Earlier this year Christian colleges in California got a scare when a lawmaker introduced SB 1146, a proposal to deny state funding for schools that enforce religious beliefs around sexuality and gender, such as organizing bathrooms by biological gender or limiting married housing to those in a traditional marriage.

After outcry from religious leaders—including the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission’s (ERLC) Russell Moore, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s Albert Mohler, and Trinity International University’s David Dockery—the bill was amended. The schools—including Biola University, California Baptist University, and Azusa Pacific University—now must disclose any exemption to anti-discrimination laws and report any expulsions on moral grounds to the state, but they won’t lose state funding.

While some are hopeful that the incoming Republican White House and Congress will safeguard religious liberties, others worry that the federal victories won’t protect religious organizations from state restrictions. California, for example, could simply re-consider the same bill in 2017.

In fact, 110 of the 137 candidates endorsed by Equality California (the organization that sponsored SB 1146) won at the federal, state, and local level. In North Carolina, the next governor will likely be Roy Cooper, who was endorsed by the pro-LGBT Human Rights Campaign (HRC). Oregon’s governor-elect, Kate Brown, was also endorsed by HRC.

The 70 policy changes that HRC recommended at a federal level will likely be retooled for use in state legislatures, said Shapri LoMaglio, vice president for government and external relations at the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU).

And as the pro-life movement can attest, focusing on state legislation can be effective even without federal support. In the last five years, states passed more than 300 abortion restrictions, more than 150 abortion providers shut down, and America’s abortion rate dropped to its lowest since Roe v. Wade in 1973.

“In states like California where the legislature isn’t as sympathetic to religious liberty, we can expect to see efforts [to pursue expanded sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) rights at the expense of religious institutions],” LoMaglio said.

Equality California lamented that SB 1146 didn’t go far enough, and promised economic and political backlash against those who claim a “‘right to discriminate’ based on their personal religious beliefs.”

Concerns like this prompted the CCCU, in conjunction with the National Association of Evangelicals, to convene meetings with more than 200 faith leaders in nine cities across the country this year.

The solution the CCCU is proposing: Fairness for All, federal legislation that would protect religious liberties for institutions while at the same time offering certain civil rights to LGBT people.

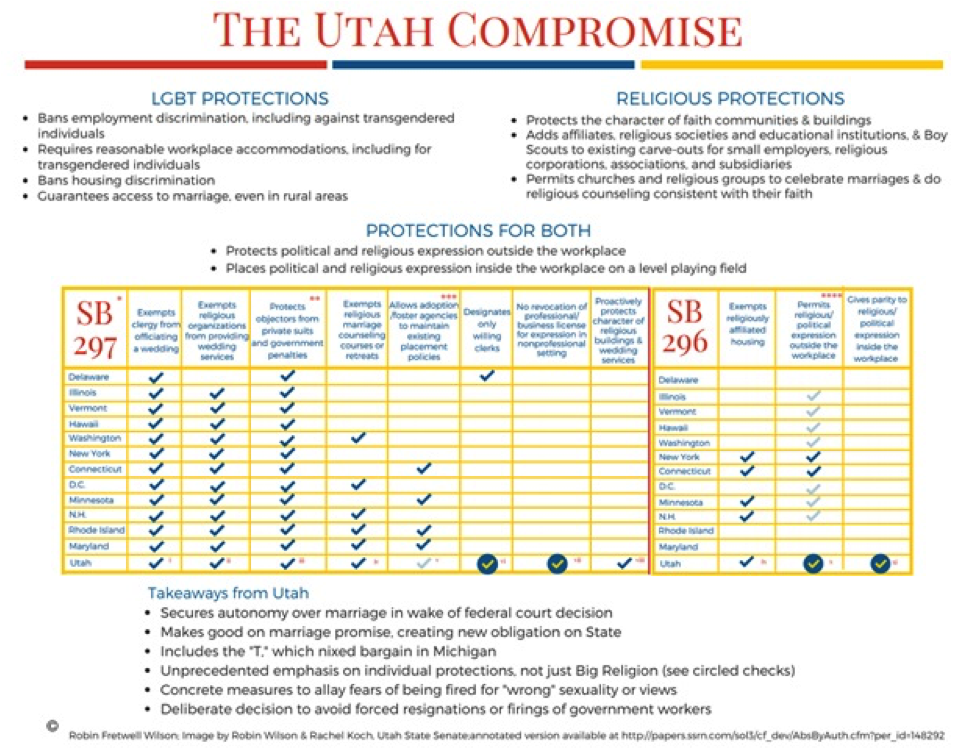

The idea came from Mormon-dominated Utah, which was hailed in 2015 for passing compromise bills banning forms of LGBT discrimination but also codifying rights for religious expression.

“We observed what Utah did last March, that they were able to secure more religious liberties than any state that had legislatively proposed gay marriage by combining civil rights protections for LGBT persons and religious liberties,” LoMaglio said. “Then we observed a few weeks later in Indiana the eruption of negative public relations around religious liberty when Indiana tried to expand their scope of their Religious Freedom Restoration Act bill without extending protections to LGBT persons.”

Connecticut and New York banned state-funded travel to Indiana. The band Wilco and comedian Nick Offerman canceled Indianapolis performances, and the Indianapolis-headquartered NCAA said the law “might affect future events as well as our workforce.” Vice President-elect Mike Pence, then governor of Indiana, was pressured into signing an amended bill that actually eroded religious liberty, particularly for business owners.

The Indiana controversy hurt “both the cause and the public understanding of what religious freedom actually is,” LoMaglio said. “We wondered what it might look like to do at the federal level what Utah did at the state level.”

Acting months before the Obergefell decision in June 2015 that mandated same-sex marriage nationwide, Utah gave LGBT people the right to equal housing, and employment, and protected employee speech for all political and religious views, whether supportive of same-sex or traditional marriage. At the same time, the state exempted clergy who officiate weddings, religious organizations that provide wedding services, and religious marriage counselors who offer courses and retreats.

It protected objectors to same-sex marriage from private lawsuits and government penalties, allowed adoption agencies to set their own placement policies, and said only willing government clerks should be the ones signing same-sex marriage licenses.

In addition, the state said no business or professional license could be revoked from a person who expressed his or her opinion outside of work, and protected religious buildings and wedding services from being forced to accommodate all ceremonies.

Tackling the question of how expanded SOGI rights and religious liberty protections intersect head-on would prevent “leaving those questions to chance,” LoMaglio said. After studying similar First Amendment cases that have come before the Supreme Court, CCCU leaders emphasized in meetings with member schools that courts often defer to legislation. The Supreme Court announced last month that it will consider whether public schools can be required to let students use bathrooms that match their gender identity.

Along with faith leaders, the CCCU also talked with LGBT rights advocates.

“Could we come to an arrangement that secured the level of religious freedom protections that our institutions need but would also be something that [LGBT advocates] could support?” LoMaglio asked. “We’re optimistic. We’re in the middle of a series of discussions.”

Using legislation—rather than the courts—to settle the issue is like using “a scalpel and not a hatchet” to craft protections for both groups, she said. “By doing it legislatively, we can ensure that religious organizations can hire for mission, and in the case of our institutions, can factor a student’s religion into their admission, or include religious requirements as part of their curriculum.”

The conflict between religious liberty and LGBT rights has been generally presented as an all-or-nothing fight, but it doesn’t have to be, LoMaglio said. “It’s possible for the Constitution to protect both of them. That’s what Utah did.”

A move to protect both “gets us out of this winner-take-all paradigm and brings it to a different lens, one that allows a pluralistic society to exist peaceably,” she said. “It also allows the good name of religious liberty to be reclaimed—as something that does not mean that one person’s claiming of religious liberty has to come at the expense of another person not having rights. They can both exist.”

Preparing for Change

But not everyone is on board.

The ERLC is opposed to the proposal, for the same reasons it didn’t like the Utah compromise, spokeswoman Elizabeth Bristow said.

“The bill is well intentioned,” Andrew Walker and Russell Moore wrote of the Utah legislation. “But this bill leaves wholly unprotected private, for-profit business owners who want to run their business according to their faith.”

The law protected businesses with 15 or fewer employees, which the ERLC found an “arbitrary threshold.” There were also “no guarantees that the bill would not someday be amended to either reduce the threshold or eliminate it altogether.”

So a Christian T-shirt printing company with more than 17 employees would have to print messages it found morally objectionable, Walker and Moore wrote.

Robin Fretwell Wilson, a University of Illinois law professor who helped craft the Utah legislation, said some of Walker and Moore’s characterization “simply misunderstands” the law.

Private business owners aren't protected by the law because they don't need it, she said.

“The Utah law did not reach as far as other state SOGI laws passed by Democratic legislatures,” she said. “It did not place affirmative duties in the public accommodations realm, so there was nothing to be protected against.”

And the protections will stand since they “rest on a balance of competing interests,” Wilson wrote in a February paper on bargaining for civil rights. “We haven’t seen exemptions rolled back” so far, she told TGC.

But Walker and Moore also said that language that seems to mark “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” as specific categories “works drastically against religious communities who do not agree with this viewpoint on matters of legal principal.”

“If a court were to hold that ‘gender identity’ and ‘sexual orientation’ are classes protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, it is unlikely that that grant would give any protection to churches or religious organizations,” they wrote.

Finally, the bill “aids and abets” the cultural movement to sideline the Christian view of traditional marriage and sexual behavior, Walker and Moore wrote. “The symbolism of this law represents an historic and incremental concession to those who would leave no room in the public square for those who refuse to bow down before, or offer sacrifices to, the false gods of the Sexual Revolution.”

The ERLC’s concerns are legitimate, said Chip Pollard, president of John Brown University and chair of the CCCU board. “The objections raised by groups [like ERLC] are fair and would have to be worked out. That’s why we held these meetings—to get different opinions.”

The ERLC’s concerns are legitimate, said Chip Pollard, president of John Brown University and chair of the CCCU board. “The objections raised by groups [like ERLC] are fair and would have to be worked out. That’s why we held these meetings—to get different opinions.”

Some of the objections—such as the questions about protecting for-profit business owners—depend on the details of the legislation, which have not yet been proposed, he said.

The worries about designating SOGI as a protected class and being seen as championing their rights are also worth considering, he said. But Dennis Hollinger, president of Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Massachusetts and an ethicist, insists that the Fairness for All approach advocated by the CCCU and NAE does not compromise Christian ethics.

“Our foremost concern should be to ensure that the church and Christian institutions have the right to carry out our biblical convictions without compromise,” Hollinger told TGC. “We recognize that granting rights in a secular, pluralistic society is not the same thing as our call to live in accordance to a Christian ethic. The Fairness for All approach is a strategy to ensure religious liberty, not a statement about certain practices in our society.”

And while Republicans take over the executive branch in Washington in January, that doesn’t mean that religious individuals and institutions are safe, Pollard said. States can still pass their own restrictions, and federal power could shift in two or four years. Plus, Hollinger said, no one knows for sure President-elect Donald Trump’s views on these matters. During the campaign he offered differing takes on the controversial North Carolina “bathroom bill,” and after his election he described the Obergefell decision as “settled law.” Still, gay-rights groups could see Republican power as reason to seek compromise.

“In Utah, the compromise happened in a state that was Republican-controlled,” said Pollard of John Brown University. “It may only be possible in a Republican-controlled situation.”

For those reasons, exploring a compromise is worth doing, Pollard said.

Philip Ryken, president of Wheaton College, declined to comment “because the conversation is in its early stages.”

David Dockery, president of Trinity International University, was hesitant to support the proposal yet.

“I have concerns about the Fairness for All proposal,” he said. “But I think we should all look for ways to work together for the best future for our shared work in Christian higher education.”

Whether or not the legislation ever arrives on President-elect Trump’s desk, Christian college and seminary presidents are preparing for change. Almost 50 percent of students at Gordon-Conwell use federal loans, Hollinger said, and the school is seeking other funding sources. Still, he remains optimistic about the possibilities of Christian education and witness, even if hostility toward biblical sexual ethics does not ebb.

“It’s also helpful to remember that Christian growth and vitality is not dependent on the status of the church in a given society,” Hollinger said. “The greatest growth and vitality around the world is occurring in places of opposition and hostility. We certainly want to reserve our right to proclaim the gospel and live out our biblical commitments, but even in the face of opposition God is powerfully at work.”

Editors’ note: This article was updated at 1:13 p.m. CST on November 25.

Free eBook by Tim Keller: ‘The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness’

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

In Tim Keller’s short ebook, The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path To True Christian Joy, he explains how to overcome the toxic tendencies of our age一not by diluting biblical truth or denying our differences一but by rooting our identity in Christ.

TGC is offering this Keller resource for free, so you can discover the “blessed rest” that only self-forgetfulness brings.