In an important essay that has sparked considerable conversation, Alan Jacobs raises a key question:

Half a century ago, such figures existed in America: serious Christian intellectuals who occupied a prominent place on the national stage. They are gone now. It would be worth our time to inquire why they disappeared, where they went, and whether—should such a thing be thought desirable—they might return.

Jacobs’s suggested answer is that Christian intellectuals “chose to disappear,” vanishing from public life either into a more privatized religious experience or, more significantly, into their own “subaltern counterpublics.” As they were less likely to be given space in the standard organs of public discourse—the magazines and newspapers, the talk shows and radio programs—they formed their own contexts and structures of discourse. As Jacobs observes, “Subaltern counterpublics are essential for those who have never had seats at the table of power, but they can also be immensely appealing to those who feel that their public presence and authority have waned.”

Where Did the Christian Intellectuals Go?

These subaltern counterpublics—Christian colleges, publishing houses, journals, and so on—proved successful and nurtured many brilliant minds. But there was a problem: they weren’t driving the public conversation. What’s more, many Christian intellectuals wondered if gaining a seat at the table would be a hard struggle with limited rewards. The price of admission was simply too high now that the clarity of a Christian voice would be stifled by the operating rules of liberalism. So remaining in segregated Christian institutions appeared to be a more prudent course of action.

Jacobs contends this “anti-intellectualism” in America ultimately lowered educational expectations for clergy. He also notes a corresponding distancing effect on the remnant of Christian intellectuals like Marilynne Robinson. Commenting on Robinson’s apparent distance from Christians who don’t share her more liberal political and social convictions, Jacobs writes:

When we read the great Christian intellectuals of even the recent past we notice how rarely they distance themselves from ordinary believers, even though they could not have helped knowing that many of those people were ignorant or ungenerous or both. They seem to have accepted affiliation with such unpleasant people as a price one had to pay for Christian belonging; Robinson, by contrast, seems to take pains to assure her liberal and secular readers that she is one of them. [From the same essay, quoting Robinson: “I have other loyalties that are important to me, to secularism, for example.”]

Reading Jacobs’s brilliant and frequently perceptive essay, I was struck by a curious absence at the heart of his analysis: the barely explored role of mainline churches in the developments he discusses.

Fading Backdrop of Mainline Denominations

This dimension of the story comes to the fore in an essay by Paul Gleason, in which he discusses the vaunted place of Robinson against the fading backdrop of American mainline denominations. Gleason describes the mainline as “a collection of Protestant denominations with deep roots in European history, reliably liberal politics and, if current demographic and attendance trends continue, just a few decades to live.” Yet until the middle of the last century—a key turning point in Jacobs’s narrative—these denominations had many millions of members and “included almost all of America’s political and cultural elites.”

Robinson herself is a Congregationalist, and one of the few remaining Christian public intellectuals within the mainline. She speaks with conviction for the liberal Christian tradition—and against the Scylla of a sectarian Religious Right and the Charybdis of a left-leaning secularism that is “contemptuous of religion.” She highlights the historical importance of the mainline tradition’s championing of reform movements: abolitionism, first-wave feminism, and civil rights. However, Robinson argues, the mainline churches have neglected to educate their own in the convictions that inspired these causes. So they’ve fallen into profound decline, with grave consequences for our nation’s public life.

Another Narrative for the Mainline’s Decline

Gleason advances a different narrative. By his estimation, the decline of the mainline occurred because the leaders of Robinson’s generation pursued their social missions “not by engaging more deeply with their history and doctrines, but by deliberately casting history and doctrine aside.”

Up through the 1960s, members and institutions of the Protestant mainline dominated American public life. To be sure, this dominance was not without serious issues—most notably, the exclusion of “Catholics, Jews, blacks, and atheists from nearly every position of influence in American life.” The significant demographic changes brought about by post-war immigration did nothing but exacerbate this problem.

Through these developments, influential mainline thinkers such as Harvey Cox and Paul Tillich responded by abandoning Christian particularism. Gleason writes:

They focused on the church’s social obligations, which they emphasized at the expense of the exclusivity and particularity of traditional doctrinal claims. In one famous formulation, Tillich argued that Christianity was just one of many ways to touch “the ground of being.” Symbols, religious and otherwise, all inadequately represented their ineffable subjects, but they also pointed beyond themselves to this ground of being, which Tillich called God. If Tillich was right, then mainline Protestants had no reason to distrust people of other faiths. Perhaps their beliefs were not so different after all.

This liberal thought was disseminated to millions of congregants by mainline Protestant clergy. They taught the values of “individualism, tolerance, pluralism, and emancipation from tradition”—and, in so doing, played a pivotal role in creating the culture in which we now live.

By virtue of their very “success,” however, mainline churches became a “vanishing mediator.” They made possible a passage whereby a new social order was founded from an old one. At the same time, these churches necessarily sank into invisibility as their movement was accomplished. Discussing Robinson’s treatment of the gay marriage debate, Gleason writes:

Why is this controversy, insofar as it is conducted in the language of religion, so one-sided? She never considers what, for her, would be a painful answer. Liberal Christians no longer need theology to make their case. They can couch their argument entirely in terms of secular political rights (as Robinson does here). In fact, arguments based on rights were probably more convincing than theological arguments even to them. The mainline remains as committed as ever to the social causes of our day—to gay rights, immigration reform, and a stronger social safety net. They still decry racism and economic exploitation, too. They’ve hardly remained silent, but there’s a reason you can’t hear them anymore. They sound just like everybody else.

In other words, the dinosaurs weren’t wiped out. They just evolved into birds.

When Did Intellectuals Vanish from the Public Eye?

Returning to Jacobs’s thesis, it’s clear that many dimensions of his picture make more sense when placed against the background of Gleason’s analysis. Put simply, the marginalization of Christian intellectuals must be interpreted in light of both the vast reconfiguration of the public square and also the transformation of the mainline.

It’s also noteworthy that almost all the Christian intellectuals Jacobs discusses, whether historic or contemporary, belonged to the Protestant mainline rather than evangelical denominations. Outside the context of the mainline, evangelicals never enjoyed the status of public intellectuals, even as they often functioned as important figures in populist and mass movements and accordingly enjoyed a measure of political influence (à la Billy Graham).

I suspect the twin movements of anti-intellectualism and anti-populism in the United States cannot adequately be told without reflecting on the split of mainline Protestantism into, on the one hand, de-institutionalized fundamentalist and evangelical movements and, on the other, a culturally elite yet increasingly faithless institutionalism.

Jake Meador has discussed this breach in American society in terms of culturally and institutionally sequestered intellectuals and a populism fuelled by mass media. Although a radically transformed media ecology has much to do with the American public’s realignments and reconfigurations, the fracturing of the Protestant mainline remains an essential part of the picture if we want to understand intellectuals’ separation from the public.

Why? Because mainline churches were the primary institutions that held these parties together. Yet as believing congregants abandoned mainline institutions for more populist movements, and as the mainline vanished into a post-Christian cultural elite, American society was riven apart—and a deepened antagonism between intellectuals and the public arose.

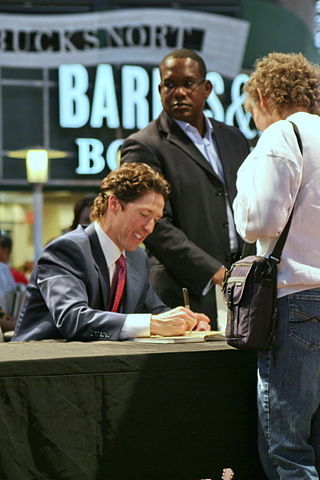

Why Joel Osteen Thrives and Books & Culture Dies

Living in the aftermath of this tectonic shift, today’s American Christian intellectuals are severely restricted in their cultural influence and potential. Those of us who operate within evangelicalism must negotiate a populist climate that’s poorly networked and thus ineffective at cultivating, establishing, and maintaining elites. Evangelicalism is a populist movement in that it was founded on patterns of mass consumption; it’s a movement within which a person like Joel Osteen thrives, yet a publication like Books & Culture perishes.

Great art, culture, and learning has generally depended on the support of elite patrons and institutions, not least the church and the state (perhaps especially monarchies). In mass, populist, or highly democratic movements, such excellence receives much less support. The existence of a thriving “high culture” or academic elite requires non-democratic structures that are harder to develop in a mass society. Where mass culture prevails, there’s often a pressure to cater to less cultivated tastes or, alternatively, to rebel against them in dysfunctional ways that signal an elite status.

In a former world, the power of the highly structured mainline churches and their wealthy and elite members enabled them to sustain a Christian high culture and a culture of academic excellence. Yet the most talented and least populist evangelicals today, because they’re cut off from previously powerful institutions, are likely to be poorly supported, underdeveloped, or marginalized.

Danger of Evangelical Fiefdoms

In evangelicalism’s “subaltern counterpublics,” intellectual discourse has struggled to attain the same height. Many of us have had to pursue our education in secular or Protestant mainline institutions, recognizing that evangelicalism hasn’t proved capable of sustaining the same culture of academic excellence.

In a populist movement, great talents can remain dangerously unchecked. On account of our institutional tendencies, evangelical ministries can easily become dominated by one or two brilliant minds or charismatic personalities. In fact, when these ministries don’t operate within larger institutions that sustain elite cultures of excellence—in institutions where great minds keep each other in check—gifted evangelical leaders can develop their own little fiefdoms, cut off from external challenge.

Such people don’t face enough pushback, friction, and criticism, and so their weaknesses and failings get writ as large upon their institutions, as do their strengths. Their thought is poorly honed and careless, where a robust culture of excellence would have forced them to be more rigorous. Although the leaders themselves may be blamed for this problem, I contend it is mainly an issue with the culture. Being big fish in evangelicalism’s small ponds, they often so dominate their context that they develop a cult-like following, whether they like it or not. Unfortunately, many do like it. After all, facing regular and robust challenge is not something we tend to appreciate.

Do These Roads Lead to Rome?

All this is one of the underlying reasons, seldom mentioned, why so many formerly conservative Protestant scholars and writers have gone in the direction of Rome. Conservative Protestantism has an impoverished elite, an unimpressive scholarly culture, and is poorly networked. With the rank apostasy of mainline Protestantism and the exodus of conservatives from such institutions, conservative Christian thinkers feel as though they have no intellectual home. What’s more, they operate in a culture that is more populist in orientation, which can stifle excellence rather than empower it.

Evangelicalism doesn’t produce intellectual and cultural elites like Rome and the mainline traditionally have. Nor do we have strong academic and higher cultural networks. Granting this, it’s no surprise Rome attracts some conservative scholars and writers who wish to make an difference.

Road Ahead

Currently we face another critical juncture in the development of the American public square and Christians’ place within it. An increasingly dominant secular liberalism antagonistic to orthodox Christian faith will only accelerate the process of squeezing evangelicals out of public life.

For evangelicals, this blow may be of truly catastrophic proportions, as it would devastate even the limited culture of excellence we currently preserve within our subaltern counterpublics. We depend in great measure on the government to sustain our academic institutions and would be unable to support many of them without this aid. Within the next decade or so, we should brace ourselves for the real possibility that many churches will lose tax-exempt status and many evangelical institutions will lose federal loan money. With such a loss, evangelicalism’s populist character would become even more stifling, and the evangelical mind may wither away at a terrifying speed. As a friend of mine recently remarked, the need to establish effective new institutions is now a matter of the greatest urgency. We’re entering a time in which we must accomplish immensely more with drastically diminished resources.

Free eBook by Tim Keller: ‘The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness’

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

Imagine a life where you don’t feel inadequate, easily offended, desperate to prove yourself, or endlessly preoccupied with how you look to others. Imagine relishing, not resenting, the success of others. Living this way isn’t far-fetched. It’s actually guaranteed to believers, as they learn to receive God’s approval, rather than striving to earn it.

In Tim Keller’s short ebook, The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness: The Path To True Christian Joy, he explains how to overcome the toxic tendencies of our age一not by diluting biblical truth or denying our differences一but by rooting our identity in Christ.

TGC is offering this Keller resource for free, so you can discover the “blessed rest” that only self-forgetfulness brings.