Listen or read the following transcript as D. A. Carson speaks on the topic of Prayer from 1 Kings 18:1–46

The Bible speaks of God as the King. Sometimes, however, the notion of kingship is not transparent. This is not only because we sometimes mean something a little different by kingship today than what was understood in the first century or a thousand years before Christ, but also because the notion of kingship varies a bit from text to text within the Bible itself. I think we will better understand the passage before us, 1 Kings 18, if we pause for a moment to refresh our memories with three important distinctions.

1. God is not a constitutional monarch.

Since I’m a Canadian, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is my queen, my monarch, as much as yours. However, apart from her moral suasion, the advice that she gives, and her theoretical power not to sign into legal enactment something that Parliament passes (which right she would not exercise because there would be an immediate dissolution of Parliament, and she would be forced to sign it the next time around), she really has very little power.

The notion of a constitutional monarch is a modern one. If you want to think of an appropriate model for monarchy, you should think not House of Windsor but House of Saud in Saudi Arabia. It is an absolute monarchy. In fact, many occurrences of the word kingdom really mean something like king dominion or reign. The notion is not so much of a static kingdom with borders, such as the United Kingdom, and outside of those borders, there is something else. Rather, the kingdom of God speaks of the reign of God. God actively reigns. He is the King.

Nowhere is this made clearer than in some of the spectacular visions of the throne room of God, cast in colorful apocalyptic imagery, but most revealing. For example, the one in Revelation 4 pictures these elders, each with a crown on his head, casting his crown before the throne. It is a way of saying that all authority that we have is derived. All authority but God’s authority is derived and all kingly pretension is nothing more than the delegation of God’s authority. God alone is King. God reigns.

2. Although God is always sovereign, his reign is currently contested.

God’s reign is not pictured as the decree that enacts such judgments that we become mere machines. His reign is currently contested, but one day, his reign will no longer be contested. There will not be rebellion in the new heaven and the new earth. So we are taught to pray, “Your kingdom come, your will be done on earth as in heaven.”

3. The kingdom of God language in Scripture can sometimes be used of that subset of God’s total reign under which there is life.

Sometimes, the Bible sometimes speaks of God’s kingdom and his reign as his active sovereignty over all, but in many other passages, the Bible speaks of God’s kingdom and his reign as that subset of his total reign under which there is life, under which there is salvation, under which are found his covenant people.

So on the one hand, the big picture, the psalmist speaks of God’s kingdom ruling over all, including the armies of heaven and the hosts of human beings. According to Daniel, Nebuchadnezzar came to see that God’s kingdom is an eternal kingdom and that his dominion endures from generation to generation. The Most High is sovereign over the kingdoms of human beings, and he gives them to anyone he wishes.

As Paul puts it in his letter to the Ephesians, God works out everything in conformity to his own purpose and will. This may raise questions about the mystery of providence, but there is no legitimate question about the extent of God’s reign. There is a powerful sense in which God is sovereign over all.

Yet on the other hand, very often the locus of the kingdom is more limited. Thus, God is King over Israel. The King over Israel is, finally, God. He is not over the kingdom of Moab, not over the kingdom of the Hittites. There is a sense in which God has chosen Israel, because he has set his affection on her simply because he loved her, according to Deuteronomy 7 and 10.

Or in the New Testament, Jesus says unless you are born again, you cannot enter the kingdom of God. Well, in one sense, you’re in the kingdom, whether you like it or not. You only have to exist to be in the kingdom in the large sense, but in this redemptive sense, in this saving sense, one must be born again to be in the kingdom.

Or Paul, likewise, writing to the Corinthians, can say not everyone inherits the kingdom, and he describes the kind of conduct that is excluded from the kingdom. Then when Jesus talks of the kingdom in his wonderful parabolic stories, many of them describe the kingdom growing in some sense. Now the large kingdom doesn’t grow. It’s always there. God is sovereign all the time. His sovereignty is inescapable.

Yet he can speak of the kingdom growing the way yeast grows in bread, the way a little seed becomes a very large bush. He can speak of a seed falling into the ground and producing fruit with various yields. The kingdom, he says, is like that. In all such usages, then, the kingdom that is in view is that subset of God’s sovereignty under which there is a special covenant relationship with his people or under which there is life or the like.

Now this way of thinking about the kingdom inevitably produces a fundamental polarity in the Bible, a tension. It enables us to start speaking of the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of human beings, the kingdom of God versus the kingdom of the Devil. There is an absolute sense in which God remains sovereign over all, but in this smaller sense, there is this constant tension going on, a polarity that is found as early as the book of Genesis.

It’s found in individuals and it’s found in cities. It’s found in covenant communities. So there is an Abel, whose sacrifice pleases God, and there is a Cain, whose actions are such that his sacrifice does not please God. Or we come to the teaching of Jesus: The one vine has good branches, and it has bad branches. There are children of light and children of darkness.

The whole book of Revelation is sometimes summed up as a tale of two cities: Jerusalem and Babylon. Both are, of course, metaphorical ways of speaking of two whole domains. They are sometimes subtitled as “the bride” and “the whore,” precisely because, again, we have a polarity of entities: the woman riding on the Beast in chapter 17 and the New Jerusalem, seen as the bride of Christ in chapter 21. These are huge polarities. We live with those tensions.

Saint Augustine, in the fourth century, as the mighty Roman Empire was crumbling, the empire which for a century and a half had increasingly been identified with the Christian church (foolishly, no doubt, but that’s what had happened).… As the empire began to crumble, he wrote his famous book The City of God. He was trying to prepare Christians to make a distinction between what he called the “city of God” and the “city of man.”

All of our human cities, all of our human empires, bound up as they are with our loves, fears, lusts, failures, desires, and our desire for preeminence, all must one day crumble. One day, the kingdoms of this world became the kingdom of our God and of his Christ. He shall reign forever. So while Rome falls, the city of God does not fall. The New Jerusalem does not fall. There is a polarity between the reign of God, in this respect, and the reign of the Prince of the Darkness of the Air.

I hasten to add that this polarity does not mean that everyone under this saving kingdom of God is always pure and good. It does not mean that. Nor does it mean that everyone belonging to the kingdom of Satan is invariably devoid of all grace or insight. It does not mean that. Think of David, for example. He was part of the kingdom of Israel and a man after God’s own heart; nevertheless he fell into both adultery and murder.

Still, the fundamental point to be observed is an important one. The kingdom of God language in Scripture can sometimes be used of that subset of God’s total reign under which there is life. In other words, this way of talking about the kingdom of God forces us to think of kingdoms in conflict, and that is what is described in 1 Kings 18. It may help us to think through this narrative if we organize our reflections on it into four points:

1. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God may call forth hidden faithfulness.

First Kings 18:1–15. I’m going to take the time to read the first 15 verses to remind you of the account of Obadiah.

“After a long time …” That is, a long time of drought. “… in the third year, the word of the Lord came to Elijah: ‘Go and present yourself to Ahab, and I will send rain on the land.’ So Elijah went to present himself to Ahab. Now the famine was severe in Samaria, and Ahab had summoned Obadiah, who was in charge of his palace.

(Obadiah was a devout believer in the Lord. While Jezebel [the king’s consort] was killing off the Lord’s prophets, Obadiah had taken a hundred prophets and hidden them in two caves, fifty in each, and had supplied them with food and water.)

Ahab had said to Obadiah, ‘Go through the land to all the springs and valleys. Maybe we can find some grass to keep the horses and mules alive so we will not have to kill any of our animals.’ So they divided the land they were to cover, Ahab going in one direction, Obadiah in another. As Obadiah was walking along, Elijah met him. Obadiah recognized him, bowed down to the ground, and said, ‘Is it really you, my lord Elijah?’ ‘Yes,’ he replied. ‘Go tell your master, “Elijah is here.” ’

‘What have I done wrong,’ asked Obadiah, ‘that you are handing your servant over to Ahab to be put to death? As surely as the Lord your God lives, there is not a nation or kingdom where my master has not sent someone to look for you. And whenever a nation or kingdom claimed you were not there, he made them swear they could not find you.

But now you tell me to go to my master and say, “Elijah is here.” I don’t know where the Spirit of the Lord may carry you when I leave you. If I go and tell Ahab and he doesn’t find you, he will kill me. Yet I your servant have worshiped the Lord since my youth. Haven’t you heard, my lord, what I did while Jezebel was killing the prophets of the Lord?

I hid a hundred of the Lord’s prophets in two caves, fifty in each, and supplied them with food and water. And now you tell me to go to my master and say, “Elijah is here.” He will kill me!’ Elijah said, ‘As the Lord Almighty lives, whom I serve, I will surely present myself to Ahab today.’ ”

Elijah, apparently, has been living quietly in Zarephath, in a widow’s home, but now the time has come for God to restore the rain and to end the drought. To that end, Elijah is to present himself to King Ahab. After all, Ahab is not going to find him. He has been very vigorous in trying. In fact, Elijah himself has been living only a few miles away from the hometown of Queen Jezebel, in Jezreel, but still, he has been well hidden. Now God takes initiative to bring the two men together and to end the drought.

That’s how we are introduced to Obadiah. He is very interesting. On the one hand, he’s a devout believer in the Lord. His very name means servant of the Lord. Moreover, he treats Elijah with a kind of respect that shows he recognizes Elijah to be the true prophet of God. He himself has courageously hidden a hundred of the Lord’s prophets in caves and kept them alive using his power as the custodian of the palace, the one in charge.

At the same time, precisely because he is a high official in Ahab’s court and has peculiar responsibilities, he recognizes that his life is on the line. If Queen Jezebel finds out that he has hidden these hundred prophets, he’s toast. He wants to be sure that Elijah is not playing some wonderful religious trick on him. Elijah has been known to disappear rather spectacularly. He does not want to announce Elijah’s presence if the king is going to show up on the site and be unable to find him.

After all of these careful years of hidden faithfulness, is he now going to be slaughtered because of some stupid mistake from the prophet? The tensions in which Obadiah finds himself mean that he wants to be very clear that Elijah’s instructions will not compromise him. In due course, Obadiah complies, and the rendezvous between King Ahab and Elijah takes place.

It is at this juncture, then, that it is worth reflecting on the fact that in this man’s life, the absolute claims of the kingdom of God call forth hidden faithfulness. Obadiah’s ministry is not Elijah’s ministry. Elijah is going to move into massive confrontation. The mark of Obadiah’s faithfulness is quietness, even subterfuge, and a willingness to risk his life, but it is not exactly confrontation.

Compare, on another plane, the different roles in World War II, say, of the Dutch resisters who hid thousands and thousands and thousands of Jews, at the risk of their lives, and the role played by the soldiers who landed on the beaches of Normandy. They were quite different roles engaged in the same conflict.

We find something of this hiddenness in faithfulness in someone like Naaman. Do you recall the account in 2 Kings 5? After that spectacular healing, Naaman is convinced that the God of Israel is God, but he says to Elisha the prophet, “Only grant me this exception, this indulgence: Since I am, after all, the commander-in-chief of my pagan master’s forces and because he goes into the temple of his god leaning on my arm.… He’s an old man, and he takes my arm and leans on me. If I go in and make obeisance with him, grant me that indulgence.” Elisha says, “Go in peace.”

What must be clear is that for both Obadiah and Elijah, the absolute priority of God’s kingdom, of God’s rule, and of God’s right to rule, must hold sway, even if the ways in which faithful submission to the kingdom may issue in highly diverse functions and roles. What does faithfulness look like for Christians in the Southern Sudan, where two million have lost their lives in the last 30 years, and where they are now sending out missionaries into Muslim populations in the Cameroon? What does faithfulness look like there?

The absolute demands of the kingdom of God always call forth faithfulness amongst God’s people. How is faithfulness shaped there? How is it shaped on the streets of London? How is it shaped in a family where there is only one genuine, devout believer, and the rest are secularists and full of scorn for your foolish and immature right-wing beliefs? What does faithfulness look like there? When is it right, publically, to confront, as Elijah is about to do? When is it right to go underground, as Obadiah has done, to save a hundred of God’s prophets surreptitiously?

The first point, then, is really quite a simple one, but it is one that needs to be said because we so often think in stereotypical terms about Christian faithfulness. The point is this: the absolute claims of the kingdom of God may call forth hidden faithfulness.

2. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God may call forth dramatic confrontation.

First Kings 18:16–39. We now come to the passage that was read, beginning at verse 16 and running all the way down to 39. The critical meeting between Ahab and Elijah is not auspicious. When Elijah was confronted by Ahab, the king said to him, “Is that you, you troubler of Israel?” From Ahab’s point of view, the problem was Elijah.

In fact, the particular word that is used here, troubler, is rather a rare one. It first appears with respect to Achan. Do you remember the account of Achan in the book of Joshua? Because he compromised and stole some Babylonian garments and some silver when God had said not to, the whole army was under the ban and faced devastating defeat at the next town. Achan troubled Israel. He was a troubler of Israel. That’s the way Ahab views Elijah.

In that case, what would give Israel peace is to bump Elijah off, to get rid of him, as Achan himself was executed. Perhaps Ahab was tempted to a similar solution. Note, however, Elijah’s response in verse 18: “ ‘I have not made trouble for Israel,’ Elijah replied. ‘But you and your father’s family have. You have abandoned the Lord’s commands and have followed the Baals.’ ” In other words, the real trouble here is departure from the Word of God, departure from the command of God, multiplying idolatry.

In this country, if one seeks on occasion to correct the direction that some of our religious leaders are taking, almost certainly, even if we are basing ourselves powerfully on the Word of God, we will be called the troublers of the church, the divisive people, and the people who are upsetting the apple cart. Whereas, surely from God’s perspective, that which has been taught in departure from his Word is what is really troubling the church.

The fate of the troubler of Israel, Achan, had been settled before all of Israel, in Joshua 7. Elijah now wants a similar confrontation, hence verses 20–21. Ahab sends word throughout all Israel and assembles the prophets on Mount Carmel. Elijah then stands before the people and says, “How long will you waver between two opinions? If the Lord is God, follow him; if Baal is God, follow him.”

Now the expression in English, “How long will you waver between two opinions?” might conjure up people who are sharply divided or, perhaps, deeply uncertain. In fact, there are some cultures in the world (to some extent, ours) that like this sort of distance measuring of things: “Well, you know, they have something to be said for their perspective and yes, well, that god, too, has something to be said for his perspective. Yes, yes, I know we come from the religion of Yahweh, but there are a lot of people worshiping Baal these days.”

It might suggest that they are teetering, simply, between two opinions, but, in fact, it’s actually stronger language than that. It’s, “How long will you hobble?” Perhaps hobble at the crossroads, or even hobble on two crutches. You’re crippled and disadvantaged in the way you approach this entire thing.

Then a little farther on, in verses 26–27, the same language is used. It is, I’m afraid, gloriously mistranslated in the NIV. When the pagans are around the altar calling down fire from Baal, the NIV translation says they danced around the altar, but that’s not what the text says. It says they hobbled around the altar. It is as if, even by the narrative, the author is saying, “Don’t you see? The dance of faith is given away to the slow, crippled walk of sheer idolatry.”

More importantly yet, from God’s perspective, neutrality among his own covenant people is already betrayal. Supposing you take an oath to marry, for better or for worse, in sickness as in health, till death separates you. Then the years pass, you find someone else equally attractive, and you sleep with that person. Then you sleep with your spouse, and you waver between two opinions.

You’re crippled in your judgments. You’re distorted in the way you’re looking at all of reality. This is not neutrality. This is not some vantage point of superiority where you stand over the situation and make a careful, neutral, evenhanded assessment. This is betrayal. It is profoundly ugly betrayal.

So now the great God of the Bible calls forth Israel out of slavery, constitutes her a nation, gives her righteous government, raises up prophets, and institutes an entire sacrificial system by which the people are taught the principles of holiness and find a way by which their sins may be forgiven.

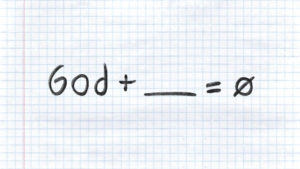

Now the people stand back and say, “Well, yes, he has done quite a lot for us, but then the Baals, too, they’re pretty hot stuff, religiously speaking.” It’s betrayal. It is idolatry. It is the de-Godding of God. What seems like a distanced neutrality by which we weigh all the options is already horrible idolatry.

So the stage, then, is set for the confrontation. Elijah says, “I only am left.” He doubtless means he only is left among the prophets free to move around the country and preach and so on, at this point. There are others, as we know, hidden in caves. Then the challenge is set forth: “The god who answers by fire, he is God.” Baal was supposed to be a fire god, so it seemed like a reasonable challenge.

The 450 prophets of Baal set out their sacrifice, and then they began to call on the name of their god. The mockery of Elijah is not gentle. He’s not trying to win an influence poll. He’s trying to show the starkness of the decision that must be made. “If this god is so powerful, well, call a little louder. He might be having a snooze. Perhaps he’s taking a walk. Keep at it. He’ll be home eventually. Wake him up!”

Now Elijah would not have had the confidence to do this had it not been for the simple fact that God had told him exactly what to do. Do you recall the prayer down in verse 36? “O Lord, God of Abraham, Isaac and Israel, let it be known today that you are God in Israel and that I am your servant and have done all these things at your command.” God was setting this up precisely so that there would be a very sharp confrontation for all the people to see.

Then when Elijah has his turn, he ups the ante by having a trench dug around the altar, pouring on gallons of water, and soaking the sacrifice and the wood. Then after a simple prayer to God, acknowledging that he is but God’s servant doing what God himself has commanded, God responds in fire and burns up not only the sacrifice but the very stones until there is nothing but scorched earth. The people cry out, “The Lord, he is God! The Lord, he is God!”

There have been a lot of other great confrontations in Scripture. Remember the confrontation between Moses, for example, and the magicians of Egypt? Or the confrontation between David and Goliath? There have been some pretty dramatic confrontations in the history of the church. Do you recall the account of Athanasius? In the fourth century, when almost all the bishops of the church were veering toward a denial of Jesus’ true deity, Athanasius stood up against them.

As he was preparing to go to a conference, a friend said to him, “Athanasius, do you not know that the whole world is against you?” Athanasius replied, “Then is Athanasius against the whole world.” That is either supremely arrogant or supremely humble. He was captured by what Scripture taught. He was prepared to argue the case in great detail, and he would not flinch. In God’s mercy, Athanasius won.

Or there is Luther, called before the Diet of Worms. He lays forth his understanding of justification by grace through faith, as taught in Paul’s letters, and he is told, “Do you not know that the whole church is against you? Will you recant?” What did he say? He said, “I need to think about it overnight.” That is what he said. As the story is told, we sometimes forget that bit. We come only to his heroic response the next morning, but he wanted to rethink again.

He went back to his room and thought, re-read Scripture, and prayed all night, because it struck him as astonishingly arrogant, even insolent, for one man to take on the doctors of the church. When he was brought back the next morning, he reiterated his understanding of Scripture, and then he said, “Here I stand. I can do no other. So help me God.”

Sometimes, the absolute priority of the kingdom of God calls for confrontation. Of course, the most amazing confrontation of all is one that took place on a little hill outside Jerusalem 2,000 years ago. It was the absolute demand of the kingdom of God that drove Jesus to such exquisite obedience. So we find him in the garden, “If it be possible, take this cup from me; nevertheless, not what I will, but what you will.”

At the very moment when all the hosts of darkness thought that by destroying the Son, they would bring destruction on all the saving plan of God, that very destruction guaranteed forgiveness for the people of God and was the step toward the resurrection where the power of God would raise the Son from the dead. All of gospel preaching, all of faithful witness, and all of Christian service, is the ongoing confrontation of the kingdom of this God, before the kingdoms of this world, in the name of this Christ.

In fact, we are told that this Christ is the mediator of God’s salvation. We are told all authority is given to him in heaven and on earth, and that all of God’s sovereignty is mediated through him. That is why some Christians speak of Christ as the mediatorial King. He must reign until he has put all of his enemies under his feet, and the last enemy will be death itself. For death is the last enemy. It does not have the last word. Jesus is the King. He is risen from the dead, and he will raise us from the dead too.

3. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God may call forth severe judgment and abundant blessing.

First Kings 18:40–46: “The people cried, ‘The Lord, he is God! The Lord, he is God!’ Then Elijah commanded them, ‘Seize the prophets of Baal. Don’t let anyone get away!’ They seized them, and Elijah had them brought down to the Kishon Valley and slaughtered there.

And Elijah said to Ahab, ‘Go, eat and drink, for there is the sound of a heavy rain.’ So Ahab went off to eat and drink, but Elijah climbed to the top of Carmel, bent down to the ground and put his face between his knees. ‘Go and look toward the sea,’ he told his servant. And he went up and looked. ‘There is nothing there,’ he said. Seven times Elijah said, ‘Go back.’

The seventh time the servant reported, ‘A cloud as small as a man’s hand is rising from the sea.’ So Elijah said, ‘Go and tell Ahab, “Hitch up your chariot and go down before the rain stops you.” ’ Meanwhile, the sky grew black with clouds, the wind rose, a heavy rain came on and Ahab rode off to Jezreel. The power of the Lord came upon Elijah and, tucking his cloak into his belt, he ran ahead of Ahab all the way to Jezreel.”

In other words, in the wake of this confrontation, there is, on the one hand, the most severe judgment for the prophets of Baal and the abundant blessing of rain. What are we to make of this? I suspect that it’s the first part that makes many of us nervous. It’s not very pluralistic, is it? It’s not very democratic. Leave them in peace.

Others will say, “Well, you understand that in the Old Testament, God is the God of judgment, but in the New Testament, God is the God of grace.” That won’t quite work. After all, the Old Testament pictures God as slow to anger and plenteous in mercy. He will not always chide. He remembers our frame; he knows that we are dust.

As a father pities his children, so the Lord pities those who fear him. The God of the Old Testament is often disclosed as a God of immense patience and forbearance. In the New Testament, judgment too is portrayed, is it not? Read the horrific scenes in Revelation 14 or Revelation 20. There is, finally, judgment to come.

I suspect the fact that we are more comfortable judgment with New Testament judgment than with Old Testament judgment is primarily because we are ourselves, today in our focus on the present and our current lives, more frightened of war, pestilence, and sword than we are of eternal judgment. That is a huge mistake. For just as God issues his temporal judgments on occasion and says, “Thus far shall you go and no farther,” so for all of history the time will come when he will say, “Thus far shall you go and no farther.”

I suspect some of us, today, are also a bit embarrassed by the blessings that come as well as by the judgment that comes. It just sounds a bit Pollyannaish. You have this big confrontation. Then God sends the rain, and everybody acknowledges that God is Lord. It’s sort of nice, isn’t it? A number of years ago, I was working on the book of Job, and I discovered that most modern commentators on the book of Job are deeply embarrassed by the last chapter.

Do you remember how the book of Job is put together? Job is made to suffer, under God’s sovereignty, because of the machinations of the Devil, on the one hand, and because God wants to show that he has a man, in fact, who will be faithful even under the most amazing sufferings. Job doesn’t know all of that. Job begins to suffer. He loses his wealth. He loses his family. He loses his health. He loses the support of his wife.

Then the miserable comforters come in and have all of this kind of tit-for-tat merit theology. “Oh Job, the real reason you’re suffering is because you’re so bad. If you would just admit that you’re bad, then God will take it all away.” Job says, “How can I admit that I’m bad when I haven’t done anything to deserve all of this?”

The argument goes on for chapter after chapter after chapter after chapter. The friends are disgusted with Job because he seems so self-righteous. He is disgusted with them because, from his point of view, they are trying to make him say something that he knows just jolly well isn’t true!

Then at the very end of the book, God speaks. “Job, have you made a snowflake recently? Did you cast Orion into the heavens? How about the hippopotamus, Job? Did you design that?” There are pages of rhetorical questions until Job begins to feel that maybe he isn’t big enough to understand it all, after all, and he says, “I’m sorry, Lord. I will shut my mouth.” Then God says, “Stand up like a man; I’m not finished yet!” and he asks him three more chapters of questions.

Now so far, the critics love the book: all this moral ambiguity, all of this uncertainty, and no real answer after all. It’s all bound up in mysteriousness. Then, in the last chapter, along comes God and gives him 10 more children (one wonders what his wife thought) and then doubles the herds of his flocks and animals and so forth.

The critics say, “Eh, eh, Pollyannaish.” It’s a bit like a 1950s Eisenhower-era cowboy film. You could tell who was the good guy and who was the bad guy by the color hat they wore. It destroys a good story: all this deep, deep moral mix-up and now a simplistic answer. The point that believers are to understand, however, is this: God wins.

God wins, and he vindicates his people, whether in this life or in the life to come. God is not anyone’s debtor. God is not the one who stands behind endless, bottomless moral ambiguity. God wins. Job 42 is an Old Testament promise of the New Testament promise that, in the end, God wins.

Here in this confrontation, again, God pours out his blessing. God wins. He does, in some sense, win the heart of the people. He pours out great blessing upon his people. He brings judgment to those who have defied the covenant, which was supposed to keep the teachers of the people of God pure. God wins. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God may call forth severe judgment and abundant blessing.

4. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God always call forth perseverance.

First Kings 19. Now Richard Bewes may have a word with me afterward because I am going to meddle a bit by saying something about the next chapter. I don’t know who is supposed to preach it next week, but it seems to me that the connection between the chapters has to be observed, and because they might not do it next week, I will do it this week!

For what happens next is that Elijah, now thinking that he has won a great triumph, thinking that the confrontation guarantees that Israel will be behind him, runs with Ahab to Jezreel, only to find that Queen Jezebel is going to kill him. The people do not stand up and revolt. The powers that be are still powerful. He runs into the desert and is in deep, deep, deep despair. He wonders if the whole thing has been worth it. “I, even I only, am left” becomes a cry of profound gloom.

Eventually, God confronts him, challenges him, and sends him to anoint a helper. The ministry of the Word of God goes on. It goes on in more prophets, in more ministry, challenging people with the Word of God. Do you see what it is a call for? Perseverance. Because, brothers and sisters in Christ, in this fallen, broken world, there is no utopia until the very end. It is desperately important that we realize that. There is no utopia until the end.

Almost every political party overpromises in order to get elected. The true believers in that party think that if only their platform can be put into place, maybe we can reintroduce utopia into this nation. Sometimes ministers of the gospel fall into the same pattern. “If we only adopt all of my theology or all of my methods, if we only do things exactly right, then there will be such great reformation and revival that the whole world will be evangelized and things will go swimmingly.”

What does Jesus say? “There will be wars and rumors of wars, but the end is not yet. In this world you will have tribulation. But be of good cheer! I have overcome the world.” It’s not as if God may not, in his mercy, bring about times of great reformation and revival. It’s not as if God does not sometimes bring down catastrophic and humbling judgment. Be certain of this, however: until the Lord comes, there is no utopia. Therefore, what is demanded of all of us, what is demanded by the absolute claims of the kingdom of God, is persevering faithfulness.

I happened to read something this week, written by John Stott, of whom you may have heard. “To perfectionists we say, ‘You are right to seek the purity of the church. The doctrinal and ethical purity of the church is a proper goal of Christian endeavor. But you are wrong to imagine that you will attain it. Not until Christ comes will he present his bride to himself as a “radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish, but holy and blameless.” ’

To defeatists we say, ‘You are right to acknowledge the reality of sin and error in the church, and not to close your eyes to it. But you are wrong to tolerate it. There is a place for discipline in the church, and even for excommunication. To deny the divine-human person of Christ is anti-Christ. To deny the gospel of grace is to deserve God’s anathema. We cannot condone these things.’ ”

Thus, the conflict of kingdoms goes on until Jesus himself comes back. By this very means, the gospel word goes forth, men and women are converted, and nations rise and fall. Churches experience reformation and revival, others abandon the truth and wither away until they are mere shadows of themselves, or, under the most violent persecution, may actually dissolve entirely (as in North Africa and in Albania under the communist regime).

Still, Christ Jesus says, “I will build my church.” He is the King. He reigns. The time is coming when the kingdoms of this world will become the kingdom of our God and of his Christ. The absolute claims of the kingdom of God demand, of all of us, perseverance, faithfulness, contrition, hope against hope, for the utopia that will be introduced when Jesus himself returns. Amen.