Out of all the verses in the Hebrew Bible, the most frequently quoted in the New Testament is Psalm 110:1. But that’s not all. Verse 4 of the same psalm gets almost an entire chapter’s worth of commentary (Heb. 7:11–28). Clearly, the apostles and prophets saw this messianic psalm as highly significant for their understanding of Jesus.

We would do well, then, to consider how this psalm presents the Messiah whom we worship.

Messiah as David’s Lord and King (Ps. 110:1–3)

Like many other psalms, Psalm 110 is labeled “A Psalm of David.” But perhaps nowhere is David’s authorship more significant than here. It’s significant because David was Israel’s human king and “lord”—subject to Yahweh, of course. And yet here in verse 1, David refers to someone else as his “Lord”—someone distinct from Yahweh:

The LORD [Hebrew, Yahweh] says to my Lord [Hebrew, Adonai]:

“Sit at my right hand,

until I make your enemies your footstool.”

David, speaking in the Holy Spirit (Matt. 22:43), is overhearing a conversation. A conversation between two persons. The LORD we know. But who is this other Lord whom Yahweh invites to sit at his right hand? One whom even David refers to as “my Adonai”?

The apostles and prophets saw this messianic psalm as highly significant for their understanding of Jesus.

This is a passage Jesus used to stump the scribes and Pharisees (Matt. 22:41–46). They knew the Messiah would be David’s son. But then Jesus hit them with Psalm 110:1, asking, “If then David calls him Lord, how is he his son?” (Matt. 22:45). We now know the answer. Christ is both “the root and the descendent of David” (Rev. 22:16), “descended from David according to the flesh, and . . . declared to be the Son of God in power . . . by his resurrection from the dead” (Rom. 1:3–4).

But it didn’t end at the resurrection. The New Testament teaches that this invitation to “sit at Yahweh’s right hand” was fulfilled when Jesus ascended into heaven and sat down (1 Pet. 3:22; Heb. 1:3; 10:12; 12:2). As Peter argued on the day of Pentecost,

David did not ascend into the heavens, but he himself says,

“The Lord said to my Lord,

‘Sit at my right hand,

until I make your enemies your footstool.”’ (Acts 2:34–35)

From which he concludes, “Let all the house of Israel therefore know for certain that God has made him both Lord and Christ” (Acts 2:36).

That’s who Jesus is, according to Psalm 110. The ascended Lord and King seated on David’s throne (Luke 1:32; Acts 2:30), ruling “in the midst of his enemies” (Ps. 110:2) “until they are made his footstool” (cf. 1 Cor. 15:25).

Messiah as the Eternal High Priest (Ps. 110:4)

But Psalm 110 doesn’t just picture the Messiah as David’s Lord and King. It also presents him as our eternal high priest. We see this in verse 4, where David says:

The LORD has sworn

and will not change his mind,

“You are a priest forever

after the order of Melchizedek.”

Israel’s priesthood began with Aaron and was passed down through his descendants (from the tribe of Levi). When the monarchy arose a few centuries later, the monarchy and priesthood were kept separate. Nobody could be both king and priest. When King Uzziah tried to usurp priestly powers, God struck him with leprosy (2 Chron. 26:16–21).

But now David speaks of one who is both a king and also a priest. And for precedent, he reaches back to someone who predates the Levitical priesthood: the mysterious figure Melchizedek, who appears and disappears abruptly in Genesis 14 and is described as both “king of Salem” and “priest of God Most High” (v. 18).

A large part of Hebrews 7 is devoted to meditating on the implications of Psalm 110:4. Three points of significance are noted.

First, the timing. The fact that this psalm, written centuries after the advent of the Levitical priesthood, speaks of another priest arising from this pre-Levitical order, suggests that “perfection was not attainable through the Levitical priesthood” (Heb. 7:11). Otherwise why change the law by installing a priest from a different tribe (Heb. 7:12–14)? The order of Melchizedek thus doesn’t fit the later Levitical order, so if it’s coming back, Levi has to go.

Second, the word “swore.” “The LORD has sworn and will not change his mind, ‘You are a priest . . .’” The fact that Jesus was made priest “with an oath” puts him a notch above the Levitical priests, who were made priests “without an oath” (Heb. 7:20–22). A few paragraphs earlier, the Hebrew writer had noted that “when God desired to show more convincingly to the heirs of the promise the unchangeable character of his purpose, he guaranteed it with an oath” (Heb. 6:17). The same goes for Jesus’s priesthood. The fact that he was made a priest with an oath “makes [him] the guarantor of a better covenant” (Heb. 7:22).

Finally, the word “forever.” “You are a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek.” Once again, this is in contrast to the Levitical priesthood. Not only was the old-covenant priesthood as a whole temporary, but so was each priest. The reason they were “many in number” was because they were “prevented by death from continuing in office” (Heb. 7:23). But now “another priest has arisen in the likeness of Melchizedek, who has become a priest, not on the basis of a legal requirement concerning bodily descent, but by the power of an indestructible life” (Heb. 7:15–16).

This “indestructible life” is a reference to Jesus’s post-resurrection life, and is a reminder that Hebrews sees Jesus’s priesthood as something he prepared for on earth but exercises in heaven, where he “always lives to make intercession for us” (Heb. 7:25; cf. 5:7–10). This fits with what we see in Psalm 110, which begins with the priest-king being invited to sit at the LORD’s right hand in heaven.

Messianic Psalm Packed with Solid Food

Few psalms are as influential for New Testament writers; none is as often quoted. Just consider that every time you read of Jesus being “at the right hand of God,” you’re hearing an echo of Psalm 110:1 (Matt. 26:64; Mark 14:62; Luke 22:69; Acts 5:31; 7:55–56; Rom. 8:34; Eph. 1:20; Col. 3:1).

How much this psalm means to you may well be a marker of your maturity.

Just consider how much of Hebrews’s extensive teaching on Jesus’s heavenly priesthood is derived from Psalm 110:4’s linking Jesus to Melchizedek—the only Old Testament passage to do so. Indeed, it appears that Psalm 110:4 is the “solid food” the writer refers to in Hebrews 5:13–14, which he starts to expound (Heb. 5:9–10), pauses from to rebuke them (Heb. 5:11–14), and then returns to in Hebrews 6:20. In short, how much this psalm means to you may well be a marker of your maturity.

Let us not allow such a feast go to waste. Rather, let us taste and see that the Lord is good.

Are You a Frustrated, Weary Pastor?

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

Being a pastor is hard. Whether it’s relational difficulties in the congregation, growing opposition toward the church as an institution, or just the struggle to continue in ministry with joy and faithfulness, the pressure on leaders can be truly overwhelming. It’s no surprise pastors are burned out, tempted to give up, or thinking they’re going crazy.

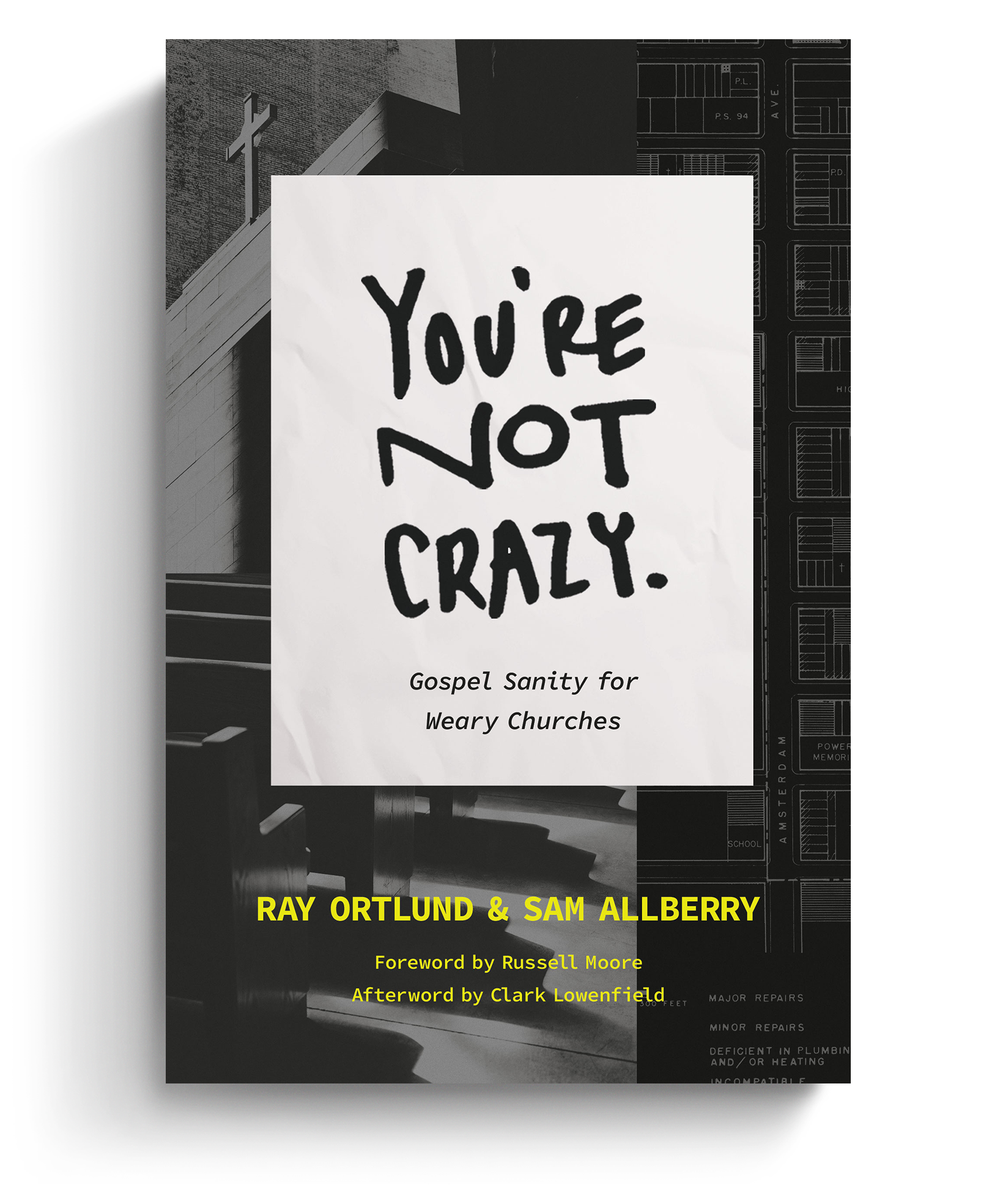

In ‘You’re Not Crazy: Gospel Sanity for Weary Churches,’ seasoned pastors Ray Ortlund and Sam Allberry help weary leaders renew their love for ministry by equipping them to build a gospel-centered culture into every aspect of their churches.

We’re delighted to offer this ebook to you for FREE today. Click on this link to get instant access to a resource that will help you cultivate a healthier gospel culture in your church and in yourself.