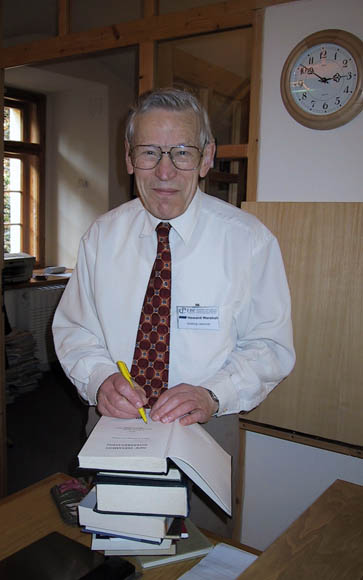

I received word this morning that I. Howard Marshall, professor emeritus professor of New Testament at the University of Aberdeen, had passed away, a month before his 82nd birthday. He had been admitted to the hospital earlier this week and was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Marshall was quite a man, who will continue to have a great impact not only through his voluminous writings but through the quiet, steady, humble, faithful way he lived and mentored. I’m among many who give thanks to God for the privilege of knowing and studying with Marshall. He will be dearly missed, even as his influence continues.

First-Rate Scholar

Many saw Marshall as the “dean of New Testament evangelical interpretation,” the heir of his mentor F. F. Bruce. With his prodigious writing—at least 38 books (authored and edited) and more than 120 essays and articles—Marshall had a significant influence both on biblical scholarship and the church (see bibliography here). In addition to his writing he served widely in fellowships and societies fostering evangelical scholarship.

He taught New Testament at the University of Aberdeen since 1964. Because of Marshall, Aberdeen was for decades a primary destination for postgraduate study for evangelical students from around the world. Among Marshall’s students are many of the leading evangelical New Testament scholars today as well as many lesser-known people who play key roles in majority world churches and schools. As postgrads in Aberdeen, we used to joke that only the oil companies rivaled Marshall for bringing the most internationals to Aberdeen.

Marshall’s words concerning F. F. Bruce can be aptly used of him as well:

[He] will obviously be remembered first of all for his highly distinguished academic career as a university teacher and a prolific writer who did more than anybody else in this century to develop and encourage conservative evangelical scholarship. Possessed of outstanding intellectual ability, a phenomenal memory, and encyclopedic knowledge, a colossal capacity for work, and a limpid style, he produced a remarkable output of books and essays which will continue to be read for years to come, and he trained directly or indirectly many younger scholars now working in all parts of the world. [1]

Forerunner

Marshall produced first-rate technical scholarship that gained the respect of more critical scholars, even when they disagreed. He also wrote for pastors and lay people. Marshall was not among those who disparage popular writing as something beneath a true scholar. Rather, he stated,

it seems to me that those of us who are Christians studying the Bible have a very strong responsibility towards the church to produce what will be helpful particularly to preachers, and also to the church generally. [2]

He once cited the words of David Hubbard as stating his own convictions:

We are not scholars who happen to be disciples, we are disciples who happen to be scholars. [3]

It’s difficult for some younger scholars to comprehend the state of evangelical academic work 40 or 50 years ago. Many of us have grown up accustomed to conservative evangelical seminaries and publishing houses as well as a steady stream of evangelical publications and well-established, prominent evangelical scholars. However, this is a relatively recent phenomenon, a benefit bequeathed to us by those who have gone before us, including Marshall. Marshall had been a key leader in demonstrating how faith and scholarship coincide by both defending biblical truths from critical attack and demonstrating the value of academic rigor to conservative believers.

In articles and books Marshall has helped believers articulate the biblical grounds for their faith, looking for unity but being clear about where dividing lines occur. His convictions are clear in this excerpt from an article supporting young Christians who encounter liberal pastors:

[W]here criticism takes place on the basis of anti-supernaturalist presuppositions and the teaching of scripture is assessed in terms of what modern, unbelieving western man is prepared to accept, again the evangelical will have no truck with it. The kind of ecumenism which tries to assure us that really we all believe the same things will not cut much ice here with evangelicals, for they know that without a clear acceptance of the supreme authority of scripture the gospel which they treasure is liable to be tossed to and fro and carried about by every wind of human teaching. [5]

Young evangelical friends, if you are unfamiliar with Marshall, know that we are indebted to him for helping carve out the space evangelical scholarship enjoys today.

Churchman with an Evangelistic Impulse

To say that Marshall defended is not to say he was defensive. Marshall’s approach was always gracious and winsome, exemplifying the goal not so much of defeating an opponent as winning him to truth. I was with him at a meeting when he had a casual conversation with a scholar friend who had departed from the faith. As we walked away, Marshall said quietly to me, “We must continue to pray that he return to the faith.” This evangelistic impulse lay at the heart of who he was and what he did. His Christmas letter last year opened by telling about the small Bible study group he led and how a young man had recently come to faith in their study.

Our conversations at the Society of Biblical Literature typically centered on the health of the churches in Aberdeen and kingdom advance in the area. Everywhere I went among the churches in Scotland, Marshall was esteemed because of how he helped them understand the Bible through his writings and by preaching in those churches. It’s a key delight of mine, not only to have heard him lecture but to have heard him preach evangelistically.

The gospel was not for him merely an interesting topic of investigation but the central truth from God which reconciles men to God and thus needs to be proclaimed to all people.

Humility

Space fails me to comment on Marshall’s wit, his gracious investment in others, and his cooking skills. I will close by mentioning the thing that struck me most about him—his deep, genuine humility. I was inspired by his knowledge, pushed by his work ethic, encouraged by his friendliness and hospitality, but I was deeply challenged and convicted by his humility.

More than once in conversation I was amazed at his genuine lack of awareness of who he “was” in the eyes of others. To hear him express admiration of the abilities of others you would have thought he had none himself. Once in a conversation in our home, Marshall lamented, “I have never been that good with languages.” This was no coy, back-handed pursuit of a compliment. It was uttered in complete sincerity and even for a moment took me in. Then, I recovered myself and began to ask him about his listening to lectures in German, how he read French items I could not understand, and his well-known acquaintance with Greek and Latin. All this was true. He just did not consider that as being good with languages.

This trait was exemplified at Marshall’s retirement when he was asked to preach in the university chapel on the day of the retirement activities. Marshall continued to serve at the university, but the rules required retirement from his regular post at age 65, and thus he had already moved from his office to a smaller one. As he ascended the pulpit in the chapel at Old King’s College, where years before John Wesley had preached on his visit to Aberdeen, I wondered what his text would be. Without fanfare, he declared his text and read John 3:25–30, which concludes with these words:

He must increase, but I must decrease. (Jn. 3:3)

Howard Marshall lived that text and has now entered into the presence of the Master he sought to exalt.

[1] I. Howard Marshall, “Editorial: Professor F. F. Bruce,” Evangelical Quarterly 62, no. 4 (Oct. 1990): 291.

[2] Carl Trueman, “Interview With Professor Howard Marshall,” Themelios 26, no. 1 (Autumn 2000), 49.

[3] Trueman, “Interview With Professor Howard Marshall,” 48.

[4] R. T. France, “Profile: Howard Marshall,” Epworth Review 29, no. 4 (Oct. 2002), 15-21 [16].

[5] I. Howard Marshall, “The Young Christian and the ‘Liberal’ Pastor,” Expository Times 95 (1984): 364–67 [367].

Free Book by TGC: ‘Before You Lose Your Faith’

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

Many young people are walking away from Christianity—for reasons ranging from the church’s stance on sexual morality, to its approach to science and the Bible, to its perceived silence on racial justice.

TGC’s book Before You Lose Your Faith: Deconstructing Doubt in the Church is an infusion of hope, clarity, and wisdom in an age of mounting cynicism toward Christianity.

For anyone entering college or the workplace and looking for a timely reminder of why Christianity is good news in a skeptical age, make sure to get your FREE ebook Before You Lose Your Faith today!