Editors’ note: Come celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation with us at our 2017 National Conference, April 3 to 5 in Indianapolis. The conference theme is “No Other Gospel: Reformation 500 and Beyond.” Space is filling up fast, so register now. Prices increase after Reformation Day (October 31).

When John Calvin became pastor in Geneva, most Protestant churches didn’t have deacons responsible for caring for the poor. In the medieval church, the diaconate had become an office with largely liturgical responsibilities. Most Reformed churches, following Ulrich Zwingli and Heinrich Bullinger, assumed it was the state’s responsibility—not the church’s—to care for the poor.

Calvin decisively rejected all of these views. Identifying the church as Christ’s spiritual kingdom, Calvin insisted the church must witness to the justice and righteousness of Christ’s kingdom in its own way, in accordance with Christ’s commands. This meant, as one of the church’s essential ministries, it had to call men and women to serve in the spiritual office of deacon.

Justice, Not Charity

Calvin, like other Christians before him, believed God has given the earth and its resources to human beings. As those made in the image of God, we’re called to share our resources and serve one another. Calvin often used the language of rights to describe this principle. A person is defrauded, he argued, when a need is left unmet by someone with the power to meet it.

Caring for the poor, then, isn’t a requirement of charity but of justice, a basic demand of natural law. God is the “protector and patron of the poor,” Calvin says, the one who hears their cries and “feels himself injured in their persons.” Therefore, he won’t let their afflictions remain unavenged.

Government

Calvin believed one of the main responsibilities of civil government is to ensure the poor receive their rights. As he puts it in his commentary on Psalm 72:

God takes a more special care of the poor than of others, since they are most exposed to injuries and violence. . . . David, therefore, particularly mentions that the king will be the defender of those who can only be safe under the protection of the magistrate.

For that reason, a “just and well-regulated government will be distinguished for maintaining the rights of the poor and afflicted.”

The rich rarely need the government’s protection, yet the poor almost always do. Thus, Calvin preached, it is “praiseworthy for a good prince to relieve his subjects’ poverty.” He must do so not only by prohibiting practices such as unjust usury, but also by opening poorhouses, hospitals, and schools. Calvin believed all pastors should preach this command, for he saw it as the clear teaching of God’s Word.

Yet Calvin was no utopian. Just as humans fail to care for the poor, so government does little better. This is why it’s so vital for the poor to look to Christ as their true King who secures mercy and justice for them. It is ultimately to Christ that passages like Psalm 72 point, and only in the kingdom of Christ is true justice fully secured. Thus the gospel comes to the poor as especially good news.

Church

For Calvin, this is where the role of the church comes in. He viewed the church as the primary expression of Christ’s kingdom in this age. It is the arena in which Christ’s Word and Spirit are at work, regenerating men and women and knitting them together in solidarity. For that reason, the church must be the place where the poor find justice: “Except then we endeavor to relieve the necessities of our brethren and to offer them assistance, there will not be in us but one part of true conversion.”

The Spirit establishes the righteousness of God’s kingdom by securing a kind of communion among believers that extends “to mutual society and fellowship, to alms, and to other duties of brotherly fellowship.” Indeed, Calvin describes this as one of the “marks whereby the true and natural face of the church may be judged.”

Diaconate

The question at this point is a simple one: “How?” This can’t simply be left to informal actions of individuals. On the contrary, in fact, as we learn from Acts 6 that the Spirit’s work is to be institutionalized in the church through the diaconate. Calvin affirmed the old Christian saying that the property of the church is the property of the poor. He followed the medieval church’s rule of thumb by recommending churches devote at least half of their resources to caring for the needy.

To be sure, the diaconate looked different in Calvin’s Geneva than it does in most Reformed churches today. Deacons were appointed by the government in consultation with pastors, and they cared for the poor through a government-funded institution: the general hospital. Various kinds of deacons worked through the hospital to collect and dispense resources for the poor; care for the sick and disabled; secure shelter and food for the homeless, widows, and orphans; and find jobs or job training for the unemployed. In all this, they worked closely with the pastors and the city government.

Calvin also established a second diaconal system in Geneva—the Bourse Française—which looked more like the system in later Reformed churches. He established the Bourse to care for the increasing numbers of mostly French refugees pouring into Geneva to escape religious persecution. As a purely ecclesial affair, it neither received funding from nor was overseen by the government.

Throughout his ministry Calvin stressed that the church must embrace its call to care for the distressed. He viewed this not merely as an obligation of charity, but as a demand of justice. The diaconate isn’t “a profane or mundane office, but a spiritual charge.” If Christ is “to rule and have order in the church,” then “the poor must be cared for. And for that, we need deacons.” Indeed, without such an office it’s “certain we cannot brag that we have a church well-ordered and after the doctrine of the gospel.”

Our Witness Today

Times have changed, of course. Diaconal models in 16th-century Geneva won’t work in 21st-century America. Our economic, social, and political conditions forbid it. These days, talk of “justice” in the church is often either politicized according to a Right or Left agenda or, reacting to such politicization, silenced altogether.

But by highlighting the true nature of Christ’s kingdom and the role of righteousness in the church’s mission, Calvin’s theology might help us avoid these extremes. He was careful to specify that the church shouldn’t tell the state how to govern. Deacons weren’t involved in policy activism, though sometimes pastors did advise or critique the Genevan government.

Calvin helps us see that while the church must spurn worldly political agendas, it must nonetheless reflect the righteousness of Christ’s kingdom in accord with its gifts, opportunities, and circumstances. This will look different for each church, since both needs and giftings vary according to context.

Yet it remains clear that our churches may not ignore this task. We may not ignore the cries for justice from our brothers, sisters, and neighbors. Far too often we’ve reduced the diaconate to an administrative office that occasionally dispenses financial aid. Christ calls deacons to do more.

If we fail at this, even if we do many other things well, Calvin would say we don’t have a church ordered according to the teaching of the gospel.

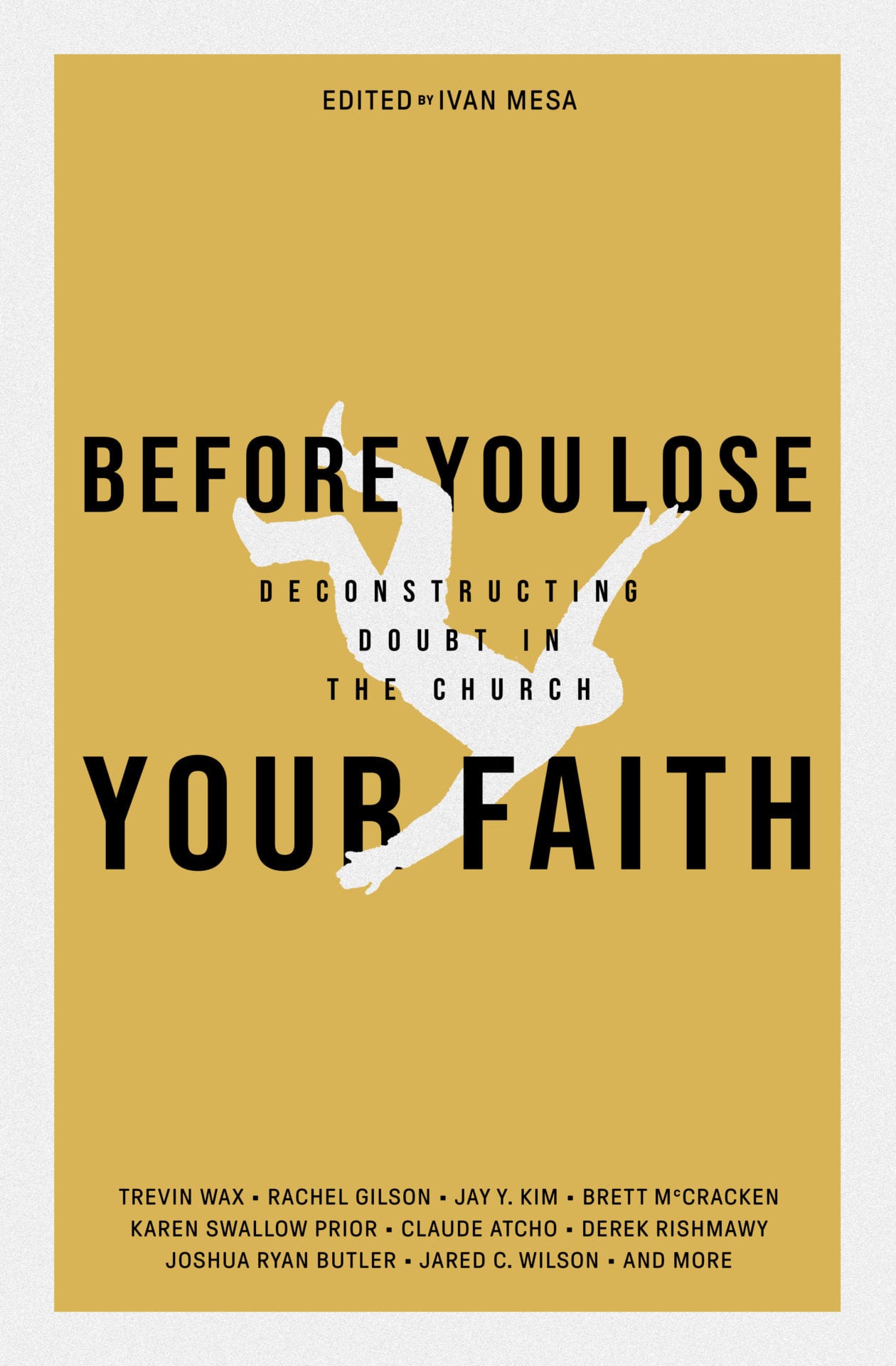

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!