This episode of Gospelbound is sponsored by The Good Book Company, publisher of The Garden, the Curtain and The Cross by Carl Laferton. This storybook takes children aged 3 to 6 on a journey from the Garden of Eden to God’s perfect new creation, teaching why Jesus died and rose again and why that’s the best news ever. More information at thegoodbook.com.

“We’re not going back to normal.”

So wrote Andy Crouch and two of his Praxis colleagues on March 20, 2020, just one week after the national COVID-19 shutdown began in the United States. No essay was more widely circulated among my networks as we all grappled with the effects of this unprecedented pandemic. Crouch and his team warned us this would not be a blizzard that rages for a few weeks or a winter that lasts a few months, but an “ice age” of 12 to 18 months that would change our way of life for good.

They were right.

A week earlier than his Praxis article, on March 12, Crouch wrote “Love in the Time of Coronavirus,” a guide for Christian leaders. Much of his practical advice, seemingly drastic in the moment, has become commonplace. I’m still captivated by his hopeful vision for turning to Christ: “We need to pray for genuine spiritual authority, rooted in the love that casts out fear, to guard and govern our lives as we lead, and trust that God will make up what is lacking in our own frail hearts, minds, and bodies.” He also offered consolation: “When we realize that Jesus is present today and will be present tomorrow, we can be set free from worry.”

Nearly one year later after the initial shutdown, more than 500,000 have died. Some predicted even higher numbers, though a year ago probably most of us would’ve been shocked by the toll. Yet with effective vaccines increasingly available, we can perhaps begin to glimpse the end. But when we reach the end, what will we find? Who will we be?

Andy joined me on Gospelbound to lament the last year, assess our levels of social trust inside and outside the church, and look forward to God’s purposes in the next year and beyond.

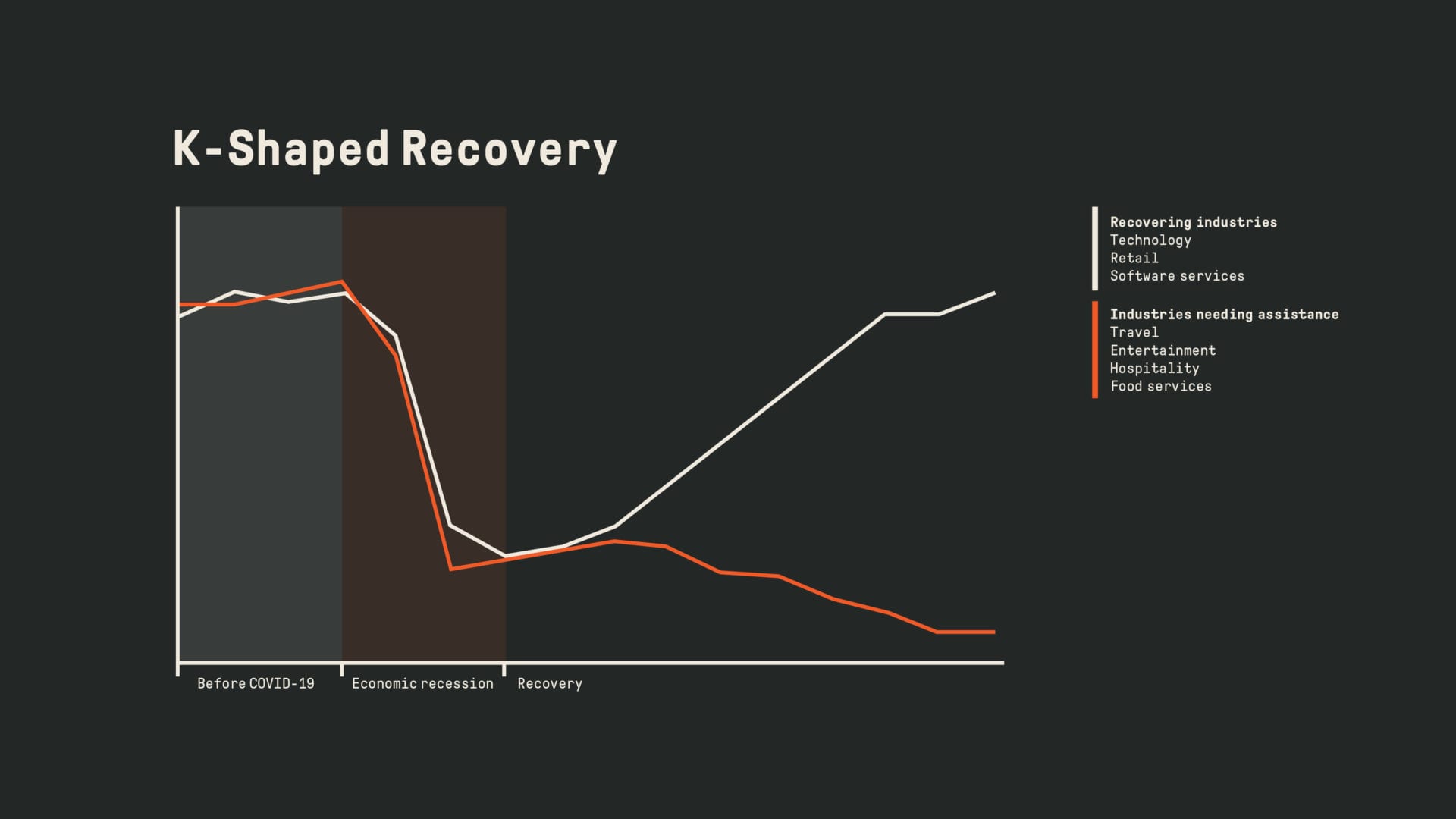

“K-Shaped Recovery” referenced in this episode:

Transcript

The following is an uncorrected transcript generated by a transcription service. Before quoting in print, please check the corresponding audio for accuracy.

Collin Hansen: “We’re not going back to normal,” so wrote Andy Crouch and two of his practice colleagues on March 20th 2020, just one week after the national COVID-19 shutdown began in the United States. No essay was more widely circulated among my networks, as we all grappled with the effects of this unprecedented pandemic. Crouch and his colleagues warned us that this would not be a blizzard that rages for a few weeks, or a winter that lasted a few months, but an ice age of 12 to 18 months, that would change our way of life for good. And, they were right. A week earlier than his practice article on March 12th, Crouch wrote, “Love in the time of coronavirus, a guide for Christian leaders.” Much of his practical advice seemingly drastic in the moment has become commonplace. I’m still captivated by his hopeful vision for turning to Christ. Andy wrote this, quote, “We need to pray for genuine spiritual authority, rooted in the love that casts out fear to guard and govern our lives, as we lead and trust that God will make up what is lacking in our own frail hearts, minds and bodies,” end quote.

He offered constellation when he wrote this, quote, “When we realized that Jesus is present today and will be present tomorrow, we can be set free from worry,” end quote. Nearly one year after the initial shutdown, more than 500, 000 have died in the United States. Some predicted even higher numbers, though a year ago, probably most of us would have been shocked by this toll. Yet with effective vaccines increasingly available, we can perhaps begin to glimpse the end. But, when we reached the end, what will we find? Who will we be? Andy joins me on Gospelbound to lament the last year, assess our levels of social trust inside and outside the church, and look forward to God’s purposes in the next year and beyond. Andy, thank you for joining me.

Andy Crouch: Thank you, Collin.

Collin Hansen: Andy, what did you see that so many others missed? I mean, you and your team wrote this on March 20th, quote, “To the extent that we are able to rescue our healthcare system from total breakdown immediately, that will come at the cost of creating the cultural and economic conditions of winter, likely through the end of 2021, until the population gradually and naturally acquires immunity at the cost of widespread illness and deaths or a vaccine is developed,” end quote. I mean, would you change anything from your original ice age article?

Andy Crouch: No. As it turns out, nothing in that article was novel, in the sense that plenty of people who were carefully at what was happening and had actual expertise, which I had done, like all of us, we became epidemiologists overnight. But, there were plenty of people who were forecasting that scenario. I think maybe the difference was that for many, many different reasons, people in positions of public leadership were not saying it. So, you had to go to the dark corners of Reddit to various lists that I compiled on Twitter, to people who seemed a little out there, but they were doing very careful work and had real expertise to bring to it. So, all we did was say for our community, we wrote this above all for the Praxis community of entrepreneurs, because we realized everything about all of the… We’ve worked with 190 ventures now and we care about these people.

We care about their companies and their organizations. And, we knew they had to change much faster than anyone was telling them to change. And, we also had the wider church and the wider, just our neighbors in mind. So, I wouldn’t change anything, alas. I mean, alas that it didn’t go differently, but honestly, the way these kinds of highly infectious diseases that are novel to the human species, where we have no immunity anywhere and anyone. I mean, it’s not that hard to predict how it plays out, though of course, we couldn’t predict, but we could see what was likely coming.

Collin Hansen: Andy, I re- read your essay, obviously in preparation for this interview. And, I remember at the time thinking this is important and I need to take this seriously. But, I remember thinking the projections were ludicrous. I was like, “There’s no way this is going to last that long,” which was interesting because in my context, I was one of the first people among my network to see that this was going to be a major problem. I was telling friends that this was going to last six weeks when everybody was like, “No, like three days,” or something. So, I thought I was kind of extreme. And then, I remember thinking with your piece, that just makes no sense.

I went back Andy, and I re-read it again. And, if you had asked me ahead of time, I would have thought you were projecting something of like three to 10 years, instead it was 12 to 18 months. And, that’s what I thought was just crazy. I’m like, “There’s no [inaudible 00:05:24], this is 12 to 18…” But in my mind, I’ve already begun to reshape those expectations. [crosstalk 00:05:31] But I mean, it was that kind of information overload, was very hard to know where to sift through. And, I also was completely taken aback by the economic situation. So I thought, in my mind, I’m thinking 2008, 2009, because that’s what my experience was.

Andy Crouch: Right.

Collin Hansen: You even saw this though, you saw the likelihood that the economic recovery would look V-shaped with some recovering quickly, and even gaining ground and others falling even further behind. Andy, what have you seen as the social consequences of this kind of variegated experience of the pandemic?

Andy Crouch: Yeah, I will say, this part, I don’t think I did see this fully coming. There are these various letters people use for economic recoveries, V-shaped, U-shaped, L-shaped. The 2008, 2009 financial banking crisis recession, those tend to be L-shaped as you have this big, deep, steep fall off, and then it takes a long time to come back. The classic epidemic is a V, that is to say very sharp drop, very quick recovery. And, that happens also in natural disasters and other things like that. But, we didn’t have the letter back then and that someone coined a couple months ago, I read it in the Wall Street Journal, which is actually K-shaped. This has been the biggest surprise to me. If you had told me a year ago that my own personal portfolio of public equities, and publicly traded bonds and securities would be worth 20 to 30% more than it was a year ago, that the financial markets would experience this incredible boom after a sharp drop for a month or two, I would not have believed you.

If you had told me that a whole sector of, just sticking to America which is the context I know of Americans, those who basically who work with screens would be better off, because their expenses would have been reduced, their income would have stayed constant and their lives materially, leaving aside the real psychological issues for everyone, would be far better off, I really did not see that coming at all. But what’s happened is, with the upper half of the K is a lovely little V for those of us who work with screens. But, those who work with things and with people, and everyone who’s labeled essential works with one of those two almost, it’s been devastating. And, this will be for millions of our fellow citizens, the defining irreversible calamity of their and their family’s lives from which they will never bounce back in their lives. Even while many of us, I am in this group, like my little bank account has done just fine.

And that divergence, that was one thing I didn’t see coming Collin, because I really, well, I thought the economic consequences were going to be more severe than they turned out to be. I thought supply chains were more fragile than they turned out to be. There are a lot of worst case scenarios that didn’t come to pass and thanks be to God and that’s good on the whole. But, I didn’t foresee how totally these two ships would go in different directions from the dock. And, I think it’s actually creating just massive vulnerabilities that we are not aware of. So, that’s one thing I didn’t fully see coming.

Collin Hansen: Well, I’m glad you introduced our listeners to the K-shaped recovery. I was even thinking of V-shaped as sort of like on its other axis.

Collin Hansen: So, like the V-axis, you’re either down and then up.

Collin Hansen: But my view was the V-shaped ,flip it around and it just keeps going up.

Collin Hansen: For all kinds of people and just goes down, and down, and down for a lot of other people. I just had no idea that we’d have that kind of experience. It’s pretty scary Andy, as the weather has begun to change, I closely associate a lot of experiences with that climate. And, I’ve been trying to brace myself for some sort of traumatic experiences associated with smells and feels and things like that, because I can remember those early days, late nights on the porch with my wife talking about what happens when we have no food?

What happens when there are bodies in the streets and there’s just nobody to take care of them anymore? All these things were, if you’re reading some of the studies, especially come out of the UK were entirely plausible options that did not come to pass. And yet, that’s what’s so interesting, is depending on your expectations and your experience of it, it’s all over the place. There just doesn’t seem to be any kind of shared social experience with this, which I have to think has contributed to a lot of the turmoil that we’ve seen politically, racially and otherwise in the last year. Another theme, Andy, from the March 20 article is that we’re all startups now and what you guys specialize in at Praxis.

Andy Crouch: Congratulations, you’re an entrepreneur.

Collin Hansen: I know. Exactly. And, certainly at the Gospel Coalition, that was part of the mode that we tried to transition into. And, you wrote this today, “From today onward, most leaders must recognize that the business they were in, no longer exists.” “This applies not just for-profit businesses, but to nonprofits and even in certain important respects to churches,” end quote. Andy, do you have any churches in mind that have managed this transition, especially well?

Andy Crouch: Ooh, interesting question. As with many things in American life, even before the pandemic, there’s this idea that gets thrown around a lot called the barbell economy, which is the idea of two kind of prosperous ends, the very small and the very large are the kinds of businesses in American life that have been thriving for quite a while. And, I do feel based on… My knowledge is only anecdotal of this, but I do feel that some really well-resourced large churches have at least in terms of… I mean, they’re kind of like the one half of the K, the K that actually has the sort of wherewithal, the momentum to pivot, has the media savvy, because of course, everything is always and only mediated now. So, if you’ve got great production values and people can tune in anywhere, why not tune into your high production value presentation, let’s say?

I think the other end is that churches that are small enough to do a new kind of intimate fellowship, worship and discipleship, and have not tried to just point a camera at the pulpit in an empty sanctuary, and press play every Sunday or every Thursday, the ones that have really pivoted to say, “Look, let’s just all get on Zoom, let’s go through whatever liturgy or worship we do, but let’s major on connection,” those have done well. The problem is that Zoom, which is our de facto medium, that we’re all using now, there’s no reality between 12 people on Zoom and 12,000 people on Zoom. Once you have more than 12 people on Zoom, you cannot attend to what’s happening in the lives, the emotions, the faces, the bodies, the experience of the other people. It becomes broadcast.

So it’s the middle, which obviously is the great majority of churches who I see really struggling, because they’re trying to put on a show, they don’t really have the capacity to put on, they didn’t pivot quickly enough to really small groups. I mean, the other thing that’s happening is the definition of small changes, because in the flesh, I think about 12 people, you can have 12 people in a room and really pay attention. But, if you want to really be heard and hear, and engage in the deep conversations with one another, and in a sense, practicing the presence of God together, that you do in a small group. On Zoom, I think it’s more like four to six max.

And, I just feel like… Unfortunately, I feel like most congregations just sort of were deer in the headlights. They got their worship online, but what we seem to be seeing, my friends at Barnard are studying this much more carefully than I’ve had time to do, is a significant fall off over time. And, how many people are able and willing to show up for one more Zoom thing, especially families with children. There’s just a huge attrition going on, because we didn’t realize the only thing that works is either massive or micro.

Collin Hansen: It squares with my experience, Andy. I have pretty large church, 1500 members or so. And in terms of our bottom line, never better, because we have so many people who gave money continuously. A lot of them were professionals whose jobs were not harmed and our expenses dropped off the map.

Andy Crouch: Right.

Collin Hansen: So, great… Never been better financially. Closer than ever with my home group, because we can be outside in small groups together. Only regular group of people that I’ve seen, I mean this entire time.

Collin Hansen: Yeah. So, closer than ever before. And, I haven’t been traveling.

Andy Crouch: Yeah. Yes.

Collin Hansen: So, normally I’m gone, at least this sort of the time.

Collin Hansen:

That’s sort of the time.

Andy Crouch: Right.

Collin Hansen: But everyone else I knew in the church basically disappeared from my life.

Andy Crouch: That’s right. And the sociological ramifications of this are going to play out for decades, literally, because there’s a very, very famous paper in sociology called, I forget the exact title, but it’s basically the power of weak ties, that’s kind of social health and flourishing, and what sociologists sometimes call agency, or sense of your ability to act and make a difference in the world. Turns out, we all of course think of the value of strong ties; our family, our closest friends, your home group would probably be a strong tie. But it actually turns out that for people to really have a kind of social mobility in the world, by which I don’t necessarily mean moving up economically, but just have a sense that they can get things done in the world and that they matter in the world, that weak ties are what matter a great deal. And that’s what falls out when you go massive and micro is, you no longer have those informal connections. Every couple of weeks, you see that person at church, you say, “Hello,” those are actually surprisingly valuable, important interactions for the kind of health of a community. And that’s what’s, I mean, I just don’t know how we could have maintained those, and in fact, I think those things are the things that are really eroding right now.

Collin Hansen: Yeah. It was something that we wrote about at the Gospel Coalition, some time back, just the people who were your, “I see you on Sunday morning,” friends. You wouldn’t have thought of it as being that big a deal. But when it’s gone, it’s huge.

Andy Crouch: Significant. Yes.

Collin Hansen: Lot of people who were very important to me. I didn’t realize that that was our point of contact. Just didn’t have another point of contact there, but continuing on this theme, Andy, when it comes to online church, would you say that COVID-19 either one, accelerated and inevitable trend toward virtual worship, as many pundits have predicted, or two, did the reverse’ showed us how inferior virtual worship is to physical embodied fellowship?

Andy Crouch: It probably, can I have both.

Collin Hansen: You’re going to go with both, aren’t you?

Andy Crouch: Because I think it’s going to be really interesting to see what happens. So to draw an analogy from another very related world, the world of higher education, my daughter’s a college student right now, and what she reports is she and her fellow students who have been able to actually go back under very strict conditions of course, and be in class in person to some extent, this semester, she says her fellow students have never expressed so much gratitude for what it means to sit in a classroom with other students and a teacher and have that experience. And they’ve never more dissatisfied with zoom and mediated instruction. And so, I think that everyone has realized how much being together matters, how much, not everyone would put it this way, but ultimately how much bodies matter; we’re heart, soul, mind, and strength, we can’t divorce, our spiritual lives, even our mental lives, our emotional lives from our bodies. And we mediate our presence with one another through our bodies.

So, I think we’ve discovered that. However, I will also say, if I have to pick one of your two, I choose the second option because I don’t think virtual church is going to work long-term, and we’re already seeing, I mean, we’re seeing so much attrition now, except for maybe the most effective communicators. And it’s kind of like the newspaper world; you’re going to end up with two or three winner take all media organizations, and all the others are going to disappear. And I’m not saying there won’t be really, really kind of amazing quote unquote, kind of the hill song of virtual church will shortly arise. It won’t probably be [inaudible 00:20:13], it’d be somewhere, we haven’t heard of that just nails that experience for people.

But it’ll be very thin, because I do not believe you can form people through media. I don’t believe media are formative. I believe relationships are formative. I believe relationships are embodied. And I think what’s actually going to happen is people are going to be hungry, not actually for intimacy, but for sensation. And I don’t mean sensation as in sensationalism; I mean like bodily sensation, like the feeling of being in a crowd, the feeling of getting out and doing things. We’re going to have the roaring twenties, but the roaring twenties were not a time where churches roared, right? The roaring twenties where the aftermath of the Great War and the Spanish Flu and had all the constraints of that era, and it was this time of sensate exuberance. It was a wonderful time in some ways for the arts, the Great American Songbook was written in the writing of twenties, the [inaudible 00:21:16] Renaissance, Paris, right? So not all bad, a certain kind of flourishing, but the flourishing of depth, of discipleship, of formation, that didn’t happen. And it actually set up massively unstable social conditions that we then had the thirties. So I expect a roaring twenties where we see a really dramatic shrinkage in affiliation with church, because it’s not going to be the kind of togetherness that people are desperate for, I’m afraid. And then I also expect the thirties to arise.

Collin Hansen: Oh, so we’re getting better here, Andy. I can see the ice age is really going well for us here. I mean, I-

Andy Crouch: Honestly, I mean, a lot of leaders listen to this podcast. We have got to be prepared for the kind of cultural catechism that happened to Europe after the Great War. And I think most people think, “Oh, how much longer till we get back to normal?” No, whatever health comes out of this 30, 40 years from now institutionally or otherwise, it’s going to look utterly different from what we knew in 2019.

Collin Hansen: Yeah. I got a book coming out in August, Rediscover Church Where the Body of Christ is Essential, trying to prepare leaders for that because, I mean, I’m sure we’re seeing the same numbers, about 33% of people have disappeared from church since March. Name of bigger disruption one-time disruption in, in church history. And I’m sure there is one, I’m just trying to go back. Are we talking about-

Andy Crouch: The Black Death.

Collin Hansen: I was going to say, I literally was going to say the plague. I just read [Barbara Tuchman’s 00:22:59] book on the 14th century just like, reading about the plague. That seems to be what we’re looking at here, which is when a quarter was a quarter of Europe’s population died, something like that, or a third, I can’t remember, but that’s, I think we’re looking at.

And I think so you could apply the church thing to then the workplace, and I’m sure that’s a big deal for Praxis folks and all that kind of stuff. I think what I’m seeing in general is that at first people thought, “Oh, this is great working from home. It’s wonderful.” And then I thought, “Oh no. No, this is not good.” But what they never said is, “We’re going back to what it was like before.” So speaking with somebody in my family, she’s got two kids, commuted for a big job in a major city. The one thing I know is that she’s never going back to the office five days a week. She wants to go back to the office sometimes, but she’s never going back five days a week. So I think we can probably conclude right now, Andy, that no, we’re not all going to work from home forever. I don’t think any workplace, if you can avoid it, will ever go back to five days a week. So again, there’s no chance for turning back the clock to 2019.

Andy Crouch: That’s right. And I would just footnote that, that’s true of the upper half of the K and I mean, and there’s a lot of people God loves in that upper half of the K, and that’s us and our lives matter, but let’s just remember that people who will continue to obviously go to work, because their work is physical, right? It can’t be displaced, and they are going to be under even more stress and pressure. They also are not going back. Not that life was great in some of those conditions before, but it’s just going to ratchet the pressure up for-

Collin Hansen: I just think a lot of those jobs aren’t going to be there anymore. They’re just never coming back, that’s what I’m concerned about with that group. So I was saying either way, so we could definitely say that, “No, virtual church is not going to be something that everybody does.” A lot of churches are going to turn off their live streams when they can get back, but never before will people think about, “I have to go to church.” They’ll never think that way again. From now on, they will always think, “I’m sure there’s a different church I could watch somewhere if I really feel like it today.” So I think it’s a permanent disruption in that, and we’re just not going back. And the virtual church is now a full-blown competitor to every single church in existence.

Andy Crouch: I suppose you are right. I’m just not sure virtual church can compete with virtual everything else that people can spend their time on, and get a sense of meaning from, get a sense even of a spiritual encounter from, you know? You see what I mean? So-

Collin Hansen: Yeah, there might be a bridge to your, sort of like an off-ramp.

Andy Crouch: Yes, that’s right.

Collin Hansen: It’s an off-ramp, virtual church is like an off-ramp deescalation from ’19.

Andy Crouch: I think that’s right. But I will tell you the people who are suffering, I mean, I don’t know, can we categorize this? There is a notable group of people suffering right now from virtual church, and the most dissatisfied that I hear about consistently are children and teenagers. They do not like it. They don’t want it. I have friends whose children have just refused to go to sit on, watch the Zoom thing. I have a friend who is a leader of a major ministry who was doing his best to disciple his kids, and they said to him, “Dad, didn’t you teach us the church is the body of Christ, interdependent?” And they said, “What are we doing? What we’re watching is not the church. Everything you’ve taught us.” He’s like, ” Yeah, you’re right.” So, I really like your off-ramp and I don’t like it, but I think you’re offering an LG is apt because for people who have the habits, this is a way of not feeling guilty that they’ve totally ditched the habit, but it’s not going to lead them into deeper engagement. And then the kids who don’t have the habit, they’re never going to acquire it. They’re never going to pick it up. Yeah.

Collin Hansen: At one point with my own church, I just had to decide that even though I didn’t love the idea that we were meeting outside in a parking deck, which we still are, that just going with my kids was the necessary ritual. I could not afford to let it sink into their minds that church was sitting at home while they don’t pay attention, just another random thing. Because the screen that they’re looking at is the same form of entertainment, so already the is shaping their entire expectation of what they’re getting. And so, it’s purely a consumer thing, but it doesn’t really appeal to them as a consumer thing, not compared to anything else that they could be doing. And so I said, “Okay, forget it, we’re going to the parking deck. We’re going to do this.” And so now my three-year-old daughter, the other day, she pointed into a parking deck and said, “Do they have church there too?” Because she just thinks parking decks are churches now. She’s not old enough to remember a building.

Andy Crouch: Wow. “The city is full of churches.”

Collin Hansen: Full of churches. I mean, you’re right; for children, I don’t think we have begun to scratch the surface of the effects. Andy, you also cite, maybe we will come back to that one.

Andy Crouch: Isn’t this hopeful?

Collin Hansen: Yeah. Well, you say, “Trust as the prime virtue available to us by the grace of God to endure the pandemic,” is what you wrote a year ago, said this, “All the efforts of leadership right now come down to maintaining and mobilizing trust. This trust begins not with concern for ourselves, but with concern for others.” Andy, I don’t think things worked out that way inside or outside the church.

Collin Hansen: Here’s my basic question: why didn’t COVID-19 pull us together? And you ask a haunting question, you wrote this on March 12th, “When this plague has passed, what will our neighbors remember of us?” It just seems that especially in politics and racial justice, the pandemic created conditions that he wrote it, and in some cases tour our social fabric. I have seen some evidence that there was some pulling together on COVID until George Floyd’s, and then things really started to pull apart, on COVID and everything else. So yeah, just why didn’t it pull us together?

Andy Crouch: Our institutions were already very fragile. So there’s this famous line from one of Hemingway’s novels, “How did you go bankrupt?” And the answer is, “Gradually. And then suddenly.” We were already gradually losing trust in our institutions, whether that’s urban communities trusting the police, whether that’s Americans trusting their leaders, so forth. So they were already weak. Frankly, a police force that does not have a better way of handling an uncooperative suspect, and it can’t train its members to honor people, even they carry out the necessary work of keeping the peace is, very vulnerable. And especially vulnerable in the age of media. I mean the truth is policing is more fair and better today than it’s probably ever been at the average, but when you capture a moment, that is a dereliction at the very least, of the duty to serve, honor and protect, that’s really damaging. So I would say the second thing is media is an amplifier of the worst in all of us.

We fixate on the things that cause us the biggest kind of spike in stress hormones and blood pressure and so forth, is what we can’t look away from. And so everybody’s mainlining into their limbic systems, anxiety, fear, outrage, everyone has faces to attach to the people they should distrust and be afraid of. It’s not even ideas; it’s faces that look really angry and look really threatening, and that’s true, no matter which side of whatever issue you’re on.

Andy Crouch: …No matter which side of whatever issue you’re on. And then we had leaders who failed us. I think. I mean, I’m thinking individuals it’s weird how even whole massive nations come down to the character of persons. You just can’t get around the character of the person entrusted with a given moment. And whether it’s Anthony Fauci who very candidly and carefully tries to say that we don’t really need masks because he has a lot of considerations in mind that he doesn’t really want the public to know about in March of 2020 but that backfires tremendously.

Collin Hansen: I’m still dealing with that backfire.

Andy Crouch: Absolutely. So I mean, you could just go down the list. So, it’s very rare that you have the right leader at the right time unfortunately and there are a few moments that have rescued our country. I think Abraham Lincoln’s presidency was a moment. I mean, it came at a horrible cost but that cost was going to have to be paid as near as I can tell somehow. But we ended up with a United States after the dust settled and the bodies were buried because of the leader who was there in that moment. If it had been Warren Harding or Garfield or God forbid Andrew Jackson.

Collin Hansen: Buchanan who came right before and precipitated the crisis.

Andy Crouch: Right. Right. You know your American history better than I do honestly. But and then in the 1960s we had Martin Luther King Jr had a kind of gravitas that was needed for that moment. And LBJ for all of his craziness was able to work with MLK and saw the importance of it and was willing to lose the south for the democratic party for a generation. So, we didn’t have that this time. And you pray that Caesar will be the Romans 12 Caesar which is it 13?

Collin Hansen: 13.

Andy Crouch: Wielding the sword against evil, restraining evil. Obviously pray for Caesar to act that way and some Caesars do but some Caesars don’t and then you live with a really broken world and that’s where we have been in the last many years in America.

Collin Hansen: You definitely can’t study history without seeing the significance of the leader’s character and abilities. I also, I wonder about this Andy, this is one of your areas of expertise as well. There’s no chance we’re able to endure the pandemic in a lot of the positive ways we’ve talked about here without the media revolution that I would really attribute to the broader iPhone revolution essentially because that’s what unleashes everything from the podcasts to streaming services to all that different stuff of course. And that’s one reason why the pandemic for at least many people was not some kind of seismic shock because of their work, facilitated by Zoom and all that kind of stuff, but then also because of the endless entertainment.

Andy Crouch: Which was so good for us.

Collin Hansen: We could have 30 pandemics and I wouldn’t get to the bottom of all of my streaming services. It’s just stuff, it’s endless things churning out. At the same time, it’s precisely why the pandemic was so threatening to us because of how it facilitated these terribly negative experiences with each other and with our surrounding environment. And so, I guess that’s just the story of media, new technologies, it gives and it takes away and you take the good with the bad and you can’t really separate it. You can be discerning about what you should adopt and not adopt but that’s I mean every new technological innovation is going to give you something but when it gives it’s going to take something away too.

Andy Crouch: Well, and these innovations don’t stay where we put them. That is to say …

Collin Hansen: … little intended box.

Andy Crouch: Exactly. I think the creep of media into all of our lives, of course media above all through the smartphone, when I check Twitter once every day given that I curate relentlessly who I follow and all that, but it’s helpful. I learn some things, I find some interesting new people I hear from voices I might not hear about in any other way. When I check Twitter 12 times a day, that’s not as good. It’s not 12 times as good that’s for sure. But all the incentives of course, and we know all of how this works psychometrically and so forth, it’s all designed to get me on the 12 or 24 or 48 a day rhythm.

And the truth is I don’t think the fact that we had Netflix has helped us one bit, I don’t think it’s helped us one bit. We were all on screens more than ever in our lives. The last thing we needed in our rest, the hours that should have been rest became hours of leisure. I like to distinguish those two. I just, I think we’re made for work and rest. We end up in the conditions of the fall with toil and leisure and leisure is this empty, it’s empty, it’s vacant, vacant vacation. It’s letting other people do the work for you of giving you a sensation of being alive and that’s very different from rest. When I’ve had a hard day’s work and then I sit down at end of the day or maybe I’ve prepared a meal for my family that’s work but then we sit down and we enjoy the meal and we linger over the meal that’s rest.

But that’s really different from ordering takeout. And we all got a diet of media takeout at the moment when we all should have been, some people were baking bread, knitting, walking, take up rock climbing. And to the extent that we did those things this was a great opportunity. But to the extent that all of us found ourselves numbed into just keeping the media feed going even when it felt like entertainment, even when we weren’t getting mad at people on Twitter or Facebook or whatever I think it was actually really misshaping us and not good for us.

Collin Hansen: Andy, I love how you described leadership in your March 12 article. You said this, “A leader’s responsibility as circumstances around us change is to speak, live and make decisions in such a way that the horizons of possibility move towards shalom flourishing for everyone in our sphere of influence, especially the vulnerable.” Why does that kind of leadership seem so threatening to so many evangelicals who prefer the anxious agitated leader?

Andy Crouch: Oh my.

Collin Hansen: You’d think Andy that we would love this. We don’t choose it.

Andy Crouch: That’s not what we wanted.

Collin Hansen: No, these are not the leaders who have emerged through the crisis. The leaders that have emerged through the crisis have been the anxious agitated leaders.

Andy Crouch: I have to think, I do not know the answer to your question Collin. I mean, it goes back to Corinth at least Paul uses this Greek term the hyper apostles, the impressive ones are coming through. And he’s like, “I can’t compete with those guys. They studied rhetoric and I just picked it up secondhand.” He knows they’re impressive physically, he’s not. He seems to perhaps what we would today call a disability possibly. Not that Paul didn’t have power and forcefulness he could deploy but he wasn’t like those hyper apostles and the Corinthians were really impressed.

So it’s not a new thing. I do think, I think media, especially visual media, especially actually small format visual media. So the smaller the screen the tighter the shots. So when you watch a feature film the cinematographer at least can choose to give you a quite wide picture of the world and incidentally your eyes scan when you’re in a theater…. Remember when we used to be in theaters with big screens and your eyes take in a horizontal field of view? When you strip that down to a vertical little screen everything’s close up, all context is removed. It’s a very intimate thing to encounter another’s face actually with a level of resolution that you would only encounter your spouse, your children at that distance and that close up. The tight one shot as they call it in cinematography. I don’t think this is good for us and the leaders who are really good and the emotions that translate really well to that medium which also requires you to be really quick so it’s easier to be anxious quickly and outraged quickly and high energy in a way quickly, it’s harder to be patient quickly.

I mean, imagine just to pick one of my heroes, he wasn’t perfect but he was a godly man, Eugene Peterson, imagine him on TikTok. It’s not going to work. He goes too slowly. He’s thinking about things. And this is just a spiritual giant. I don’t know, was he a Saint? I don’t know. But the grace of God was at work in his life. His life bore incredible fruit. But could it translate into a mediated environment? Not at all. And so I don’t know if it’s what we want, I think you asked why do we prefer, but I think it’s what medias select for us.

Collin Hansen: Okay. Yeah. Two forms of the mediated personality that I’ve seen really stand out and they signal trust and insight. They are the person sitting in the car being filmed on their phone looking adjacent to the camera, not looking into the camera. The other is the young, fast talking man staring into the YouTube format camera who’s giving you the real story. It seems like those are the two forms of media that like I said communicate trust and insight that a lot of evangelicals have gravitated toward. So you’re saying it’s really, it’s about the media that rewards that?

Andy Crouch: Yes and I think it’s the screen. I think if you printed out a transcript of what they’re saying and ask people to read it and gave people the skills to read and just experience primarily reading it would be different. I think these visual media have beautiful things to contribute to the human experience. I’m not anti visual media at all. I am not sure they’re the best place to find out the truth, the facts. Be aware of facts, facts are complicated. Facts are interpretation laden. But so someone who says, “I’m going to tell you the truth, the facts,” that should set off alarm bells. Because actually getting to that level of truth is not easy and is better done in writing and is better done when you can reread and when you can compare than when you’re just watching a stream of video. Video is good at other kinds of truth, it’s good at emotional truth, it’s good at beauty, lots of things that words can do but video can also do. But yeah, we’re in a bad, this is bad.

Collin Hansen: Well I mean, there is hope. I mean, I am discouraged by a lot of different things. One thing I’ve noticed is that even for close friends of mine, colleagues in ministry, people I’ve known for more than a decade when somebody does that kind of media that I just described in this environment they naturally think that person is true and that I am wrong. I also find in this climate that…

Andy Crouch: It’s rhetoric, it’s the gift of persuasion.

Collin Hansen: Yeah. So, there’s something about when that video clicks in somebody automatically thinks, “I can trust this. I don’t know the person, I don’t know the truth, I don’t know the facts, but somehow it communicates a kind of intimacy and a trust there.” And yet, because there’s no institutional authority there’s no credibility that can supplant or respond to that. And then you look at the kind of degradation of our institutions broadly speaking, I think what we’re seeing across the board with churches is a growing affinity for that kind of media as the real story that your pastor, your leaders don’t want to tell you. And then because you’re not seeing them in person you lose whatever kind of advantages come in. So, this is part of your ice age. I don’t know exactly how we go back to this but I know for sure that the 12 to 18 month window will reshape our churches such that they will never and can never go back to that because something fundamentally has shifted in there.

But there is hope, you guys wrote this heading Easter back last year, we’re heading toward Easter again praise God. Easter is also an everyday occurrence, the course of our lives, the risen Christ. But your team wrote beautifully about the grief of Calvary and the hope of Easter. We’ve really talked a lot about the grief of Calvary which I think is significant. Andy, how has God sustained you during the ice age?

Andy Crouch: Yeah, that’s interesting. I mean, so we are talking about some really alarming trends and they are real and they are really, I mean when you stare directly at them they’re scary but I have mostly been very hopeful. I’ve had some of the most meaningful discipleship experiences of my life in the last year. I’m part of a little group that meets every other Monday night, folks I hadn’t met with before the pandemic. I barely knew one of them at all, others I knew to some extent. And we’ve had just amazing encounters with one other as fellow followers of Christ. So actually I’ve been amazed at how the Holy Spirit can work through Zoom.

Collin Hansen: That’s a Zoom thing.

Andy Crouch: … how the Holy Spirit could work through Zoom.

Collin Hansen: That’s a Zoom thing you’re saying.

Andy Crouch: Yeah, yeah. That’s a Zoom thing. These are folks all over the country.

Collin Hansen: Okay.

Andy Crouch: All over the country.

Collin Hansen: Again, I’ve heard that from other people as well. All of a sudden the idea of a small group suddenly begins to extend to, “Wait a minute. I didn’t realize how easy it would be for me to be able to just gather a group of friends together and just pray for each other.”

Andy Crouch: Totally. And that’s exactly what we’re doing. It’s been just very surprising how much of a gift it’s been. I wouldn’t want it to replace the local church, mind you. But it’s a meaningful thing. One of the things that sustain me is my daughter wrote a book called My Tech-Wise Life that we got to promote this past fall and winter and just doing events with her and seeing her as a 20 year old and her friends and how they are pursuing God, how they’re pursuing real life. How her life is really a beacon to friends who may not know God in the way that she has been claimed by God. And I’m just really encouraged by that honestly.

So I’ve had two six-week periods of despair, just to be clear, in the last 12 months. Two times where I just felt like the gears were grinding and I could hardly get out of bed.

Collin Hansen: Where did those two things come chronologically?

Andy Crouch: July and January.

Collin Hansen: July and January. January was bad. January was bad.

Andy Crouch: I will tell you after January 6th, was that a Thursday I think?

Collin Hansen: Wednesday.

Andy Crouch: Oh, it was a Wednesday.

Collin Hansen: My son’s birthday.

Andy Crouch: Oh. That weekend, just to tell you the truth, I went to bed Friday night at 7: 30 PM and I got out of bed for a total of two hours until Monday. I talk in one of my books Strong and Weak about the withdrawal response to suffering, and I could not move. I was so grieved. I felt so impotent. I felt like such a failure to shape anything in our country, and I just slept and slept and slept. I really was asleep the whole time except for those couple of hours each day. Those were bad. And there was some other moments like that in July and January. But then my friends like come along and lift me out of it and grieve with me. I think actually the most helpful thing has been having people to lament with and grieve with and have other people who are also going through really difficult things, much harder than I maybe going through.

I feel like what is gold, silver, and precious stones in the church in North America is not going away, and it’s so real. And I will also say the work at Praxis, we work with entrepreneurs. They’re very resilient. They’re very creative, entrepreneurial, obviously. The level to which our community has been able to rise to the challenges of the pandemic and the courage that they’ve shown. Some of our organizations have grown to be pretty big and multi-million dollar companies. But a lot of them are still small. The courage they’ve shown in showing up to work and figuring out how to keep people employed and how to even grow there businesses. And I get to work every day with just the opposite of what you see on TV and what you see on social media in terms of faithfulness, discipleship, depth, redemptive intent. And so that’s kept me more than going honestly. I feel great, great hope.

If Dietrich Bonhoeffer could do it with 15 guys that think of all the… Across the lake from a Nazi military installation, I think I can manage to hope that God is still at work in the United States during COVID-19 Ice Age.

Collin Hansen: That history does give perspective. For listeners who want to know more about this, go check out Sarah Zylstra’s piece that we published not long ago, Changing Lives Through Washing Cars featured the Praxis Group.

Andy Crouch: It’s a beautiful story. It’s so, so good.

Collin Hansen: It’s great. Andy and I are both journalists. We’ve been around the block a number of different times in this world, and one of my commitments, and you’ve been an encouragement in this, but one of my commitments is to go out of our way to tell good stories, tell positive stories of God at work because it just doesn’t come natural to us as journalists. It’s not how we’re trained to think, which is part of why … gone the way that it’s gone.

So we’re natural analyzers. We’re natural obsessers. You learn to be skeptical at different things. It’s necessary to survive in this profession, and it’s an important calling as well.

Andy Crouch: That’s right.

Collin Hansen: But you need to ground yourself back in, “God is at work. All I’ve got to do is look.”

Andy Crouch: Totally.

Collin Hansen: Just got to look for it. Sarah and I, and this is part of our bigger initiative with our book Gospel Bound: Living With Resolute Hope in an Anxious Age, just trying to tell these stories. Help remind people this is what God’s doing. He’s doing all kinds of different things, including all this god stuff. Just a couple more questions here with Andy Crouch.

Andy, what did you learn in the last year that you should’ve been doing all along and that you never want to stop doing?

Andy Crouch: I don’t know if I can keep this up. But every day the temperature was above 55 degrees for months at a time, I was out on my bike for 20 miles.

Collin Hansen: Oh, wow.

Andy Crouch: Which I loved biking my whole life, and this is not a new 20 mile ride. It’s the same ride every day. I’m a total creature of habit. I have no interest in novelty when I get on my bike. I want to ride the same path and see if I can do it like 30 seconds faster than my median time. Doing that every day though, like you mentioned being away a third of the time, that’s been about my pace for many years. Suddenly I was home every single day and for long stretches of time in Pennsylvania where I live. Every day I could go out on my bike. Oh my goodness, it was so good. It was so good. It just in every way. The smells of the air. The wind. The work of my body. The quiet. The aloneness, solitude I guess you would say. Man. Normally that gets shoehorned in on a nice day between a lot of travel. So that was great.

So with careful attention but also in gospel freedom let’s say to the law about travel, the only travel I did was to my parents’ home. My parents are in their 80s. And being very cautious, truly. I’m getting tests, and we observed the law and do to this day. I started visiting my parents who live five hours away from me. First every other weekend in the spring, and then more often in the fall and winter. My dad actually has just been diagnosed with a very serious, challenging condition. And actually we’re doing this podcast. I’m at their house this weekend.

I’ve been with my parents more than ever in my adult life. And my goodness, it’s been the most wonderful thing. So it’s to some extent for a season. It’s to some extent because of urgency and the need for it for sure. And I will have to stop doing that because they won’t be here forever. And in the days that I can do this, the chance to read the commandments and think, “Actually, honor your father and mother, I think I’m actually doing that right now in a way that honestly I’m not sure…” My parents would never probably say that I haven’t honored them. We’ve had a very loving relationship, but I’ve honored my father and my mother during this time. It’s been really a gift to get to do it, and I know many people haven’t been able to do that. So I hope that doesn’t cause distress to others who haven’t been able to do it that way, to honor them that way. But for me, it’s been very meaningful.

Collin Hansen: Yeah. I don’t see any way Andy, where I’ll ever see my kids more than this last year. I don’t think that’ll ever happen. Their own activities. They’ll leave. My travel, all that. It just won’t ever be that way again. I set a goal early on in my family that I wanted my kids when they remembered this time, and they would remember it. I wanted them to remember it as maybe one of the best times in their lives. I didn’t want them to fixate on all the things I knew they would lose. My kids are younger. So there’s a lot of things they didn’t have to worry about there. I wanted them to remember all the things that they gained. And a lot of that God willing, praise to God, because of my job and things like that, I was able to do for other people that hasn’t been the case, and we mourn for that, especially with loss, the death just to begin with. But I’m grateful for that.

On a lighter note, shout out to the wifi at your parents’ house. I’m kind of shocked how good it is.

Andy Crouch: I may have upgraded it.

Collin Hansen: Okay. I wondered about that, Andy. I was like, “Wow. For parents in their 80s, they really have some qualify wifi.” Okay. Last question, but there’s a landline phone.

Andy Crouch: Yes, they do, which I thought was unplugged.

Collin Hansen: Oh, that sounds more like it, Andy. Before we close off with the final three, you’ve alluded to this already, but you spoke, you and your team, you personally with Praxis team spoke with remarkable impressions on March 12, 2020. What’s your message for us today? You mentioned the 30s coming. Anything you want to add or expand to that?

Andy Crouch: Keep learning, keep changing. Don’t think we’re going back. Don’t stop redesigning for what’s real now and what you can see of what’s coming, which is not much. We still at Praxis, we’re on a kind of three-month horizon. We’re not trying to plan beyond that for now. Don’t be fooled by the roaring ’20s. And make disciples. Make disciples, please. Would someone out there index everything you do by the question, are these people living a transformed life? Where did I read? I forget who it was who said… It was George MacDonald who said, “If you cannot look back at the end of the day and say, ‘I did something today only because I believe that Jesus Christ is Lord,’ or, ‘I did not do something today. I reframed from something today only because I believe Jesus Christ is Lord.’ If you can’t say that, what are you doing?”

So please, let’s just realize the only thing we really leave behind in the world is transformed lives and by the grace of God, the fruit of our lives can be other lives that are different and that’s the only thing. That’s certainly the only thing that’s going to survive the winnowing of the next few decades I think.

Collin Hansen: That’s what I was going to say, that winnowing. If we lose 33% overnight from the church in something we haven’t see in perhaps many, many centuries, it doesn’t have to be the death of the church. It can be the purifying of the church in refocusing on those first priorities if we’re willing to wean ourselves off many of the things that we unfortunately have turned to in 2020.

Normally, Andy, I ask final three. But a couple of them that I have in here, what brings you calm in the storm, what do you find good news today, you’ve already answered I think. So we’ve covered those. The last one within in the final three is what is the last great book you read?

Andy Crouch: It is re-reading. I’m re-reading Watership Down by Richard Adams. Strangely mislabeled as a children’s book because it has talking animals. But not at all children’s book. Not a complicated book. The thing that I didn’t see in it the last time I read it, which was probably 20 years ago, if not more, is he knew the natural world in this beautiful way. And he has these descriptions of what it’s like to be an animal out under the sky and just the names of all the plants and flowers and all the things a rabbit would pay attention to. It’s bene good. Watership Down, it’s worth revisiting every 20 years.

Collin Hansen: I’ll take it. My guest, my gracious, gracious guest on Gospel Bound has been Andy Crouch of Praxis. Check out their work. You can really anticipate what else you’re going to be writing and helping us to know the future. Failing knowing the future, helping guide us in how we can be faithful in whatever the future has in store.

And just a personal note, Andy, just a thank you to you for all your encouragement, support, being a role model for me in a number of ways over the years. Going all the way back to my early days of Christianity today. Began our transformation culture stuff and all of that. I appreciate that. But just thank you for the wisdom you always bring, which feels marinated in the whole spirit and in God’s word. It means a lot to us during these hard times. Thanks, Andy.

Andy Crouch: Thank you.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.Collin Hansen serves as vice president for content and editor in chief of The Gospel Coalition, as well as executive director of The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics. He hosts the Gospelbound podcast and has written and contributed to many books, most recently Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation and Rediscover Church: Why the Body of Christ Is Essential. He has published with the New York Times and the Washington Post and offered commentary for CNN, Fox News, NPR, BBC, ABC News, and PBS NewsHour. He edited Our Secular Age: Ten Years of Reading and Applying Charles Taylor and The New City Catechism Devotional, among other books. He is an adjunct professor at Beeson Divinity School, where he also co-chairs the advisory board.

Andy Crouch is partner for theology and culture at Praxis, an organization that works as a creative engine for redemptive entrepreneurship. Crouch served for more than ten years as an editor and producer at Christianity Today, including serving as executive editor from 2012 to 2016. His work and writing have been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Time.