In 2005, flush with revenue from $100-plus barrels of oil, the Saudi Arabian government set up a $6 billion scholarship fund.

The program covers full tuition, medical insurance, living expenses, and airfare for both undergraduate and graduate students. The only catch: students are required to study at one of the world’s top 100 universities, or enroll in a top-50 program.

Ever since, the number of Saudi students coming to study in the United States has steadily risen, from about 3,400 in 2005–2006 to more than 60,000 in 2015–2016. Led by Ivy League universities, the United States appears most often on every list of top global schools.

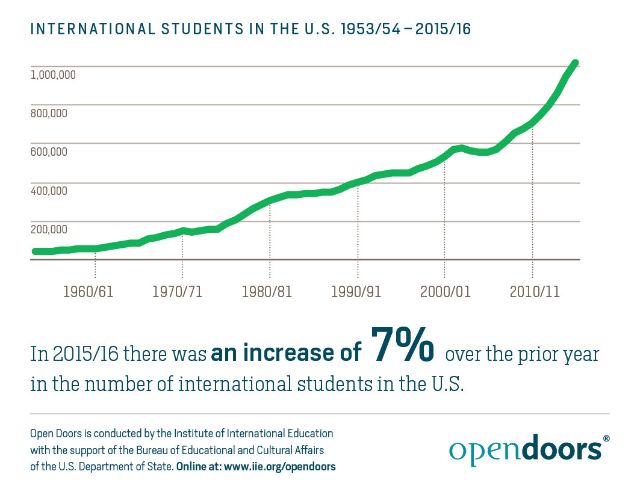

Alongside the rise of the global standard of living, the quality of American higher education, and the eagerness of American universities to accept international students who pay full tuition, scholarship programs like Saudi Arabia’s have led to a rapid increase in foreign students in the States. The number jumped from around 500,000 in 2000 to more than a million this year.

The continuance of the trend is now uncertain, given President Donald Trump’s border-tightening executive orders (which TGC explains here). Saudi Arabia was not included in the seven majority-Muslim nations whose citizens and immigrants are temporarily banned from entering the country. Iran, which sent more than 12,000 students to the U.S. last year, is.

The continuance of the trend is now uncertain, given President Donald Trump’s border-tightening executive orders (which TGC explains here). Saudi Arabia was not included in the seven majority-Muslim nations whose citizens and immigrants are temporarily banned from entering the country. Iran, which sent more than 12,000 students to the U.S. last year, is.

“It is disheartening and angering,” said Marc Papai, director of international student ministry at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. “It will have a chilling effect obviously for Muslim students coming to the United States, but to other internationals as well.”

The ban adds another challenge to campus ministries already racing to keep up—with the increasing number of students and with their changes in age, needs, and cultural backgrounds.

Perfect Opportunity

The foreign students flooding into U.S. universities are, in some ways, the ideal ministry field.

Many are bright and affluent, able to afford some of the world’s top schools. That means they’re also likely future leaders, one day returning home to take influential positions. And generally comfortable with and curious about religion, they’re not hampered by the apathy or antagonism some American students feel toward Christianity.

Their influence can be far-reaching.

For example, Chinese scholars have gone home to teach Reformed University Fellowship (RUF) materials in Bible classes in public universities, something no Western missionary could do, said RUF International (RUF-I) coordinator Al LaCour.

One Indian student returned to a professorship at a prestigious university and began “speaking at professional and Christian conferences around the country, bearing faithful witness to the Kingdom in the highest reaches of Indian universities,” Papai said.

And a University of California, Berkeley, student from Uganda went on to lead in his government. In turn, he sent his sons to the United States for school, one of whom met Bridges International director Trae Vacek. They grew close, and Vacek is now his baby’s godfather.

“This is our ministry lived out 30 years later,” Vacek said. “There is so much potential in students who will be leaders tomorrow.”

Scrambling to Keep Up

In the last 10 years, five RUF-I campus ministries have grown to 13, and leadership is aiming for a new one at Northwestern University next fall—a strategic choice, since Northwestern was recently ranked 26th on the Shanghai list of top universities.

“For 10 years, RUF-I had to go where campus ministers and money were available,” LaCour said. “Now the churches are having epiphanies. RUF is embracing our international student ministry.”

RUF isn’t the only one.

In January, Chi Alpha rolled out an initiative that acknowledges both the work God is doing among international students and the responsibility of Christian students to intentionally engage them.

And almost all of InterVarsity’s 1,000 chapters now contain at least one international student, said Papai.

But the fastest-growing outreach program is Bridges International, an outreach of Cru (formerly Campus Crusade for Christ). The ministry formally organized in 2002 with 60 staff members; now there are 380 full-time and nearly 600 part-time staff and student laborers. A recent conference for international students saw more than 1,100 attendees from 64 nations.

Vacek said the growth “really wasn’t a response like, ‘Hey, there’s more students. We need to put more staff on it.’ It was people within Cru who have a heart for the world but weren’t able to get on a plane to Asia or allowed to walk the streets in the Middle East.”

How to Reach Internationals

Unlike students of 15 years ago, today’s international students usually don’t need hand-me-down couches or money for books. “Our Chinese and Saudi students are coming in asking where the car dealership is,” said Severin Lwali, an ambassador for international student ministry at Chi Alpha Campus Ministries. “You have to find different ways of loving and serving them.”

Almost all campus ministries seek to provide a welcoming home-away-from-home for students grappling not only with being away at college, but also culture shock.

Like American students, international students are looking for community. But they also need somewhere to go on American holidays, they need someone to celebrate their cultural holidays with them, and they need friends.

“Welcoming them is biblical hospitality,” LaCour said. RUF-I picks up students from the airport, celebrates Chinese New Year, and observes the Indian Diwali festival of lights.

RUF-I also encourages the engagement of the local church. One small church in the Atlanta area invited 75 international students at Georgia Tech to an afternoon of boat rides and hamburgers. An elder at another small Georgia church slaughtered a goat so one of his African Muslim students could have a home-cooked meal.

InterVarsity has been experimenting with “peace feasts,” Papai said. “A peace feast is a gathering of a small group of Christian and Muslim students in equal numbers in a neutral place, often a restaurant. Everyone knows it will be an exchange of views about religion.”

The feasts work as a way to break down barriers of “mistrust or a lack of knowledge,” he said. Muslim students are “very willing to talk about religion, and are perplexed when American Christians seem to be shy or embarrassed about God.”

LaCour estimates that about 95 percent of the international students who come to RUF-I have never heard the gospel.

LaCour estimates that about 95 percent of the international students who come to RUF-I have never heard the gospel. So RUF-I at Southern Methodist University in Texas hosts about 55 a week for a free meal followed by an exploration of the Bible. Another 50 or 60 come to the same event at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Auburn University. The University of Delaware sees more than 95 international students regularly attend.

Folding international students in with American students also has benefits, Lwali said. “You want them to understand, at the end of the day, that God is not an American god—that he is God of the whole world. And you want your American students to understand that as well. It’s a disservice we give to American students by putting [Christianity] only in their context.”

International students bring a fresh view of the gospel and boldness to religion discussions. In some cases, Papai said, they're the ones leading American students to Christ.

Changes in Age and Geography

When LaCour started working with international students 12 years ago, most were graduate students.

“I had mostly master’s students in computer science, and a lot of PhD candidates from China and India,” he said. Some came with spouses or families.

Now undergraduates make up the largest group of international students, growing by 7 percent over the past two years to break 400,000.

And while China continues to outpace any other sending country (more than 320,000 students this year; India followed with nearly 166,000), Saudi Arabia’s scholarship shot it to third for the first time this year. South Korea follows close behind.

“If you think about it from a missional standpoint, the top three places are all within the 10-40 window,” Vacek said.

‘The top three places [sending students to America] are all within the 10-40 window.’

The rise of the Asian and South Asian economy has changed the composition of international students, LaCour said. Taiwan, Japan, and Vietnam are in the top 10 sending countries this year; Nepal, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Thailand are all in the top 25.

With so many cultural and religious backgrounds, international ministry isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. But ministry leaders have noticed some trends.

In general, Chinese students are the most open to the gospel. Papai estimated that about two-thirds of the students who come to faith through InterVarsity are Chinese.

Hindu students are more difficult, since it’s easy for them to “sweep Jesus in with the rest of the gods,” LaCour said. And Muslim students, while wary of Christian evangelism, are sometimes disillusioned with the conservative Islam practiced in the Middle East and by ISIS.

“There are a lot of disenfranchised Muslims out there inquiring,” LaCour said.

The strong intellectual heritage of Iran and Pakistan means many students from those countries are curious about faith, Papai said.

Conversations with international students “are not loaded with assumptions” the way conversations with American students are, Lwali said. “They’re asking, ‘Who actually is Jesus? Why is he so important? What is this book you keep referencing, and why should I read it?’”

It can also be helpful that many international students associate the United States with Christianity.

“Because there is no separation of the mosque and government in Muslim countries, and in China the government also controls religion, international students often assume it’s the same way here,” Papai said. “Because of that, when international students think about getting to know America, they think about getting to know our religion, and they connect that with Protestant Christianity. They want to explore the Christian faith and so in that sense, the globalization phenomenon has been good.”

Keeping the Faith by Equipping Leaders

“Chinese students dominate the landscape in terms of numbers,” Papai said. “God has been doing a miracle work among them over the last 50 to 70 years in their country and here in the United States.”

However, “four out of five Chinese students who come to faith in the United States or another Western country don’t stay in the faith after a couple of years once they’re home in China,” he said. “There are a number of reasons for that, but what we are keen on is doing a much better job of preparing for students for their return.”

To that end, this fall InterVarsity started a longitudinal study tracking international students after they return home in order to discover the challenges they face.

Until then, InterVarsity and others are working to disciple international students and help them form strong faith habits, Papai said. They’re also taking another look at leadership.

In the past, campus ministries have done a disservice to international students by “preparing events for them or doing ministry to them,” he said.

Bridges was noticing the same thing.

“We did realize about five years ago that our returnees were struggling as well,” Vacek said. “Everyone on this side of the ocean was seeing that we were serving our students a little too much.”

“There is nothing about sitting in a large group that helps prepare them for going back to China or Saudi Arabia as a believer,” Lwali said. “If we don’t have a vision for that, we won’t make on-ramps for them to move into leadership, and we’ll be missing out on the opportunity.”

It’s tricky, since international students feel like guests and, in many cultures, volunteering oneself to share a testimony or lead worship smacks of pride. So asking a room full of American and international students for volunteers is only going to garner American leadership, Lwali said.

International students need both examples of others like them leading and explicit permission to do it themselves, he said.

Campus ministries are also working to connect students with chapters or local churches in their home countries, Papai said.

More to Go

“I think God desires every one of those million international students to hear a credible presentation of the gospel,” Papai said. “With our sister organizations, we may be affecting 30,000 to 40,000 in a meaningful way. That leaves the vast majority untouched.”

Barring more restrictive orders from the White House, the numbers are likely to rise, spurred on by the economic reality that international students spent nearly $33 billion and supported more than 400,000 jobs in the United States in the 2015–2016 school year alone.

“The challenge is helping the evangelical church see the mission field right under our nose,” LaCour said.

“There have never been more international students in the United States than there are right now. . . . It feels like a spiritual moment in history that doesn’t come along that often.”

The Bible is full of stories of the ways God works through foreigners, including Rahab, Ruth, and the Magi, he said. “God continues to send resident foreigners among his people to be divine interruptions of business as usual, to remind us that the promise to Abraham is for all the nations.”

International student ministry is “as easy as setting another plate at the dinner table,” Vacek said. “But you have to take the initiative.”

“The opportunities are unprecedented,” Papai said. “There have never been more international students in the United States than there are right now. And the church in America, for all it lacks, is still robust. . . . It feels like a spiritual moment in history that doesn’t come along that often.”

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.