The following article is an adapted excerpt from the new book Coming Home: Essays on the New Heaven & New Earth, edited by Don Carson and Jeff Robinson.

The Old Testament purposefully has an unresolved narrative tension in it, and this very tension is the whole basis of the gospel. Narrative tension means you don’t know what’s going to happen and there are opposing forces at work. In other words, “Little Red Riding Hood took her grandmother some goodies” is not narrative. It’s just a report. “Little Red Riding Hood took her grandmother some goodies, but the Big Bad Wolf was waiting to eat her up” is a narrative, because we’ve got tension. We’re led to ask, “What’s going to happen?”

The narrative tension that drives the whole book of Deuteronomy is the same narrative tension that drives the whole narrative arc of the Bible, all the way up to the cross.

“But,” you reply, “I guess it doesn’t get resolved in Deuteronomy.” Yes and no. What is beautiful about the Bible is the wonderful foreshadowing we see throughout of how resolution is going to happen. And there is foreshadowing in Deuteronomy 30.

This chapter says much about the future, and although in one place it looks like Moses is speaking about the present, Paul explains in Romans 10 that Moses was talking about the future.

Moses says three things about the future in this chapter.

1. ‘You cannot be good.’

The first thing he says is we will all fail to live as we ought. This is one of the most important things about Deuteronomy 30. In fact, if you don’t keep this in mind, you’ll misread the last part of the chapter. Look at verse 1:

When all these blessings and curses I have set before you come on you and you take them to heart wherever the LORD your God disperses you among the nations . . .

Moses says the Israelites will be dispersed. If you go back to Deuteronomy 28, the ultimate curse is exile and dispersion. So verse 1 is essentially saying, “You will fail. You will bring all the curses of the covenant down on you. The worst that God says will happen if you disobey the covenant will, in fact, happen.”

American readers of Deuteronomy know how our culture loves motivational speakers. We enjoy having others tell us what we can do and how we can live. In some ways, the whole book of Deuteronomy is like a motivational speech. It’s a wonderful ethical treatise. It’s a vision for integrity, justice, and human life at the highest. Moses is preaching the first sermon series in history, as some have described Deuteronomy, and he’s basically saying, “I want you to live like this”—much as a motivational speaker would today.

But how does Moses’s motivational speech end? After he tells the Israelites to live according to the ethical standards of chapters 1 to 29, he effectively concludes, “Let me point this out. You’re going to fail! You’re not going to do any of this stuff I’m talking about! You’re going to fail miserably! I am wasting my breath!”

You might say that’s not good motivational speaking, and you’d be right. But it’s great gospel preaching.

You might say that’s not good motivational speaking, and you’d be right. But it’s great gospel preaching.

Just as Moses begins by telling the Israelites, “You’re going to fail,” gospel preachers have to constantly remind people what they already know in their hearts but won’t admit: “You know what to do, but you will never do it unless you get some kind of outside help. You will never pull yourself together.”

2. ‘God can fix your heart.’

Deuteronomy also says God has a plan to fix hearts, to pull us together. In Deuteronomy 30:2–5, Moses predicts the Israelites will be exiled and God will bring them back. But when he gets to verse 6, he says:

The LORD your God will circumcise your hearts and the hearts of your descendents, so that you may love him with all your heart and with all your soul, and live.

He’s talking about something the rest of the Bible brings out. Jeremiah and Ezekiel call it the new covenant. Paul in Romans 2:29 says that our hearts are circumcised, and in Philippians 3:3 that we are the true circumcision. So this is the gospel, and this is looking far beyond the lives of the Israelites at that time.

What does it mean to have a “circumcised” heart? It sounds like a scary idea, doesn’t it? Peter Craigie says when Deuteronomy speaks of God circumcising the heart, it’s a metaphor for God doing surgery on your heart. Whereas circumcision was a sign of external obedience, entry into the covenant community, and submission to the law of God, heart circumcision is the motivation of inner love to obey. The text says, “The LORD your God will circumcise your hearts and the hearts of your descendants, so that you may love him with all your heart and with all your soul, and live” (Deut. 30:6).

Think about marriage. Over the years, there have been many arranged marriages where the proverbial knot was tied, but there was no love. But when I was falling in love with my wife, and she asked me to make a change in my life, Kathy’s wish was my command. I was in love, so I didn’t think of it as obeying her or submitting to her will, though in a sense I was. She wasn’t demanding anything, but out of love I was changing that thing in my life. What you ought to do and what you want to do become the same thing. Our pleasure and our duty are the same. That’s a circumcised heart.

Our pleasure and our duty are the same. That’s a circumcised heart.

There’s a strange phrase in Colossians 2:11 that could be translated, “In Christ, you [Christians] have been circumcised in the circumcision of Christ.” Paul is teaching that you receive not only a new heart when you become a Christian, but a circumcised heart because of the circumcision of Christ.

And what is the circumcision of Christ? On the cross, Jesus was experiencing the curse of the covenant: to be cut off. If you lie, cheat, or wrong someone else, being cut off from the congregation is the penalty Deuteronomy gives again and again. But the penalty for disobeying God is to be cut off from him. And to be cut off from him is to be cut off from life, light, and every good thing. On the cross, Jesus endured that penalty. He was suffering the cosmic experience we deserve, the punishment for our sin.

Think back to Eden. Adam and Eve were forced out—or cut off—because of their sin, and an angel with a sword was stationed to block the way to the tree of life. The only way back to the tree of life was to go under the sword. And on the cross, Jesus Christ went under the sword. In that sense, he was circumcised.

Because Jesus Christ experienced that circumcision for you and me, not only objectively do we gain a relationship with him through faith, but subjectively that image of him bearing our curse makes our pleasure the same as our duty.

If seeing what Jesus did at Calvary—taking your cosmic “cutting off” for you—moves you to say, “I do deserve to be cut off, and Jesus did that for me,” then you know you’re experiencing circumcision of the heart.

3. ‘Jesus has done it for you.’

The final thing Deuteronomy 30 says about the future comes at the end of the passage, where it seems to speak only about the present. So far, Deuteronomy 30:1–6 has been looking down the corridors of time, saying in effect, “First, you’re going to fail, all the curses are going to come upon you, and you will go into exile; but God will bring you back and circumcise your heart.” That’s the promise of the new covenant and the new birth. But then in Deuteronomy 30:11–15, Moses tells them, “See, I set before you today life and prosperity, death and destruction.”

It may seem like Moses is returning to the present when he describes what he’s demanding of the Israelites “today.” He says his law isn’t too difficult but is near—even in their mouth and heart. What does that mean? On the one hand, it means the Israelites have no excuse. The law of God is clear. They don’t have to go over the sea to talk to sages or to mystics to figure out God’s will; instead, it’s come to them.

And yet, as Tom Schreiner points out, Paul would later quote this passage knowing Moses had already said the Israelites cannot and will not keep this covenant. Therefore, Paul is absolutely right in how he interprets Moses in Romans 10:4, 6–9. Schreiner says Paul is applying Moses’s words to show that, in the end, the only word that won’t crush you—that’s not too difficult for you, that you don’t have to cross the sea to get—is the gospel.

Jesus has already done the impossible for you.

If you try to save yourself, it’s like telling Jesus that what he did doesn’t matter.

Don’t try to earn your salvation, Paul says. To do that is to bring Jesus up from the abyss or keep him back in heaven. But he came from heaven and went into the abyss to save you. If you try to save yourself, it’s like telling Jesus that what he did doesn’t matter.

Only the gospel is the word that is not too difficult for you, and only the gospel will not crush you. Any other word will. Therefore, Moses is basically saying, “Someday the gospel will go forth.”

And by God’s grace, it has.

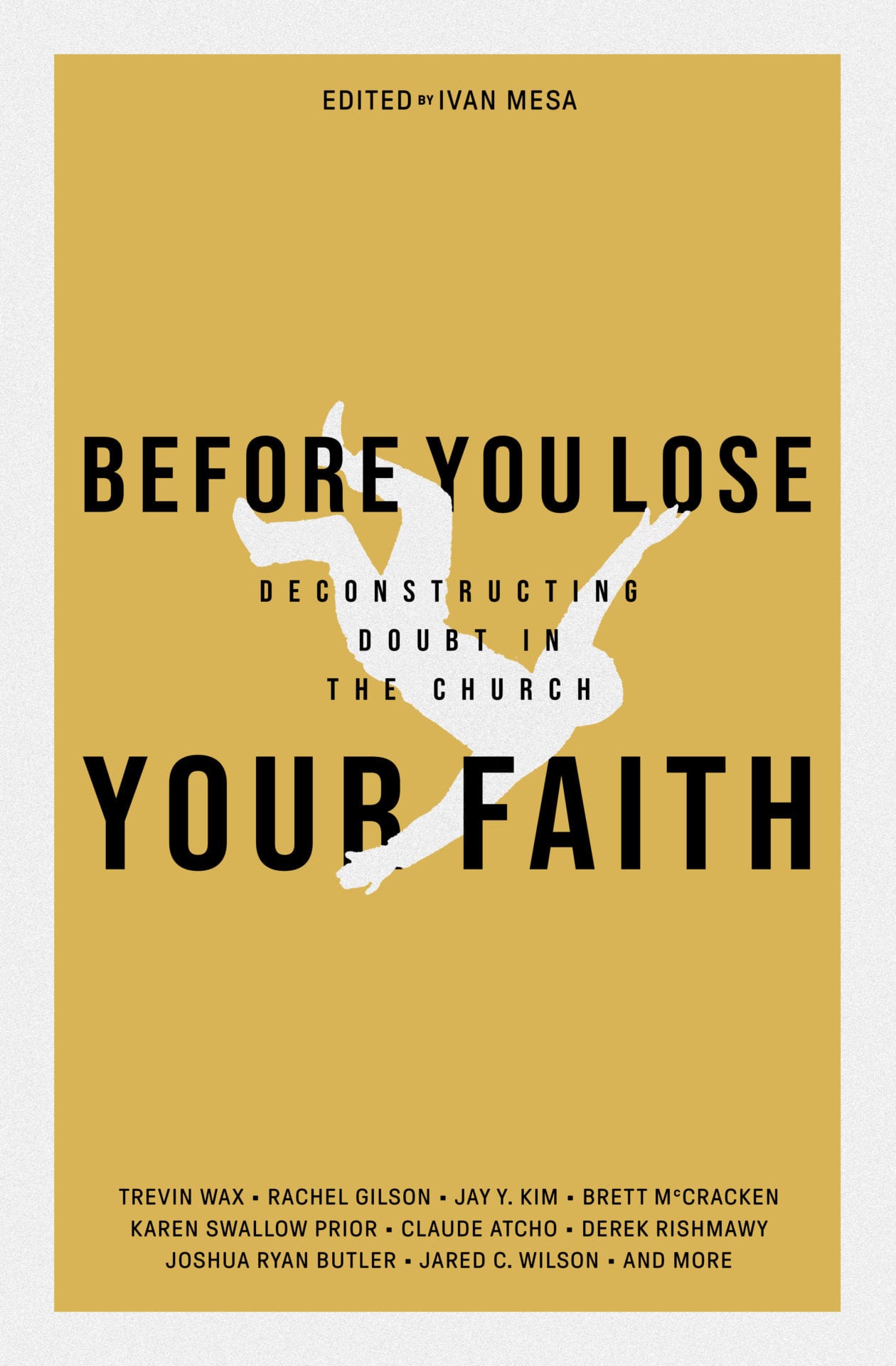

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!