The pro-life movement has always been animated by compassion and a zeal for human rights. But if you asked people on the streets whether they associate those two things with the pro-life movement, I wonder how many would agree.

It’s not that the average grassroots pro-lifer has changed—at the March for Life in D.C., in conversations with staunch advocates, or during visits with workers at pregnancy resource centers, I see the same love, passion, and earnest care for the unborn (and, importantly, for their mothers).

But recently, our “pro-life” political representatives around the country have been less than inspiring. Donald Trump has bragged about sexually assaulting women (though he has denied actually assaulting women). Tim Murphy, a “pro-life” congressman, urged his mistress to get an abortion when she said she might be pregnant. Roy Moore, a Republican politician running for U.S. Senate from Alabama, was accused of sexual harassment and molestation of minors by several different women prior to his electoral race (which he lost a month ago).

Many pro-choice advocates, observing this pattern, have claimed the moral high ground in the abortion debate. While our conversations about abortion should consider the humanity and rights of the unborn child, pro-choice advocates have instead turned the conversation entirely to the question of women’s choice and rights—even staging Handmaid’s Tale-inspired protests to reinforce their argument. They point to Trump, Murphy, and Moore, and then tell America, “See? These men have never really cared about the unborn. They care about taking away a woman’s voice and choice.”

I’ve feared that, if these tendencies persist, many Americans—especially swing voters and young people—could turn away from the pro-life cause. But perhaps there is a way we can prevent that.

Learning from Abolitionists

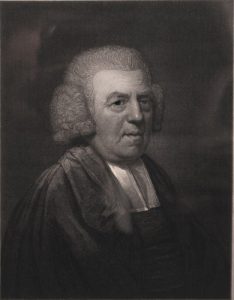

Many pro-lifers have compared themselves to 19th-century abolitionists. To them, both issues hinge on human dignity and the right to life, liberty, and human flourishing. Both have been unpopular and controversial movements, deeply inspired by moral arguments and financial concerns. But to garner inspiration for their cause, there’s perhaps no better example for pro-lifers than William Wilberforce and the English abolitionists of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One useful volume on this subject is Eric Metaxas’s bestselling biography, Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the Heroic Campaign to End Slavery.

In England during Wilberforce’s life, slavery was an accepted practice; while many believed it was wrong, most were willing to turn a blind eye to the trade or declare it a “necessary evil” for the commonwealth. Few questioned it with the vehemence or passion of Wilberforce and his compatriots.

How, then, were Wilberforce and the abolitionists able to ban slave trafficking—and eventually, slavery itself—in their lifetimes? What massive concentration of resolve managed to turn a whole empire against slavery? After all, slave traders were wealthy and influential members of society; many members of Parliament had an interest in keeping the trade alive. The industrial complex built on the loathsome practice was large and influential, and its adherents protested Wilberforce’s efforts vehemently.

Wilberforce and his allies didn’t content themselves with advancing a political agenda. They focused on the cultural, social, and ideological mores that allowed slavery to exist in the first place.

It’s important to note that, faced with the passivity or antagonism of the powerful and influential, Wilberforce and his allies didn’t content themselves with advancing a political agenda. They focused on the cultural, social, and ideological mores that allowed slavery to exist in the first place—indeed, the abolitionists turned themselves passionately and primarily to public awareness, cultural causes, and grassroots campaigns.

Before Wilberforce ever petitioned Parliament for the abolition of the slave trade, his compatriots had begun working on the hearts and minds of the British people. They knew this was where the battle must begin.

Changing Hearts and Minds

During this time, William Clarkson wrote about slavery as an investigative journalist. He exposed the horrors of the Middle Passage fact by fact, detailing restraint and torture, abuse and cruelty. He documented the mortality rate of both sailors and slaves aboard ships. He recounted the firsthand accounts of slaves, sailors, and captains who witnessed the system’s hideousness. John Newton, slave-ship-captain-turned-Anglican-clergyman and writer of the famous hymn “Amazing Grace,” wrote a pamphlet on the slave trade and his own work “in a business at which my heart now shudders.”

The abolitionists used art and music powerfully—Josiah Wedgewood’s antislavery cameo (“Am I not a man and a brother?”) was turned into brooches and pins. Posters of the horrifically inhumane “storage” system employed aboard slave ships were posted around England. William Cowper and Samuel Taylor Coleridge both wrote antislavery poems for the cause, and Cowper’s was set to music. Famous playwrights like Hannah More joined the abolitionist fight and built up popular support. A boycott of West Indian sugar targeted the slave traders’ coffers.

The work was neither easy nor swift. For 20 years, Wilberforce petitioned Parliament to abolish the slave trade. It took 20 years for that bill to pass, and then another 26 years to abolish slavery as a whole.

All this was happening even as Wilberforce and his allies failed (time and time again) to abolish the slave trade in Parliament. As they worked to turn public and cultural support in their favor, they slowly sought to move the political ball forward—one year, and one bill, at a time. But the work was neither easy nor swift. For 20 years, Wilberforce petitioned Parliament to abolish the slave trade. It took 20 years for that bill to pass, and then another 26 years to abolish slavery as a whole. Nonetheless, those 46 years changed the entire character and moral compass of the nation. The abolitionists’ accomplishment was monumental.

Character and Consistency

There are several personal traits that likely helped Wilberforce and his political allies. First, they were highly virtuous and compassionate people. Wilberforce paired this integrity with a winsome and charismatic manner. In a world that disdained the goody-two-shoes sincerity of dedicated Christians, Wilberforce’s cheer and charisma drew people to his cause and his faith.

To read about the Clapham Sect (the community of Christians and abolitionists to which Wilberforce belonged) is to uncover a committed group of culture transformers: Christians who took the implications of their faith seriously on both a private and public level.

What would happen if the pro-life cause raised up leaders like that?

National Qualms about Abortion

With excellent leaders, the pro-life movement would be able to organize those with concerns about abortion across the political spectrum. Pew Research Center has found that about 3 in 10 Democrats believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. A Fox News poll in 2016 put that number at 27 percent. Neither African Americans nor Latinos (both core Democratic constituencies) are unequivocally pro-choice: 35 percent of blacks and 49 percent of Latinos believe “abortion should be mostly illegal.” At least 60 percent of Americans believe abortion should be outlawed after 20 weeks.

These numbers by no means indicate that a majority of Americans want to outlaw abortion entirely. But they do demonstrate that many have qualms regarding the practice. A 2010 Pew Forum poll found that about 50 percent of women believe abortion is morally wrong, while 12 percent “consider it hazy depending on circumstances.”

The pro-life cause has a lot of work to do in the cultural and grassroots realm.

Yet despite these public hesitancies (as well as Republican control of the White House and Congress), Congress was unable to defund Planned Parenthood last year, a step far from outlawing abortion. This defeat suggests that the pro-life movement may not have the leaders it needs; it also suggests that the pro-life cause has a lot of work to do in the cultural and grassroots realm.

The Pro-Life Movement We Need

Changing public opinion means raising awareness. It means pro-lifers need to be good storytellers. LiveAction and the Center for Medical Progress have targeted Planned Parenthood with investigative stories and sought to address many of its illegal or questionable activities. But there are few other organizations regularly telling stories or creating media that pinpoint problems with abortion. When the Kermit Gosnell story broke a few years ago, many in the mainstream media ignored it until whistleblowers forced them to pay attention.

Pro-lifers also need to be thoughtful artists. Poetry isn’t as popular as it was in Wilberforce’s day; we don’t wear brooches anymore. But musical artists have enormous clout, as do athletes and actors. Nowadays, we have bloggers and Instagram and YouTube stars. Our platform potential is expanding, not shrinking, with time. And the art we have seen on this issue—such as the award-winning film Bella, which came out in 2006—has had a positive effect on the pro-life cause. We just need more of it.

Finally, pro-lifers need to be compassionate advocates. Almost half of the women who procure abortions are living under the federal poverty line—and many cite financial scarcity as their primary reason for getting an abortion. Understanding this strain, and helping address it, should be an integral part of the pro-life cause—not just on a political level, but on a cultural and grassroots level. It should be a natural extension of the pro-life cause, which is determined to fight for the most vulnerable among us. Wilberforce didn’t fight poverty and animal abuse so that his anti-slavery crusade would be “cooler” or more appealing. He was determined to fight oppression, injustice, and suffering in all its forms.

Pro-lifers need to be good storytellers . . . thoughtful artists . . . [and] compassionate advocates.

Many of those who voted for Roy Moore in November’s election told me that voting pro-life, like voting anti-slavery, couldn’t wait. They were determined to move the political battle forward, no matter how weak or problematic the vessel.

But as I considered the country we’re living in, and the culture we’re surrounded by—with its #ShoutYourAbortion campaigns and Planned Parenthood celebrity rallies—I was left with this thought: If we’re going to compare the pro-life movement to the abolitionist cause, we’re going to need leaders like Wilberforce—leaders whose integrity extends beyond shallow posturing into every facet of their lives. We are going to need more than partisan politicians—we’re going to need tender culture warriors and humanitarians, winsome orators and artists. Because pro-lifers won’t be able to win votes unless and until they win over hearts and minds—until they, too, demonstrate themselves to be the conscience of the nation.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.