“Inevitably the question arises whether the opinions of such men [the authors of the Bible] can ever be normative for men of the present day,” J. Gresham Machen wrote in Christianity & Liberalism. Machen’s book came out in 1923, in the period when a conservative movement sprung up within Protestantism in reaction to liberal theology and the form of biblical interpretation known as higher criticism. This movement, known as “liberalism” or “modernism” was considered one of the greatest threats to biblical orthodoxy and provoked a commensurate response.

Between 1910 and 1915, a series of 90 different articles by 66 authors was collected into a twelve-volume work called The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth. The essays mostly outlined the key doctrines—the “fundamentals”—of the Christian faith, such as the virgin birth of Jesus, the deity of Christ, and the inspiration of the Bible. But it also included such seemingly “secondary” issues as “The Church and Socialism” and “Evolutionism in the Pulpit.”

The term “fundamentalist” was coined in 1920 by the editor of a Baptist newspaper, who wrote, “We suggest that those who still cling to the great fundamentals and who mean to do battle royal for the fundamentals shall be called ‘Fundamentalists.’” Since then the term has taken on a different connotation, and even those today who “do battle royal for the fundamentals” would cringe at being called a fundamentalist (Machen himself didn’t like the term). But this fundamentalist-modernist split remains one of the key turning points in modern Christianity. As John Piper has said, “The spirit of Modernism is not a set of ideas but an atmosphere that shifts from time to time with what is useful.”

Now, a century later, we’re seeing how the “spirit of Modernism” is causing a similar split within Protestantism—and it’s dividing even the movement that sided with the original fundamentalists.

Evangelicals Embrace Sexual Apostasy

Few changes in church history have occurred as rapidly as the acceptance of homosexual behavior within evangelicalism. In 2011 only 13 percent of white evangelicals favored same-sex marriage. By 2016 support had doubled to 27 percent. But that number obscures the generational divide. While 23 percent of older evangelicals (born before 1981) favor same-sex marriage, the support rises to 45 percent for millennial evangelicals (born between 1981 and 1996). Additionally, more than half (51 percent) of young evangelicals say homosexuality should be accepted by society.

Hearing that more than half of young evangelicals are headed down the road to apostasy should give us a sense of historical déjà vu. While the affirming-sin position leads to apostasy, it is rarely if ever the first or only departure from orthodoxy. As with the mainline denominations, we’ll likely look back and wonder why the split within evangelicalism didn't happen sooner. We’ll discover the affirming camp had also begun to question the bodily resurrection, or dismissed the reality of hell, or concluded there must be more paths to salvation other than Christ. Ultimately, the root cause will be the same as it was 100 years ago: a rejection of both biblical authority and the historical consensus of the church about what Scripture says.

The original controversy was driven by what James Orr called an “attitude of negation to supernatural revelation, or to books which profess to convey such a revelation.” At the time, traditional biblical beliefs about the supernatural were considered to be superstitious and unscientific. Reasonable and intelligent people were expected to discard such outdated notions because they no longer fit with what modern society would tolerate. Today, traditional biblical beliefs about sexuality are considered hateful and unloving. And reasonable and intelligent people are similarly expected to discard those “outdated” notions about sex and marriage because the secular world says we must.

The result of the modernist-fundamentalist controversy was a split in almost every Protestant denomination. Some denominations, such as the Episcopal Church, leaned into the apostasy. Others, such as the Methodists and the Southern Baptists, fought for decades to hold the orthodox line. Most, though, followed the lead of the Presbyterians in breaking away into new denominations.

The orthodox expected the apostates to return (which rarely happened), while the modernists thought they could just wait for all the “fundamentalists” to die off (ironically, it was their own movement that has died and been resurrected as the “nones”). Looking back, the schisms seem to be so inevitable we may wonder why it took so long to finalize the divorce. Part of the reason for the protracted fight was because there were often real assets at stake—office buildings, college campuses, multi-million-dollar endowments. Choosing to remain orthodox meant you might lose your 280-year-old historic church property.

In contrast, modern evangelicalism is more decentralized and so the split is likely to occur rapidly. Today, a non-denominational megachurch can flip from orthodoxy to apostasy and never have to go to court to fight for control of their church building. It’s even easier to split when the assets are blogs, book deals, and mailing lists.

Unbridgeable Differences

A prime example of the new schimastics is ethicist David Gushee, who after forty years left evangelicalism because of the movement’s orthodox views on homosexuality. In an article promoting his new memoir, Still Christian: Following Jesus Out of American Evangelicalism, Gushee writes:

I now believe that incommensurable differences in understanding the very meaning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the interpretation of the Bible, and the sources and methods of moral discernment, separate many of us from our former brethren—and that it is best to name these differences clearly and without acrimony, on the way out the door.

I also believe that attempting to keep the dialogue going is mainly fruitless. The differences are unbridgeable. They are articulated daily in endless social media loops.

Gushee is correct that the differences are unbridgeable. As Andrew Walker says,

I appreciate Gushee’s candor and agree with him: The dividing line between those who align with biblical and historical teaching around sexual ethics and those who do not, is incommensurable. This is not a debate about eldership versus congregational authority, or internecine squabbles on how the end times will occur. This is about what the true church confesses. This is about truth and error. This is about eternal destiny. Christians who hold to the historical biblical position believe that affirming individuals in homosexual sin has the consequences of eternal separation (1 Cor. 6:9-11). We believe affirming sexual sin in this capacity eviscerates the clarity and intelligibility of God’s special and general revelation that sees humans purposefully sexed and complementary—tenets upon which the social order and cultural mandate are founded. We believe the disavowal of sexual otherness obscures the greatest reality in the cosmos—the Christ-Church union. Progressives who have jettisoned the historical position believe that denominations like my own, the Southern Baptist Convention, are doing harm not only to LGBT persons, but to the Spirit’s movement in the world. Those are the terms of this contrast and we should not paper over the disagreements in order to serve some false perception of unity in the name of fellowship.

In the 1920s, Machen expressed his hope that liberals would at least be honest that they wanted a new religion other than Christianity. What Machen wanted but never saw is already happening in our day, as affirming modernists have in many cases abandoned evangelical identity and institutions.

New Hope from an Old Controversy

As the fundamentalist-modernist controversy showed us, there can be no unity where orthodoxy has been abandoned. That’s why we should stop pretending we still share the same faith. We cannot be united when one side thinks that by not “affirming” homosexuality we are being hateful, and the other side believes it is hateful to lead people on the path to eternal damnation. For this reason, the evangelical movement will continue to split—it is as inevitable as it is lamentable. But it won’t be the end of orthodoxy in America.

We shouldn’t expect biblical views to be popular much less “normative for men of the present day.” As Jesus warned us, “the gate is narrow and the way is hard that leads to life, and those who find it are few” (Matt. 7:14). But while the truths of Scripture can be suppressed for a time, it’s impossible to eliminate them entirely. Not even the gates of hell can prevail against the church built by Jesus (Matt. 16:18).

Consider that in 1920, it seemed all but certain that most people who called themselves Christians would deny all of the supernatural aspects of the Bible. Yet today more than 70 percent of Americans believe in the existence of angels and heaven, and more than 60 percent believe in the existence of Satan and hell.

It may take another hundred years—or even a thousand—but God’s truth about sin and sexuality will once again prevail. In the meantime, we may find ourselves marginalized within society, within our churches, and even within our homes. But for “those who still cling to the great fundamentals” it’s a small price to pay for an issue of eternal consequence.

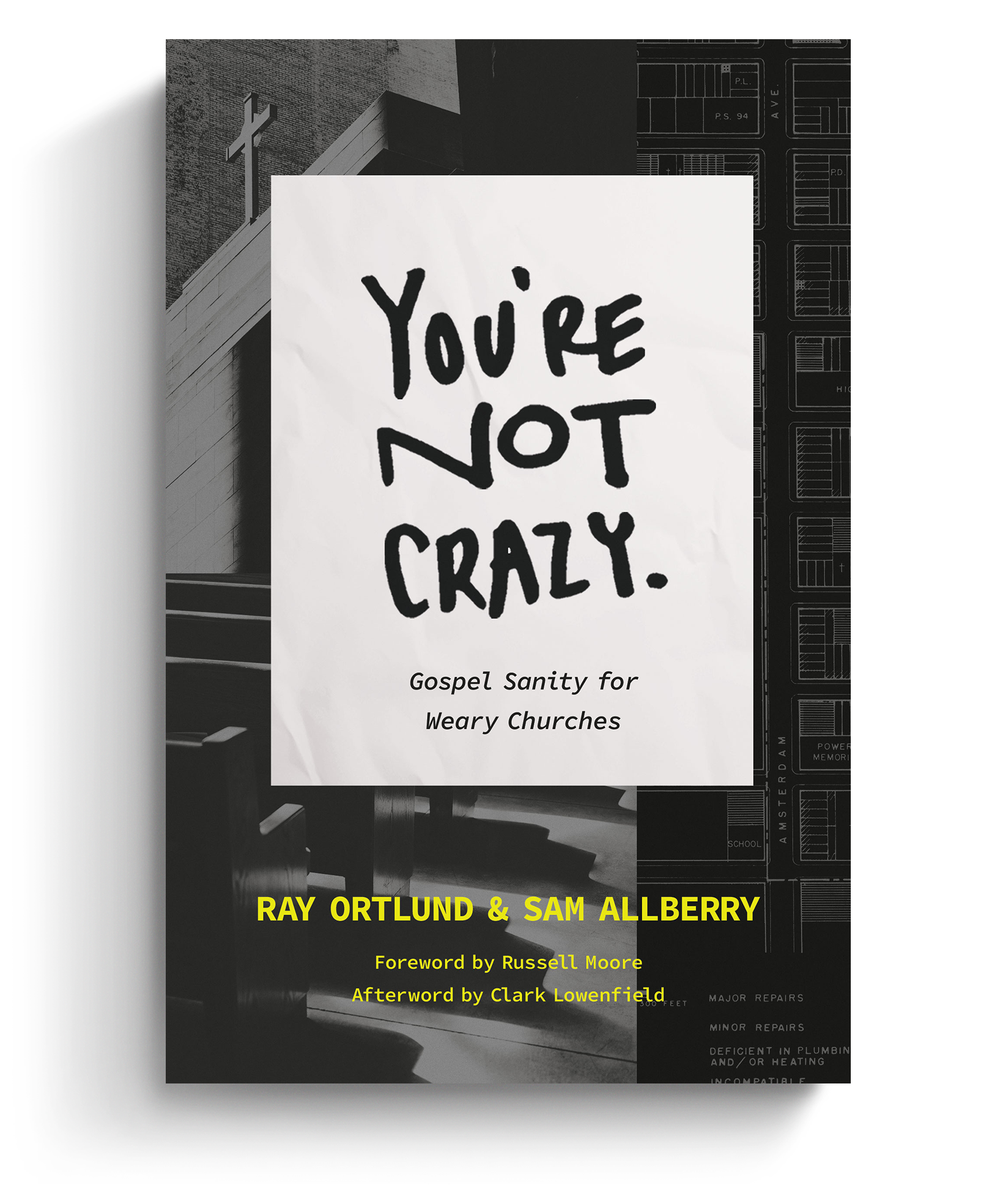

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.