Some years ago, the late film critic Roger Ebert weighed in on the debate over whether video games could be art: “Let me just say that no video gamer now living will survive long enough to experience the medium as an art form.” Oh, Ebert. I love you, and I miss you, and how strongly—achingly, even—I wish you were right. For if what you said was true, then I wouldn’t have to wipe these tears from my eyes.

This weekend I played “That Dragon, Cancer,” an autobiographical video game that tells the story of the Green family and their son, Joel, who was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive cancer at the age of one. Joel battled his cancer for four years, overcoming repeated terminal diagnoses until dying at the age of five.

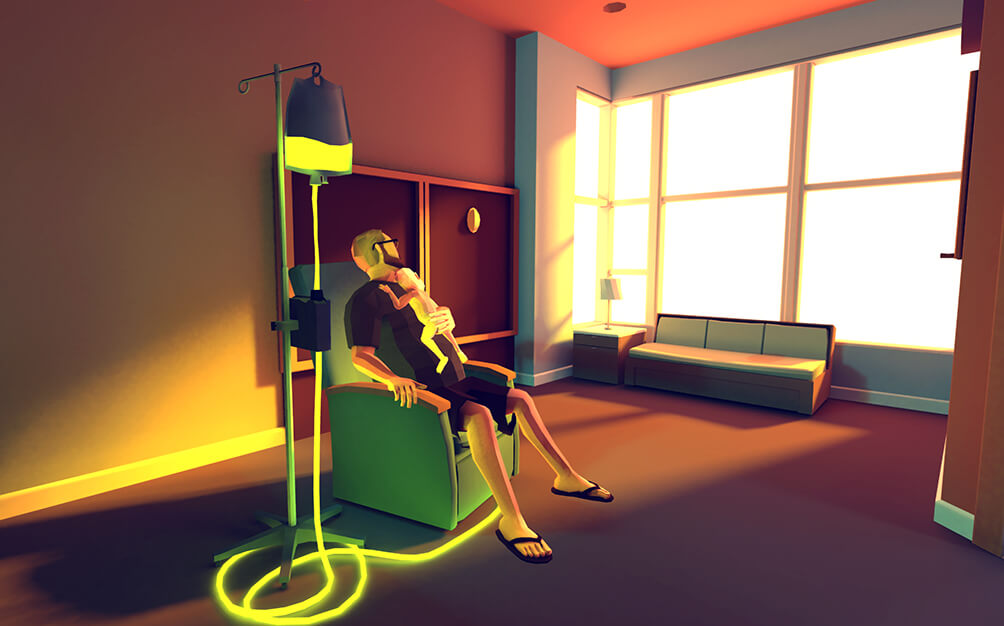

Over the course of about two hours, players accompany the Green family through Joel’s diagnosis, treatment, and death, alternating between hospital rooms and surreal, fantasy-like vistas that make up the landscape of unspeakable grief.

Along the way, players sit in on joyful picnics and frightening doctor visits, listen to frantic voicemails, and read letters of both mourning and encouragement. It is the anguishing record of a family’s journey through tragedy, and there is nothing quite like it.

Difficult Game

As you can imagine, “That Dragon, Cancer” is a difficult game. Not in the traditional sense of game difficulty, of course—it requires neither physical dexterity nor quick reflexes. You cannot fail the game. You will not run out of lives and find yourself at the start again. In fact, it rarely asks you to do more than move the mouse cursor and click on objects.

The game’s demands aren’t physical. Rather, they’re emotional and spiritual. “That Dragon, Cancer” requires the player to enter into the grief of the Green family and walk with them as they lose their son to a frightening and relentless illness. Courage is what’s needed.

“That Dragon, Cancer” is a hard experience to reduce to language, and perhaps this is part of why Ryan Green, Joel’s father, chose the medium of video games to tell the story. Things like sorrow, pain, fear, and doubt can be named and, to a certain extent, described; but as long as they are mere words and concepts their power is limited.

We can keep a clinical distance from the aesthetic experience of grief as long as we know grief only as an abstract idea on a page. In the game, though, we’re utterly submerged in the nightmare, and the parents’ helplessness and sadness is made our own.

Theological Heft

Often, the allure of video games is that the player is granted special power and agency. One becomes a soldier, business magnate, or superhero at the press of a button. “That Dragon, Cancer” frustrates and subverts the normal expectation of agency. Players are given game-like tasks, like navigating Joel through a field of cancer cells as he clings to a handful of balloons, or racing a wagon through the hospital.

Often, the allure of video games is that the player is granted special power and agency. One becomes a soldier, business magnate, or superhero at the press of a button. “That Dragon, Cancer” frustrates and subverts the normal expectation of agency. Players are given game-like tasks, like navigating Joel through a field of cancer cells as he clings to a handful of balloons, or racing a wagon through the hospital.

The facade of power and control crumbles away. It’s a brilliant piece of artistry in terms of video game design and theological heft; we players, accustomed to the power to trample our enemies, are shown our impotence in the face of a broken and fallen world. Our works cannot save Joel.

The overall effect is devastating. I cried multiple times, and I even had to stop the game to go hold my infant daughter. I’ve never had a game move me so much.

Hope

Yet for all the pervasiveness of fear and hopelessness, there’s another, greater theme: hope.

Ryan and Amy, Joel’s mother, are Christians, and they’re explicit about their faith. They pray often and sing worship songs, and they find encouragement in the small victories in Joel’s battle. In one scene, the parents explain Joel’s cancer to their other sons as a battle between Joel the Knight and a wicked dragon. Grace is Joel’s superpower, and it’s what helps him climb the mountain to face the dragon. In another scene, Ryan is overwhelmed by his inability to soothe a wailing Joel, who vomits any liquid he drinks. Ryan collapses into a chair and utters a desperate prayer, which is answered with Joel at last falling asleep. It’s a small miracle, but one met with gratitude.

This is a remarkable portrayal of faith. The game isn’t preachy, and there’s no prosperity gospel promise that faith results in material health and wealth. Joel’s parents genuinely struggle. Amy is desperate for a healing miracle that never comes; Ryan expresses doubts that God even cares.

The game didn’t have to be this honest, but it is, and this makes it a powerful witness. It shows the horrible condition of the world, and it offers hope for something better. In the end, through the heartache and loss, the Greens remain hopeful and true to their faith.

Game-Changing

“That Dragon, Cancer” is powerful. So powerful, in fact, that some gamers have vocally refused to play it, for fear of how it might affect them. The old narrative is turned upside down: We used to mock Christians because they were afraid of the effect video games might have on people. Now, gamers are the ones afraid of a game’s impact. It’s an incredible thing, and it shows how much the medium has matured.

In an era where so much Christian creative produce is either kitsch, Jesus-themed counterfeits or, at its worse, edutainment, “That Dragon, Cancer” stands out as authentic in both form and content. It is lamentation literature in digital form, A Grief Observed for the Nintendo generation. Like C. S. Lewis’s essays that recount the passing of his wife, this game is haunting and brutally personal. It plays by the conventions and trends of the video game medium and at the same time subverts them, exposing the illusion of total agency and control in our lives for the farce it is. It is a heartbreaking adventure that’s also an excellent work of artistry and a faithful witness to the hope of the gospel.

This one’s a game-changer.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.