About six months ago, a pastor in Kenya told his congregation that they could be saved by good works.

In his pews were about 80 children from a nearby orphanage, ranging from second grade to high school.

“The kids came home visibly upset,” said David Pederson, who runs the Christian compound where the orphanage is housed, along with a Christian classical school and a teachers’ college, housing for missionaries, and a farm. “They were really distraught: ‘This isn’t what the Bible teaches. This isn’t right.’”

“They were debating and asking questions,” said David’s wife, Julie, who co-administrates the campus with him. “It was really good.” Within a week or two, most of them switched to other churches.

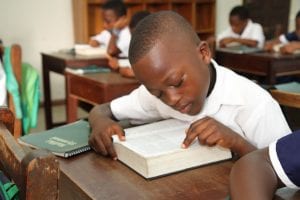

The children had just finished 30 weeks in a daily Bible study on the book of Romans, so they knew grace backward and forward. But the timing wasn’t just an unlucky coincidence for the pastor—these children are in the middle of a 553-week Bible study. That’s more than 10 years of memory verses and study questions.

“By the time they get to grade 12, they will have studied 90 percent of the Bible verse-by-verse,” David said.

The curriculum was written by Reformed theologians and is used—partially or completely—in orphanages, church schools, widows’ groups, and partner churches in Africa. Thousands of students, teachers, employees, church leaders, and church members have studied the Bible with it.

A Bible study this intense “doesn’t exist anywhere else—even in the United States,” David said.

Until now. This month, the Rafiki Bible Study for Groups is being released for use in America.

It’s like a homecoming, because the Bible study came from the United States, the brainchild of American missionary Rosemary Jensen.

“I’m a Bible person,” she told TGC. “I’ve loved the Word of God since I was a teenager.”

“If she were made a doctor of the church, I think she would merit the title Doctor Indomitabilis—such is her fierce determination to ‘observe all’ that Jesus has commanded, and to help, encourage, and—if need be—cajole others into making that possible for as many people as she can possibly reach with God’s Word,” Reformed Theological Seminary professor Sinclair Ferguson told TGC. “Now in her ‘golden years,’ Rosemary still makes you feel that her heart to press on to know and serve the Lord is bigger than her whole body!”

Jensen’s definitely in her golden years—this July, she’ll turn 90. But that’s not likely to slow her down. When she first dreamed up the Bible study project, she was a 75-year-old retiree.

Missions to Africa

Jensen grew up Reformed, in a Southern Presbyterian church in Jacksonville, Florida. She came to faith in Christ when she was 16.

“I knew the only way you can know God is through the Bible, so I decided I was going to read one chapter every day,” she told TGC. “I got through Genesis okay and Exodus okay. By the time I got into Deuteronomy, I was thinking, ‘Oh my goodness.’”

But she was determined, and for three and a half years, she read a chapter of her King James Version every day.

“You know what happens to you after three and a half years of doing something?” she said. “You develop a habit. I was in the habit of reading the Bible. I couldn’t stop. I didn’t want to stop. And I will tell you for the rest of my life—I’m 89 now—I have read the Bible every day that I can remember.”

For the rest of my life—I’m 89 now—I have read the Bible every day that I can remember.

When she was 17, she heard a foreign missionary presentation at her church and fell hard for the idea. But back then, “women could only be missionary nurses or teachers,” so she went to college, majored in education, and began teaching school in Florida.

When she was 23, her sister told her the army was offering to train young women in occupational therapy. Jensen “liked arts and crafts” and her day job “was not very exciting,” so she joined the Army. While there she met an Army battalion and regimental surgeon just back from Korea.

“He was a major at that time, and he ordered me to marry him, so I said, ‘Yes, sir.’” She’s probably said that line a hundred times, but it still makes her laugh. (Bob Jensen passed away in 2014.)

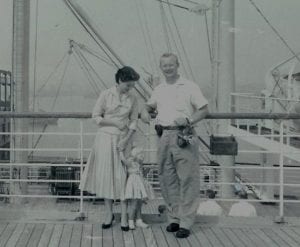

They both wanted to go to the mission field—him back to Korea, her to Africa. “By the grace of God, we went to Africa,” she said, laughing again. “I just loved Africa.”

The Jensens took their 2-year-old daughter and worked in Tanzania from 1957 to 1966. Bob helped to start Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center, a regional hospital that is still the largest in the area. Rosemary taught at an international school and gave birth to two more daughters in a local mud brick hospital. And they both watched 34 African countries declare independence from Western Europe.

Those new governments started off shaky, as politicians sorted out power and responsibilities. Everyone was looking for support, and with their hospital connections and American passports, the Jensens were good friends to have. The couple “recognized the importance of working with African government and church leaders,” said Karen Elliott, who leads the foundation the Jensens’ started. Over the years, they built friendships with leaders across the continent.

“The grace of God puts us in the place he wants us to be, because he knows what he wants us to do,” Jensen said. Years later, her work would benefit from those decades-long friendships.

Bible Study Fellowship

The Jensens came back from Africa in 1966, eventually settling in San Antonio where Bob was chief of medicine at San Antonio State Chest Hospital and Rosemary started a Bible study in her home. One of her attendees connected her with Bible Study Fellowship (BSF)—a structured, expository study of the Bible developed by missionary Audrey Wetherell Johnson in 1959.

“I was intrigued by her,” said Jensen. It was hard not to be. Johnson was also a former missionary, having spent 17 years in China—including two and a half years in a Japanese internment camp during World War II and another 18 months under house arrest before deportation by the communists. “I was also intrigued by the whole study because it was in-depth, it was good, it was strong, and it was demanding of people to study.”

Within two years, Jensen was a BSF area adviser; within seven years, she was running the whole operation. She spent nearly 20 years as executive director; under her watch, around 200 BSF classes grew to more than 900.

“In the meantime, I got to know a lot of people,” Jensen said. She’s not kidding. She and Bob were part of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy and two of the 334 signers of the Chicago Statement. As head of BSF, she was invited to join the council of the Alliance of Confessing Evangelicals, which over the years included Mark Dever, Ligon Duncan, Michael Horton, Al Mohler, and R. C. Sproul.

“But I’m not a theologian,” she told Presbyterian pastor James Montgomery Boice, who asked her to join.

“No, you’re not,” she remembers him saying. “We’re writing about it, but Rosemary, you’re doing it.”

Doing Theology

“My goal was to put BSF classes in Africa, because I was involved in those countries,” Jensen said. She and Bob had lived on his income while saving hers, which enabled them able to start the Rafiki Foundation. (Rafiki means “friend” in Swahili.) They started with two missionary couples who worked at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center during the day and taught BSF classes at night.

For 15 years, Jensen grew both BSF and Rafiki. She sent more vocational missionaries, and they started more BSF studies—40 in Africa and more around the world.

When Jensen was 70, she retired from BSF so she could focus on Rafiki. (Jensen is “an entrepreneur extraordinaire,” former Gordon-Conwell Seminary professor David Wells said. “She’s always looking for the project that needs to be done. She could’ve been the president of a Fortune 500 company.”)

As a retirement gift, BSF gave Jensen seed money for an orphanage in Uganda. Immediately, she started looking for land in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Ghana.

Within five years, Rafiki had at least 50 acres in each of 10 countries. More than half was given by church officials, government leaders, or tribal chiefs. “That was a result of the Jensens living out their commitment to be a friend—rafiki—to Africans since the ’60s,” Elliott said.

Jensen “came to Uganda to inform me about her desire to start a Rafiki establishment, which gives hope and education to young people who are in difficult circumstances,” said Ugandan First Lady and minister of education Janet Museveni. “I welcomed her to Uganda. . . . We share our love for the Lord, and it keeps us united.”

Jensen has “always wanted to give Africa the best,” Elliott said. Instead of rows of mats on the floor in a single large building, Rafiki put orphans on beds in small cottages, with running water, electricity, and house “mamas.” When nearby government schools turned out to be overcrowded and poorly run, Jensen built her own schools, using classical curriculum. When quality teachers were in short supply, Jensen added teachers’ colleges to each campus.

“Africa always seems to get the leftovers,” Elliott said. “It’s great to be part of something where the buildings are beautiful, the landscaping matters, and the curriculum is high quality. It’s the things you’d do for your own children.”

But about five years in, Rafiki was feeling feel the loss of the BSF materials.

“I remember the conversation with the Rafiki board about what we could do to ensure our orphans and their ‘mamas’ would always have their minds in the Bible,” said Wells, who was then a board member. “Someone said, ‘Well, why don’t we do something like BSF has done?’”

At that time, BSF had a daily exegetical Bible study created for around 20 books of the Bible.

“Yes,” Jensen said immediately. “Except we’ll do the whole Bible.”

“Mercifully, I didn’t open my mouth,” Wells said. “But I was doing this mercenary calculation. I thought, ‘Okay, you’ve got 66 books of the Bible. How many hours will it take? How many kids do we have?’”

High-Quality Bible Study

It took more than 10 years.

Jensen used her connections to corral Reformed pastors and professors to write the studies—Bob Godfrey. Rick Phillips. Palmer Robertson. Dennis Johnson. Guy Waters. (She can be very persuasive. Her staff riff on the Campus Crusade line: “God loves you, and Rosemary has a wonderful plan for your life.”)

Then “she started sending lessons to me, saying, ‘Would you please vet these?’” Wells remembers. “I sort of informally became the editor of the whole thing.”

He was a good choice. Wells grew up in Zimbabwe, and he and Jensen had the same vision: Since Africa does not have a plethora of Bible commentaries and resources, they’d have a little commentary on each book. It would be written for adults, then geared down for the children. The theology would be Reformed. And the context—the illustrations and examples and references—would be African.

“I edited every one carefully,” Wells said. Two years in, he retired from the seminary, but kept his office. He went back in every day, writing a book and editing the Rafiki Bible study.

“I couldn’t even guess how many hours it took,” he said. “We couldn’t accept some, and that’s why I ended up writing five of them. But we were determined to have a consistent Reformed vision and quality without overriding the personality of the writer or the book they were commenting on.”

The lesson on John 1:1–18 starts by listing the doctrinal focus, which includes the deity of Christ, the personhood of the Trinity, and Christ as God’s revealer. Then follows four or five pages of commentary, to be read on Days 1 and 2 along with the text.

“Because he is God, Jesus reveals God,” wrote Rick Phillips, who is also a TGC Council member. “Moreover, Jesus possesses the power of God’s grace actually to enable sinners to believe. This is why John says, ‘we have seen his glory, glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth’ (John 1:14), and ‘the law was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Jesus Christ’ (John 1:17). Jesus not only provides us with information about God, but he grants grace, through faith, to know God and be saved.”

Days 3 through 7 list questions to consider, but they aren’t the painfully obvious Sunday school ones. An example: “Psalm 33:6 says, ‘By the word of the LORD the heavens were made.’ How did God’s Word create the heavens and the earth? When John describes Jesus as ‘the Word,’ what does this say about Jesus’s role in accomplishing God’s will? How did Jesus accomplish God’s will when he came to earth? Read Psalm 107:20. How does God’s Word not only bring creation but also salvation?”

The studies come in eight different versions—for Rafiki mamas, for national workers, and for multiple grade levels. (“What is the Trinity?” asks the 4th-to-6th-grade lesson. “What is the incarnation?”)

Each week includes a verse and a Westminster Shorter Catechism question and answer to memorize. (This lesson’s catechism: “What is forbidden in the first commandment?”)

More than 10 years and thousands of pages later, Jensen had her Bible study.

“It’s quite an amazing thing,” Wells said.

Giving it Away

“We don’t sell our Bible study,” Jensen said. “I don’t believe in selling the Bible.”

She rolled it out in the 10 Rafiki schools, which educate about 800 orphans and another 1,300 kids from the surrounding communities. At the same time, Rafiki employees and teachers’ college students and widows’ groups started using it. Then Jensen called up those old friends and established partnerships with 23 African denominations—which run about 20,000 schools. In the next decade, Rafiki expects to see at least 1,000 church schools adopt both Christian classical curriculum and also the Rafiki Bible study.

“Parents are bringing children to our schools and within a few months saying, ‘My child is a different child. What are you doing?’” Elliott said. “We’ve had young men and women who have maybe been churched but been taught a gospel of works or prosperity theology tell us, ‘Now I understand grace. I really do know the Lord now, and I’m secure in my salvation.’”

One of those students is Joy John, who grew up in the Rafiki village in Jos, Nigeria. She and her siblings were scattered among relatives before an aunt enrolled her.

“I have thought of how life would have gone with me if I had never been brought to Rafiki,” she told TGC. John is now 22 and studying accounting at Bingham University in Nigeria. “I would have never known God the way I do now. I would have been a regular Sunday churchgoer and never really know the essence of attending service. I thank God for the personal relationship Rafiki has helped me develop with Jesus.”

Still Going

“I remember when I first met Rosemary I was struck by her commitment to the Scriptures,” Cleveland-area pastor and TGC Council member Alistair Begg said. “Her enthusiasm for discovering what the passage means and then explaining why it matters was infectious—and that is presumably why so many caught the bug for sanctified biblical scholarship.”

She’s not done. Nearly 90 and in a senior living apartment, Jensen is still the active president of the Rafiki Foundation. Now that the Bible study is complete, she’s working on a new project—getting Bibles into the hands of African pastors, seminary students, teachers, and schoolchildren. In 2017 she started the Rosemary Jensen Bible Foundation; so far, she’s sent out more than 40,000 Bibles.

“Rosemary Jensen is one of the most driven people I know,” Westminster Seminary California professor Michael Horton said. “And in all of her leading roles as a humble servant, Scripture has been the common denominator. She knows it, reads it, cherishes it, follows it, and literally sends it all over the world and especially throughout Africa. The personal friend of presidents and first ladies all across the continent, she has exploited every relationship not for her own political ends but for one purpose—to teach and reach the nations with God’s Word.”