Lyndal Roper—professor of history at Oxford—has written a new biography of Martin Luther titled Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet.

Her goal is neither to “idolize” nor “denigrate” Luther, nor does she “wish to make him consistent.” She aims instead to understand him and the “convulsions” both he and Protestantism in general unleashed (xxx). Roper examines Luther’s relationships with family, mentors, and students; his theological and pastoral concerns; and his sociological context to give readers a fuller picture of the man and his time.

Luther’s Relationships

Roper situates Luther in the complex of personal relationships of the Reformation. Especially prominent in her story are those she deems “father figures” for Luther—including his own father; his Augustinian superior, Johannes von Staupitz; and his colleague, Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt. After analyzing these relationships, Roper writes that Luther was unable to “transmit a sense of God’s fatherly care for the believer” (195). She concludes that “it is the distance, rather than the personal closeness, of God that lies at the center of Luther’s theology” (195). Yet this conclusion ignores the Reformer’s concept of the immediate, effective presence of God in his Word in all its forms, and his providential care for human beings in daily life.

Roper also treats Luther’s relationship with his mother, Margarete, and his wife, Katharina. His marriage had many features that are “chauvinist” from a modern perspective, but it was also loving, open, and in some aspects progressive (he left his possessions to her in his last will and testament despite that being against Saxon law).

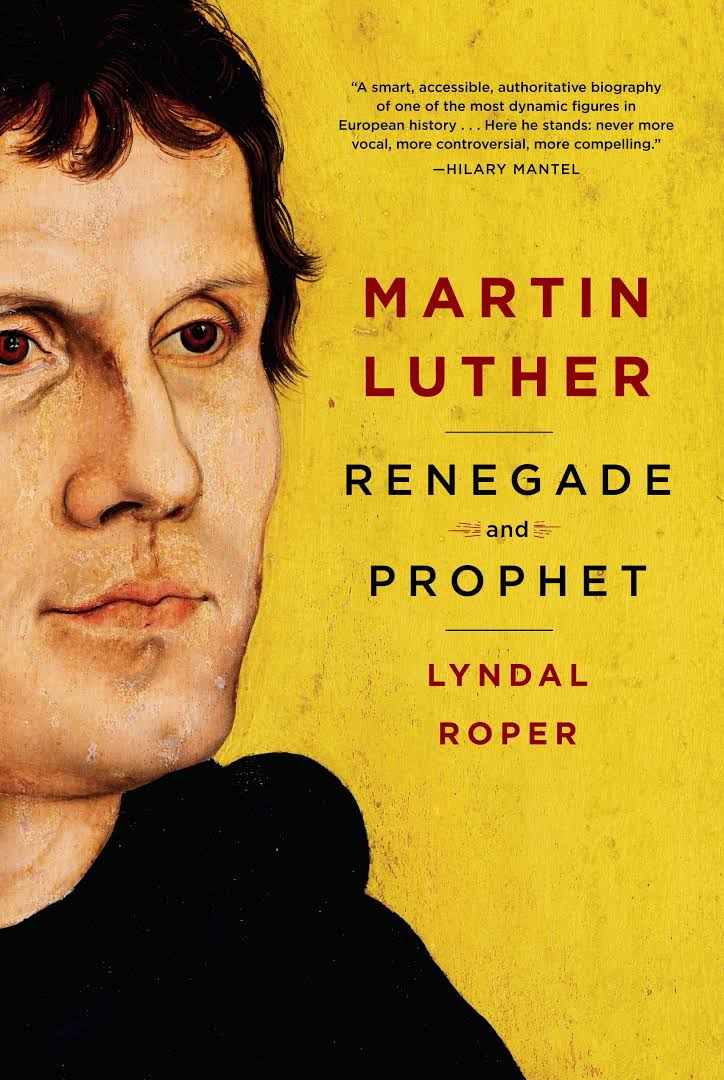

Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet

Lyndal Roper

Further, her treatment of Luther’s students is curiously lopsided. Roper focuses on one student with whom he had severe difficulties, Johann Agricola. Though she doesn’t ignore the theological side of their rupture, she could’ve made clearer how serious Agricola’s confusion of law and gospel was for Luther. She doesn’t counterbalance this story with examples of the warm relationships Luther enjoyed with many students who adored him. The book also could’ve benefited from a more thorough examination of Luther’s complex relationship with Philip Melanchthon.

Luther’s Context

Luther’s focus on the physical elements of God’s creation occupy Roper’s attention in several different arenas, including his understanding of Christ’s presence in the Lord’s Supper, his beliefs about the blessings and abuses of sexuality, and his often crude use of the physical in his polemic. It’s puzzling, then, that she doesn’t treat the Ockhamist tradition in which Luther was educated as part of the background for these attitudes. His doctrine of creation—derived at least in part from Ockhamist principles, and not only from his “radical Augustinianism”—accounts for much of Luther’s “remarkably uninhibited views about sexuality—and consequently marriage” (275).

Among the many strengths of this study are Roper’s illuminating sketches of Luther’s social and economic contexts—from his entrepreneurial family to the societal dynamics in Wittenberg to the political intricacies of the German empire. More than most Luther biographers, Roper highlights his thoughts on martryrdom, and her development of this thread is quite helpful. She captures the drama of the conflicts that marked Luther’s career, and her lively style keeps readers engaged throughout. Her thoughtful observations pierce through commonplaces on Luther. For example, she judges Luther’s rendering of the New Testament into German “a deeply personal translation that seems to have been written in a single breath” (197).

While Roper’s treatment of some issues is uneven, these bumps in the road didn’t interrupt my pleasure in reading the book. Although I would always like more discussions of Luther’s theology, Roper does pay attention to Luther’s theological concerns and takes them seriously. She sensitively depicts his pastoral care while presenting his rage against the enemies he perceived to be threatening the gospel. She understands that his “hatreds” cannot be fully grasped without reference to his passion for caring for God’s people.

For my students, I still prefer Scott Hendrix’s Martin Luther, Visionary Reformer for several reasons, including his greater emphasis on Luther’s thought. But instructors in Reformation studies should read Roper for a profitable expansion of their understanding of the man and his period. All who are interested in the German Reformer will gain new insights from this carefully crafted account.