David Dockery, president of Trinity International University, knows the feeling of exhaustion. His wife, Lanese, gave birth to their three boys in three years. While he was president at Union University, one student shot another, and an EF4 tornado tore through while half of the students were on campus.

But the most emotionally exhausting day in his life came on January 24, 1992.

“It was one of the happiest days and one of the saddest days of our lives jammed together,” he said.

For Dockery, January 24 started early. His commute to downtown Nashville normally took about 20 minutes. Although he was an assistant professor at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (SBTS) in Louisville, he was on loan to the Southern Baptist Sunday School Board (precursor to LifeWay Christian Resources) in order to serve as the general editor for the New American Commentary series.

But that Friday the drive was three hours, and took him up Interstate 65 back home to the SBTS campus in Louisville.

That he was employed at the seminary at all was a minor miracle, the result of a growing conservative resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), which included pressure to hire faculty who affirmed biblical inerrancy at SBC institutions.

January 24 would mark a sharp turning point, both in his life and also in the theological direction of the SBC’s oldest seminary.

Dawn of the Conservative Resurgence

After World War II, the SBC shifted from a theological focus to a programmatic focus, Dockery wrote. Southern Baptists filled their Sunday schools in the 1950s, but many leaders drifted away from biblical orthodoxy.

As in many other post-war denominations, SBC seminary faculty in the 1960s attempted to fit the Bible and science together in a way that meant “personal religion can be held by intelligent people,” according to progressive pastor Cecil Sherman. Intelligent people believed science, which appeared to be on Darwin’s side, so biblical accounts that seemed too hard to believe—a six-day creation, a worldwide flood, a fish swallowing a man, or a virgin giving birth—ended up on the chopping block, SBTS dean Gregory Wills wrote in 2010.

The progressive trend continued into the ’70s and ’80s, when “SBTS wanted very badly to be seen as a peer to the divinity schools at Duke, Yale, and Princeton,” Dockery said. “Academically, Southern was always out in front among the SBC seminaries. But in terms of relating to the people in the pew, the seminary was often out of touch.”

Appalled by theological confusion across the SBC, Southern Baptists in the pulpits and pews began to pressure the seminaries, eventually compelling the presidents to promise to hire staff who believed in the inerrancy of the Bible.

“SBTS faculty started doing research to see if they could find a conservative Southern Baptist who understood Baptist life, who affirmed biblical inerrancy, and who would work constructively with them as a faculty member,” Dockery said. They found one teaching at a small college in Dallas and serving as the editor of its theological journal.

“I went as the county fair blue-ribbon conservative, and taught New Testament and theology,” he said with a grin.

Dockery remembers sitting with the faculty during convocation at the start of his second year.

“[President Roy Honeycutt’s] address was on Galatians 4, on the story of Sarah and Hagar and the importance of Christian freedom,” Dockery recalled. “Then he said, ‘The Hagarites, they’re bound to the law—you know, people like these inerrantists who can’t understand the freedom of the Word of God.’

“Every faculty member turned and looked at me. Every one of them,” he said. “I thought, I am an alien in a foreign land.”

(Later, a colleague broke the tension with a sign on his door: “Hagarites live here.”)

Dockery taught at the school for two years before taking a leave of absence to work on the conservative New American Commentary in Nashville. While he was there, a dean position at SBTS opened up.

The job was an influential one—hiring faculty, deciding on academic programs, and helping shape the vision for the school. Under pressure from the board to find a conservative, the administration chose Dockery.

But the faculty—almost entirely made up of moderates or progressives—were scheduled to vote on January 24, and no one was sure what they’d do.

Afternoon Vote

After lunch on January 24, wearing his standard-fare dark suit, Dockery stood before about 70 faculty members, microphone in hand, and answered questions.

They asked him about theology and church polity. They asked about his leadership style and understanding of shared governance. They asked about accreditation issues. They asked how he would represent the faculty to the administrators, how he would represent the faculty to the board, how he would represent the seminary externally.

It lasted two and a half hours.

“I was prepared for that,” Dockery said. “The Lord was with me that day.”

Afterward, Dockery was stashed in a nearby office while the faculty took just 20 minutes to approve him with a 95 percent majority.

“It was the biggest day of my life professionally at that point,” Dockery said. Elated, he called his wife to let her know he was on his way. All was well; she couldn’t wait to see him.

He set off on the three-hour drive home.

Worst News

When Dockery walked into his rented home in northern Nashville, he immediately knew something was wrong. His three active boys, ages 10, 11, and 12, were in the living room with his wife, Lanese. Everyone was crying.

“They had just received a phone call from Birmingham,” Dockery said. Both he and Lanese had grown up there, in the middle of race riots and Bull Connor and Martin Luther King Jr.’s jailhouse stay.

“PawPaw’s been shot,” the boys told him.

Lanese’s parents, William and Polly Huckeba, lived in the Bush Hills neighborhood of Birmingham, sticking around when their neighbors left in a flurry of white flight. While Dockery was on the road, Lanese’s father, a retired steel worker, had deposited his retirement check in the bank and stopped home to pick up his wife on the way to visit friends. As he stepped out of the car in his driveway, a man approached.

“He took the money, shot him multiple times in the chest, and ran,” Dockery said. Lanese’s mom saw the whole thing from her window.

Huckeba was declared dead at the hospital at 5:03 p.m.

His killer has never been caught.

Civil Rights

Dockery’s father-in-law was one of 148 people murdered in Birmingham in 1992, the deadliest year the city had seen since the early 1930s. It would prove to be the peak; homicides haven’t been that high since.

It was also a “hotbed of skinhead activity” that year, with at least one public demonstration by both white supremacist skinheads and Klansmen, according to The New York Times.

“My in-laws lived on the western side of Birmingham, which had been the most racially charged part of the racially charged history of Birmingham,” Dockery said.

When Dockery was 10 years old and sitting in his own Baptist church, white supremacists less than four miles away planted 15 sticks of dynamite under the steps of the African-American 16th Street Baptist Church.

“I came home, and four little girls the same age I was went to church and didn’t come home,” he said. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

It was the same year Martin Luther King Jr. led a nonviolent campaign of business boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins, and protest walks in the segregated city. Dockery remembers Bull Connor turning water hoses on protesters, King writing his “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

“I grew up in that world,” he said. “I don’t know why, perhaps because I believed the song I had been taught as a child that ‘Jesus loved the little children of the world, red, yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight,’ but I did see things differently from many others around me during those days.”

Dockery credits the grace of God and a mother who stressed the importance of showing God’s love to all people. Though he “didn’t have everything worked out in life,” he did know that he wanted to be “on the other side of racism.”

Dockery was in 7th grade when Brown v. Board of Education and Alabama’s school choice act finally took effect in his school through a handful of African-American students. “They were very brave,” he said.

More came each year, but not enough according to the courts. By his senior year of high school, a federal judge issued an order to speed things up in his western suburb of Fairfield. Instead of one black and one predominately white high school, one would now hold all freshmen and sophomores, the other juniors and seniors.

In response, the white freshmen and sophomores, who were supposed to head to the previously all-black building, “went to private school,” Dockery said. More of the white upperclassmen stayed, comfortable in their building and their recognized success in music, academics, and sports. Soon the city would change dramatically with white flight; today around 92 percent of the city is African American, with about one-quarter of the population living below the poverty line. (Watch how one church is bringing hope there.)

In that key transiton year, Dockery served as the vice president of the student body. The school year was “entirely disrupted” by the change, and “when we got to the end of that year, all but a handful of white students decided to boycott the graduation.”

He was one of the few who stayed. And since the student body president wasn’t there, that left Dockery with the graduation speech.

What he said was typical—“you know, thank the principal, thank the teachers, thank the parents, thank one another”—but the moment earned Dockery his photo on the front page of the Birmingham newspaper the next day. It was his first public effort toward racial reconciliation.

Civil Rights at Church

Dockery knew the judge who ordered his high school to speed up integration in 1969. Seven years earlier, H. H. Grooms had ordered the University of Alabama to accept three black students, prompting Governor George Wallace to block them in the doorway. (Dockery would enroll there in the fall of 1970, and as a student worker for the athletic department, would occasionally be asked to room with the black athletes on road trips when it was unpopular to do so.)

Grooms also attended Dockery’s church. Or rather, he used to.

The summer after graduation, Dockery’s Southern Baptist church of about 1,000 watched as an African-American woman named Winifred Bryant and her 11-year-old daughter, Twila, walked down the aisle and asked to join the congregation. Championed by pastor Herbert Gilmore, the move was a bold one, not only for a white church in Birmingham, but also for the SBC, which split from the northern Baptists in 1845 over the ability of slave-owners to become missionaries. (The SBC was in favor; the northern Baptists weren’t.)

The debate over Bryant—and Gilmore—raged hot all summer, including an attempt to declare the pulpit vacant while Gilmore was at a Baptist World Alliance meeting, rumors that Gilmore was a communist, and a 2:30 a.m. vote that kept Gilmore in his job by just four votes.

Finally, on a Sunday morning in September, the congregation voted 240 to 217 to keep the church all white; it immediately split when about 250 members walked out. (Gilmore was one. Grooms, an outspoken supporter of Gilmore, was likely another.)

But even then, the issue wasn’t simple. Political, racial, and theological issues all swirled together in ways that continue to befuddle the denomination today.

Theological Liberalism

At the same time First Baptist was wrestling with whether to admit black members, they were also wrestling with the theological liberalism in the SBC.

“The church was severely divided about Dr. Gilmore before the black persons ever came forward for membership,” First Baptist stated in 1971, about four months after the split. “The division involved his . . . liberal and humanistic preaching which de-emphasized the Bible and his failure to promote evangelism,” among other things.

Some, including Dockery’s parents, charged Gilmore with not believing in the biblical accounts of creation or the flood, the virgin birth of Christ, or the infallibility of the Bible.

If true, he probably learned those views in seminary—Gilmore was a graduate of SBTS in the 1960s.

From Progressive to Conservative

Just a year after Dockery’s appointment to dean in 1992, SBTS president Honeycutt stepped down. Some of the faculty immediately offered up Dockery as a replacement.

But Dockery knew that if he lost, he’d have to leave the seminary, and he loved his job. So instead he promised to “cheer and help make this thing work for whoever is elected.”

He then recommended Albert Mohler, who still leads SBTS and is credited with turning it in a conservative direction. Mohler and Dockery set to work immediately, hiring five conservative faculty members before Dockery took over the presidency at Union University in 1996.

The pressure to turn the seminaries was “Baptist congregationalism at its best,” Dockery said. “Now SBTS is made up of people who are committed to the truthfulness of God’s Word.”

The SBC and its seminaries are also making slow, halting progress toward racial reconciliation. One of the first to champion the denomination’s first black president—Fred Luter, who was elected in 2012—was Dockery.

Back to Birmingham

On January 24, Dockery sat with his family in the living room as they cried over PawPaw’s death and prayed together. Then they got moving. Less than two hours later, they were packed and in the car, heading south on Dockery’s third three-hour drive of the day.

They pulled into Birmingham around midnight, finally putting an end to one of the worst and best days of Dockery’s life.

He spoke at the graveside service a few days later, then dedicated his book Seeking the Kingdom to Huckeba.

The tragic events of his family’s life in Birmingham helped Dockery see the urgent need for progress in race relations. After becoming dean, Dockery named the first two African-American faculty members in the School of Theology at SBTS. And during his two decades of presidency at Union, he hired more minority faculty, established a center for racial reconciliation, and saw the minority student enrollment rise from 9 percent to 20 percent.

Dockery was the first white person to give the keynote address at the annual West Tennessee NAACP meeting (where he received their racial reconciliation award); chaired an SBC summit on how seminaries can equip non-Anglo students; and is now working with faculty and staff to call Trinity to a renewed commitment to racial reconciliation.

“My life at almost every chapter has played out attempts to be an agent of reconciliation,” Dockery told SBC Life in 2013. Two books—his co-authored Building Bridges and essays gathered to honor him in Convictional Civility—underline that theme.

“By God’s providence, I was in the right place at the right time for a lot of things,” he said. “God put me in the right place. That’s the only way I can understand it.”

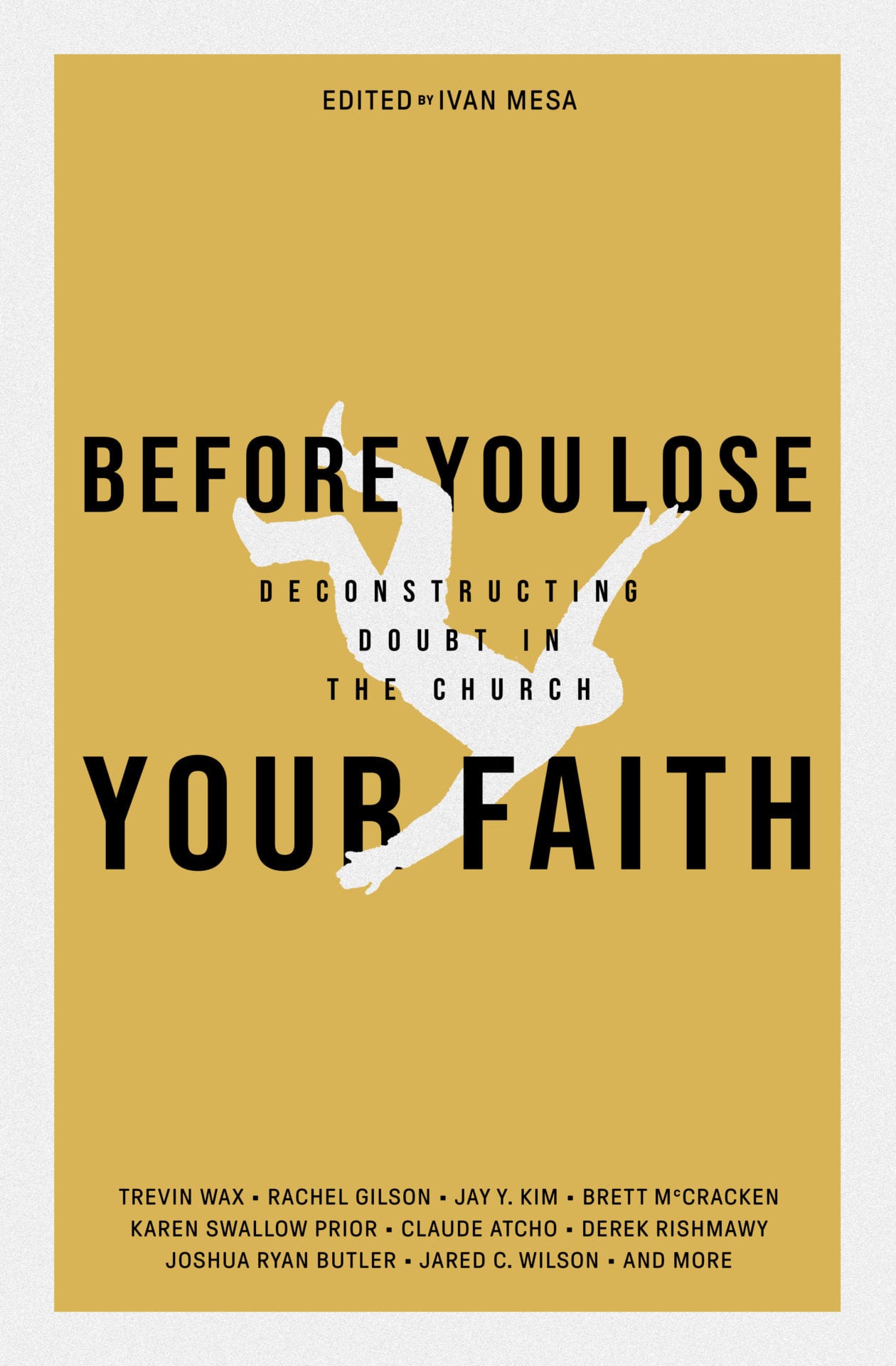

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!