Over the past year or so, the Washington Post has been running headlines like “The Boys Are Not All Right” and “Why Aren’t Men Going to College Anymore?” The New York Times called it a “Crisis of Men and Boys.” Most sources simply refer to it as “the boy crisis.”

The statistics are genuinely alarming: it sounds like boys are all going to drop out of school, quit going to work, and spend the rest of their lives watching porn, doing drugs, and playing video games in their basements while their moms do their laundry.

In 1982, men and women were attending colleges in equal numbers. Since then, women have outpaced men not only in college enrollment but in college completion and graduate school enrollment. For every four boys in college, there are six girls. In grad schools, women are outpacing men even in traditionally male-heavy programs like law school and medical school. Where are all the boys?

Here’s what I found out: Young men are actually going to college more than they used to. In 1970, about 20 percent of young men had a bachelor’s degree. By 2021, that was up to 36 percent.

It’s just hard to see the boys because there are so many more girls. In 1970, about 12 percent of young women had graduated from college. By 2021, that was close to 46 percent.

I know what you’re going to ask next: Why? Across the world, even across history, when girls gain access to the classroom, they tend to be more successful than their male peers. Girls do more homework and get higher grades than boys. They’re less likely to get into trouble, repeat grades, be diagnosed with learning disorders, or be expelled—even in preschool.

So that’s a problem, but not a new problem.

In the job market, fewer young men are working, even though there are now 5 million more job openings than unemployed people in our country. The percentage of men in the workforce dropped from 97 percent in 1967 to 88 percent today.

This trend has continued steadily for 50 years, regardless of changing market conditions or economic recessions or unemployment rates. The men who aren’t employed are more likely to have dropped out of high school and to have a criminal history, to be young, unmarried, and childless—or not living with their children.

So what do they do all day? National surveys show they’re spending most of their time—eight hours a day—on “socializing, relaxing, and leisure.”

That means lots of watching television. But it also means lots of video games. In 2017, the National Bureau of Economic Research released a working paper connecting the lower rates of working young men to the improvement in video game technology.

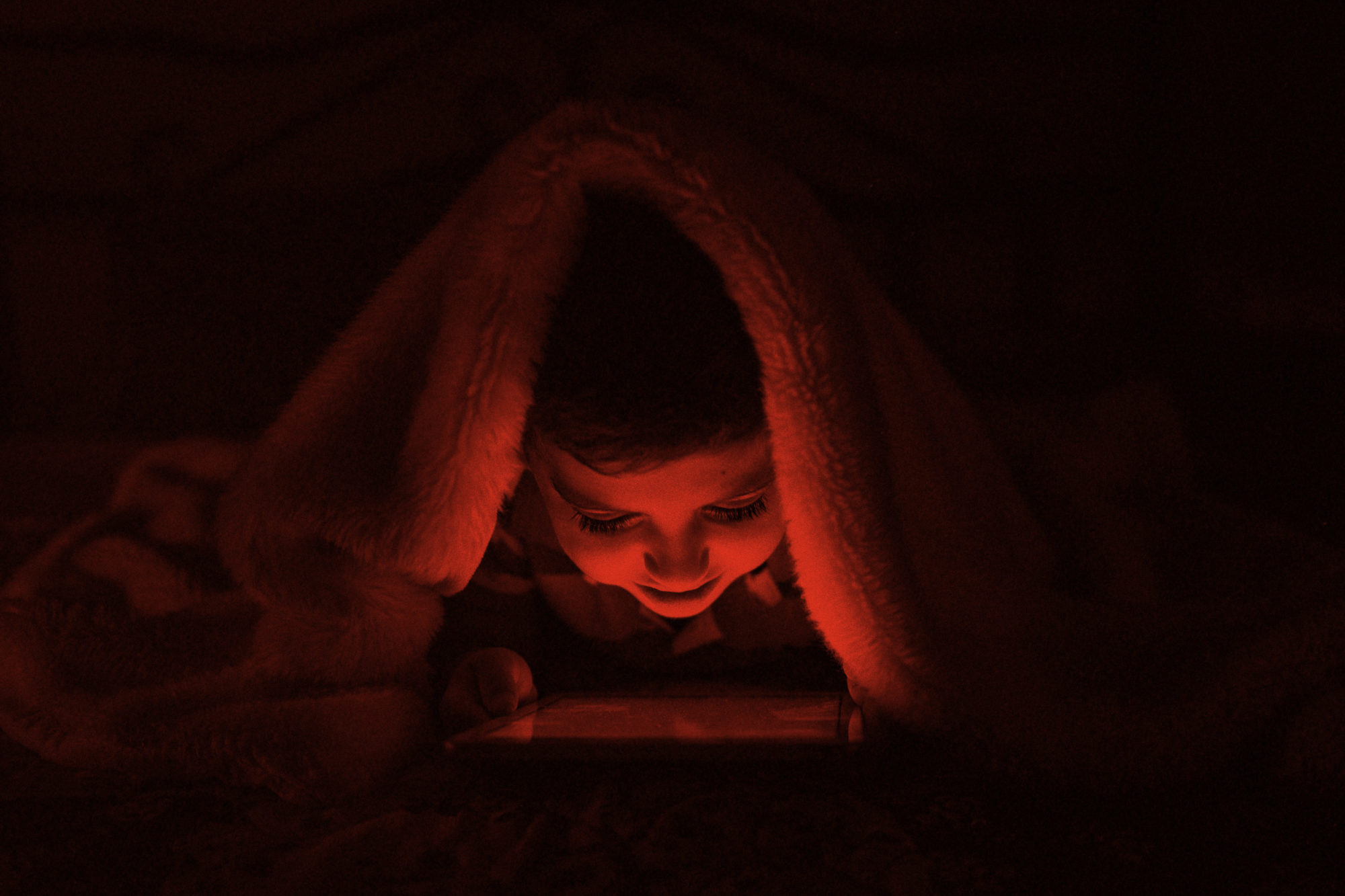

I’m not saying all male problems stem back to video games. But it is true that gaming has changed drastically over the past few decades. In 1999, about 50 percent of teen boys played video games for about 34 minutes a day. Today, 97 percent of boys play for an average of 2 hours and 20 minutes a day.

From Scrolling Alone to Gaming Alone

My first clue to what was going on with boys came from studying girls.

A few months ago, I did a podcast episode called “Scrolling Alone.” It was about how social media promises to be about connection and friendship but instead largely makes Gen Z women feel anxious and alone. Instagram and other platforms tangle young women in a cycle of digital comparison and competition, divorced from the in-person laughing and crying and hugging that enriches relationships. Social media isn’t wrong, exactly, but judging by the way it’s affecting young girls, we need to be a lot more careful with it than we have been.

Even before we published “Scrolling Alone,” I could see parallels with the world of video games. In both, you create and maintain an online identity in an online world. In both, you can meet and become friends with people across the world you haven’t met—and might never meet —in real life.

In both, you might aspire to be an influencer or a top gamer, which looks easy, like gaining fame and fortune by doing something super fun. But it’s actually a lot harder on you than it looks. In both, there are quantifiable markers—a score or a number of reshares or double taps—for how well you’re succeeding. In both, you can spend hours in front of a screen without much difficulty.

With the advance of technology, both forms of entertainment have grown really, really popular. Globally, social networking sites made $153 billion in 2021, more than twice as much as Hollywood, Starbucks, and the NFL combined.

The video game industry is bigger yet, raking in $180 billion last year. More than 40 percent of the 7.8 billion people on the planet play. In America, among teen boys, 97 percent play.

I’m not willing to write off either social media or video games completely. I’m a Reformed Christian, and I believe in God’s sovereignty over every square inch. So how can we think well—for ourselves and for our boys—about video games?

Meet the Players

“The first video game I ever played was Minecraft,” said Jacob Toole, a college junior. “I was 11 or 12 at the time. I remember very vividly getting my first laptop—buying it with my money that I’d saved up from working over the summer.”

Jacob is enrolled at Dordt University, where I got my undergraduate degree and where I now sit on the board. And yes, this is a school that’s so Reformed it’s named after the Synod of Dort, held by the Dutch Reformed Church in the 1600s.

To get there, I fly from Chicago to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and then drive about an hour southeast into the top corner of Iowa. The university sits in a little rural town surrounded by cornfields and big blue skies. It’s the kind of place where kids still walk to school by themselves, where grandpas gather in the mornings for coffee, and where 19 churches—12 of them with Reformed in the name—serve a population of about 8,000.

I’m here because while I was sitting in a board meeting last year, I heard about a gaming club that’s doing something no one else is—thinking with students about a Reformed theology of video games. More on that in a minute.

For now, I sit across the table from Jacob in a library conference room and ask what motivated him enough to work all summer mowing lawns to buy a laptop and Minecraft.

“Because I watched YouTube videos about it,” he told me. “Yeah, I knew that’s what I wanted from watching YouTube videos.”

Jacob loved Minecraft.

“[I] like the building, the exploring, the experience of having an entire world at your fingertips to do whatever you wanted with,” he said. “It was basically: get up, go to school, and then as soon as I got home, as soon as I got time—Minecraft.”

As he got older, Jacob built his own desktop PC. He got an account on Steam, which is a site where players can buy games, log their scores, or post reviews.

“I’ve put close to 500 hours on Age of Wonders III,” he said. “I’ve put many hours into Hearts of Iron IV, Stellaris—you know, all these different grand strategy type games. I put many, lot, hundreds of hours into these games.”

I asked what his mom thought about that.

“There were many times where she tried to institute something along the lines of, ‘You have X amount of hours per day,’” he told me. “That didn’t go too well.”

Addiction

Here we are, already at the heart of the problem. I can’t claim video games are the only thing that’s wrong with men in America—but I do know half of American gamers report missing sleep in order to play. A third have missed meals, and a quarter have skipped showers. More than 10 percent have missed work because of games.

The young men I talked to at Dordt looked clean to me. They played sports, sang in the choir, and had girlfriends. They went to class, got good grades, and were leaders on campus. But they could all get lost in digital worlds, and it could be hard to make their way back.

Johnny Sullivan is a senior engineering major. He attended a private Christian high school that wasn’t close to his house. I asked how much time he spent he playing when he was younger.

“If I’m honest, sometimes too much,” he said. “It definitely got to a point—like, it started out with the whole thing of my mom didn’t restrict too much of my time, because that was how I hung out with my friends, because I lived away from my friends. Then, that lack of restriction on the time, it wasn’t the greatest thing. Because I had trouble, and I still sometimes have trouble, budgeting my time. So yeah, that’s one thing me and my mom both wish that had been done differently.”

And here’s Ethan Haeder, who grew up connecting with his dad over video games. It was a great way for them to bond. But it was also hard to turn off, especially when he got to college.

“Second semester, freshman year, you could definitely make an argument that it was it was becoming an addictive problem for me,” he said. “I didn’t adjust to college life super well. So my first two semesters were tough because of video games. There was one Saturday when I realized that I had been at the computer playing for 15 hours straight—not straight, I got up to eat meals and to go the bathroom. But otherwise, I’d been playing for 15 hours. They were an enjoyable 15 hours—[but] probably not healthy. Definitely not healthy. . . . That’s too much of anything.”

He’s right, of course. Fifteen hours of anything is too much. But it’s rare that you can physically do much else for that long. If you tried to play sports for 15 hours straight, you’d collapse. If you tried to work for that long, you’d give out. If you ate for that long, you’d explode your stomach.

The unique thing about video games is that you can play them for a long time. They require very little physical energy, and the blue light from the screen keeps your mind from recognizing your body is growing tired.

This works for video game companies, who make money not just on the sales of their games but also by what’s called “in-app purchases” or “microtransactions.” That’s when you can buy something small—say, Fortnite skins or a specific weapon or extra lives—to make the game more enjoyable or to help you progress. I cannot emphasize enough how important this is. The average League of Legends player spent $92 on these game upgrades in 2019; the average Fortnite player spent $82. In 2020, players spent a combined $93 billion on microtransactions—that’s eight times more money than they spent on the games themselves. For comparison, that was more revenue just in microtransactions than Target made that year.

This is a massive economic incentive to keep players online. Over the years, through trial and error, video game companies have spent a lot of time and money figuring out ways to engage the human brain. One is to present someone with an achievable task and a clear path to success. Our brains release dopamine when that happens—we feel competent and happy. When it fades, we want to feel competent and happy again.

Another strategy is to offer someone an uncertain reward. In social media, that’s the question of how many likes or reshares a post will get. In video games, that’s a loot box you buy though you’re not sure what’s in it. Or it’s earning an arbitrary reward for completing a test—say, a random number between 1 and 10 coins instead of a stable, consistent 5 coins.

There are a bunch of other strategies as well, such as leveling up or tracking streaks, like playing every day for eight days. Or getting daily rewards. Or being penalized for taking a break—for example, your supplies might go bad or you don’t get any upgrades.

No wonder boys are having a hard time logging off.

Why Are Boys More Addicted than Girls?

“I’ve rationalized it as that’s what guys love to do,” junior Kayla Vande Zande said. “Where girls love to go shopping or we love to go on social media, guys love to video game.”

For a while, Kayla dated a boy who couldn’t put down the controller.

“He was putting off schoolwork to play video games,” she said. “And anytime I would go in [his dorm room] or any time I would talk to him, he was playing video games. Or that’s what I felt like, at least. I rarely saw him doing schoolwork.”

This is important. Because while about an even number of boys and girls play video games, those who are addicted are overwhelmingly male.

It seems like video games tap into something about the way God made men. When males conquer territory in a video game, a Stanford study showed the parts of their brain associated with reward and pleasure light up with dopamine. The female brain lights up too, but not nearly as much. Another study showed that males feel better about gaming wins, and not as badly about losses, as females. Their incentive is to keep reaching for those wins.

No surprise, then, that a sizable minority (some say up to 20 percent) of males really struggle to put the games down, especially in younger years while their brains are developing. The executive control center, which weighs risks and rewards, isn’t fully matured until around age 25, meaning kids and teens are more likely to favor the immediate gratification of a game than the delayed gratification of going for a run or finishing a paper. Studies bear this out.

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified “gaming disorder” in part as the escalation of gaming over negative consequences—in other words, even though you’re failing the class or losing the job or alienating the friends, you still keep playing. If this continues for at least a year, the WHO said, then you’ve got a gaming disorder.

“What makes anything addictive?” Jacob said. “It’s a stimulus that triggers a dopamine response. And then because of how our bodies are made, we want more of the stimulus. And especially with video games, that’s a pretty easy dopamine hit to get. So then you can just press the button over and over again, and you get there and all of a sudden, you’re trapped, and you’ve wired your brain in such a way so that is one of the few ways you can actually get the dopamine hit. You can’t like, get it normally anymore. And then you end up with problems.”

Jacob’s right. And when boys choose games over and over, they’re reinforcing neural pathways in their brains. They learn how to respond rapidly to large amounts of incoming information, which is good training for anyone who wants to be an air traffic controller. But it’s not great training for boys who need to practice focusing their attention on a single purpose, like reading a textbook, focusing on a task, or listening to a teacher.

And it’s not great for learning offscreen skills like navigating face-to-face conversations, finishing a boring job, or shooting a ball into a basketball hoop. While video games do hone digital hand-eye coordination, that doesn’t translate offscreen—in other words, playing video games doesn’t help you catch a ball or spot a moving target in real life.

Unfortunately, when those neural pathways become too entrenched, they’re almost impossible to resist.

None of these things is a secret. While not everyone has studied the research, anyone who has experience with a boy and a video game knows there’s potential for trouble. I’ve yet to meet a mother who is really happy with the way her son interacts with video games. My husband and I were so unimpressed with the effect video games were having on our 12-year-old we banned them altogether.

Robert Taylor, the vice president for student success at Dordt, felt the same way.

“We were starting to hear from students that they had interest in esports,” he said. “And I thought to myself, ‘That is the last thing that I even want to explore.’ Because I couldn’t see the value in it. And I had watched so many of our students struggle because of addictions to gaming.”

Confession: I talked to students and faculty at Dordt for three days before figuring out that esports has nothing to do with actual sports. It doesn’t mean playing Madden or NBA 2K against someone else. It means playing any video game—Street Fighter or Super Smash Bros. or League of Legends—in an organized competition.

Over the last four years, more than 200 esports programs have popped up at colleges all over the country. The main selling point for colleges is that they draw male students, which is important since nearly 60 percent of college students are now female. The selling point for students is you can earn scholarships for being particularly good. Plus, you get to play video games in school.

Robert wasn’t interested in esports at all; really, no one in Dordt’s administration was. But Robert’s boss had met a guy named Brad Hickey, who was at Fuller Seminary working on the world’s only PhD on video games and Reformed theology.

“Call this guy,” Robert’s boss said.

“This is a giant waste of time,” Robert thought. But he did it.

That phone call changed everything.

Redeeming Video Games

“I came from an extremely difficult background,” Brad Hickey told me. “Honestly, I went to a school for kids who are [troubled]. It’s the last stop before you’re out of the system.”

Brad’s first experiences with transcendence, with otherworldly beauty, with longing for something better, came through video games.

“God uses so many of the different spheres to reach people,” he said. “We think typically that it’s the church, this Augustine moment. That wasn’t the way it was with me. . . . I remember the first time I saw Super Mario Brothers or other games down the line, it did something inside me—wow, this music! This art!”

Back then, Brad had a massive stutter. “I couldn’t even order at a restaurant,” he said. “I had never really [found a place in] traditional places like church and family. I found a group online and we did all these amazing things together. They were people from around the world who had known each other for a while. It was an embodied friendship. I felt family and solidarity. They cared about me. If people got sick, they would go fly and visit them. They would go to each other’s weddings.”

It’s not an exaggeration to say God used video games to reach Brad, even to heal him a little, and to connect him to healthier human relationships. He’d grown up in an Assemblies of God church, but when he got to Fuller Seminary and Richard Mouw he started reading theologians like Abraham Kuyper, Herman Bavinck, and Josef Pieper.

“Then I started to push the church a little bit,” he said. “We say that every square inch [is under God’s sovereignty]. But we break off this one piece of culture as if it’s somehow inherently just evil—when in reality, God is active in those spaces, and God is calling us to redeem those spaces.”

That’s what he told Robert on the phone.

“It really hit me in that phone call that I had not been thinking about it in a very Reformed way,” Robert said. “And I pride myself in seeing all of creation has been God’s, and that we’re to be stewards of it, and that through the work of his Holy Spirit, we can be vessels of redemption. And so I felt pretty convicted about that.”

I felt convicted too, especially after reading these sentences from Brad’s dissertation: “Our role as God’s stewards requires us to make a genuine effort to understand what video games are and to speak authoritatively about them. To do otherwise would be to miss out on an opportunity to influence and enjoy a significant cultural space as well as to ignore new ways in which God is working in the world.”

OK, Brad, you got me. So tell me—how can we understand video games in a Christian way?

Theology of Play

Hang with me here. We’re going to get theological. Here’s what I learned from Brad’s dissertation.

First off, it seems clear we’re meant to play. In creation, God appears to play with color and light and sound. He plays through the creation of planets—from the expansion of the universe, we understand he’s playing still. Through the Old Testament, we see him playing in serious ways, offering tests to Job and Abraham and Jacob. And he plays in lighter ways—through the stories and parables Jesus tells his disciples, even in the hard questions that to them seem like riddles.

It’s almost impossible to define play. But we know it when we see it. We know it brings joy. We know it connects people. And we know it takes us out of ourselves—a girl with a dollhouse or a boy in the woods is in another world. A family around a board game, friends on a basketball court, or a teen with a book are all transported away. C. S. Lewis calls play “a pointer to something other and outer.”

Play can point us to eternity, to heaven. But it also teaches us how to live here and now. Play is one of the first things we look for in human development. Children play to practice adult roles; to develop physical, emotional, and social abilities; to discover their own talents and interests. Adults play to connect with family and friends or to relax their brains from the stress of labor. In a testament to how fun and generous God is, those breaks sometimes spark ideas or connections that help us in our work.

Without question, play is woven into the fabric of God’s good creation.

Playing to Connect with Others

“If you think about a good game of chess, what it’s really doing is teaching us how to have character, to have virtue, how to think about the person across from me,” Brad said. “If you think about the Scottish games, as they were originally, it was a way of diffusing anger between tribes through the use of play.”

Like the Scottish competitions, and like modern sports, video games can give players a safe way to be aggressive. They can bring delight. And they can connect people. I heard that over and over. Here’s Zach Brenner, a junior history major:

Every weekend in middle school in high school, or every day, really, we’d sit and we’d play. We’d get done with football practice, and then we’d go home and play video games. So that was always a lot of fun. Eventually, going into my junior year of high school, I moved to North Carolina, where I met a friend who he played a lot of Destiny 2. And so I played that with him. Through that I have made friends all across the country. It’s a lot of fun.

And Johnny:

I didn’t live near any of my friends from school, so I couldn’t really, like, easily go hang out with them. So video games was one of the ways that I would hang out with my friends, playing Minecraft with them online. That was the way that I would get to connect with them and get to hang out with them and keep those friendships.

And Jacob:

It’s a good avenue for shared interest in community and building relationships. And it’s, you know . . . a very good thing because it’s a lot easier to make friends with someone if you have some kind of shared interest.

So that sounds great to me, because I love friendships. And because I know friendships in America are fewer and thinner than they used to be, especially for men. In 1990, just 3 percent of men reported they had no close friends. Last year, that jumped to 15 percent.

For men under 30, it was 28 percent.

At first I blamed this on transience, because a lot of my friends don’t live anywhere near where they grew up. But the numbers don’t bear that out. Before the pandemic, Americans were an at all-time high of staying put. Back in the 50s and 60s, about 20 percent of the population moved each year. In 2019, that was down to less than 10 percent. Even young people—those from 20 to 30—aren’t moving as much as they used to.

So we’ve got a population that’s fairly geographically stable. And we’ve got huge social platforms on which guys can connect and play games together. Why aren’t men overloaded with friends? Why are they, instead, losing friends?

Gaming Alone

“We invited Brad to campus, and I just threw out to our men’s underclassmen buildings—about 400 men—if any of you have any interest in esports, we have someone working on a PhD who’s here, we’d like to do a little presentation and also a little Q&A and hear from you,” Robert said. “I sent it out the night before. And we had about 40 to 50 students come. And what shocked me was that I didn’t know those students—and I work pretty hard at knowing students on our campus. It’s getting to be bigger, so it’s harder. But still, in a group of 40, I felt like I didn’t know very many of them at all.”

That was concerning. But there was an even bigger problem.

“As we engaged with them, we began to understand that they didn’t know each other either,” Robert said. “This was truly a group of students that was highly engaged in their activity of gaming, with people all over the world, but they didn’t know the people that were living next to them or in their building. And that’s when I had a deep pit in my heart. I was grieving it, realizing we’re not impacting these students in the way that we strive to as a university.”

Oh. That’s not good.

It reminds me of social media, which promises to connect you with your friends and family but leaves young women feeling more isolated and lonely than they’ve ever been before.

Maybe video games promise adventures with friends but, in reality, isolate you in your room. But aren’t you literally playing with people? Aren’t they your friends?

Sometimes they are—guys you know from school or church or baseball. And sometimes they’re online-only friends. More than half of boys play video games with people they’ve never met—and probably never will meet—in real life.

I got more insight into this from Ethan.

“Probably the [person] that I’ve played with the most that I’ve never met is a guy—I have no idea what his real name is,” he said. “We all we call him Dirty Dan, because his username is Dirty Dan. And the most I know about him is he’s 16 and lives in Arizona. That is the extent of the information I have about him. Because all the rest I need to know is that he plays Destiny with us. And he’s funny, he’s nice. He’s really, really, really good at the game.”

OK, part of this I’m going to chalk up to differences between males and females. When my husband hangs out with his friends, he’s not asking nearly as many personal questions as I would. And when my sons were younger, they could play all day with a friend at the park or preschool and come home not knowing that child’s name.

But another part of me knows this can be a problem. If I hadn’t seen Ethan say hi to lots of other people on campus, if I hadn’t heard lots of other students tell me they know him, if I hadn’t met his wife, I would be really concerned. Because if you don’t know someone’s name, are they really your friend?

And if most of your social interaction is anonymous or online, is it really social interaction? Or are you really just gaming alone, next to other boys who are gaming alone?

I honestly do think video games can be a way for boys to enjoy friendships together. But if it’s all you do together, that’s a pretty shallow friendship. If most of your friends live in other cities, they can’t help you when your car breaks down, or come over for pizza on a Friday night, or join your church small group. In 1990, 45 percent of young men said they’d turn to friends first when wrestling through a personal problem. Today, that’s down to 22 percent.

Studies on video games and loneliness show that the motive for playing matters. If you play to be with friends, video games don’t make you feel lonely. But if you’re playing to escape from hard real-life circumstances, you feel more isolated. You’re also more likely to become addicted.

So it makes sense that boys who are fine in high school can struggle with gaming when they get out on their own or go to college, which are hard and scary things to do. Social anxiety can push a gamer to spend more time online, which in turn heightens his real-life social anxiety.

That’s what Robert was worrying about with his 40 students in that meeting.

“We probably had about 15 stay after,” he said. “There were tears as they shared their stories and feeling like they hadn’t been seen ever in their life. And there was this hope that seemed to generate from this idea that Dordt would even bring this guy here for that evening.”

Robert and Brad started talking about what it would look like for Brad to come and work at Dordt. At first, they were thinking he’d run something like an esports program. But the main point of esports is to be really good at gaming. The way you do that is by gaming all the time. Neither Robert nor Brad was up for that.

Instead, they wanted a program that would be Christian, that would be Reformed. They wanted something that looked different from the way the world did video gaming.

It was hard to find a pattern for that. Other Christian colleges have student-led gaming clubs or esports, and a few Christian professors have taught and written on video games. But Robert and Brad wanted to implement a program that would intentionally connect students to each other and to God, that would consider video gaming through a Kuyperian worldview. Nobody had done that before.

Turns out, they didn’t need to look to other colleges. They just had to walk across campus, where they found a model for what they wanted in the gym.

Video Games and Athletics

“In 2018, there were a number of us in the athletic department, along with campus leaders, who believed that there was a different and better way to do athletics than what society was telling us was appropriate,” said Ross Douma, the athletic director at Dordt.

Like Robert and Brad, he was in a field where it could be hard to identify the Christians.

“Even amongst Christian colleges and universities, athletics has sometimes been a bit of a one-off in that, yes, they’re connected to a Christian institution, but what’s transpired in athletics doesn’t always mimic what’s going on with the rest of the campus,” he said. “We wanted to have an athletic program that internally was really mentoring and witnessing and challenging our student athletes. And then externally, we wanted to be a department that was stepping into a space that was very polluted, very tainted. . . . We wanted to try to redeem and reclaim that as best we could.”

The sin Ross could see in athletics was a cousin to the sin in video games—basically, idol worship. Pursuit of your own glory. Winning at any cost. Chasing accomplishments. An unspoken rule that, really, this part of your life doesn’t have to come under the headship of Christ, because what would that even look like?

“The NFL plays on Sunday for a reason,” Ross told me. “And Saturdays is college football. So for four months, just using that sport alone, our entire week as a society is pretty much centered around—if college football is your idol, Saturday, and if the NFL is your idol, Sunday. And both of those sports creep into the worship of God, creep into family time.”

Like video games, sports appeal more to boys, and weirdly, for some of the same reasons. Athletics also offers a chance to compete, to conquer, to accomplish. It also offers instant validation. And if you didn’t win this time, sports also offers another chance to try again. That’s probably why, across cultures, males are more likely to play sports as kids, more likely to play as adults, and more likely to coach kids’ teams, college teams, and professional teams. (As a side note, they’re also more likely to skip church to watch sports.)

Like video games, youth sports were made possible by the incredible rise of technology, affluence, and leisure time in American society over the past 50 years. Like video games, organized sports seem safe to modern American parents. Tom Sawyer, Timmy and Lassie, or even Kevin from Home Alone were rough and tumble and free to roam, but their adventures seem downright dangerous to parents today, who’d prefer to have their boys where they can see them.

Like video games, sports seasons can become all-consuming. There’s a reason we call some wives “football widows” or “golf widows.” There’s a reason universities make allowances for the coursework of students who have heavy practice and performance schedules. And there’s a reason pastors point to youth sports as a main cause for families to skip church on Sundays.

I know that comparing football to Madden isn’t a perfect analogy. But they share enough commonalities that Brad could learn from what Ross was doing.

Redeeming Sports

“Athletics is a vehicle to helping you become a better servant of God and a better lover of mankind,” Ross told me.

Ross and his team believed that. So they wrote down four principles and called them the Defender Way. Basically, they want their student athletes to first be committed Christians, then servant leaders in their communities, then excellent students, and then winners of championships.

It’s not rocket science, just a written-down list of priorities. But it’s made a big difference.

Dordt coaches pray and lead devotions, but they also form discipleship groups with their teams. They talk about competition as worship. They’re serious about service, and athletes rake leaves and move boxes for community members. They’re also serious about academics, which means some teams meet during the season to plan their time so athletes can schedule in papers and study groups. It means coaches know in real time how their students are doing on assignments. Last year, for the first time, the 3.47 average GPA of Dordt’s student athletes was higher than the average GPA of the general population.

A few years ago, Dordt hired a football coach with a master’s in theology from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. I was intrigued—first, because I love it when coaches go to seminary. But also because Joel Penner is tasked with training young men to be adult men. I asked him if that was harder than it used to be.

“I’m looking over 22 years, even back to when I was a high school and college athlete,” Joel said. “I don’t ever remember feeling like my aggression, or my competitiveness, was wrong. And I think that’s one of the biggest shifts now in culture. We are—I hate to say castrating men, because that sounds bold, but maybe that’s appropriate. Culture is funneling men into a really confusing predicament. Your aggressive and your competitive impulses are part of your depravity—I think that’s the message.”

Joel is all for testosterone and aggressive play, as long as it’s self-controlled.

“One of the things I love about football is the way that it teaches discipline,” he said. “Self-control is a fruit of the Spirit. And imagine the self-control it takes to put four to six seconds of absolute passionate, competitive, aggressive energy into a play—to block, tackle, run, throw, catch, take somebody down. You get four to six seconds. Then the whistle blows, and it’s over. I mean, it’s not just slowly over. The whistle blows—stop. And then guess what? You do that 60 to 80 times a game. Think of it like a light switch—on, off, on, off—with this full aggression. The training for self-control is remarkable.”

It strikes me that this isn’t just true for football. It’s also true for basketball, baseball, soccer—every sport features aggressive play within boundaries. Honestly, so does war. In general, even when the fighting is fierce, neither side wants to hit hospitals or civilians. When they do, the other side—and the watching world—cries foul.

Those same principles hold true for video games. You can play wild and angry, or you can play with focus and control. You can play for a limited number of minutes, or you can let video games take away your sleep or meals or family time.

And then Joel gives me the money quote, which breaks it all open for me.

Lion and the Lamb

“God gave us two very helpful images when we’re to think about Jesus,” he said. “We have a lion, and we have a lamb. For millennia now, Christians have been picking which one better fits their narrative. You don’t get to do that. You have to understand—he’s both. We would be better served if we opened up to this idea that Christians—not just men, but for sure men—need to model his behavior. He’s a warrior. And he’s a prince of peace.”

I can’t stop thinking about this. “Stop being so weak,” our culture told men 50 years ago. Now they’re hearing, “Stop being so strong.”

It’s hard to know what to do, how to be.

But nobody looks at an athlete and thinks he’s confused or has a split personality for being both aggressive and submissive. Those two things work together to create something so lovely we pay to watch him do it.

If we’re following Jesus, we should look like that too. An all-in, full-blown, fierce rush onto the field God has set before us—all our energy bent into the work. And at the same time, complete submission to God’s will, his Word, his leadership of us. We are fierce warriors under a captain, brilliant scholars under a teacher, faithful and able servants under a king.

That’s beautiful.

But I’ll tell you what’s even more beautiful—to hear that come out of the mouth of a college football player.

“Like the dual nature of Christ, he was the Lion and the Lamb,” offensive lineman Alex Huisman said. “He was humble man, but he was also a dominant man. So approaching your life, there’s that stance of reverence, but also that determination. It is not conflicting. It’s something that is in line with who you are, who you’re called to be.”

So how can you pull that same idea from the football field to the game room?

From the Football Field to the Game Room

Brad got to work, experimenting with ways video games could help students better love God, be servant leaders, and be good students. He started a class called “Engaging the World of Gaming.” In it, he talked about the history of video games, including Christian developers. He talked about God’s sovereignty over every aspect of creation. And he talked about sin.

Here’s one interesting question Brad asks his students: Can you sin in a video game? He means, Can your avatar sin? When you kill a noncombatant or hoard wealth or fight for your own glory, are you doing that? What is that doing to your soul? Do you need to repent?

And anyway, what does it mean to be a Christian avatar? Could someone else, by watching you play, see something different about you? If they asked, could you share Christ with them?

Brad would love to explore, and then offer, an organized approach to video game missiology.

“We would love to have gaming ethnographers to be able to go and, as if we’re going to a different tribe, to watch and observe and compile data so that we can be online missionaries,” Brad said.

That’s a huge mission field – 3.24 billion people.

“We want it to be the sort of education where we’re training [students] and preparing them well, to go into these spaces to be able to do as this coram Deo gaming,” he said.

‘Coram Deo’ Gaming

Gaming coram Deo—before the face of God.

Brad decided to start a gaming club to help students live within limits online for God’s glory. To begin, he created an application process, convinced that putting up boundaries lets students know they’re on a team and they’re living under authority.

Then he limited the game selection. Dordt’s club has no glorification of any exploitation, no games where it’s hard to find a redeeming quality. The gamers use top-of-the-line equipment in a basement room with lots of space and cool lighting. But it isn’t open all the time.

“The hours that it’s available are probably far less than what anyone would ever guess,” Robert said. “We’re cutting people off, so they get good sleep at night, or at least we’re not in the way of them getting good sleep. We’re making sure that we’re not in the prime study times of the day, distracting students from their studies. We’re having a lot of our big events on weekends, but not filling up both weekend nights, because we’re also hopeful that while they’re engaging in the guild community, we’re hoping that through all of this process that they’re also engaging in the rest of the community too.”

Brad built a leadership structure for the gaming club, with a president and vice presidents. Dordt added even more accountability—if a member of the club starts skipping class or missing too many assignments, the professors can contact Brad who, like an athletic coach, has the authority to talk with a student about her behavior. If it continues, or if her GPA dips too low, she can lose her club membership.

By the time Brad finished, the video game club was so far from an esports program he had to change the name. Instead, he called it a gaming guild.

That might seem like a lamer version of an esports team. But when they opened the guild last year, 54 students signed up even before the official launch. Soon, numbers jumped to 80, then rose to 96 this year, with another 20 on the email list. On a campus that houses just over 1,300, that’s about 9 percent of the student population.

“It’s been a lot of fun,” Johnny said. “It’s nice to just be a part of something like this, getting to build something. Most of the effects that I see on the campus as a whole happen in the events that we do on Fridays. We’ll have a bunch of people playing Smash Bros.—we had Smash Bros. tournament earlier this semester. We have tons of board games that people can get together and play. And then sometimes we’ll just have, like, five people on all the computers playing on a competitive match together as a team. And it’s so much fun.”

“Before the guild, guys would just video game in their apartment,” Kayla said. “And I think one of the biggest benefits is that now this is reaching a whole new audience of people—guys and girls alike—who didn’t necessarily feel like they had a home or somewhere they could just be themselves. And now they have that outlet. And they have that space to be themselves and to do something that they love.”

Kayla dates Johnny now, and she appreciates the way he’s working at setting boundaries to prioritize his schoolwork. She plays too, for the sheer joy of it. She loves the VR headset that lets her slash beats of music as they fly through the air. To her, it feels like directing. She also enjoys role-playing games, which let her pretend to be a character for an hour or two.

Carolyn, who is a senior music major, loves that too. Here’s her favorite thing about the guild:

It’s a huge community, and there are so many different games that the guild has that you can play. So there’s something for everyone. It’s really casual. You just come and there’s food and there’s games, build friendships. It’s a really great outlet for like people like me who wanted to get into something but didn’t really know how. . . . I think there are quite a few people that I don’t think I would have met if I didn’t go to the gaming guild stuff. Or maybe I knew who they were, but I didn’t talk to them.

“Perhaps one of the most meaningful developments for me personally is to have watched students grow and mature,” Brad said. “For example, I’ve seen students such as Abigail and Bri and Jacob Toole, who I think were quite hesitant to buy in initially, and who I now see at every event. They’re laughing, they’re part of deepening and maturing friendships, and it’s all so wonderful to see. Even my guild president, Ethan—growing, maturing, learning how to lead, host events, and be there for the members of the guild. It’s all so deeply satisfying as the guild director.”

Maybe you’re noticing that Brad and the students aren’t talking about how much they love the equipment, or the internet connection, or the cool basement space—though they tell me they like those things too.

What they love most is being together.

“As I’ve had a chance to go to their activities, I see beautiful health,” Robert said. “And I see so many people that I know without the guild would be in their rooms at that very moment by themselves on a Friday night. Instead, I hear laughter, I hear conversation, I hear teasing one another. And I see people together. It’s so beautiful. Because you know what the exact opposite of that always was. That’s what’s so exciting about it. It just feels like we can’t take credit for this. The Holy Spirit’s doing something here. And we get to be a part of it. And that’s so exciting.”

Wisdom and Grace

I don’t want to leave you with the impression Dordt is doing things perfectly. While lots of kids come to the gaming events, some are still in their rooms, gaming alone. And there are still tons of questions to be asked and answered about a Reformed view of video games.

But I can feel myself shifting on this. Maybe video games could be a way to relax into delighting in the goodness of God, the creativity he gave a game designer, and the joy of connecting with people who are physically far from us. Maybe they could help boys be aggressive within limits, a way to point to and practice living under Christ’s headship.

That said, I’m wondering if I need my own version of the Defender Way—rules of life to give perspective and limits to both youth sports and online gaming. More than anything, I want my boys to love God and neighbor. I want them to serve joyfully, to work diligently, to submit humbly to authority.

To that end, I want to challenge them to be Christ-followers at school and at home, on the court and on the screen. But I also want to push a little further, to ask, “Do sports or video games cause you to stumble into sin in real life?”

To be honest, I have a kid who was struggling with video games. When he was playing, he was easily frustrated. When he wasn’t playing, he was thinking and talking a lot about when and what he was going to play next. He complained when we told him to turn off the game. And he was never more patient, kind, or joyful when he was done.

So a few months ago, we turned them off altogether.

For this kid, that was exactly the right move.

Since then, he’s built his own go-kart with wood and wheels. We got him a bow and arrow, and he shoots cardboard targets in the backyard. He roller blades and runs and reads and built a website where you can look at pictures of his go-kart. He’s more interested in conversation, more eager to help empty the dishwasher or set the table. His spirit seems more joyful, more gentle, more patient.

I’m not telling you this so you’ll throw away all your—or your kids’—video games. That might not be the right choice for you. But I do want to encourage you to pay attention. Ask yourself, your friends, your spouse, your kids the hard questions.

The video game industry needs Christian thinkers who can figure out how to game coram Deo.

There are three aspects to that, Brad said. “First, the joy of it—if you’re not doing it in joy and delight and honor for God, then you’re not going to do a good job. Second, if you don’t do with responsibility, it’s just going to be secular. And third, there is the historic part of asking how we take into account the voices of the past. We want to allow the voices of the past to speak, whether it’s Kuyper, or whether it’s gaming designers, because there are a lot of people that have been Christians who have paved the way for gaming.”

Young men—and women—if video games delight you, draw your soul to worship God, or genuinely connect you with others, lean into that. Be the type of player who asks how someone is doing, who make choices with noticeable integrity, who plays in a manner worthy of the gospel of Christ. Model the beautiful paradox of Christianity—be the player who conquers new worlds and wins strategic battles but who also can cheerfully log off to eat dinner with your family or put away laundry or finish your work.

And as you look for worlds to conquer and enemies to vanquish, remember this—that character you are online is nowhere near as smart or complex or gritty as the real you. The world you enter online can’t come close to the breathtaking, exhilarating world God has created for you to explore in real life. The digital adventures you have aren’t as exciting, the enemies you face aren’t as formidable, the opportunities aren’t as incredible, the twists aren’t as unexpected, the stakes aren’t as high, the friendships aren’t as fun or as tight as those in your real life.

Let’s play games—just like we strive to do everything else—under the lordship of Christ and before the face of God.

Is there enough evidence for us to believe the Gospels?

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.

In an age of faith deconstruction and skepticism about the Bible’s authority, it’s common to hear claims that the Gospels are unreliable propaganda. And if the Gospels are shown to be historically unreliable, the whole foundation of Christianity begins to crumble.