A quick glance through Owen Strachan’s blog reveals many things that concern him about the rising generation of evangelical Christians. His latest book, The Colson Way: Loving Your Neighbor and Living with Faith in a Hostile World, primarily counters the prevailing skepticism he sees among millennial Christians. Strachan, associate professor of Christian theology at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, wants to show these millennials you can faithfully proclaim the gospel and orthodox Christianity while simultaneously loving others and effectively engaging the public square. And so he wrote a book about Charles “Chuck” Colson—a man from a previous generation who did just that.

My first extended conversation with Chuck was in the spring of 2010. My wife and I visited his home in Naples, Florida, to discuss the prospect of my joining the Chuck Colson Center for Christian Worldview. The Colson Center was the focus of many of his later-life initiatives such as BreakPoint radio, the Centurions Program (a one-year worldview training program), and Doing the Right Thing (a joint video teaching series with Brit Hume, not Spike Lee). I was strongly considering doctoral studies but told him that, if given the opportunity, I’d consider it far better to work alongside him for a few years. “You’re right!” he said, and yet it didn’t sound arrogant at all. For Chuck, it was always about the mission of defending and declaring the Christian worldview in the public square, and not really about him. I took the opportunity and have never regretted it.

Waking a Generation

The Colson Way identifies the Chuck Colson I knew but struggle to describe: profoundly gifted, furiously driven, courageous, intelligent, and yet remarkably teachable. His mind never stopped working, and he never stopped believing that the God who had redeemed his life would also use his life to help others. His long list of accomplishments, which Strachan details, will leave a new generation asking, “How did I not know about this guy before?” It left me wishing I’d been able to work longer with him.

Still, to be clear, The Colson Way is as much a gauntlet thrown down as it is a biography. As Strachan puts it, “I want this book to wake up a generation.” And so at the end of each chapter, after telling the next part of Chuck’s story, he offers specific applications and issues specific challenges to the readers he wishes to awaken.

Challenging the Church

Chuck believed the lion’s share of his calling was to stir up the church. After his release from prison, he famously worked to move the church to bring the gospel to those in prison. An avid student of theology and worldview, he wanted the church to understand how a Christian vision of life and the world offered better solutions to cultural problems than did secularism, a vision he then applied—with impressive results—to criminal justice reform. Along the way he proclaimed to the church how moral breakdown was creating cultural chaos, including (but not limited to) the dramatic increase of America’s prison population. Near the end of his life, Chuck presciently warned that the cultural assault on traditional sexual morality and marriage in America would mean less and less space in the public square for true freedom of conscience.

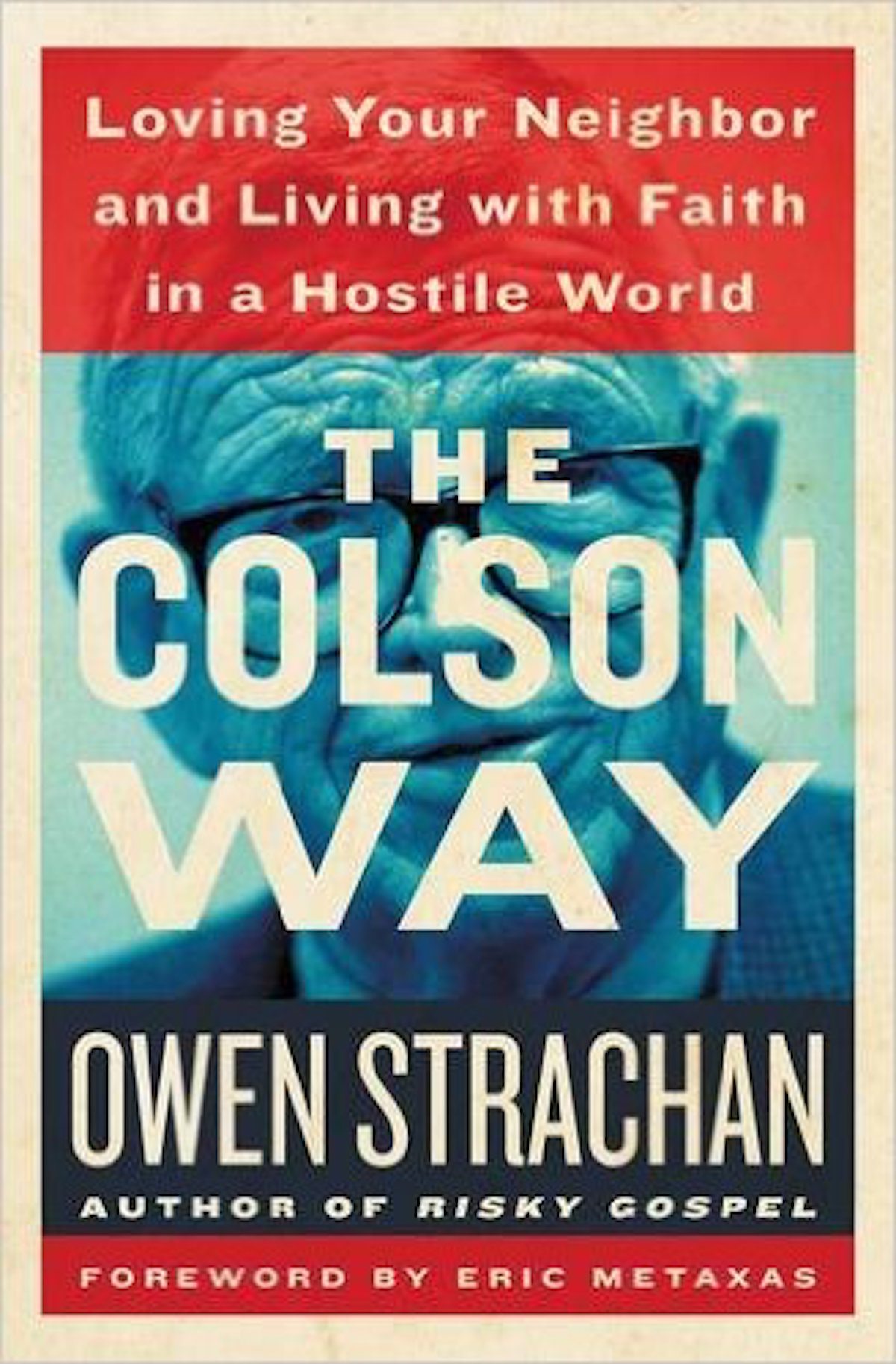

The Colson Way: Loving Your Neighbor and Living with Faith in a Hostile World

Owen Strachan

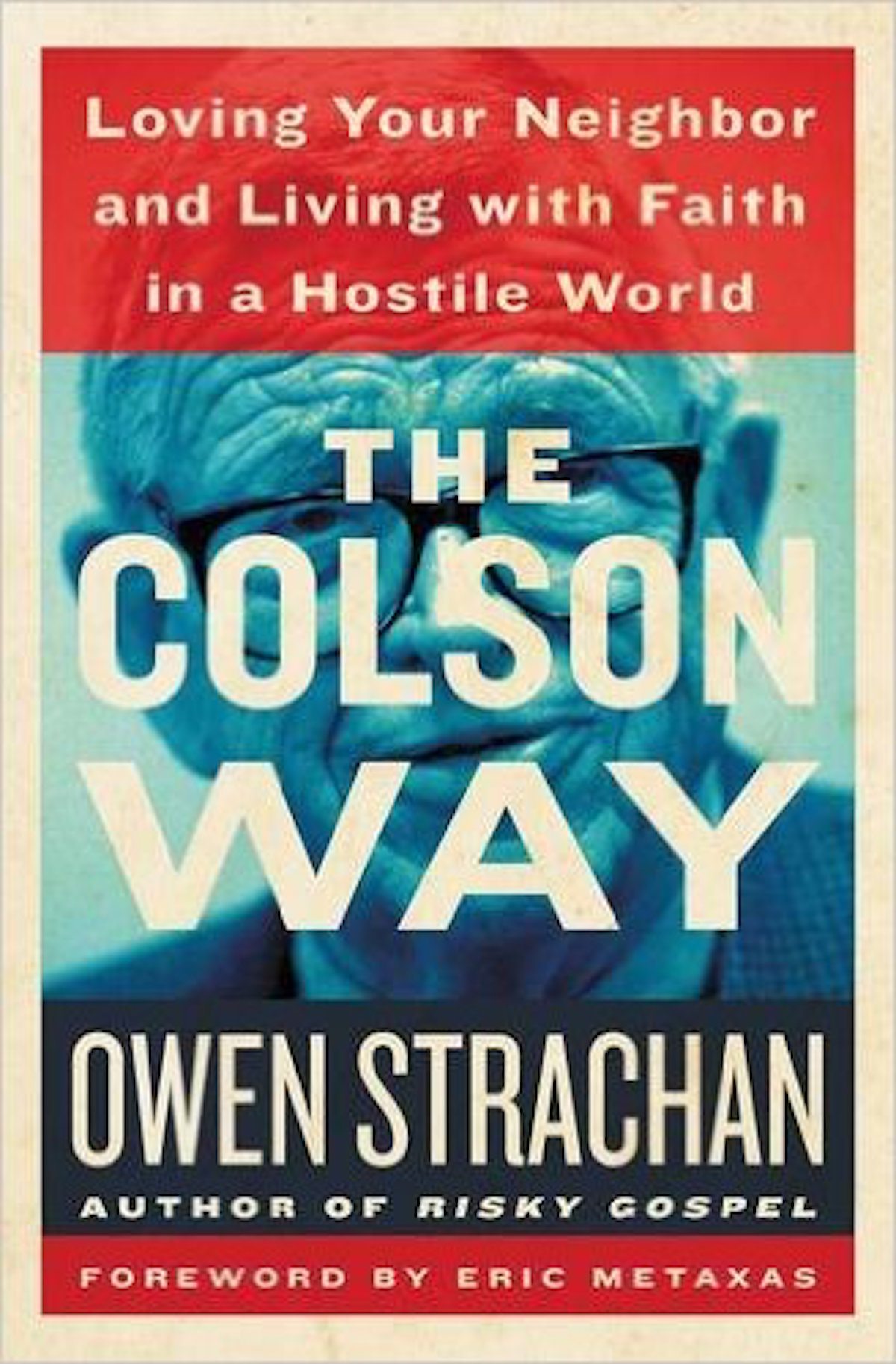

The Colson Way: Loving Your Neighbor and Living with Faith in a Hostile World

Owen Strachan

The Colson that Strachan describes wasn’t just a man of words. He lived a life of word and deed, conviction and courage, faith and action. As Robert George told me soon after Chuck’s death, Chuck easily could’ve been an academic, and the organizations he created—Prison Fellowship and the Colson Center—could’ve been think tanks. But Chuck wouldn’t have it. He created them to be “do tanks” as much as anything.

The same is true of Evangelicals and Catholics Together (ECT), probably the most controversial of Chuck’s initiatives, which he co-founded with his close friend Father Richard John Neuhaus. In a too short description of ECT, Strachan talks of the value of co-belligerence with allies also committed “to support the permanent things.” ECT was one among many of Chuck’s initiatives to find comrades across convictional, political, creedal, and other lines. ECT supporters would argue it’s one that has perhaps borne the most cultural fruit in light of the emerging challenges to life, marriage, and religious liberty. ECT critics, on the other hand, would say the good accomplished on social issues is overshadowed by theological confusion. I wish Strachan had dealt with the issue in greater depth.

Energizing Book for a Fractured Age

Overall I found Strachan’s creative and well-written book to be accurate, inspiring, and, most of all, energizing. I pray it will move the next generation of Christians to fearlessly put their faith on the line and into action. I desire what Strachan does:

I want Colson to catalyze you to live with bold faith in a fractured age. Whether you counsel a young woman who feels abortion is the only way out of her personal nightmare, raise support to stop the sex trafficking of women in your country, or tell a classmate about the liberating gospel of Jesus, I want you to be like Colson and to be ready, as an ancient sage once said, to speak—but not only this. Like Colson, I want you to be ready to put steel in your words by acting courageously on them. (xxvi)

May it be so!