The traditional date for Ben Franklin’s famous electrical experiment with his kite is June 10, 1752. It is such a paradigmatic moment in science that there has been a lively debate about the actual date it transpired, or whether it happened at all!

Whatever the actual date of the experiment, it resulted from Franklin’s fascination with electricity and lightning. Franklin suspected the two were equivalent, but no one had proven this. So one stormy day in Philadelphia, Franklin and his son William, who was in his early 20s, sent a kite into the air. As it drew close to a dark cloud, the kite string became electrified. When Franklin put his knuckle close to a key that he had attached to the string, he drew off sparks.

The moment was among the most famous in the history of American science. Thankfully, Franklin survived, as it was foolishly dangerous. A German scientist who tried to recreate Franklin’s experiment a year later was electrocuted and died.

Franklin’s electrical discoveries led him to unprecedented heights of fame for an American. London’s Royal Society awarded him its Copley Medal, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize at the time. The University of St. Andrews in Scotland gave him an honorary doctorate, after which many people called him “Doctor Franklin.”

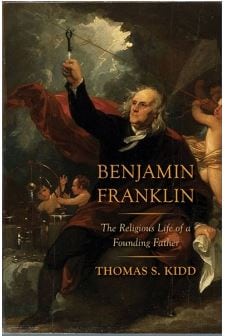

In the course of my research for my religious biography of Franklin for Yale University Press, I realized that Franklin’s kite had unexpected religious significance. Some traditionalist Christians wondered about the propriety of studying and harnessing lightning. (Franklin also developed lightning rods, to help prevent buildings from burning due to lightning strikes.)

Lightning, in the early American world, seemed like one of the most obvious ways that God intervened to show his displeasure. (We still sometimes speak of the threat of people getting “blue bolted” for disrespectful talk or behavior.) Great Awakening evangelist Gilbert Tennent, who had been struck by lightning himself in 1745, called lightning the “awful artillery of heaven.” Some critics of Franklin warned that, however far science progressed, God would still deal out judgment however and whenever he wished.

Harvard professor John Winthrop (the great-great grandson of the Massachusetts founder) scoffed at the critics, arguing that lightning strikes were just part of the natural world. “To have recourse to miraculous interpositions of the ‘Divine Direction,’” Winthrop warned, “is to put an entire end at once to all reasonings about electricity, or earthquakes, or any other natural phenomena.” The more you studied nature, the less fearsome or providential it seemed.

A young John Adams agreed, writing in a personal copy of one of Winthrop’s lectures that criticisms of Franklin’s lightning rod were rooted in “superstitions, affectations of piety, and jealousy of new inventions.”

I suspect that most Christians would agree that more understanding of the natural world—including lightning—is a good thing. But it does raise questions about the secularization of our world. Even many of the most devout Christians in America today have a profoundly naturalistic understanding of their everyday lives. The world of the Puritans (that of Franklin’s parents), and other early Americans, was one of divine wonders and judgments.

Scientific progress has brought innumerable blessings, not least in fields like medicine. But developments associated with the “Enlightenment” also made it more difficult to see much in our world through a providentialist framework. We simply don’t attribute much that happens around us to the hand of God anymore. Those Christians who do (“the Lord opened up a front parking place for me!”) risk eye-rolling even from fellow believers.

For pastors and other Christian leaders, I would simply recommend being attentive to how science like Franklin’s kite experiment has de-mystified our world over the past 264 years or so. Yes, there are risks of trivializing God’s meticulous Providence. Yet we still believe that in his sovereignty, God ordains, controls, and sustains all things according to his purposes. We may not understand the reasons for all those things. But even as we live in Franklin’s naturalized world, Christians must continue to embrace a biblical view of God’s providential rule over our lives.

Sign up for the Thomas S. Kidd newsletter. It delivers weekly unique content only to subscribers.