When Taisiia Lukich didn’t hear back from her boyfriend last October, she wasn’t worried.

“It was not first time he didn’t answer me for a long time because, you know, there are a lot of broken internet and cell phone connections,” said Taisiia, who is TGC Ukraine’s editor. Before the Russian invasion, she and her boyfriend, Alex, had been thinking about a 2022 wedding. Instead, she spent much of 2022 as a refugee, while Alex joined the Ukrainian army.

After four days of unanswered messages, Taisiia heard from Alex’s friend. He told her not to write anymore.

Alex had been killed in combat.

Taisiia fell apart. She stopped eating, stopped sleeping. Because Alex’s body was disfigured, his casket was closed at the funeral, and she wondered if he was really in there. Furious with God, she threw up lots of angry prayers and quit reading her Bible.

“I felt like I was falling into a pit of grief and sorrow and crying and pain,” she said. “I felt like I had no future anymore, that there was no reason to live my life. Some days I was so empty I couldn’t even talk to other people.”

She didn’t tell many friends at church, because it hurt too much to talk about and because she knew they were struggling with the same thing. Four of her church members have been killed in action; another 14 are serving in the military.

“One day, when I no longer had the strength to endure what was going on inside of me, I prayed, asking God for all that love and peace and comfort he had for me,” she said. She fell asleep in tears but woke up renewed. It felt like a miracle.

“Often in difficult situations we pay attention only to the pain this world has given us,” she said. “We forget to look at Christ, who knew from the beginning of the centuries this pain would be in our lives. He has already prepared comfort for us precisely for these situations.”

That truth is playing out all over the Ukrainian church. It’s been exactly a year since Russian forces began what president Vladimir Putin calls a “special military operation” to “demilitarize” and “denazify” Ukraine. In that time, his forces have destroyed and looted hundreds of church buildings. Along the shifting front lines, churches have emptied as members are killed, flee, or join the fighting.

But if you talk to Ukrainian Christians, they’ll tell you God hasn’t abandoned them. Many churches—along with some seminaries—are growing. Ukrainian refugees are revitalizing churches in other countries. And churches around the world have rallied to welcome Ukrainian refugees or send support.

“War is a time when you see the worst and best of people,” said Caleb Suko, an American missionary who has been in Ukraine for the past 20 years. “We have seen the best of what God does.”

Escape

Because Russia had been rumbling around the borders for so long, last year’s February 24 invasion surprised a lot of Ukrainians. Taisiia, who lives near a military base less than seven miles from Kyiv, woke up to six missed calls from Alex and more calls and messages from other friends.

Why am I so popular today? she wondered. “I started to open the messages and saw, OK, it’s war.”

Taisiia didn’t know what to do. She and her mom stocked up on water and hung heavy blankets on the windows. They went to church to ask what everyone else was doing. They went to the grocery store but nearly everything was bought out—although that was OK for Taisiia.

“My grandma experienced World War II, so she had a habit to stock some grains and porridges, so we actually had some food,” she said. She started to bake bread for people in her church and neighborhood.

On Saturday, tanks began rolling down the streets in Taisiia’s neighborhood. Ukrainian forces blew up the bridge to Kyiv—the blast knocked down the ceiling in her bedroom. About a week later, the fighter jets were coming in so low that Taisiia and her mom could feel each pass. They could hear explosions.

“My friend called and started yelling, asking why I was still here,” she said. She knew why—to help at her church—but she also knew she was responsible for her mother’s safety. Packing up her laptop, some spare clothes, and her cat, Taisiia and her mom headed for church, where the leader of her small group drove them as far as he could.

It wasn’t far. Since the bridge was out, Taisiia and her mom had to make their way on foot. Her mother fell on some rocks, soaking her clothes.

“After we crossed the river, the enemy artillery started to fire,” Taisiia said. “Now we are standing in open space. There is nothing to hide behind. You’re just standing there praying, ‘Please, God, not now.’”

Ukrainian forces returned fire, and the Russian guns paused. Taisiia was on her way.

Trapped

Within a matter of days, Russian forces grabbed a swath of Ukraine’s land, including the city of Balakliya where a pastor named Oleksandr lived. His church was large, with a lot of young families. He started driving, bringing people out of Russian-controlled territory and bringing food back in.

“When we did the Sunday service, I just saw fear in people,” he said in a recorded conversation. He stayed because “when you’re near them as a pastor, as a minister, it just inspired people.”

At the beginning of May, he tried to get through to Kyiv for a pastors’ conference and was turned back. A few days later, Russian forces came to his home and told him to get into their car.

They took him to the police station, and Oleksandr knew he was in trouble when they dropped a bag over his head. Over the next two days, he was beaten severely.

“At first I didn’t know what they wanted from me,” he said. “And then I began to realize, first of all, these people—this man who is conducting the interrogation—he just chronically hates all Protestants. He was making it clear and saying, ‘We won’t let you live here. There will only be one church here—the Russian Orthodox Church.’”

Later, the Russians accused Oleksandr of working for American intelligence. They hit and kicked him everywhere, bruising his whole body and breaking his left arm.

Oleksandr prayed to the God he knew released Peter from prison and Daniel from the lion’s den. “I felt that God was silent,” he said. “It was awful. That is the moment you need God to speak, and he was silent.”

Oleksandr’s wounds were so severe he was taken to the medical center across the street. After a two-week stay there, his wife was allowed to bring him home. That release “showed [God] was with me, he showed his faithfulness,” he said. “And I realized that when God is silent, it doesn’t mean he’s not there.”

When God is silent, it doesn’t mean he’s not there.

Balakliya was liberated by Ukrainian forces on September 8, and the torture chamber in the police station basement was discovered. Oleksandr’s church got their building back, and they immediately began to distribute humanitarian aid, tape up windows, and pray with people.

“Now there are many people who come to Sunday service,” Oleksandr said. “They just want to fellowship with us. They want to spend time with us.”

The church members are more mature, his wife added. While some are just trying to make it through the day, others have grown in faith. “They’re tired, they’re falling down, but they’re preaching, they’re ministering,” she said. “It makes my heart happy, and I just admire the courage. I admire the fortitude of believers.”

Oleksandr is praying for his church but also for his former captors.

“If at least one person [in the prison] heard the gospel and was somehow touched by it, give him repentance, and I want to see this man in the kingdom of heaven,” he said. “And it will be a great joy for me, if I come to the kingdom of heaven and see one of these who have repented before God.”

On the Run

While Oleksandr was in the police station basement, many of his church members were scattering across Ukraine and neighboring countries. To date, about a third of Ukrainians have been displaced—8 million of them are spread out across Europe.

“On March 7, we didn’t plan to move,” said seminary professor Vasyl Novakovets. “On March 8, we were in the car.”

Vasyl lived in Odessa, which is a strategic target for Russia. With their three kids between the ages of 6 and 11, his wife was scared to stay. After a day of prayers and phone calls, a way opened for the family to escape to Romania. They stayed for a while at a Christian center, then moved on to Austria.

“You have some clothes for yourself and your children, and you go,” he said. “The first few weeks were very bad, very stressful. We didn’t know how long we would be [anywhere]. [In Austria], the German language was new. Our kids went to school but didn’t understand anything. For a week, I couldn’t even bring myself to read the Bible. It was very bad.”

Slowly, God provided new friends to talk and pray with, Vasyl said. He found a Ukrainian-speaking church where he could preach regularly and join a small group.

“In dark times, you move closer to God,” he said. “You really depend on him because you don’t know what will happen the next day or the next month. But God opened new opportunities, new ministries, new support. If somebody asked me, ‘Would you like to repeat this time?’ I’d say yes, because it was hard, but it’s brought me so close to God.”

In December, Vasyl’s family moved to Pennsylvania, where he connected with a Ukrainian-speaking church he knew well. Back in 2015, he’d begun a project with member Roman Kapran, who preceded him as a refugee 23 years ago, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Roman is now the president of the Ukrainian Baptist Convention of the U.S. He was working on the first Ukrainian study Bible when, in 2015, the publisher Crossway granted permission for a Ukrainian translation of the ESV study Bible notes.

After seven years of working with Vasyl and other Ukrainian theologians, the work was almost complete when the war began. The translators took a few months to restabilize their lives and are now finishing up the edits and looking fors enough funds to print—a cost of about $50,000, Roman estimated. Their last meeting was in December on Zoom, with Ukrainian participants logging in from across Western Europe and the United States.

In that call, Vasyl could see God at work—and not just in the work they’d accomplished together.

“My friends are now missionaries to Holland, Germany, Slovak, Romania, and Poland,” he said. “Ukrainian people are now in these countries, and these leaders are trying to share the gospel and help them.”

Receiving Refugees

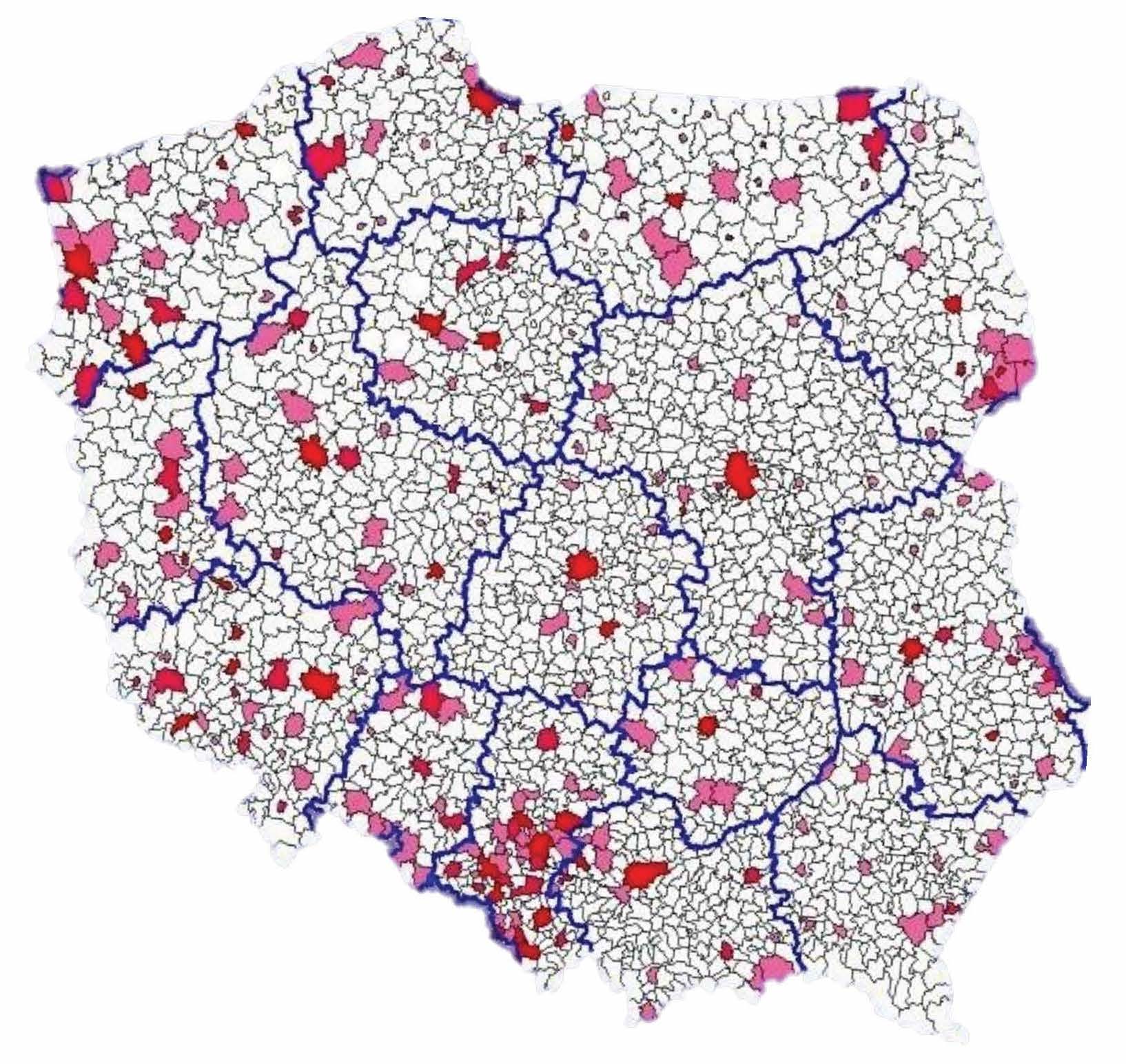

Aleksander Saško Nezamutdinov came to faith in a Ukrainian evangelical church when he was 12. While in Bible college, he was considering mission work in former Yugoslavia—until someone showed him a map of Poland with Protestant presence marked in red.

“The whole map was so white, so blank—almost empty,” he said. So Saško did an internship with the Presbyterian Church in America’s Mission to the World (MTW) team, then started a church planting project in Kraków. His church of 20 members doubled to 40 during the pandemic, squeezing into an 800-square foot rented storefront.

From there, Saško watched Western diplomats leave Kyiv in January and February 2022, then saw larger mission agencies start to pull personnel.

“Then you know something’s coming,” he said. It came. As Russia pushed in with air strikes, missiles, and troops, Ukrainians headed the other direction. Over the last year, there have been more than 9.5 million border crossings from Ukraine into Poland.

Saško’s church saw its first refugees two days after the invasion. About 10 Ukrainian women showed up to Sunday services—he had to scramble to find chairs for them all.

“The following week was the hardest,” Saško said. “I kept receiving calls from Ukrainians wanting to get out through Kraków, and calls from Polish friends offering help. That whole week I was constantly on the phone.”

Some refugees needed a place to stay for a few hours while waiting for a train or airplane. Some needed to stay a few nights. Some knew where they were going; others had no idea. Some needed food, clothes, or strollers. Everybody needed prayers and comfort.

“The response of Poland has been incredible,” Saško said. “In the history of Europe, we haven’t seen anything like this. There was a point in those first few weeks when there were more Polish people at the border waiting with cars to offer people rides than there were Ukrainian people needing rides.”

Poland’s generosity stems from a strong historical memory, he said. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Soviet Russia was just a few weeks behind them, and the two countries carved up Poland between them.

“Poland remembers what it is like when there is nobody there to help you,” Saško said. Eager to assist, his congregants rented another building, then bought some beds. They hosted refugees, arranged transportation, and sorted food and clothing. When the first wave of refugees was through and things were settling down, Saško’s congregation rented a school and ran a 10-week VBS for kids during the summer.

Saško had been publishing theological texts in Polish; last summer, he added Ukrainian. So far, he’s printed 60,000 copies of titles such as John Piper’s Fifty Reasons Why Jesus Came to Die and R. C. Sproul’s The Donkey Who Carried a King. Some books went back into Ukraine, while others went to Polish, Czech, or German churches with Ukrainian refugees.

“It was like Jesus feeding the multitude with a limited number of fish and bread,” he said. “The apostles didn’t produce the food. Their responsibility was to distribute it. I felt like our church was doing that over the past year. The resources we never could have had or dreamed of were sent to us so we could use them.”

Saško’s 40 church members couldn’t do this all by themselves. MTW sent missionaries—something Saško’s been praying for since 2015. And the refugees themselves helped. “I don’t think there’s a church in Poland that doesn’t have a Ukrainian family,” he said. “Churches doubled in size. It’s really encouraging for Polish evangelicalism.”

Saško’s church sees about 60 people every Sunday now.

“If all the Ukrainians stay here, this will drastically change the religious map,” he said. It’s already changed Saško himself.

“My faith is stronger because of the faithfulness of God I’ve seen in real life,” he said. “This is incredible—the strongest manifestation of his work I’ve seen.”

Back in Ukraine

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine was—of all the former U.S.S.R. countries—the most open to the gospel.

“If you were handing out a box of Bibles in the 1990s, they’d be gone in two minutes,” said Caleb Suko, who made his first trip there in 1994. “There were huge revivals, and a lot of churches were built.”

Today, Ukraine has between 3,000 and 4,000 evangelical churches, estimated Rick Perhai, professor and director of advanced degrees at Kyiv Theological Seminary. So many that Ukraine is known as the “Bible belt” of the region.

“By the mid-2000s, a lot of that was slowing down,” said Caleb, who moved to Ukraine permanently in 2007. “The next generation was being trained up in the churches. People were busier. Ukraine was slowly becoming wealthier—you had malls and coffee shops and technology.”

When the Ukrainian president decided not to sign an agreement with the European Union in 2014, that led to violent protests in Kyiv and a Russian move to take Crimea. “We saw somewhat of a spiritual revival then,” Caleb said. “That lasted through 2014 and 2015.”

But that crisis was small compared to this one. “We see a huge openness to the gospel and huge needs this time,” he said.

While the harvest is ready, workers are few.

“Even our academic dean has been called up to the war,” Rick said. Realizing students in a war zone probably don’t have the headspace for a bachelors or masters degree, Kyiv Theological Seminary began offering a one-year certificate program. Done primarily in person, it helps students “get a taste of what the gospel is about and handle Scripture rightly,” Rick said.

The certificate program was first offered last fall. About 150 students enrolled—twice as many as the 65 students normally enrolled in the entire bachelors program.

These young pastors have a challenging job—in one church of 80 members, fewer than 20 are left. Everyone is worried and angry; one man who lost his son in the war is wrestling through desires for vengeance. In another church, 75 percent of the congregants fled. The pastor is sharing the gospel with refugees.

“Some of the refugees have been saved,” Rick said. “Now they’re being discipled, and some will soon be baptized. . . . The ministry has just blown up in a positive sense—exploded with multiplication and fruitfulness.”

Shadows of Mordor

If you drive across Ukraine from west to east, you’ll see increasing signs of destruction—buildings bombed out, bridges blown up, piles of rubble.

“It feels like you’re driving in Gondor, and you can see Mordor,” Rick said. “There are a lot of shadows of Mordor here, but there is hope in the midst of that.”

Taisiia feels that. After a stint in Slovakia, helping refugees at a Youth for Christ facility, she and her mom returned to their home near Kyiv.

“A missile struck our basement, and now we have a huge hole in it,” she said. “There are missing windows and some more ceilings fell down.”

But it felt so good to be home, she said. These days, Taisiia is back at church, volunteering. She’s working several jobs, including translating and editing articles for TGC.

“Without the journey inside of the darkest places in my soul, I’d never be at the point where I’m comforted, happy, loving again,” she said. “God gave comfort in that moment where I stopped hoping that I would ever have comfort. I was so shut up in my desperate thoughts that I forgot that God gave up his Son. I had no right to say nobody understands me—he does understand, even more than I think he can.”

She keeps reminding herself God has more plans for her. “If God didn’t take my life today, it means probably he has something for me to do tomorrow.”

Her Christian brothers and sisters echo that.

To minister in Ukraine right now “is not easy at all—it is really, really hard,” Rick said. “But it’s basically taking God at his word, doing what he says to do, and believing that his Word is living and active and his Spirit is going to move in the hearts of his elect.”

“God gives us grace,” said Caleb, who has been regularly handing out food and blankets to hundreds of people. “We know where he called us to, so that’s definitely where we want to be. We wouldn’t want to be anywhere else right now.”

In 2022, TGC launched websites in Ukrainian and in Russian to support Christians there. Read TGC’s report on what God has been doing in Russia.

Share gospel-centered resources with the global church

It is our prayer that God will increase the reach and the impact of TGC’s international work to provide trusted and timely, winsome and wise, gospel–centered resources to the global church. Will you join us in this mission? Your gift will be a great encouragement to the afflicted church across the world.

Click the button below to support the global Church

Donate Today »