The Church: Universal and Local

Definition

The universal church is a heavenly and eschatological assembly of everyone—past, present, and future—who belongs to Christ’s new covenant and kingdom. A local church is a mutually-affirming group of new covenant members and kingdom citizens, identified by regularly gathering together in Jesus’ name through preaching the gospel and celebrating the ordinances.

Summary

The New Testament word translated into English as “church” (ekklesia) means assembly, and the New Testament envisions two kinds of assemblies: one in heaven and many on earth. These two kinds are the universal and local church, respectively. To become a Christian is to become a member of the universal church, whereby God raises us up with Christ and seats us in the heavenly place. Yet membership in the heavenly assembly must “show up” on earth, which Christians do by gathering together in the name of Christ through the preaching of the gospel and mutually affirming one another as belonging to him through the ordinances. The heavenly universal church, in other words, creates earthly local churches, which in turn display the universal church. Christians throughout history have sometimes emphasized the local or the universal church to the neglect of the other, but a biblical posture emphasizes both. Such a posture entails pursuing one’s individual discipleship in a local church, but a local church that partners with other churches.

Two Uses of the Word “Church”

What exactly is the church? A brand-new Christian who begins reading the Bible might find him or herself initially confused trying to answer that question. On one page, Jesus says that he will build his church, and that the gates of hell will not prevail against it (Matt. 16:18). The new Christian considers how Jesus uses the word “church” here and rightly conclude that he intends the church to be something broad, comprised of vast numbers of members from around the globe and over centuries of time. Then, a couple pages later, the young believer encounters Jesus telling the disciples they should address unresolved sin by telling it “to the church” (Matt. 18:17). Now he or she wonders if a church isn’t in fact a specific group of people located in one place.

Turning to Paul’s epistles similarly reveals two different uses of the word. In one moment, Paul talks about “coming together as a church,” like it’s an assembly (1Cor. 11:18). In the next he writes that “God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers,” like it is something much bigger (1Cor. 12:28).

What the young believer is discovering, of course, is how the Bible uses the word “church” in both a universal and a local sense.

At the most basic lexical level, the Greek word ekklesia, which English Bibles translate as “church,” means assembly. Yet Scripture employs the word to refer to two kinds of assembly: a heavenly one and an earthly one. Christians refer to these as the universal church and the local church, respectively.

Universal Church—A Heavenly Assembly

The universal church should come first in our thinking because people “join” the universal church or heavenly assembly by becoming Christians.

Salvation, after all, is covenantal. By the new covenant, Jesus Christ secured not just individuals but a people for himself, all of which he accomplished through his life, death, and resurrection. Yet by uniting a people to him, he also united them to one another. Listen to how the apostle Peter puts it:

“Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people;

once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy” (1Pet. 2:10; see also Eph. 2:1-21).

Peter places the second line about receiving God’s saving mercy in parallel with the first line about becoming God’s people. The two things happened together.

Fittingly, one crucial metaphor for our salvation is adoption (Rom. 8:15; Gal. 4:5; Eph. 1:5). To be adopted by a father and mother is to receive—derivatively but simultaneously—a new set of brothers and sisters. And this is the universal church—all the new brothers and sisters we have received from across time and around the world who belong to this new covenant people.

Why then say that the universal church is in heaven? Upon saving us by grace, Paul says, God “raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms in Christ Jesus” (Eph. 2:6; see also Col. 3:1, 3). By our union with Christ we are seated in the heavens, meaning, we possess standing and a place in God’s heavenly throne room. All the prerogatives and protections of that place belong to us because we are sons and daughters of the king. We are there. Yet Paul goes on: Not only have we been vertically reconciled, being raised up and seated in the heavenly realms. A horizontal reconciliation follows: “now in Christ Jesus you who once were far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ,” such that “he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one” (2:13, 14). Which means: if you are sitting with Christ in the heavenly realms, you are also seated with everyone else seated in those realms. This is the heavenly assembly, or the universal church, which Paul goes on to discuss in the following chapters (3:10, 21; 5:23–32).

The author of Hebrews highlights the heavenly location of this assembly even more explicitly for his Christian audience:

You have come to—the heavenly Jerusalem—to the assembly [ekklesia, or church] of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, and to Jesus, the mediator of a new covenant. (Heb. 12:22–24).

Again, how is it that the saints on earth could be assembled in heaven even now? Before the judgment seat of God, they have been declared perfect through Christ’s new covenant. There, in heaven, God counts all the saints, living and dead, as possessing standing.

Furthermore, this heavenly assembly anticipates the end-time assembly of all the saints who ever lived, gathered around the throne of God—what the apostle John calls “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb” (Rev. 7:9). For this reason, theologians refer to the universal church as not just a heavenly assembly, but an eschatological (end-time) one.

Definition 1: the universal church is a heavenly and eschatological assembly of everyone—past, present, and future—who belongs to Christ’s new covenant and kingdom.

This is the church that Jesus promised to build in Matthew 16. This is the entire body of Christ, the family of God, and temple of the Spirit. Membership comes with salvation.

Local Church—An Earthly Assembly

Yet a Christian’s heavenly membership in the universal church needs to show up on earth, just like a Christian’s imputed righteousness in Christ should show up in works of righteousness (Jas. 2:14-26). Membership in the universal church describes a “positional” reality. It’s a heavenly position or status in God’s courtroom. It is therefore as real as anything else in or beyond the universe. Yet Christians must then put on or enflesh or live out that universal membership concretely, just like Paul says we must “put on” our positional righteousness in existential acts of righteousness (Eph. 4:24; Col. 3:10,14).

In other words, our membership in Christ’s universal and heavenly body cannot remain an abstract idea. If it is real, it will show up on earth—in real time and space with real people, people with names like Betty and Saeed and Jamar, people we don’t get to choose but who step on our toes and disappoint us and encourage us and help us to follow Jesus. Membership in the universal church must become visible in a local gathering of Christians.

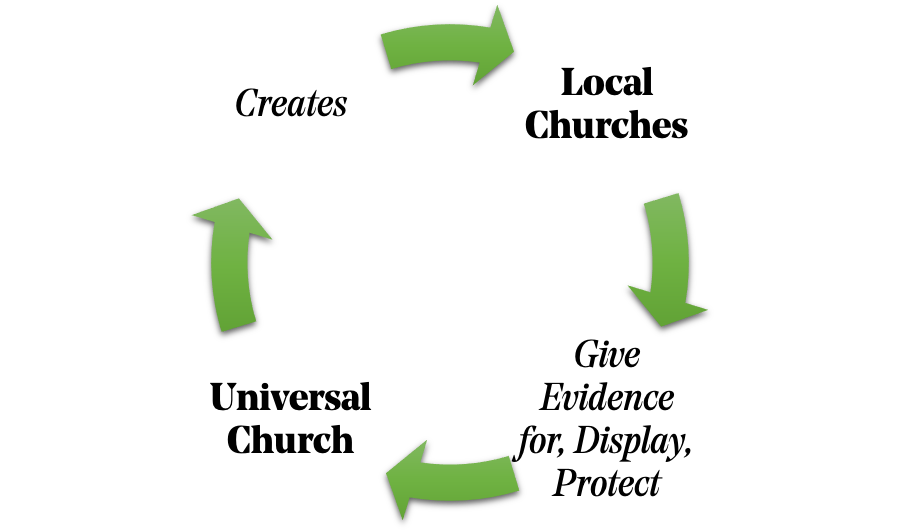

To summarize the relationship, the universal church creates local churches, while local churches prove, gives evidence for, display, even protect the universal church, like this:

Consider what this means: if a person says he belongs to the church but he has nothing to do with a church, one might rightly to wonder if he really does belong to the church, just as we wonder about a person who claims to have faith but has no deeds.

The local church is where we see, hear, and literally rub shoulders with the universal church—no, not all of it, but an expression of it.

It is a visible, earthly outpost of the heavenly assembly. It is a time machine which has come from the future, offering a preview of this end-time assembly.

Gathering, Mutual Affirmation, Preaching, Ordinances

More specifically the universal church becomes a local church—it becomes visible—through (i) a regular gathering or assembly of people (ii) who mutually affirm one another as Christians (iii) through preaching the gospel (iv) and participating in baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

Let’s back up and explain. Every nation and kingdom possess some way of saying who their citizens are. Today, countries use passports and borders. Ancient Israel used both circumcision and Sabbath-keeping, signs of the Abrahamic and Mosaic Covenant, respectively. The church is not presently a land-possessing earthly kingdom, yet this heavenly kingdom needs some way of affirming it citizens on earth, too. How does it do that? How can these heavenly citizens know who “they” are, both for their own sake and for the sake of the nations?

To answer that question, Jesus provided covenant signs for members of the new covenant: the entrance sign of baptism, whereby people are baptized into his name (Matt. 28:19); and the ongoing sign of the Lord’s Supper, whereby they affirm one another as members of his body (1Cor. 10:17).

Not only that, he gave local churches the authority to publicly affirm their members as citizens of his kingdom—to affix these covenantal signs on people, almost like a coach passing out team jerseys. To that end, he gave churches the keys of the kingdom to bind and loose on earth what’s bound and loosed in heaven (Matt. 16:19; 18:18). What does that mean? It means churches possess the authority to render judgment on the what and the who of the gospel—confessions and confessors. With the keys, he authorized churches to say, “Yes, this is the gospel confession we believe in and that you must believe in to be a member.” To say: “Yes, this is a true confessor. We will baptize her into membership” or “We will remove him from membership and the Lord’s Table for unrepentant sin.” In everyday terms, Jesus gave this gathered assembly the keys of the kingdom in order to write statements of faith and fill up membership directories.

So definition 2: a local church is a mutually-affirming group of new covenant members and kingdom citizens, identified by regularly gathering together in Jesus’ name through preaching the gospel and celebrating the ordinances.

Jesus describes this gathered local church in Matthew 18. It is an expression of the body of Christ, the family of God, and temple of the Spirit.

Early Church History: Leaning Toward the Universal Church

Through the history of the church, different individuals and traditions have emphasized either the universal or the local church.

In the first generations following the apostles, the emphasis rightly fell on both, at least as judged by early letters to churches and their leaders by pastors like Clement of Rome and Ignatius. The second-century document the Didache suggests likewise, with its dual emphasis on the practical workings of a local church and Christian faithfulness more broadly.

Yet just as people sometimes shift their weight off of both feet and onto one, so the writings of the church fathers moving into the third, fourth, and fifth centuries presents a growing emphasis on the universal church, albeit in an institutional guise. There were historical reasons for this. A number of theological heresies were cropping up. Also, churches divided over how to treat Christians (and bishops in particular) who denied Christ in the face of persecution but then asked for readmission. Such pastoral challenges prompted everyone from Cyprian to Augustine to emphasize the importance of being united to the one, holy, apostolic, and catholic—meaning universal—church. And unity with the one true universal church, they began to say, required unity with the right bishop; and unity with the right bishop, they eventually said, meant unity with the bishop of Rome, or the pope. In other words, catholicity or universality became an earthly reality as much as a heavenly one. It belonged to the institutional structures formally binding the global church together—an episcopacy supposedly tracing back to Peter and centering on the pope.

The Protestant Reformation would break this pattern by offering a more spiritual conception of catholicity. They, too, affirmed the necessity of external structures in the life of the church, but they also began to distinguish between the visible and invisible church. They argued that a person can belong to the visible church, but not the invisible church, or vice-a-versa, since salvation is not mechanistically gained through baptism or the Supper but only by regeneration and faith. This emphasis on the invisible church, then, effectively turned the catholicity or universality of the church back into a spiritual attribute, not an institutional one. The universal church, in other words, would prove on the Last Day to be the invisible church across space and time, not simply everyone who called themselves members of visible churches.

Later Church History: Leaning Toward the Local Church

That said, the earliest Reformers like Luther, Calvin, and Cranmer still maintained room in their thinking for an institutional form of unity and catholicity (universality). Their denominations were “connectional,” meaning, churches were formally and authoritatively connected to one another. By their lights, such formal connection was the requirement of unity and therefore catholicity. Hence, they treated the visible church as consisting of more than the local church—the assembly of people gathering in one locale. It also included larger church hierarchies, whether presbyteries or episcopacies. Hence, they would name their churches the “Church of England” or the “German Lutheran Church.” Not surprisingly, their theologies also emphasized the visible vs. invisible distinction as much if not more than the local vs. universal distinction. The practice of infant baptism, and the fact that unregenerate infants would be treated as members of churches, heightened the need for the invisible vs. visible distinction. After all, unregenerate infants belong to the visible but not the invisible church.

Within a couple decades of the Reformation, however, the Anabaptists and eventually the Baptists would more completely locate the unity of the catholic or universal church back into the heavens. They argued that every church should remain institutionally independent and consist only of believers. The visible church on earth, they argued, is only the local church and only the local church—the gathered, geographically-located congregation. The Church of England, they would say, is not a church. It’s a parachurch or administrative structure binding multiple churches together.

Yet among Baptist groups the risk now would be to shift the weight of the body entirely onto the other foot, where Christians would give all their attention to the local church and little to the universal. Certain strains of Baptist churches, such as the Landmarkists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, would in fact argue that only the local church exists. They would also refuse to share the Lord’s Supper with anyone who was not a member of their own church. Gratefully, such strains were rare.

Far more common has been the functional dismissal of the universal church among commercial- and marketing-minded church leaders in the late twentieth- and early twenty-first century churches. Such churches will verbally affirm the existence of the universal church. They will praise God for Christians around the world in their sermons. But their self-reliant church practices too often ignore the universal church. A marketplace mindset employs ministry language and methods that effectively promote a church’s own brand identity, like a fast-food restaurant promoting its own way of preparing hamburgers. This has the effect, presumably unintentionally, of pitting churches against one another. For instance, church mission statements, which have been popular in the last few decades, highlight a church’s unique mission emphases, as if Jesus did not give every single church precisely the same mission statement (Matt. 28:18-20). And this emphasis on what’s unique, instead of an emphasis on the shared partnership, corresponds to working separately from other churches, not together. So when a building is full, a church’s first instinct is not to plant another church. Instead it starts a second service or site. Churches might invite pastors from other countries to visit and share prayer requests on stage, but they won’t do this with a pastor from down the street.

Overall, the marketing and branding-heavy mindset does not entail opposing other churches, as it can among fast food restaurants. Yet it does mean nearby churches ignore one another. Worse, they have effectively placed themselves on a vast field of unacknowledged competition, where the most charismatic speakers with the best branding and programming draw numbers away from surrounding churches. Partnership among churches in the same neighborhood or city, then, is rare.

Emphasizing Both the Local and the Universal

Yet the biblical picture rests the body’s weight on both feet—the local and the universal.

The universal church “shows up” in local congregations, as I argued at the beginning. Yet it should also “show up” in every church’s disposition to partner with other churches, even as we see among churches in the New Testament. The New Testament churches shared love and greetings (Rom. 16:16; 1Cor. 16:19; 2Cor. 13:13; etc.). They shared preachers and missionaries (2Cor. 8:18; 3 John 5-6a). They supported one another financially with joy and thanksgiving (Rom. 15:25–26; 2 Cor. 8:1–2). They imitated one another in Christian living (1Thes. 1:7; 2:14; 2Thes. 1:4). They cared for one another financially (1Cor. 16:1–3; 2Cor. 8:24). They prayed for one another (Eph. 6:18). And more.

Christians today might disagree about whether the Bible means to establish institutional unity or connectivity between churches (I do not believe it does). But every local church should love the universal church by loving, partnering with, and supporting other local churches, including the ones nearest by. We should be willing to share the Lord’s Supper with baptized members of other churches when they visit with us.

Also, every denominational tradition should affirm that Christians must join themselves to local churches since theses local churches are expressions of the universal church. Our homeland in heaven has sent out ambassadors and built up embassies here and now. Those gathered churches are an outpost, a foretaste, a colony, a representation of the final gathering. If you belong to the church, you will want to join a church. It is where we put flesh upon our proclamation, our faith, our fellowship, and our membership in Christ’s body.

Further Reading

- Peter T. O’Brien, “The Church as a Heavenly and Eschatological Entity,” in The Church in the Bible and the World, ed. D. A. Carson (1987; repr. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2002).

- Mark Dever, “A Catholic Church,” in The Church: One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, by Richard D. Phillips, Philip G. Ryken, and Mark E. Dever (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2004).

- David Schrock, “An Ecclesiology of Churches: Why the Universal Church Is Best Regarded as a Myriad of Local Churches” (Nov 10, 2016).

- Stephen J. Wellum, “Beyond Mere Ecclesiology: The Church as God’s New Covenant Community,” in The Community of Jesus: A Theology of the Church, edited by Kendell H. Easley and Christopher W. Morgan (Nashville, TN: B&H, 2013).

- J. L. Dagg, “The Local Churches” and “The Church Universal” in Manual of Church Order (1858; repr. Harrisonburg, VA: Gano Books, 1990).

- Jonathan Leeman, “What Is a Local Church” (8/22/14).

- Jonathan Leeman, “A Church and Churches: Integration” (5/10/13).

- Jonathan Leeman, “A You a Universal Church-er or a Local Church-er?” (7/27/16).

This essay is part of the Concise Theology series. All views expressed in this essay are those of the author. This essay is freely available under Creative Commons License with Attribution-ShareAlike, allowing users to share it in other mediums/formats and adapt/translate the content as long as an attribution link, indication of changes, and the same Creative Commons License applies to that material. If you are interested in translating our content or are interested in joining our community of translators, please reach out to us.

This work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0