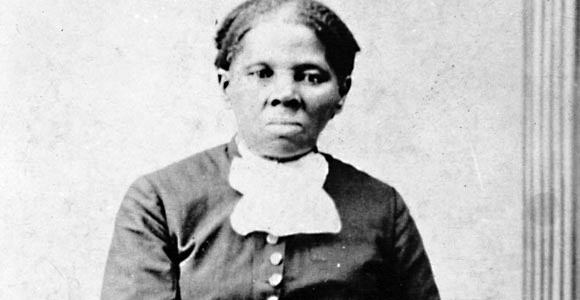

On Wednesday, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced that Harriet Tubman would be replacing President Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill. Here are nine things you should know about the legendary civil rights leader.

1. Harriet Tubman didn’t become “Harriet Tubman” until her mid-20s. She was originally born a slave named Araminta Ross on a plantation in Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The surname Tubman comes from her first husband, John Tubman, a free black man, and after marrying, she adopted the name “Harriet” after her mother: Harriet Ross.

2. A few years after she married, Tubman and two of her brothers initially escaped from slavery. However, when her brothers returned (one of them had recently become a father) she returned with them to the plantation. She would later escape again with the help of the Underground Railroad, a network of secret routes and safe houses used by abolitionists. Tubman later recalled how she felt upon arriving a free woman in Pennsylvania:

When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.

3. Since none of Tubman’s family was with her in Pennsylvania (her husband, John, stayed behind and would later remarry another woman), she returned on several trips to help lead her relatives to freedom. Over the next 15 years she would, with the help of others in the Underground Railroad, lead approximately 70 slaves out of their captivity. Her efforts in the dangerous undertaking earned her the nickname “Moses” by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who compared her to the Hebrew leader who lead his people out of slavery in Egypt.

4. By the late 1850s, Tubman had gained renown in the abolitionist community. J. W. Loguen, a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, said of her, “Among slaves she is better known than the Bible, for she circulates more freely.” Loguen introduced Tubman to the controversially violent abolitionist John Brown, who connected her to other influential leaders in the movement. Brown once introduced Tubman by saying, “I bring you one of the best and bravest persons on the continent—General Tubman, we call her.” Tubman would go on to become a powerful speaker for the antislavery movement.

5. During the Civil War, Tubman served the Union Army as a spy, helping map out areas of South Carolina. She became the only woman to lead men into battle during the Civil War when she guided a nighttime raid at Combahee Ferry in June 1863. While under fire, Tubman’s group freed more than 700 slaves from neighboring plantations. Both before and after her work as a spy she also served as a nurse and cook for the Army. Despite her service, Tubman never received a regular salary and was denied an official military pension. Tubman later became the beneficiary of military benefits, but only as the wife of an “official” veteran, her second husband, Nelson Davis.

6. After the Civil War Tubman became involved in other social reform movements, including temperance, women’s rights, and universal suffrage. Tubman once gave a speech alongside suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony and was introduced at the event as the “great Black liberator.” When a friend asked Tubman if women should have the right to vote she responded, “I’ve suffered enough to believe it.”

7. At a young age, Tubman suffered a traumatic head injury that caused her to have crippling headaches and disabling epileptic seizures. But it also gave her powerful visions, which, as a lifelong devout Christian, she attributed to God. The abolitionist Thomas Garrett once said about Tubman,

I never met with any person, of any color, who had more confidence in the voice of God, as spoken direct to her soul. She frequently told me that she talked with God, and he talked to her every day of her life . . . she said she never ventured only where God sent her, and her faith in the Supreme Power was truly great.

8. Throughout her life Tubman remained either in poverty or on the verge of destitution. She managed to scrape by on her labor, her husband’s pension, and donations from admirers. According to one biographer, she “never drew for herself more than 20 days’ rations” during the four years she labored during the war. Instead, she supported herself by selling pies, gingerbread, and root beer to soldiers. After the war, she used her reputation to help raise $2,000 on a scheme that turned out to be a con. Tubman had hoped to use the proceeds to open a home for black people but was instead attacked, bound, and gagged by the con men. Wisconsin Congressman Gerry W. Hazelton introduced legislation in 1874 that Tubman be paid “the sum of $2,000 for services rendered by her to the Union Army as scout, nurse, and spy,” but the bill was defeated.

9. From the proceeds of a biography written by a supporter, Tubman was able to buy a property with two buildings on 26 acres near her home in Auburn, New York. She later deeded the land to the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Zion Church, to be used as a home for the elderly (which she wanted to be named John Brown Hall). At the time she attended the mostly white Central Presbyterian Church, but she later became active in the A.M.E. church, where her husband was a trustee. In 1908, the A.M.E. Zion regional conference voted to take an annual collection for the maintenance of what was now called the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged. Tubman herself was the only female member on a board of trustees dominated by pastors. By 1911, she was so ill and impoverished that she was admitted to the home named after her. She died in 1913, with her last words being, “I go to prepare a place for you.”

Other articles in this series:

Autism • Seventh-day Adventism • Justice Antonin Scalia (1936–2016) • Female Genital Mutilation • Orphans • Pastors • Global Persecution of Christians (2015 Edition) • Global Hunger • National Hispanic Heritage Month • Pope Francis • Refugees in America • Margaret Sanger • Confederate Flag Controversy • Elisabeth Elliot • Animal Fighting • Mental Health • Prayer in the Bible • Same-sex Marriage • Genocide • Church Architecture • Auschwitz and Nazi Extermination Camps • Boko Haram • Adoption • Military Chaplains • Atheism • Intimate Partner Violence • Rabbinic Judaism • Hamas • Male Body Image Issues • Mormonism • Islam • Independence Day and the Declaration of Independence • Anglicanism • Transgenderism • Southern Baptist Convention • Surrogacy • John Calvin • The Rwandan Genocide • The Chronicles of Narnia • The Story of Noah • Fred Phelps and Westboro Baptist Church • Pimps and Sex Traffickers • Marriage in America • Black History Month • The Holocaust • Roe v. Wade • Poverty in America • Christmas • The Hobbit • Council of Trent • C.S. Lewis • Halloween and Reformation Day • Casinos and Gambling • Prison Rape • 6th Street Baptist Church Bombing • 9/11 Attack Aftermath • Chemical Weapons • March on Washington • Duck Dynasty • Child Brides • Human Trafficking • Scopes Monkey Trial • Social Media • Supreme Court's Same-Sex Marriage Cases • The Bible • Human Cloning • Pornography and the Brain • Planned Parenthood • Boston Marathon Bombing • Female Body Image Issues • Islamic State

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!