About 12 years ago, Time magazine ran a feature piece on the 25 most influential evangelicals in America. Included in the list were pastors such as Bill Hybels and Rick Warren, movement leaders such as Billy Graham and Charles Colson, and a few other public figures such as Senator Rick Santorum and then-White House adviser Michael Gerson. Around the time of publication, a reporter asked me who was missing from the list. I immediately replied, “Michael Cromartie.”

“Who’s that?” she asked.

“He’s the one who told Time who the 25 people should be,” I responded.

Michael the Networker

The Christian community lost a legendary leader on August 28 as Michael Cromartie, longtime vice president at the Ethics & Public Policy Center, passed away after a bravely waged battle with cancer. Cromartie was Christianity’s secret agent among the movers and shakers of American journalism, helping some of the nation’s top columnists and reporters better understand the faithful. Thanks to strategic funding once provided by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, Cromartie launched the Faith Angle Forum in 1999 with the goal of introducing a wide array of (mostly Christian) thinkers and leaders to top journalists.

Cromartie’s idea was simple: expose these smart reporters to thoughtful leaders from the world of faith and, in the process, news coverage touching on religion would become richer, more nuanced. Cromartie understood that educated readers would have to see Christianity as plausible in order to explore more fully the claims of the faith. So Cromartie, the best networked pre-evangelist working in Washington, helped journalists at major news outlets understand the plausibility of faith in modern society.

Cromartie was Christianity’s secret agent among the movers and shakers of American journalism.

Cromartie knew that the media often fell prey to two errors—taking American evangelicalism too seriously (being convinced it was behind every power structure in Washington), or not seriously enough (ignoring evangelicalism altogether). An energetic thinker himself, he fostered thoughtful dialogue among many different thinkers and, in so doing, elevated the public conversation about faith in American public life. Thanks to his efforts, the works of people such as John Stott were introduced to millions through a David Brooks column that came directly through the quiet influence of Michael Cromartie. In ways like this, Cromartie worked year in and year out; in the aggregate, Christianity became a more plausible, even attractive worldview to many once-skeptics.

Michael the Man

I first met Mike while I was a graduate student at Princeton. I went to see him as I embarked on a study of American evangelical leaders. I immediately liked him, for he seemed different from so many I’d met in the field. To have spent so much time in Washington, Cromartie had a remarkable ability to eschew the tendencies of well-connected Christians in the nation’s capital. He took a genuine interest in helping someone who had nothing to offer in return, and his generosity of spirit stood out as countercultural—at least to the extent anyone wearing a suit can be countercultural. So many journalists trusted him for a simple reason: he was a man of great integrity.

So many journalists trusted him for a simple reason: he was a man of great integrity.

In September 2004, Cromartie was appointed by President George W. Bush to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Twice he was elected chairman of this bipartisan group tasked with identifying areas in the world where people of faith need protection and greater freedom. His efforts helped countless persecuted groups receive the attention they needed from the U.S. government. When I last saw him earlier this year, we talked about troubling developments in places such as Malaysia.

As the president of a Christian college, I’m grateful for the legacy of Michael Cromartie. He embodies so much of what I prize about the evangelical tradition: passionate, Christ-centered, and outreach-oriented. And he avoided the pitfalls that entangle so many of us, reminding fellow evangelicals of the importance of justice and compassion while maintaining a posture of heartfelt humility. His was a public faith, one that drew even hardened skeptics to a deeper appreciation for the difference the gospel can make. We will miss him dearly.

Free Book by TGC: For Graduates Starting College or Career

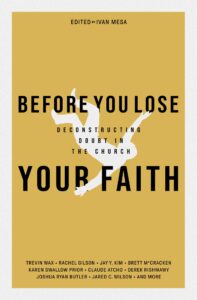

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!