Medical missionary Rick Sacra has been evacuated three times—all from the same place.

He’s spent a career at a mission hospital in Liberia, leaving when he’s in physical danger and then returning again and again—after civil war, political unrest, and Ebola epidemics.

If you ask why he keeps going back, he’ll laugh and tell you he’s stubborn.

But it’s more than that.

“When something happens to the people you love—as hard as it is to be right there with them, it’s even worse to be far away feeling helpless,” fellow missionary and longtime friend Dave Decker said.

It’s the emotion you feel when your child gets sick at school, or your sister in another city gets into a car accident. It’s how you felt if you were out of the country when the planes hit the World Trade Center. It’s what made Bonhoeffer return to Germany, what made Gandhi head back to India.

It’s like that, but not quite. Because Rick was born near Boston. He went to college in Rhode Island and medical school back in Massachusetts. He married a girl from Florida. If anything, his home was on the East Coast.

“During the war, when ELWA Hospital had to close temporarily, the Sacras followed the Liberian refugees to Côte d’Ivoire and ministered to them,” said fellow medical missionary Jon Fielder. Fielder’s organization, African Mission Healthcare, awarded Sacra the Gerson L’Chaim Prize for Outstanding Christian Medical Service this past October.

“Think about that for a second: The Sacras could have—very reasonably—decided to return to the United States? Their hospital was closed, the patients gone. They could have gone to a more stable part of Africa. Many places need doctors desperately. So why follow Liberians to another country?”

Boston to Monrovia

Rick grew up in a Congregational church in the Boston suburbs, attending Sunday school and vacation Bible school and youth group.

“A lot of missionaries would come and do presentations,” Rick said. By junior high, he knew he wanted to join them. He’d always ask the same question: “Do you need doctors over there?”

Because he wanted to do both. As a child he checked out library books on the human body, animals, and biologists such as Louis Pasteur and Alexander Fleming. In elementary school, he asked his dad about going to medical school. In eighth grade, getting his appendix out was the highlight of his year.

Rick never wavered from his goal—except for a brief moment of panic at Brown University when his professor told him his grades weren’t good enough for medical school. He dropped the rock band, moved to a room next to his “nerdiest friend,” and pulled his grades back up.

After college, Rick and his fiancée, Debbie, spent a summer in Japan with Campus Crusade (now Cru) to get the feel of overseas mission work. Both loved it, but they heard that almost everybody loves mission trips for a summer. To get the real experience, they were told, you have to stay for at least a year.

So the couple looked for somewhere they could serve for a year. They found a list of mission hospitals in Africa—the continent with the biggest health-care needs—and asked 10 if they could come for a year.

Everyone said no.

“Medical student blocks are eight weeks,” Rick said. Mission hospitals aren’t set up to take students for any longer.

ELWA Hospital in Monrovia, Liberia, also said no. The hospital was built in 1964 by SIM missionaries to support the community that had grown up around the first Christian radio station in Africa—call letters ELWA.

But the ELWA community also had an elementary school with about 150 kids, and they were looking for a junior-high social-studies teacher. And Debbie was a junior-high social-studies teacher.

“We knew nothing,” Rick told TGC. “We didn’t feel called to Liberia or anything. When we found out we could go, we had to go to the library and get some books to see where it was.”

They found out it was on Africa’s west coast—a country established by ex-American and ex-Caribbean slaves in the early 1820s, where economic development had been slow to develop, and where president Samuel Doe—who had gained control through a coup—kept power by crushing coups.

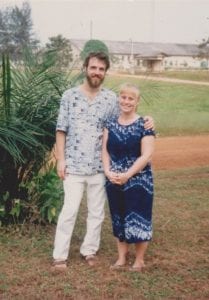

The Sacras spent the 1987–1988 school year in Monrovia, on a compound bustling with close to 70 missionaries—doctors, teachers, boarding-school parents, radio staff—and their families.

“We fell in love with Liberia,” Rick said. “We enjoyed the people, the culture—everything.”

Moving to Africa

After the 1987–1988 school year, the Sacras returned to the United States so Rick could finish medical school and residency.

Meanwhile, Charles Taylor (not the Canadian philosopher) launched one last coup against Doe. The president was killed in 1990, leaving a power gap Taylor and his rival warlords would fight over for another seven years.

“By the time we got accepted [as missionaries] by SIM in 1994, things had calmed down enough that they were re-opening Liberia,” Rick said. “We didn’t really think seriously about other options or visit anyplace else.”

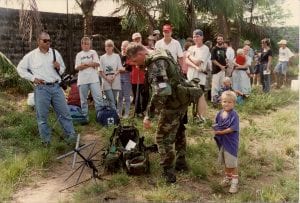

The compound they returned to looked very different. After two evacuations of staff by SIM, just a third of the missionaries remained. Buildings had been hit by mortar shells. The print shop was burned into rubble. The radio transmitter was looted.

“But there was a lot of optimism in 1995 when we got there,” Rick said. After all, a transitional government was now in power, so there was no need for more fighting. SIM was eager to rebuild.

But the Sacras—Rick, Debbie, and their two small boys—were only in Liberia for about a year when “everything fell apart again.”

Evacuation One

When the fighting erupted in Monrovia in April 1996, most international NGOs pulled their staff out.

“Leaving was excruciating, because the crisis wasn’t over, but it got so bad you couldn’t exist there and do what you were doing,” said Decker, who was flown out with the Sacras. “To have to leave people we knew and loved at their greatest point of need was excruciating like nothing else. As the plane or helicopter takes off, you expect a great sense of relief, but you never really felt that.”

Waiting in the United States was “frustrating and very uncertain,” Rick said. “We would’ve come back to Africa sooner, but Debbie was pregnant and had C-sections with our first two.”

Liberia’s battles calmed down in August with a treaty that promised elections the next year. The Sacras stayed in the United States long enough for Debbie to give birth to their third son, then hopped a plane back to Africa when he was 4 months old.

But they couldn’t return directly to Liberia, which was still leaderless and unstable. So they headed to the neighboring Ivory Coast, where thousands of Liberian refugees had fled. “A couple of us started coming back into Liberia for like 10 to 14 days at a time,” Rick said.

He did that for a year—while Taylor was finally voted into power by a country weary of violence, while SIM told ELWA that it couldn’t open up again after three evacuations in six years, while Liberians said they’d reopen the hospital themselves. Then he talked SIM into letting him serve at ELWA Hospital.

“I loved the hospital,” he said. “I wanted to help it succeed.”

And there was his stubbornness, which Debbie calls “stick-to-itiveness.”

“Rick is somebody who sticks with something until God makes it really clear there’s something else to do,” she said. “We just never really felt God was telling us to do something else.”

Rick moved his family back in June of 1998, to a campus with no electricity and no running water. “We’d send the janitor to the well to fill up barrels,” he said. “I’d scrub for a C-section with a nurse or aide pouring water over my hands. If you had to do a surgery, you’d turn the generator on.”

For several years, Sacra shared duties with missionary doctor Steve Befus; when Befus was diagnosed with lymphoma in 2000, Sacra was the only long-term missionary doctor on staff. He brought on a handful of Liberian doctors and discovered he loved to mentor them.

“I love teaching a younger doctor how to do a C-section, or take care of someone with heart failure,” he said. “I love transferring knowledge and skills to our residents.”

And for five years, Liberia was at peace.

“We live on the beach, literally,” Sacra said. “It’s a great place for kids—as long as there are no bullets flying around.”

Evacuation Two

In 1999, bullets started flying around again, this time in the countryside. By 2003, the rebels reached Monrovia at the same time Taylor was indicted by a United Nations court for war crimes he committed in neighboring Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war.

“ELWA was never in an area with fighting,” Rick said. But that depends on how you define “area”—the battles were “six to eight miles away. We could hear it.”

Debbie and the boys left; three weeks later, SIM pulled Rick out too. But the family didn’t leave Africa; they stayed in the Ivory Coast until Taylor resigned.

“We didn’t ever feel unsafe,” Debbie said. “We felt the Lord was protecting us.”

And he did. After the civil conflict ended, the Sacras settled into ministry at ELWA. New mission-team members arrived. Liberia’s lone medical school opened again.

“Those were truly the building years,” Debbie told TGC.

Can’t Stay Away

The Sacras moved back to the United States in 2010 and stayed for a few years, getting their boys settled in high school and college and taking a breather.

But Rick also “had the conviction I was supposed to start a family medicine residency program.”

The need was intense—after 14 years of civil war that killed 270,000, only 16 hospitals remained somewhat operational. Nine of 10 physicians had fled, leaving 90 doctors for a population of a little less than 4 million. The medical training system was in shambles; there had been no residency programs of any kind for 20 years.

So Rick balanced between two continents, settling into a pattern of working in Liberia one month out of three. (The low-income clinic where he works while in the United States is flexible with his hours.) He spent May 2014 in Liberia and was scheduled to return in mid-August.

That spring, cases of the rare and often fatal Ebola virus were reported in nearby Guinea. ELWA Hospital got an isolation unit ready in April, but the whole time Rick was there, it sat empty.

Ebola Strikes

On June 11, the Liberian Ministry of Health sent ELWA its first two Ebola patients. One died in the ambulance.

Over the next six weeks, Ebola raced across Monrovia. It spreads through contact with bodily fluids such as blood and vomit; soon, hospitals became the most dangerous places to be. Health-care workers who weren’t infected quit in fear and frustration. One by one, hospitals shut down.

“[T]he number of patients grew exponentially,” missionary doctor Kent Brantly told Time magazine. He was working in the unit at ELWA when he and nurse’s aide Nancy Writebol came down with the disease. Days later, another nurse was diagnosed. ELWA Hospital closed to decontaminate.

While the State Department worked on transporting Brantly and Writebol back to the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was warning off all “nonessential travel” to West Africa. (Overall, about 60 percent of more than 28,000 Ebola patients in West Africa would die from it.)

But Rick was already booking his ticket.

“My biggest concern was that all of the hospitals in Monrovia were closed,” he said. “We’ve got a capital city of a million and a half people and nowhere to go. If you get appendicitis, you’re going to die. If you have a strangulated hernia or if you need a C-section, you aren’t going to make it.”

And anyway, Rick and Debbie assured themselves, he’d probably be fine. He would be working with the general population, and according to the World Health Organization, if your patients didn’t have significant fevers, they didn’t have Ebola. (“That turned out not to be true,” Rick said.)

He landed hours before Writebol left and got to work helping medical director Jerry Brown reopen the hospital. Scared of contamination, many staff stayed home. One night the entire hospital crew was Rick and one pharmacy tech.

Rick had been in Liberia for four weeks when his temperature began to rise. Right away, he isolated himself. When the tests came back positive for Ebola, he called Debbie.

“She was amazing during that time,” he told TGC. “She never once said, ‘What were you thinking?’ Never once. She was really incredible.”

Undeterred

But other people did. Decker remembers watching the news about Rick on a fitness center television. His workout buddy said, “That is the stupidest thing. I can’t believe he went there.”

He was not alone—comments sections and social media were full of people saying the same thing. The country was so thunderstruck by health care workers who would sacrifice themselves for Ebola patients that they were eventually named Time’s People of the Year.

Neither the criticism nor the praise ruffled Rick. He was flown in an isolation unit to Omaha, and at the end of the first week, was able to talk to Decker a little.

“He filled my ear—and I sat there taking notes—about all he saw in Liberia and what he felt needed to be done,” Decker said. “Here is this guy who just about died from one of the scariest diseases we can imagine, and his full attention is on a crisis in Liberia.”

On September 25, Rick left the hospital. Ten days later, he developed a fever and a cough, and had to return. His left eye fogged up. His muscles felt like sawdust. At first, he could only do three minutes on a stationary bike.

By Thanksgiving, he started to feel itchy for Liberia.

By January, he was back in Monrovia.

Gift of Generosity

“You have to realize it’s who God made them,” said Debbie of people who, like Rick, run toward fires and bullets and deadly contagious diseases when others are running the other way. “I remember realizing early in our marriage that his generosity—not just with money, but with all he is—is a spiritual gift. And I had to always remember that you can’t quench the Spirit, and the way the Spirit moves somebody to work out their spiritual gifts.”

Is it sometimes difficult for the spouse—and the parents and siblings and children and friends—who worry and wait?

“Yeah, I get frustrated with my doctor husband who is always willing to doctor anyone at any time,” she said. “But I have to let my heart be generous too, even if it’s not really my gift. I have to let God’s generosity pour out through him, and I grow in generosity by letting him exercise his spiritual gift.”

That’s “total surrender,” she told TGC. “It’s not putting conditions on how God leads.”

“The Sacras are not alone in their headlong abandonment of the rational rules of living which modern, well-educated Western professionals are meant to follow,” Fielder wrote.

He lists some: Jeff Perry, who stayed in rural South Sudan even after his retina detached, determined to work “with or without vision in my right eye.” Stephen Foster, who kept serving in Angola despite cobras, armed soldiers attempting to kidnap his nurses, and his son’s polio. Russ White, who nearly died of septic shock and then nearly died of a brain infection—but you’ll find him still working in Kenya.

“A crazy thing happens [to missionaries] where you no longer feel like you’re in a foreign land with anonymous people,” Decker said. “It becomes home. They’re our people, our family.”

In many ways, it’s a family unit even stronger than one that shares a last name. These are spiritual siblings united by their mission to save lives, both physically and also spiritually.

As a Christian, Rick “goes the extra mile at times, just to help someone in need of his attention,” said Rachelle Harris, a Liberian nurse who runs the HIV/AIDS program at ELWA. “Many of the HIV-positive patients found hope after an encounter with Dr. Rick, who told them, despite their situation, they can still live and become what they want to be. Sometimes he even cries along with them . . . his impact has brought hope to the lost and weary.”

“I love Liberian culture—I’m really immersed in it and I understand it,” said Rick, who can switch to a Liberian dialect so completely you think for a second he handed the phone to someone else. “I love teaching. I love making a difference in people’s lives.”

He’s not nearly done. With the $500,000 Gerson L’Chaim Prize, he’s planning to train students in family medicine—Liberia still only has one doctor for every 15,000 people. He’s going to install solar capacity so the hospital can have a more affordable source of electricity. And he’s going to create an intensive care unit—crucial in a country that has few resources to treat trauma victims, pregnant women with very high blood pressure, or sick newborns.

“The Sacras’ commitment represents the best of the missionary enterprise—to be committed to one people, a place, an institution, with radical love and sacrifice,” Fielder said. “When I hear stories like these I am always reminded of the first chapter of Ruth, when Ruth tells Naomi: ‘Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the LORD deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.’”

Among Rick’s friends and family, “I can’t think of a single person who said, ‘Don’t go back,’” Debbie told TGC.

“I’m proud of him for doing it,” Decker said. “We rest on the sovereign goodness of God. We walk in with our eyes wide open. There was no guarantee he was going to survive—same with Kent and Nancy—but we all would have said this is a thing worth laying down your life for.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.