Richard Belcher introduces the principles of biblical interpretation. Belcher focuses on proper methods to understand the Bible’s text, emphasizing historical context, authorial intent, and theological consistency to guide listeners toward accurate exegesis.

The following unedited transcript is provided by Beluga AI.

This audio lecture is brought to you by RTs on iTunes U at the virtual campus of Reformed Theological Seminary. To listen to other lectures and to access additional resources, please visit us at itunes.rts.edu. For additional information on how to take distance education courses for credit towards a fully accredited Master of Arts in Religion degree, please visit our website at virtual.rts.edu.

Alright, so we’re at lecture three, and we’ve got several things to talk about this morning related to the interpretation of prophecy.

So this is a broad lecture that lays some foundations for what we’re going to look at all the rest of this course. How do you interpret prophecy? We’ll talk specifically about some things in this lecture, and then we may or may not pick up on some of these things specifically as we go throughout the prophets.

The first thing I want to talk about is the nature of prophecy. Is prophecy proclamation or is it prediction? Well, to one degree it’s both, but it does make a difference what you emphasize. Many emphasize prophecy as prediction.

That’s where all of their emphasis lies. Prophecy is about predicting the future in their view. And many understand prophecy in an absolute sense, in the sense that prophecy must be fulfilled in exactly the same way that it is given. So prophecy is stated, and then it must be fulfilled exactly the way that it is stated. And prophecy as prediction is sort of like launching a missile from back here in the Old Testament. That missile is launched and it hits its target over here, and nothing that happens in between here has any effect on the outcome.

So that’s one understanding of prophecy. We will come back and modify this later. I think it’s a misunderstanding, but we’ll come back and talk about and this is what Pratt’s article is all about, historical contingencies that may or may not affect a prophecy. So that would be, I think, a misunderstanding of prophecy. The other thing that’s helpful to talk about when we talk about misunderstanding prophecy is something that’s on the radar screen, at least recently in the theological world, and that’s open theism.

We need to spend a little bit of time here because of their view of prophecy. Open theism says that God changes his mind in response to how his creatures act and react. So instead of a prophecy being absolutely given and then hitting its target, and there being nothing in between that affects it, open theism says there are all kinds of things going on in between; it affects it, and God’s constantly changing his mind in relationship to how people react. I’ve given to you in your notes some bibliography, much more out there on open theism.

But these are some of the early foundational works. Gregory Boyd and John Sanders. Let me just very briefly lay out for you the view of open theism. Open theism believes the future is partly open and partly settled. So when you think about the future, it’s partly open, partly settled. The part about the future that is settled is related to God’s purpose and intentions. So there are some things about the future that are settled. They are related to the purposes of God and the intentions of God. But not everything about the future is settled.

The open part of the future relates to the free choices of individuals, and their definition of freedom is important. Here they define freedom as being able to choose, having the ability to choose between option a, b, or c. So human beings have the ability to choose among the variety of options, and their view of freedom is very important for their view. In general, they say, if people are genuinely free, then God cannot know ahead of time their future, freely chosen actions.

If God knows ahead of time how a person will choose, then that choice is not really free. In their understanding, these free decisions of human beings have not yet taken place. So there’s nothing to know. See, God knows the future, what there is to know about the future. But since these freely chosen decisions of these individuals have not yet taken place, then there’s nothing really to know. God does not know if a person will go this way or that way or this way, or choose this or that.

Boyd uses the analogy of a choose-your-own-adventure story. Choose your own ending, if you will, where a couple of alternatives might be appropriate, and the ending will depend on the free choice of the individual. So, God doesn’t necessarily know the ending because individuals have not yet made their free choices.

In the case of Peter’s denials, remember, Jesus told Peter that he would deny him before it happened. Well, in that situation, Jesus knew enough about Peter’s character to know that if Peter was put in that particular pressure situation, Peter would deny Jesus.

So there it’s Jesus, knowing enough about the character of Peter to be able to say ahead of time that, yes, Peter, you will deny me. Now, where this touches base with our class and prophecy and prophets is their understanding of a word, naham, which should be in your notes. I think I have both the Hebrew and the transliteration. Sometimes translated, repent, God repents, or God changes his mind. This word is used in Genesis 6:6. Sometimes translated, God was grieved. God was sorry that he had made man.

6 And the Lord regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart. (Genesis 6:6, ESV)

See, God regrets prior decisions that he has made. Since God did not know with absolute certainty that humanity would become so wicked. And so in Genesis 6:6, God is grieved. He’s sorry that he has made man events happen that take God by surprise. In fact, Sanders says the first sin of Adam and Eve was implausible and totally unexpected by God. Now, this doesn’t take away God’s wisdom from their perspective, but it only shows us a God who is willing to take risks. Several passages of scripture that they will appeal to, Jeremiah 19:5.

Shock is expressed over Israel’s behavior. God says, they did things that I did not command. They did things which never entered my mind. Jeremiah 18:7-10 is a key passage. We may come back and read verses seven through ten in a few moments, but it’s the passage about the potter making the clay. And God says in that passage that if he pronounces judgment and a nation repents, that he will not bring that judgment. If he pronounces blessing and a nation turns away from God and does evil, then God will not bring that blessing.

You see, God changes his mind in response to the actions and reactions of people, so that God’s mind, they would say, is not permanently or eternally fixed related to some things. So God confronts the unexpected. He experiences frustrations. He is willing to take risks because free agents choose unlikely courses of action. So in a nutshell, that’s open theism.

Now, this was sort of a hot topic several years ago. Evangelical Theological Society had a trial related to a couple of the proponents of open theism. I’m not sure if it’s kind of waned a little bit, at least in my perception. A brief response to open theism, and we’re going to be brief. I’ve given you some bibliography here in your notes.

Bruce Ware’s book, God’s Lesser Glory, is excellent. John Frame’s book, No Other God. I’ve given you an abstract, if you will, of Frame’s book. He’s very good in pointing out how they argue in an emotionally laden rhetorical way to sort of set up false dichotomies between their view and the traditional view. And Frame is good analysis.

There’s a whole issue of jets for the evangelical theological society that’s devoted to open theism. If you’re interested, you could take a look at that. Open theism is different from classic Arminianism. Classic Arminianism says God knows the future exhaustively. He has not foreordained the future or predestined the future, but he knows it exhaustively. Open theism says God does not know the future, the future actions of free individuals. Now, this term, Naham, is very important. Sometimes translated, relent, God relents from something to show you the slippery nature of Naham.

In 1 Samuel 15, this verb is used twice: in verse 11 and in verse 29. In one of those verses, it says, “God does not naham.” In the other verse, it says, “God does naham.” Same chapter, God doesn’t and God does. So, the slippery nature of this term, what is at the heart of this term? In some passages, God does not relent. God does not naham when he takes an oath. And this oath is in line with his eternal decree. Psalm 110:4. That’s the way this term is used.

And first, Samuel 15:29, God does not naham, he does not change. In Psalm 110, there’s an oath there. There are certain things that are certain that God does not change. It’s in line with his eternal decree. However, God does respond to the human situation. Genesis 6:6, 1 Samuel 15:11. Naham is used there before God does something significant. In Genesis 6:6, God recognizes the sinfulness of humanity. It didn’t take him by surprise, but he’s grieved over it and he’s getting ready to do something about it.

And naham is used there, and it’s also used in 1 Samuel 15:11, related to Saul. God recognizes the tragedy of Saul’s kingship, and he’s going to do something about it. From a human perspective, in Genesis 6:6, 1 Samuel 15:11, it may appear that God is changing his course of action. And from a human perspective, there may be a change of a course of action, but this is just a further outworking of his eternal decrees. You see, the problem we have in trying to understand God is God is both above time, transcendent.

He sees the end from the beginning; he’s decreed the end from the beginning. But God also enters into time. He enters into the temporal world that we experience.

10 declaring the end from the beginning and from ancient times things not yet done, saying, ‘My counsel shall stand, and I will accomplish all my purpose,’ (Isaiah 46:10, ESV)

And the difficulty we have as finite human beings is to try to understand God from both of these perspectives. And sometimes what we see is a limited human perspective. And it may look like God is changing a course of action, but it’s all according to his eternal decree. I have a quote in your notes from Block, and I’ve got the bibliography there for it. It’s worth reading.

Might God, rather than being open about options in the future, be using the language of relationship to highlight his engagement with us while still foreknowing precisely how these relationships will proceed? Should we not see God’s changes as grounded in a divine character that has knowledge of what our responses will be, but still has to communicate a reaction in time and space that touches not only our mind but our heart?

Jeremiah 19:5: God says, it never entered my mind. And what’s focused there is the child sacrifice, burning their sons in the fire.

5 and have built the high places of Baal to burn their sons in the fire as burnt offerings to Baal, which I did not command or decree, nor did it come into my mind— (Jeremiah 19:5, ESV)

Now, God had already warned Israel about this abomination in Deuteronomy 12:31, so apparently, it had entered into His mind at one point, since He warned them not to do this.

31 You shall not worship the Lord your God in that way, for every abominable thing that the Lord hates they have done for their gods, for they even burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods. (Deuteronomy 12:31, ESV)

So, either Jeremiah 19:5 is saying, this was not my purpose for them, or God is expressing His extreme disapproval of this vile activity, so vile He doesn’t even want to consider it. It’s sort of like those passages: God came down to look at the Tower of Babel; God called out to Adam and Eve, “Adam, where are you?”

9 But the Lord God called to the man and said to him, “Where are you?” (Genesis 3:9, ESV)

Well, that wasn’t because God didn’t know where Adam was, which is sort of the direction open theism goes, but it was to call forth a response. Plus, there are scriptures that affirm God’s knowledge of the future is exhaustive. And God’s knowledge of the future includes the free acts of individuals we’re going to see over. In Isaiah 40:48, there are several passages that demonstrate God’s knowledge of the future. He knows the end from the beginning, and it’s what sets him apart from the idols.

We’ll take a look at those passages when we get over there. But God even calls Cyrus by name ahead of time. Imagine how many actions of free individuals must be involved or coordinated for Cyrus to be born in a certain place to be named Cyrus. God knows the future. God knows and has foreordained the free actions of individuals. Peter’s denial. Did Jesus know from Peter’s character that he would deny him three times? You might be able to argue that Jesus knew from Peter’s character that he would deny him.

But how could you know three times, which is what Jesus told Peter, Psalm 139:4. Even before there is a word on my tongue, you know it. Before I speak the next word, God knows it. That’s pretty specific.

Now, there’s a debate, obviously, and we can’t get into this. You know, how do you put together God’s predestination with human responsibility? I like Acts 2:23, where Peter says to the men of Israel, he’s speaking,

23 this Jesus, delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men. (Acts 2:23, ESV)

He says, “this Jesus delivered up according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God.” That’s predestination. “You crucified and killed by the hands of lawless men.” That’s human responsibility. Both of them are there. And God can hold us responsible because we do act freely according to our nature. Now, we don’t have the ability to choose a, b, or c. We have the ability to choose according to our nature. And when we sin, we want to sin. Our wills are involved in that sin. We choose to do it. We are involved in it, we want it.

And that’s how God can hold us responsible, even though he has foreordained everything that has come to pass. We’re not robots. We actively participate with our wills. We desire and want and commit sin. So it is a mystery, and we can’t get into all the ins and outs of this.

But at least we wanted to sort of address, I think, this misunderstanding of prophecy, because it does relate to this key term in the Old Testament, this term naham, and it is related to prophecy, as we will continue to see. Comments or questions before we move on?

Well, you know, among groups that are rooted in reformed theology, the Westminster Confession of Faith, it’s not having much of an impact. Several years ago, there were students from more independent Baptistic churches that were talking about how much they were running into it.

But beyond that, I’m not real sure. Certainly there are some of the evangelical groups associated with evangelical theological society that struggle with it, but it may not be something that you run into much. Yes, sir. Is this system constructed to preserve their notion of free will? Basically, that’s part of it. They’re also driven by suffering in the problem of evil. So to keep God from that problem, that’s part of it.

In fact, they highlight situations of suffering, and then they’ll say, how can you believe in a God that has foreordained this as part of their argument. All right, well, let’s move on and talk about prophetic fulfillment and historical contingencies. This relates partly, well, directly to the article that you had to read by Pratt, but it also sort of addresses indirectly some of the things we just looked at. The heart of prophecy is not prediction. Now, prediction is a part of prophecy. We don’t want to deny that.

But the heart of prophecy is proclamation, not just foretelling, foretelling, but forth telling. Forth telling is sort of one way to put it. And Pratt’s article puts this whole notion of historical contingencies in the context of the Westminster Confession of Faith and the statement in there on Providence. I think I’ve given to you a part of that statement in your notes: the decree of God comes to pass immutably according to the nature of secondary causes.

By the way, in Boyd’s original book, there’s not a word about secondary causes, has no interaction with that. But the decree of God comes to pass immutably according to the nature of secondary causes, either necessarily, freely, or contingently. Necessarily. One event may cause another because of regular patterns of nature. Freely, events that appear random from a human point of view, they appear random. It doesn’t mean they are, but they may appear to be random and then contingently. God’s interaction with volitional creatures, and that’s what we are going to focus on.

In other words, a prophecy may be given, and the fulfillment of that prophecy may be dependent to a certain degree on the interaction, human interaction to that prophecy. That’s the historical contingencies. There are historical contingencies that may affect a prophecy that is given. I’ve given some examples in your notes. There is an example of the removal of judgment, and the example comes from 2 Chronicles 12:5-8, related to Rehoboam. Verse five says, this is what the Lord says, you have abandoned me, therefore I now abandon you to Shyshak, pharaoh of Egypt.

God tells Rehoboam, “you’ve abandoned me. I’m abandoning you. I’m giving you over to Shyshak.” Judgment, destruction. Rehoboam repents. And so, verse seven, God says, “Since they humble themselves, I will not destroy them.” A prayer of repentance had an effect on this proclamation from God. So there was in this instant a removal of judgment. There’s also examples of delay of judgment. 1 Kings 21 is an example of delay of judgment. God says to King Ahab, and this is in the context of Naboth’s vineyard.

And you know, the wickedness of King Ahab and Jezebel, not just generally, but specifically in relationship to Naboth’s vineyard. “Verse 21, I will bring disaster upon you, Ahab.” And it goes on to talk about cutting off every male from the house of Ahab as a part of God’s judgment against Ahab and his household. What’s Ahab’s response? One of the few times he ever responds this way, he humbles himself. He repents.

For in light of hearing this statement and 1 Kings 21:29, God says, “because he has humbled himself before me, I will not bring disaster in his days.”

29 “Have you seen how Ahab has humbled himself before me? Because he has humbled himself before me, I will not bring the disaster in his days; but in his son’s days I will bring the disaster upon his house.” (1 Kings 21:29, ESV)

Disaster is still going to come, and the males from the house of Ahab are still going to be cut off. But God says, “I’ll delay that because of his response of humbleness and repentance.” How Ahab responds affects this prophecy. Jeremiah 18 is a key text, and why don’t you just turn over to Jeremiah 18? We’ll read a portion of this in this passage.

In Jeremiah 18, God is the potter, and as a potter can do with the clay whatever he desires, whatever he wishes, God can do with his people as he sees fit. And then it talks about the way God operates and interacts with nations, kingdoms, and his people.

7 If at any time I declare concerning a nation or a kingdom, that I will pluck up and break down and destroy it, 8 and if that nation, concerning which I have spoken, turns from its evil, I will relent of the disaster that I intended to do to it. 9 And if at any time I declare concerning a nation or a kingdom that I will build and plant it, 10 and if it does evil in my sight, not listening to my voice, then I will relent of the good that I had intended to do to it. (Jeremiah 18:7-10, ESV)

Verse seven: if at any time I declare concerning a nation or a kingdom, that I will pluck up and break down and destroy it, that would be the judgment side. If that nation concerning which I have spoken turns from its evil, I will relent, that’s our key term, of the disaster that I intended to do to it.

And if at any time I declare concerning a nation or kingdom that I will build and plant it, that’s the salvation side. Both of these tearing down and building go back to the call of Jeremiah. So God says, if a nation or kingdom, I declare, I will build it and plant it. Verse ten, if it does evil in my sight, not listening to my voice, then I will relent. Our key term of the good that I intended to do to it.

God says intervening historical contingencies related to how people respond can affect the fulfillment of an announcement of judgment or salvation. And when God says in these verses, as he does in verse eight, that I will relent of the disaster that I intended to do to it, he’s not talking here about his eternal decree. He’s talking here about his providential declaration of intent. And that providential declaration of intent can be adjusted. We don’t always know what God’s eternal decree is. Secret things belong to the Lord our God.

29 “The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law. (Deuteronomy 29:29, ESV)

Now, sometimes we get an insight into that in some predictions or prophecies, but we’re not always dealing at that level. We’re dealing at the level of God’s providential declarations of what he may or may not do. And I think that’s what’s going on here. In Jeremiah 18, there are connected with prophecies. Who knows? Questions. Who knows? Maybe God will be gracious. And a great example of that, and I think I’ve given this example to you in your notes, is 2 Samuel 12, the child born to David and Bathsheba.

God declares in verse 14 through Nathan the prophet,

14 Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the Lord , the child who is born to you shall die.” (2 Samuel 12:14, ESV)

God’s declaration. So what does David do? Does he resign himself to the death of the child at the end of this incident? In verse 22, David says,

22 He said, “While the child was still alive, I fasted and wept, for I said, ‘Who knows whether the Lord will be gracious to me, that the child may live?’ (2 Samuel 12:22, ESV)

There was a statement through Nathan the prophet, the child will die. David says, I prayed, I pleaded. I hoped that God would be merciful in this particular situation.

Now, in this situation, the child died. We’re going to look at an example several minutes from Jonah. You could also see Joel 2:14, who knows? Judgment has been declared, but maybe God will be gracious. That’s the understanding within the Old Testament context. Prophecies, statements, declarations from God can be adjusted through repentance. The purpose of such prophecies is to motivate God’s people to respond in an appropriate way. The purpose of these prophecies is that God’s people would repent when these declarations of God’s intent are declared. So a prophecy may be given. There may be historical contingencies.

That prophecy and how it works itself out in history may be dependent upon the responsive people. That’s what we mean by historical contingencies. Now, this leads us to prophetic levels of divine determination. In other words, a prophecy does not always have to be an absolute statement. And so, let’s go through there’s four of these. There are, in the Bible, conditional predictions, where people’s choices and how they respond are secondary causes used by God in the outworking of his purposes. So, there are prophecies where the conditions are clearly stated.

And there are two options given, bipolar and unipolar. It has nothing to do with psychiatry; it’s just the terminology that they use. A bipolar prediction lays out both the negative and the positive. Isaiah 1:19-20 is an example. If you are willing and obedient, you will eat of the good of the land. That would be the salvation or the positive part.

19 If you are willing and obedient, you shall eat the good of the land; 20 but if you refuse and rebel, you shall be eaten by the sword; for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.” (Isaiah 1:19-20, ESV)

If you refuse and rebel, you will be devoured by the sword. That would be the negative or the judgment part. Both of those are presented, both negative and positive, both judgment and salvation options.

Sometimes only one of those options is presented, called unipolar Isaiah 7:9. The negative side is presented. If you are not faithful, King Ahaz, you will not stand at all. And the implication is, if you are faithful, you will stand. But only one side is presented. Jeremiah 7:5-7 has the positive side. If you will mend your ways, then I will cause you to dwell in this place. If you will respond appropriately, then you will dwell in this place.

And the implication is, if you don’t respond appropriately, you won’t dwell in this place, but only one. One side is explicitly stated. That’s one level or one type of prediction. There are also unqualified predictions, and here the conditions are not explicitly stated, but they are implied conditions. Implied conditions, not explicit conditions, but implied conditions. And this is where Jonah 3:4 is a great example. What does Jonah proclaim to the city of Nineveh? 40 days and Nineveh will be destroyed. Now, did that happen? Was Nineveh destroyed?

As we get to the book of Jonah, we’ll see it wasn’t destroyed. Why was not the city of Nineveh destroyed? That’s what Jonah proclaimed, right? Well, the people repented. The king, the city repented. And here you have one of those statements: Who knows? Maybe God will not bring this disaster upon us. There is an implied condition. Jonah is not a false prophet because the city is not destroyed. It’s understood that the condition here is an implied condition, not explicitly stated. So you have statements by the prophets that may contain implied conditions.

Another category, confirmed predictions, either confirmed by words like in Amos chapters one and two, where God says, “I will not turn back,” or confirmed by signs, as in Isaiah 7:14, a sign is given there, and we will talk about that when we get to Isaiah seven. These predictions show a higher level of divine determination to carry them out. And then finally, you have predictions that are connected to an oath that God takes. God swears an oath, like in Amos 4:2. It says, the sovereign lord has sworn by his holiness.

When God takes an oath, your level of certainty goes up. Ezekiel 5:11, “As I live, saith the Lord.” These predictions are pretty much inevitable because they are in line much more with the divine decree. And yet, there still may be some latitude in how they are fulfilled: the timing, who will experience the predicted prophecy, how the means, in other words, the means through which it will come about. To what degree? Sometimes these still can be affected.

So I think it’s helpful when you read prophecies in the Old Testament to understand this nature of the character of prophecy. Not every statement should be seen as an absolute, concrete statement, but many times it’s just proclamations of God’s providential declaration of what he intends to do and how people respond can be very significant in the outworking of God’s eternal purposes. Now I have a final section here, historical contingencies and the test of a true prophet.

And Deuteronomy 18:22 says, if the word of a prophet does not come to pass or come true, then that’s a word that the Lord has not spoken, and that prophet is classified as a false prophet.

22 when a prophet speaks in the name of the Lord , if the word does not come to pass or come true, that is a word that the Lord has not spoken; the prophet has spoken it presumptuously. You need not be afraid of him. (Deuteronomy 18:22, ESV)

Well, this has to be understood in light of how the prophets intended their predictions to be taken, and God’s people understood how this worked, as is evidenced from David’s response in 2 Samuel 12. There was an understanding by God’s people that repentance, a humbling before God, might be very significant in terms of the outworking of a particular declaration of God’s intent. Pratt’s article that I have you read either in the book or in his third mill, I think his third mill.org, deals with these things.

And it’s very helpful when you read the prophets to have this perspective, because sometimes you read an article that says, well, God said this about Tyre, and it never was fulfilled in history this way; that must mean that it’s false. Well, this historical contingency thing impacts those kinds of issues. Comments or questions on this before we actually, before we take a break? Yes, sir. In using that sort of rationale, that prophecy must come true in order for the prophet to be shown true with other religions and apologetic situations.

Do other religions say Mormonism takes this approach, or? My sense is, and I’m, you know, I don’t know Mormonism in depth. I don’t know other religions related to this. My sense is they don’t, because I think most evangelicals don’t take this approach. I mean, I think this is an extremely helpful thing that Doctor Pratt has presented for us. And I think if you begin to look at scripture, you can see it there and the outworking of it. So my sense is that they probably do not take this approach.

Now, this is not to say that we have abandoned the whole idea of prediction. I mean, Isaiah 7:14 will be a very important passage in that regard, and we’ll talk about that when we get there. I sort of see that as a direct prediction of the messiah, and we’ll talk about why when we get there. So we’re not trying to abandon the fact that sometimes there are absolute statements that do, that are fulfilled, but not every prophecy would sort of fit that category. Anything else?

All right, let’s take a break and then we’ll come back and pick up where we have left off. This audio lecture is brought to you by RTS on iTunesu at the virtual campus of Reformed Theological Seminary. To listen to other lectures and to access additional resources, please visit us at itunes rts.edu. For additional information on how to take distance education courses for credit towards a fully accredited Master of Arts in Religion degree, please visit our website at virtual rts.edu.

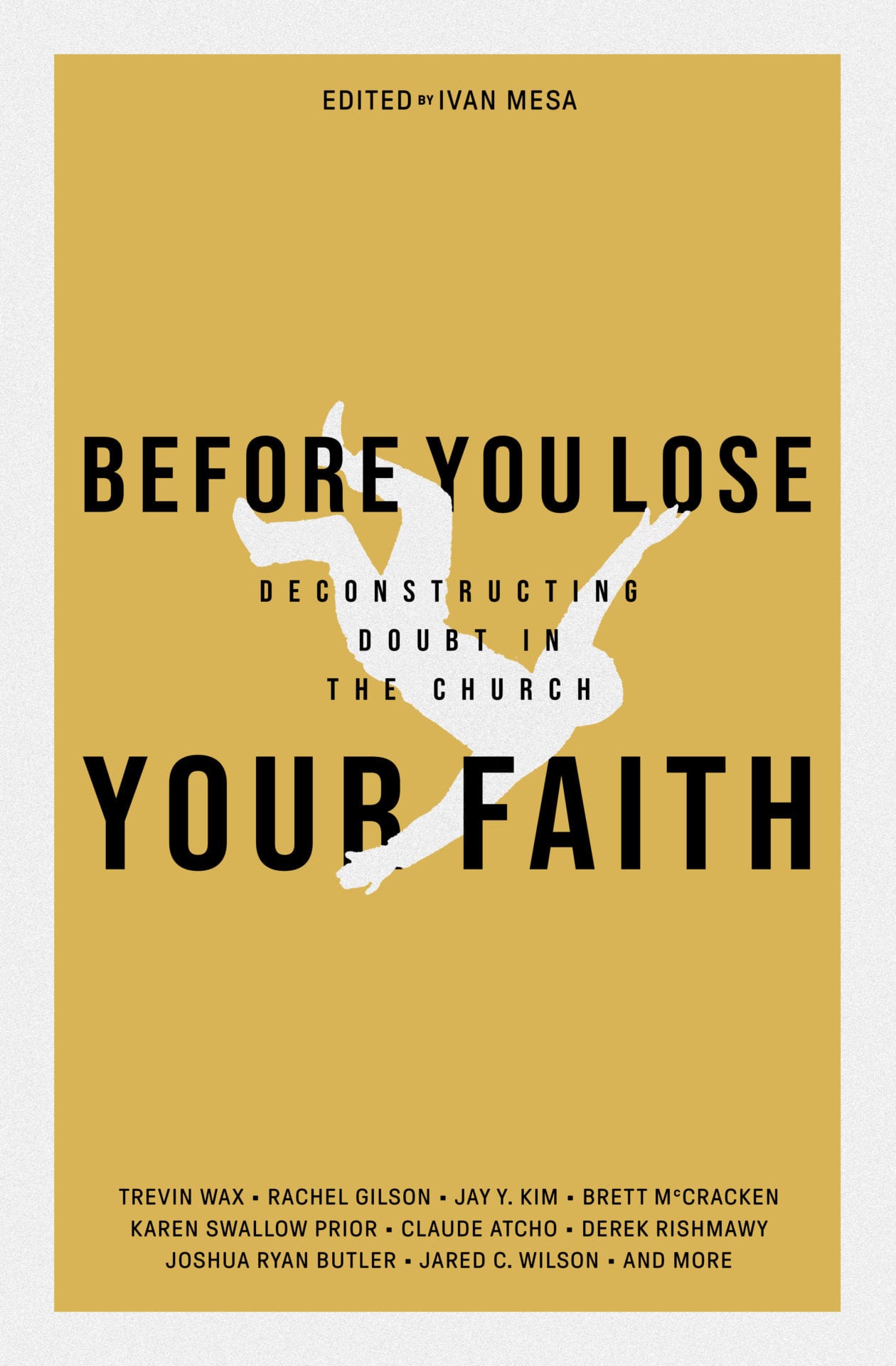

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!