You may recall that last year many Christians expressed deep concern with the popularity of Fifty Shades of Grey. The film’s graphic and abusive sexuality was decried as a spiritual and social outrage.

But while many in your church probably wouldn’t watch that film due to such extreme content, a newly released, funny, PG-13 summer romance should cause just as much discomfort.

What It’s About

Me Before You, directed by Thea Sharrock and based on a bestselling novel by Jojo Moyes, tells the story of the sweet-tempered and naïve Louisa (Emilia Clarke). She’s happy and unambitious, which turns out to be a problem when her family needs more income. Desperate for work, she becomes a full-time caretaker and companion for the disabled Will Traynor (Sam Claflin), a wealthy but embittered neighbor. Though Will cynically despises Louisa’s efforts at kindness, she determines to reach him.

Eventually Will’s guard lets down, and their friendship starts to bloom. But Louise soon discovers that Will wants a physician-assisted suicide; her employment was a last ditch effort by Will’s parents to change his mind. Louise decides that she must empower Will to experience the beauty and goodness of life. Soon the two are off on a series of adventures, during which the Laws of Cinema demand that Louise and Will fall in love.

What It’s Made Of

Much of Me Before You is cut from the cloth of conventional romance. We can predict, for example, that Louisa will dump her clueless and health-obsessed boyfriend (Matthew Lewis, whom Harry Potter fans will recognize as Neville Longbottom) for the sensitive and mysterious Will. Neither are we stunned when their first kiss happens before a picture-perfect skyline on an exotic beach.

Me Before You is clichéd, but it’s buoyed by Clarke’s delightful lead performance and a tender touch from director Sharrock. What’s more, the soundtrack overflows with that-summer-you-fell-in-love pop ballads, emotionally unencumbering a movie that’s mired in its fair share of pathos.

Where It Goes Wrong

So what’s the problem? Me Before You gets profoundly wrong the one thing it desperately wants to get right: the beauty and value of life. Will’s transformation affects his temperament only. Louisa finally receives his affection, but his true love remains his life before the accident.

In the film’s crucial scene, Will confesses to a tearful Louisa that he only wants to be the man he once was, not the man he is now. For Will, being unable to move means being unable to live.

“You’re being so selfish,” Louisa chides him through her tears. But she eventually accepts that he wants to die. She listens to her father, who tenderly counsels her that the only thing you can do for someone in the end is “love them.”

By the close of the film—spoiler alert—Will and Louisa reconcile, and she lies beside him as he orders his own death.

Why It Matters

Moyes, the novel’s author, acknowledges that she was motivated at least in part by her sympathy for patients who desire assisted suicide. “There are no right answers. It’s a completely individual thing,” she explained. “I hope what the story does, whether it’s the book or film, is make people think twice before judging other people’s choices.”

Clarke has likewise defended the film, insisting it shows a “situation” rather than an “opinion.”

Yet the film’s aesthetic clearly shapes its audience’s consciences. Sharrock portrays Will’s decision as inevitable, even brave. Lest we miss the point, the filmmakers offer a tight close-up of a woman who angrily criticizes assisted suicide as “no better than murder”—while wearing, rather prominently, a cross necklace. The imagery isn’t lost on the attentive viewer: These are the shrill and judgmental views of “the other side,” the side that cannot comprehend love.

Me Before You is a rom-com lacquered in layers of sinister irony, a love story that ends up celebrating autonomy instead of love, despair instead of hope.

At the beginning we see Will’s life before the accident. He wakes up next to his lover in an expensive apartment, before walking down the street conducting what is obviously Important Business on the phone. Later, Louisa stumbles on a video on Will’s laptop that shows him jumping off gorgeous seaside cliffs with friends.

This is the “life” Will demands and cannot live without. When he says “life,” he means fun and pleasure and success—and rather than challenge this notion, the main characters of Me Before You must learn to accept it.

But surely this perspective is moral disaster. Life cannot be measured by the function of our bodies, whether we can run, swim, make love, or even feed ourselves. Human dignity is grounded in the Creator whose image we bear and whose image cannot be destroyed by even the worst physical trauma.

In other words, reducing life to biological functions is not only foolish; it’s atheistic, denying the transcendent nature of God. Our lives don’t mean something because we have fully intact spinal cords or the normal number of chromosomes. They have meaning because God says so, a meaning that is clarified in the gospel, where God’s people are promised something better than an independent body: a glorified body. As Christians, we must share this truth repeatedly, whether we’re talking to those like Will with diabilities, to couples considering aborting their Down syndrome child, or to a “terminally depressed” patient weighing assisted suicide.

This is why the romance in Me Before You is so dangerous. It’s a tragedy that this film ostensibly about love can say nothing better to our culture of death than, “It’s his choice; deal with it.”

Whom It Affects

I watched Me Before You in a full theater, with as many teenagers as there were seniors. As time passed, I couldn’t help but wonder: Who’s in here, and what are their stories? I wondered if, among those who felt their heart moved, there were any teenage girls who had suffered sexual abuse and felt worthless, dirty, and disqualified from the love story they’d always wanted. I wondered if the 70-year-old man in front of me might think he’s a “burden” to his children and grandchildren, that everyone might be better off if it weren’t so, if he weren’t so.

Would Me Before You awaken these people to the value of their lives? Or would it affirm their suspicion that the life they see glamorized in culture—young, independent, carefree—is the only one worth having?

I left Me Before You sad. On the drive home, I imagined how many families would see previews for this no-nudity, no-violence summer flick and be drawn to its cheerful characters and heartfelt soundtrack. What would these folks do with Me Before You’s spiritually toxic portrait of people who hope, as the apostle Paul said, “in this life alone”?

Evangelicals can be quick to spot how the body is idolized in our culture through pornography. But do we miss it in our “family-friendly” romances?

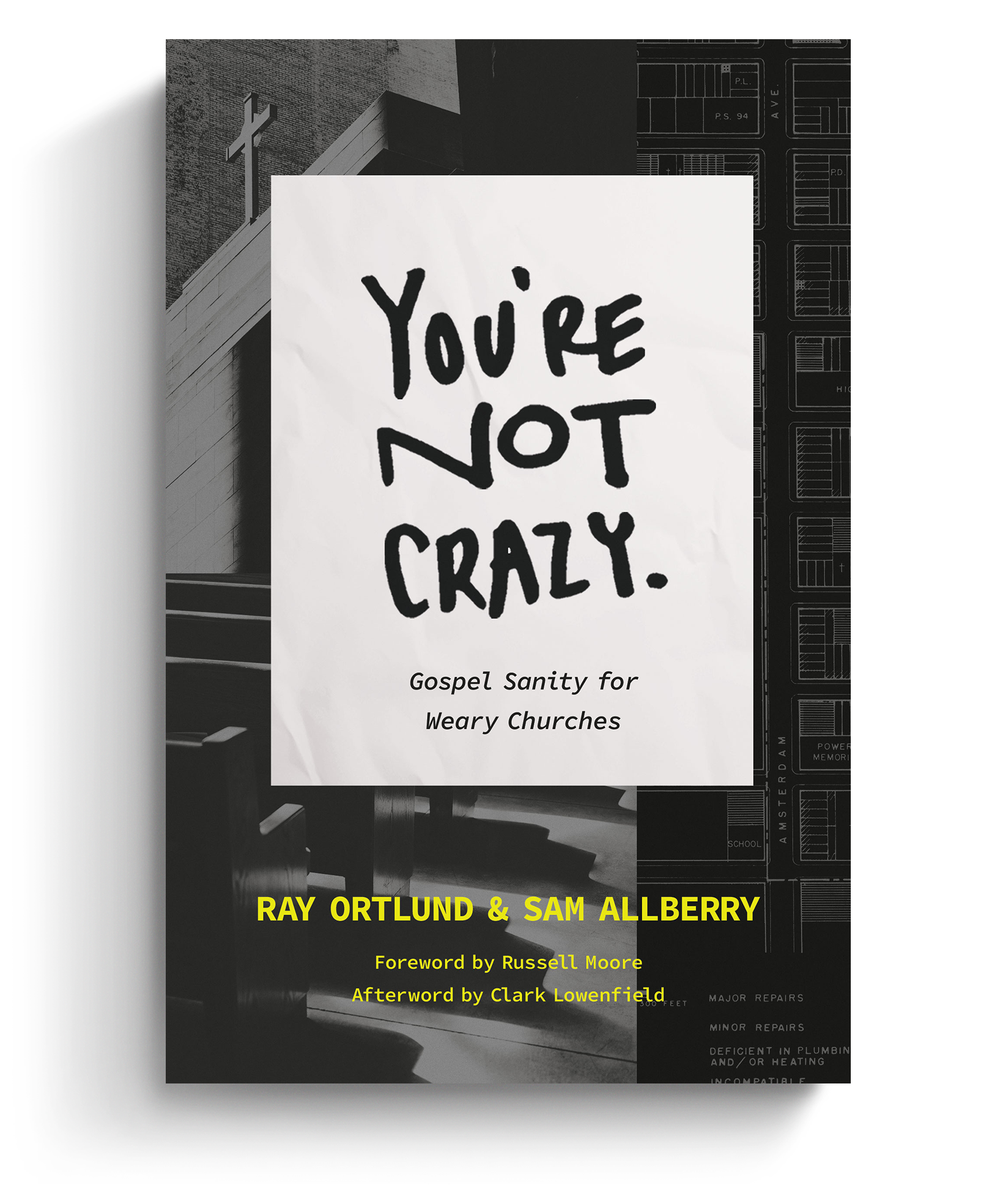

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.