. He focuses primarily on evidence from the second and third centuries and only cautiously uses later sources. As a good historian, Litfin talks in terms of probabilities rather than certainties. He rightly concludes that we know a good deal about Peter, Paul, and James the brother of Jesus, but little about Thaddeus, Simon the Zealot, and James the son of Alphaeus.

A Cautious and Careful Historian

Having written my own academic book on the fate of the apostles, I was pleasantly surprised to read Litfin’s cautious assessment of the historical record. He examines each apostle carefully and leaves us with a fair and sober-minded conclusion. For instance, writers often think Simon the Zealot was a member of the revolutionary party that helped spur the Jewish uprising against Rome in AD 66. Many commentators base their entire perception of Simon on this claim! Yet as Litfin rightly notes, the term “zealot” during the time of Jesus’s ministry likely referred to someone who had intense devotion to God and his law (Acts 21:20; Gal. 1:14), not a member of the official “zealot” party that attempted to overthrow the government.

Consider another example. One popular tradition claims Bartholomew was flayed to death. Liftin points out that the flaying story first appeared in seventh-century Armenian church traditions. Does this mean the story is false? Not necessarily. Flaying can be traced back long before the time of Christ. It was practiced in Turkey, China, and many other eastern countries. At best, the claim that Bartholomew was flayed to death is possible. It may have happened, but the evidence is late. Litfin rightly concludes, “His death as a martyr by flaying is not well attested; and even the story of his martyrdom by more conventional methods has the ring of legend to it” (136).

One last example may be helpful. As Litfin notes, there is both convincing biblical and extra-biblical evidence supporting the martyrdom of Peter (e.g. John 13:36–38; 21:18–19; First Clement 5; Ascension of Isaiah 4:2–3; Against Heresies 3.1.1; Prescription Against Heresies 36, and more). But what about the claim he was crucified downwards? Did Peter consider himself unworthy of crucifixion like his Lord and request to be crucified upside down? As Litfin notes, this explanation does not show up until pseudo-Hegesippus in AD 370! Can we trust such an account?

The first record claiming Peter was crucified upside down appears in a late second-century document called the Acts of Peter, a legend-filled apocryphal text. The Acts of Peter makes no mention of Peter’s humble request to be crucified upside down. Rather, it says Peter’s upside-down state symbolized fallen humanity’s restoration through the cross. Is such a story believable? After noting the Romans were known to crucify upside down, Litfin writes:

However, the victims of Roman crucifixion were not given the chance to make requests about the method of their impalement. The intent was to shame them in a grotesque way, not accommodate their wishes. Therefore, the upside down crucifixion of Peter is historically plausible, though not for any spiritual reasons. (150)

These are just a few of the helpful corrections Litfin offers regarding traditions on the apostles. We can learn a lot about the apostles from his careful work in After Acts. You may be pleased at the evidence concerning the lives and fates of some of the apostles, but others may leave you disappointed. Nevertheless, it’s important we neither overstate nor understate the historical record.

Passing On the Torch

So what really happened to the apostles after Acts? Litfin concludes:

The answer is simple. They died and went on to their reward—but they also left behind their successors, the men and women who received the torch of the Christian faith and passed it on to the next generation. (184)

The apostles risked their lives to ensure following generations would receive the truth. They answered God’s call so the truth could be passed onto us. What will we do?