You’d be hard pressed to find anyone more Anglican than David Short—which just made everything worse.

The 61-year-old is a fourth-generation Anglican minister, born in Africa while his parents were missionaries. He can even top that—his father was also born in Africa to missionary parents.

Home was Sydney, Australia, where he found the Anglican diocese “robustly evangelical, missionary in its heart, and deeply thoughtful on many issues.” Short went to high school there, then university. He went back for more theology courses, then got ordained. He wrote his master’s thesis for theologian J. I. Packer at Regent College, then became Packer’s pastor.

Short loved Jesus, loved Reformed theology, loved Anglicanism. And then he took a job in Canada.

“I’d never met a liberal Anglican until I came to Vancouver,” he said. “I was thrust into the most strange, dysfunctional, liberal diocese.”

In 2002, when his regional synod voted to let its bishop bless same-sex unions, Short stood up and walked out of the room (as did Packer). So did leaders from half a dozen other churches.

The pastors knew they had to form their own organization and to find episcopal supervision. But that didn’t seem hard. Most of the global Anglican church still held to the gospel. The Canadians just had to appeal for alternative episcopal oversight, something already permissible in Canada, and call it a day.

“I thought it would take 10 weeks,” Short said.

It took 10 years. Ten years of accusations and meetings and lawsuits. Ten years of stress and fear and anger. Nearly all the churches would lose their buildings; all did lose congregants and money. Pastors lost sleep. Some nearly lost their sanity.

“We asked all the wisest people I knew—all the cleverest theologians,” Short said. “No one had any idea what to do.” So they just did the next thing. And the next.

This June, the Anglican Church in North America—made up of break-away conservative Anglicans primarily in the United States and Canada, including Short—will celebrate its 10th anniversary. The denomination has 135,000 members in more than 1,000 churches. It’s in “full communion” with the Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans (GAFCON).

“It was all worth it,” said Ottawa rector—the Anglican term for senior pastor—George Sinclair, whose church left with Short’s. But he would have said that no matter what.

“Even if the church had declined, that wouldn’t be a sign that we had made a mistake,” he said. “Because the Bible is clear on this issue. You need to take a stand on it—without any expectation about how God will bear fruit from your faithfulness.”

The Church of England in Canada

The Anglican church—which was founded on Reformed theology—immigrated to Canada with the British. In fact, not until 1955 was the name changed from the “Church of England in Canada” to the “Anglican Church of Canada” (ACC). (Canada itself wouldn’t be fully independent until 1982.)

The denomination did fairly well—by 1964, there were 1.37 million “total souls on parish rolls.” That was about 7 percent of Canada’s population—for comparison, Southern Baptists today make up about 5 percent of the U.S. populace.

But that was the Anglican high-water mark. In 1967, the “total souls” in the ACC had dropped to 1.2 million. By 1997, it was 717,000. By 2007, 546,000. After that, the leadership quit releasing numbers, though some estimate the decline at 13,000 a year.

In 1999, American Episcopal bishop John Shelby Spong wrote Why Christianity Must Change or Die in a bid to “formulate a Christianity for the postmodern age,” where claims like the virgin birth, resurrection, and biblical infallibility have “long since been challenged and discarded by science and philosophy.”

It was an attempt to stop the bleeding, and many agreed with him. Short remembers synod gatherings where “we’d sing hymns from Hindu scriptures, pray to the ‘god of many faces,’ and annually support the women’s spirituality dialogue that taught women to channel spirits.” Short’s bishop, Michael Ingham, wrote a book titled Mansions of the Spirit: The Gospel in a Multi-Faith World, which “challenge[d] the Christian notion that Jesus is the only way to God,” Short said.

But not all Anglicans believed Christianity had to change to stay alive. In 1994, a small coalition endorsed the Montreal Declaration, which affirmed ideas such as the virgin birth, the authority of the Bible, and marriage between one man and one woman. The signers became the Essentials Council—a place where conservative Anglican pastors could find each other.

Thankfully, not all Anglicans believed Christianity had to change to stay alive.

Unfortunately, the Essentialists were on an impossible trajectory, wedged between their own convictions (validated by the growing conservatism of global Anglicanism—especially in Africa and Asia) and the mounting liberalism of their Canadian “province” (the Anglican word for region).

“We always had an awareness that there was a liberalism within the Anglican Church of Canada in practice,” said rector Ray David Glenn, who remembers not taking communion during a diocesan service “laden with secular, pagan, and Wiccan symbolism.”

The problem arose “when it became formalized in doctrine,” he said. For him, “that was the tipping point.”

Formalized Heresy

In 1998, after an emotional, three-hour debate at the decennial Lambeth Conference, the global Anglican bishops approved—by a count of 526 to 70—a resolution upholding the historic, universal biblical teaching on sexuality and opposing the recognition of same-sex unions. The strongest language came from conservative pastors in Africa and Asia.

The resolution was clear, but it wasn’t binding. Four years later, Short’s diocese of New Westminster—a regional body within the larger Canadian province of the Anglican Church—became the first to allow the blessing of same-sex marriages.

After the tally was announced—63 percent in favor—some Essentialist pastors stood in protest. Others—including Short, Packer, and representatives from eight other churches—stood and walked right out of the room.

“There were tears,” Short remembers. “It was really difficult.”

The dissenters didn’t have much strength in numbers—they represented just nine of the diocese’s 80 parishes. But they did contribute almost 25 percent of the income, and many began withholding it immediately. (In retaliation, Ingham stopped paying some pastors’ salaries.)

“My reaction is shock,” rector Trevor Walters, who walked out with Short, told reporters then. “If you were going to write the worst possible outcome, this would be it.”

In some ways, that was true.

The Worst

“The very next day we got threats from the bishop,” Short said. “He brought charges against me and the other clergy. We all had to go and see him, and the [denominational lawyer] demanded that we promise our obedience to the bishop.”

“I will obey you in every lawful command,” Short told him. “Lawful means biblical. What you’re doing is unbiblical.”

Ingham leaned hard on him, but Short didn’t change his mind.

“At that point I didn’t know if it had torn the fabric of the communion, but I knew it was a salvation issue,” Short told TGC. “What helped me was reading the Reformers again, particularly Calvin’s Institutes. He speaks a lot about not breaking away, and then breaking away when corruption enters the citadel of the church. That’s what happened.”

“Functionally, we found ourselves part of a national church that was no longer recognizably Anglican historically or globally,” Glenn said. “They were using Christian language to describe secular humanism.”

Short didn’t change his mind when the alternative oversight offered by another Canadian diocese was withdrawn after threats of investigation and discipline. He didn’t change his mind when Ingham filed charges to revoke his license and nullify his ordination—and Packer’s—over the rift. He didn’t change his mind when a gay-rights activist joined his church in order to protest it. And he didn’t change his mind when the death threat came.

“I can’t tell you the horror with which we were regarded,” he said. “We were on the front page of the paper. People I knew crossed the street to avoid me. My wife, in a store, overheard people talking about the ‘wickedness’ of ‘that David Short.’”

The crisis was heavy for all of the pastors who left—they were suspended without pay, lambasted in the press, abandoned by some of their friends and congregants. But worst of all was the prolonged tension.

“The stress went on for a long time,” said Sinclair, whose church left the ACC three days after Short’s. From the time of the New Westminster vote to the launch of the conservative Anglican Network in Canada (ANiC), six years had passed. By then, “the Anglican clergy in Ottawa had already been talking about same-sex blessings for a good 10 years.”

When the break came, the stress didn’t stop.

“No parish or congregation . . . has any legal existence except as part of the diocese,” Ingham wrote. “[A]ny attempt by any person to remove a parish from the jurisdiction of the Bishop and Synod would be schismatic.”

The leaving churches objected, arguing that the ACC had abandoned Anglicanism. Lawsuits and counter-lawsuits and counter-counter-lawsuits popped up in the courts.

“When we voted to separate from the ACC, we knew we would probably lose our property and assets,” Sinclair said. “Our legal issues lasted over three years and ended with an out-of-court settlement where we walked away from our property on the condition that the one other church in town that also left would be able to keep their building.”

“The diocese sued us, officially and personally,” Glenn said. “We ended up moving into a temporary space. It was supposed to be six months but turned out to be eight years.”

The pressure was perhaps heaviest on Short, who was at the center of the rift. With a congregation of 2,000 members—around 1,000 of them weekly attendees—St. John’s was the largest Anglican church in Canada. For nine years, Short spent two to three days of every week on the controversy—reading and writing legal documents, meeting with leaders across the globe, and seeking agreement among orthodox congregations.

And then it was too heavy. He remembers the weekend it all fell apart—his wife’s mother died, he officiated a “difficult” wedding, and the church hosted two outreach events.

“I remember lying on the grass outside, in tears, feeling the world was spinning away from me,” he said. On Monday he saw his doctor, who gave him an anxiety/depression test. “If you’re above 16 [on the test], you’re in trouble,” Short said. “I was at 21.”

His doctor told him to quit working immediately. Short thought of the preaching conference he was scheduled to be at in Washington, the trip to Europe, the two conferences he had committed to for conservative Anglican evangelist Rico Tice in England.

“I couldn’t do any of it,” he said. “I had a full-blown breakdown.”

It would be 30 months before he was back to work full-time.

“I never doubted the Lord’s love,” he said, “but sometimes the Lord takes you aside from regular stuff to help you see you can only rely on him.”

Unity in Division

“One of the hardest leadership things for me was when, a year and a half after leaving our building, the congregation began to shrink, reaching about half our former size,” said Sinclair, whose membership at St. Alban’s dropped from about 220 to 110 during the crisis. “I spent a lot of time agonizing with God if I was unfaithful or my preaching had deteriorated. But I came to the realization that people weren’t going back to the Anglican church—they were going to Presbyterian or Baptist churches because they wanted a building.”

That took the sting out.

So did the fact that the church “never missed paying a bill.” And that “the morale of the congregation never faltered, even when people were leaving.”

Over at St. George’s, the first Sunday spent in its temporary space was “profoundly joyful,” Glenn said. “There was no sense of mourning or sadness. I remember saying to my wife, ‘If this is suffering for the gospel, sign me up.’”

His people had voted 98.5 percent in favor of leaving the denomination. On the other side of the country—44 hours away—Short’s had approved leaving by 99 percent.

The unity was oddly high—after all, leaving meant taking a reputational hit, paying out significant money to attorneys and court fees, and eventually losing their historic buildings. Who’s signing up for that?

Voting to Follow Jesus

Well, not everyone signed up for that.

“We lost people in the early months—people who couldn’t stomach engaging with this thing and more people who were committed to a cultural view of the gospel on this issue,” Short said. “A lot of people had to make painful decisions where they had to nail colors to a mast on a culturally unpopular issue.”

He held “town hall meetings” to answer questions about what was happening but determined “I’d never preach about the crisis in the gathering” because “that was for teaching the Scripture and the worship of God.”

That was a common—and, it turned out, critical—decision among conservative pastors.

Glenn explained the conflict to St. George’s and held prayer meetings. But on Sundays, he preached the Bible.

“We didn’t preach toward leaving our diocese,” he said. “We just preached the gospel. I remember the last series we preached was through Galatians. When we started preaching through books of the Bible, it became so abundantly clear this is what had to happen.”

Sinclair was “imposed” on his urban, liberal church “against its will” back in 1995. “Over time as I started to preach, some people left quietly and some left with great announcements,” he said. “But a few people got converted, and the Lord started to draw other people there.”

When they eventually voted, 13 years after he arrived, the count was 99 percent in favor of leaving the ACC. And when the time came to decide whether to vacate their building or ask the other church in town to vacate theirs, not a single person voted to stay.

Anglican Network in Canada

The New Westminster vote was the first shot in a much larger battle, and more quickly followed. In 2003, a practicing gay man became a candidate for bishop in England (he eventually withdrew his name); another became a candidate for bishop in the United States (he succeeded).

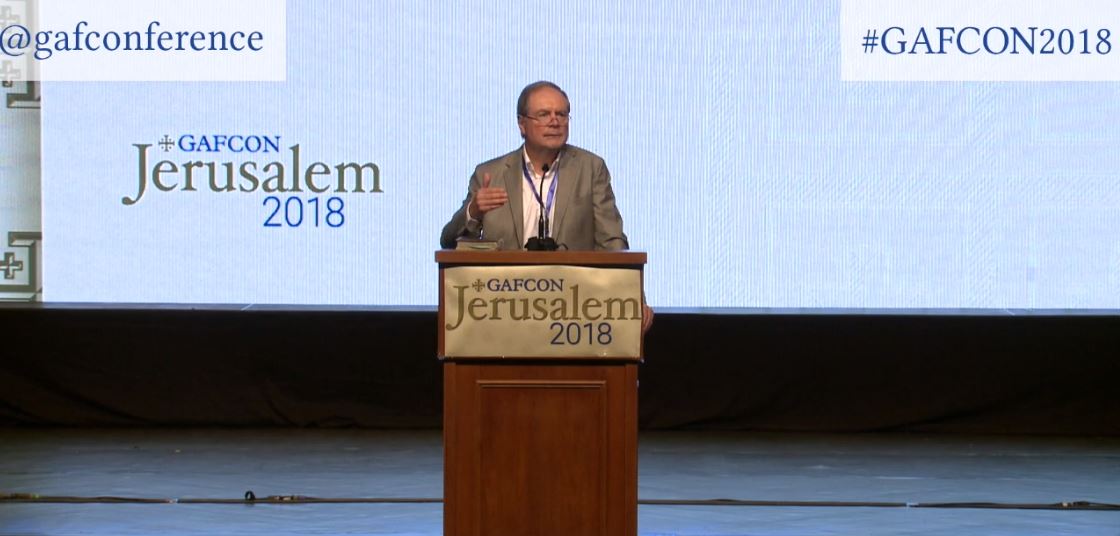

In response, about a quarter of the world’s bishops boycotted the 2008 Lambeth Conference, where liberal American and Canadian leaders were allowed to attend but not vote. Then those African and South American bishops launched a conservative conference of their own. GAFCON was meant to be a “one-time event” but instead birthed a council that today represents “50 million of the 70 million active Anglicans of the Communion.” (GAFCON, which originally stood for Global Anglican Future Conference, now refers to the whole movement.)

“One of the most marvelous things that has happened is the great strength in the Global South has gathered around the GAFCON conference,” Short said. “The stories from around the world are remarkable. The Lord is doing something in global Anglicanism.”

In Britain, where the denomination started, the Church of England restricts marriage to a man and a woman, but some pastors unofficially bless same-sex partnerships in marriage-like ceremonies. In December, the denomination recommended—but didn’t require—that those wishing to mark gender transitions use the baptism service liturgy. And the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby invited same-sex bishops—but not their partners—to the once-a-decade Lambeth Conference in 2020.

Overall, it’s “an unprecedented global realignment of Anglicanism,” Glenn said.

In Canada, post-split, there’s a sort of peace.

This July, the ACC will vote on the second reading of an amendment that would allow same-sex marriages, making it church law.

Meanwhile, the ANiC—which is now a diocese of the 10-year-old Anglican Church in North America—spells out that “marriage, by its nature, is a permanent and lifelong union, for better or for worse, til death do they part, of one man with one woman, to the exclusion of all others.”

The ANiC had 74 churches at the last official counting in 2017. Membership had grown from about 7,200 in 2015 to 7,800 in 2017.

“It was like surgery,” Glenn said. “It cost us a lot of time and energy and money and buildings, but it was trauma that was toward a greater health.”

Before, the diocese was “held together by institutional measures,” he said. Now, “we actually have a sense of affinity and brotherhood.”

At Sinclair’s church, which is about to launch its first church plant, attendance is up from 110 to 140. Short’s church has been able to plant “a couple of churches” and remain around 700 weekly attendees. Glenn’s congregation has grown from 100 to 250 weekly attendees.

“We’re baptizing 16 candidates on Sunday—we do baptisms every quarter,” he said. The number “isn’t abnormal for us. What is abnormal is to have Anglican congregations where adults are being converted to Christ.” (Since the mid-1960s, the four largest mainline denominations in Canada—including the ACC—have lost half of their members.)

On any given Sunday, less than 10 percent of the people in his pews would even know what the “inside of our old church building looked like.”

Worth It?

Sinclair laughs when he remembers joking years ago with then-rector Charlie Masters, “Maybe we’ll end up running into each other at a Christian and Missionary Alliance convention in a couple of years as pastors there!”

Then more soberly, “because Anglicanism isn’t worth losing your soul over.”

In our culture, sexuality “the issue that rubs up against the gospel,” Glenn said. “Apart from the gospel, a pastor is nothing but an underqualified social worker. The gospel is all we have.”

If you’ve been preaching to a congregation for a few years but don’t know if they’d vote to leave the denomination over a gospel issue, that should be a “gut check,” Sinclair said. “Obviously, you want to convince them of the wisdom of these doctrines. You don’t want to be ham-fisted. But I wonder how many pastors and churches don’t take stands for fear of offending.”

Apart from the gospel, a pastor is nothing but an underqualified social worker. The gospel is all we have.

He remembers watching one of his members bring a non-Christian friend to a service.

“As he walked in, I knew that I was going to be preaching on sexuality,” Sinclair said. “I confess I thought it was too bad the sermon was not on something else, but I preached on sexuality anyway.” Later, the man’s friend told him that instead of being offended, he found it interesting. (“Non-Christians know Christians believe something different from them.”)

Sinclair also remembers preaching about Christ’s propitiatory death on the cross and “getting a handful of letters denouncing me and a handful of people at the door saying, ‘That’s the most beautiful thing I ever heard in my life.’”

“You don’t know how God is going to provide for you or use you to be fruitful,” Sinclair said. But that doesn’t mean God owes you fruit.

“A lot of despair comes from clergy who secretly believe God should bless them because they’ve taken a stand,” he said. “I had bits and pieces of that in me. But that’s a deep spiritual poison for a Christian or a minister.”

Instead, “you need to take a stand without any expectation about how God will bear fruit from your faithfulness.”

A lot of despair comes from clergy who secretly believe God should bless them because they’ve taken a stand. . . . But that’s a deep spiritual poison for a Christian or a minister.

Short doesn’t even like the question, “Was it worth it?” (Both Sinclair and Glenn say it was.)

“I think that’s a Satan question,” he said. “If you’re a faithful Christian, you can’t go ahead with the blessing of same-sex marriages. You can’t join fully into that by giving money [to that denomination]. So what do you do?”

Maybe you stay in the denomination and advocate for biblical truth. Or maybe you walk out of the meeting. Maybe you file the lawsuit or fight one that’s been filed against you. Maybe you form a brand-new denomination.

You do the next thing, “being faithful with what God has put in front of you,” he said. And the whole time, you preach the gospel.”

Why Do So Many Young People Lose Their Faith at College?

It’s often because they’re just not ready. They may have grown up in solid Christian homes, been taught the Bible from a young age, and become faithful members of their church youth groups. But are they prepared intellectually?

It’s often because they’re just not ready. They may have grown up in solid Christian homes, been taught the Bible from a young age, and become faithful members of their church youth groups. But are they prepared intellectually?

New Testament professor Michael Kruger is no stranger to the assault on faith that most young people face when they enter higher education, having experienced an intense period of doubt in his freshman year. In Surviving Religion 101, he draws on years of experience as a biblical scholar to address common objections to the Christian faith: the exclusivity of Christianity, Christian intolerance, homosexuality, hell, the problem of evil, science, miracles, and the Bible’s reliability.

TGC is delighted to offer the ebook version for FREE for a limited time only. It will equip you to engage secular challenges with intellectual honesty, compassion, and confidence—and ultimately graduate college with your faith intact.